The document discusses the key principles of motivation in organizational behavior, emphasizing the role of both individual and situational factors. It distinguishes between content theories (which focus on individual needs) and process theories (which explain how those needs influence motivation), and it explores various motivational frameworks, including Maslow's hierarchy of needs and McClelland's acquired needs theory. Additionally, the text highlights the impact of pay transparency on employee motivation and engagement, citing examples and case studies to illustrate these concepts.

![place the way Fields described it, despite the eyewitness

account and Lewandowski’s

admission that he had grabbed her. The editor then instructed

Breitbart staffers “not to

publicly defend their colleague,” according to The Washington

Post. Fields felt betrayed.

This created dissonance between her positive views of the

organization and the lack of

support she received from management. She told a Post

reporter, “I don’t think they

[management] took my side. They were protecting Trump more

than me.”41 She resigned,

as did her managing editor in support of Fields.

Psychologist J. Stacy Adams pioneered the use of equity theory

in the workplace. Let

us begin by discussing his ideas and their current application.

We then discuss the exten-

sion of equity theory into justice theory and conclude by

discussing how to motivate

employees with both these tools.

The Elements of Equity Theory: Comparing My Outputs and

Inputs with

Those of Others The key elements of equity theory are outputs,

inputs, and a com-

parison of the ratio of outputs to inputs (see Figure 5.6).

•Outputs—“What do I perceive that I’m getting out of my job?”

Organizations

provide a variety of outcomes for our work, including

pay/bonuses, medical

benefits, challenging assignments, job security, promotions,

status symbols,

FIGURE 5.6 ELEMENTS OF EQUITY THEORY](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/figure5-220921014320-a15afa9b/85/FIGURE-5-1-ORGANIZING-FRAMEWORK-FOR-UNDERSTANDING-AND-APPLYING-36-320.jpg)

![reading the text.

3. Identify how you will assess your progress in completing the

tasks or activities in

your action plan.

4. Now work the plan, and get ready for success.

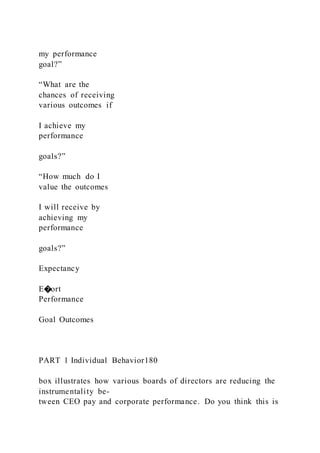

185Foundations of Employee Motivation CHAPTER 5

M A J O R Q U E S T I O N

How are top-down approaches, bottom-up approaches, and

“idiosyncratic deals” similar and different?

T H E B I G G E R P I C T U R E

Job design focuses on motivating employees by considering the

situation factors within the

Organizing Framework for Understanding and Applying OB.

Objectively, the goal of job de-

sign is to structure jobs and the tasks needed to complete them

in a way that creates intrinsic

motivation. We’ll look at how potential motivation varies

depending on who designs the job:

management, you, or you in negotiation with management.

5.4 MOTIVATING EMPLOYEES THROUGH JOB DESIGN

“Ten hours [a day] is a long time just doing this. . . . I’ve had](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/figure5-220921014320-a15afa9b/85/FIGURE-5-1-ORGANIZING-FRAMEWORK-FOR-UNDERSTANDING-AND-APPLYING-67-320.jpg)

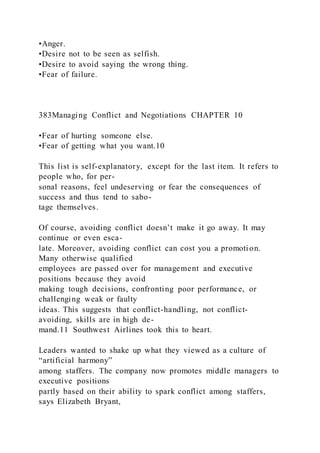

![swap program in

2001. Her reason? “We wanted to give everybody a hands-on

view of each oth-

ers’ job duties, [so they could gain] a greater appreciation and

understanding of

each team member. We also wanted to strengthen our customer

service and take

[our company] to the next level of excellence,” she said.

All Lodwick’s employees ultimately swap jobs for up to 40

hours per year. A

typical swap lasts four hours, and employees are encouraged to

swap with people

across all company departments. The company attempts to make

the process

meaningful and practical by having employees complete a short

questionnaire

after each swap. Sample questions include: “What did you

learn/observe today?

What suggestions do you have for the process you observed?”

Lodwick noted that the program led to increased productivity,

teamwork, and

customer service. It also was a prime contributor to the

company’s receipt of sev-

eral business awards.82

YOUR THOUGHTS?

1. What are the pros and cons of job swaps?

2. What would be your ideal job swap?

3. If you managed a business, how would you feel about this

option for your

employees?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/figure5-220921014320-a15afa9b/85/FIGURE-5-1-ORGANIZING-FRAMEWORK-FOR-UNDERSTANDING-AND-APPLYING-76-320.jpg)

![computer mouse. He looks very focused on

the task at hand. It may be that job crafting is

partly behind his engagement. The company

is using job crafting to increase employee

engagement and job satisfaction. As part

of this effort the company created a

90-minute workshop to help employees

learn how to align their strengths and

interests with tasks contained in their jobs.

© epa european pressphoto agency b.v./Alamy

191Foundations of Employee Motivation CHAPTER 5

perceive their jobs. It should also result in more positive

attitudes about the job, which is

expected to increase employee motivation, engagement, and

performance. Preliminary

research supports this proposition.91

Computer accessories maker Logitech Inc. successfully

implemented a job crafting

pilot program. Jessica Amortegui, senior director of learning

and development, said,

“The company hopes helping employees find more intrinsic

motivation in their work will

be a powerful hiring draw. Logitech plans to begin using the

[program] with all 3,000 of

its workers.”92

Given that job crafting can lead to higher levels of engagement

and satisfaction, you

may be interested in understanding how you can apply the

technique to a former, current,

or future job. The Self-Assessment 5.3 explores the extent to](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/figure5-220921014320-a15afa9b/85/FIGURE-5-1-ORGANIZING-FRAMEWORK-FOR-UNDERSTANDING-AND-APPLYING-82-320.jpg)

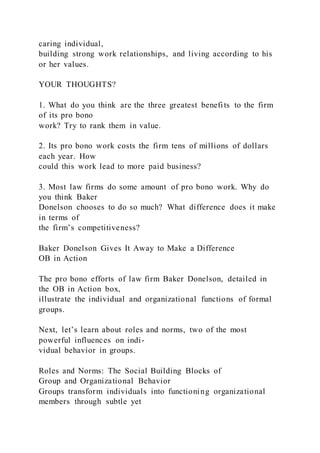

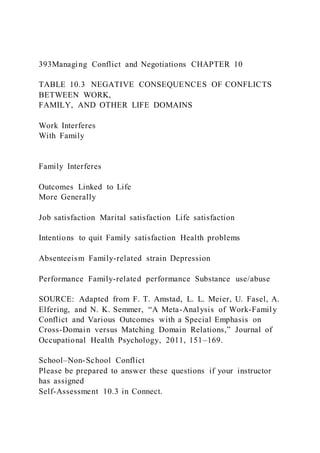

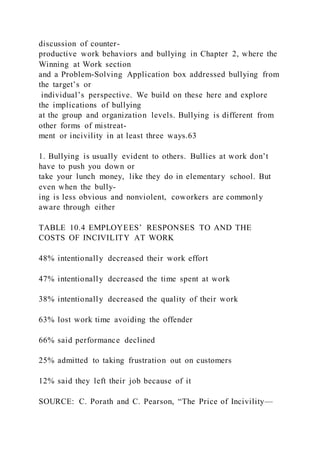

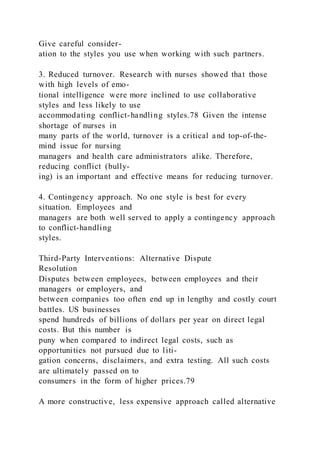

![Drawing from the field of sociology, we define a group as (1)

two or more freely

interacting individuals who (2) share norms and (3) goals and

(4) have a common

identity. These criteria are illustrated in Figure 8.2. Think of

the various groups to which

you belong. Does each group satisfy the four criteria in our

definition?

A group is different from a crowd or organization. Here is how

organizational

psychologist E. H. Schein helps make the distinctions clear:

The size of a group is . . . limited by the possibilities of mutual

interaction and mutual

awareness. Mere aggregates of people do not fit this definition

[of a group] because

they do not interact and do not perceive themselves to be a

group even if they are

aware of each other as, for instance, a crowd on a street corner

watching some

event. A total department, a union, or a whole organization

would not be a group in

spite of thinking of themselves as “we,” because they generally

do not all interact

and are not all aware of each other. However, work teams,

committees, subparts of

departments, cliques, and various other informal associations

among organizational

members would fit this definition of a group.3

The size of a group is thus limited by the potential for mutual

interaction and mutual

awareness.4 People form groups for many reasons. Most

fundamental is that groups usu-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/figure5-220921014320-a15afa9b/85/FIGURE-5-1-ORGANIZING-FRAMEWORK-FOR-UNDERSTANDING-AND-APPLYING-112-320.jpg)

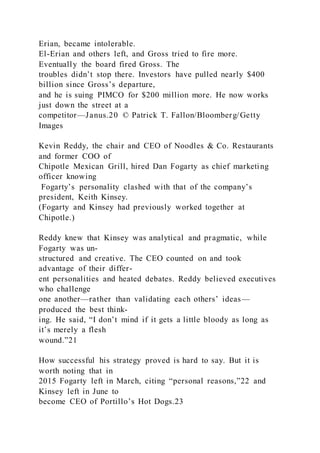

![this as an opportunity for team building (suggestion 5).

4. Identify and focus on the upside (suggestion 6), because it

will help

motivate you to follow the other suggestions and prevent you

from getting

discouraged.

385Managing Conflict and Negotiations CHAPTER 10

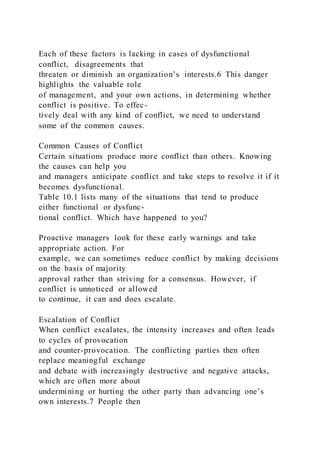

As we discussed in the first section, opposition isn’t necessarily

a problem. It can be a

constructive way of challenging the status quo and improving

behaviors, processes,

and outcomes. New ideas by definition contrast with old ideas

or ways of doing things.

However, opposition becomes an issue if it turns into

dysfunctional conflict and im-

pedes progress and performance. Personality conflict and

intergroup conflict can both

cause a number of undesirable outcomes across levels of the

Organizing Framework

for OB.

Personality Conflicts

Given the many possible combinations of personality traits, it is

clear why personality

conflicts are inevitable. How many times have you said or

heard, “I just don’t like him [or

her]. We don’t get along.” One of the many reasons for these

feelings and statements is

personality conflicts. We define a personality conflict as

interpersonal opposition

based on personal dislike or disagreement. Like other conflicts,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/figure5-220921014320-a15afa9b/85/FIGURE-5-1-ORGANIZING-FRAMEWORK-FOR-UNDERSTANDING-AND-APPLYING-234-320.jpg)

![justify our reasoning to

others, which is a sign that common sense lacks objectivity.

In BusinessNewsDaily, Microsoft researcher Duncan Watts says

we love common sense

because we prefer narrative: “You have a story that sounds right

and there’s nothing to

8 PART 1 Individual Behavior

contradict it.” Watts contrasts a more effective, scientific

approach in his book Everything

Is Obvious Once You Know the Answer: How Common Sense

Fails Us. “The difference

[in a scientific approach] is we test the stories and modify them

when they don’t work,”

hesays.“Storytellingisausefulstartingpoint.Therealquestioniswha

twedonext.”10

OB is a scientific means for overcoming the limits and

weaknesses of common sense.

The contingency approach in OB means you don’t settle for

options based simply on ex-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/figure5-220921014320-a15afa9b/85/FIGURE-5-1-ORGANIZING-FRAMEWORK-FOR-UNDERSTANDING-AND-APPLYING-353-320.jpg)