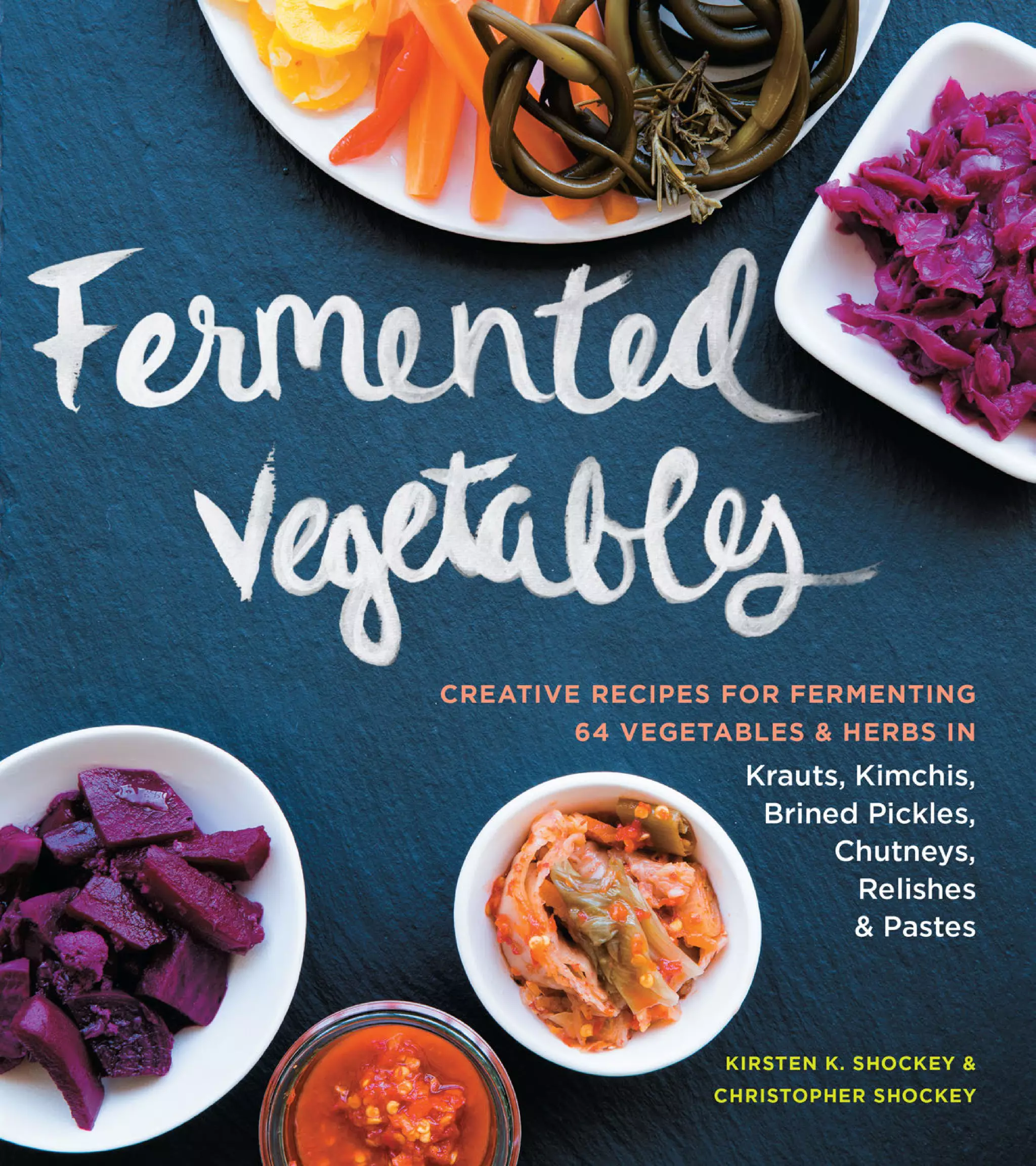

This document provides an introduction and overview of the book Fermented Vegetables by Kirsten K. Shockey and Christopher Shockey. It discusses the authors' journey with fermentation which began in 1999 and evolved into a small commercial fermentation business on their farm in southern Oregon from 2009 to 2011. They realized they were more passionate about the artistry and experimentation of fermentation rather than the commercial and profit-driven aspects, so decided to write this book to share their knowledge and help others answer common questions about fermenting vegetables.

![So You Want to Ferment without Salt?

Any serious fermentista will encounter salt-phobic people who try to make salt-free sauerkraut or want

to convince you to do the same. There are certainly a lot of recipes out there on the Web; some require

a blender, some use seaweed or celery seeds in place of salt. With care and luck, fermentation can be

accomplished without the salt, and some people do so successfully. Expect these ferments to be softer and

at times mushy.

But why not use salt in your ferments? Our bodies need salt anyway. Without it we die. A study pub-

lished in the American Journal of Medicine in 2006 reads, “Sodium intake of less than 2300 mg [the daily

recommended allowance] was associated with a 37% increase in cardiovascular disease mortality and a

28% increase of all-cause mortality.” In other words, without the correct balance of salt and water, the

systems in our body stop functioning. As with most things, common sense and balance are key.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/fermentedvegetablesrecipes-230626161132-9031b5fb/85/Fermented-Vegetables-Recipes-pdf-27-320.jpg)