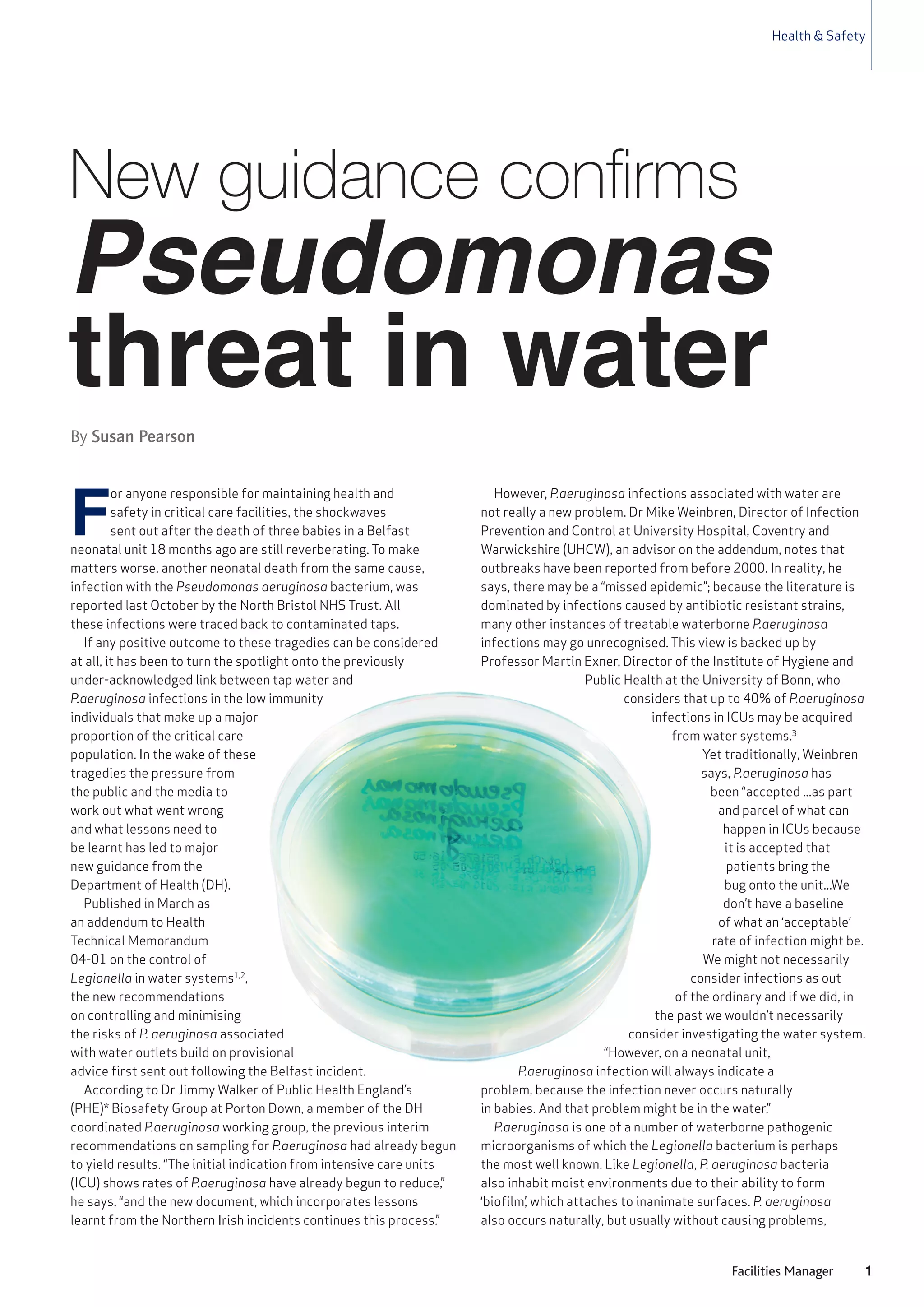

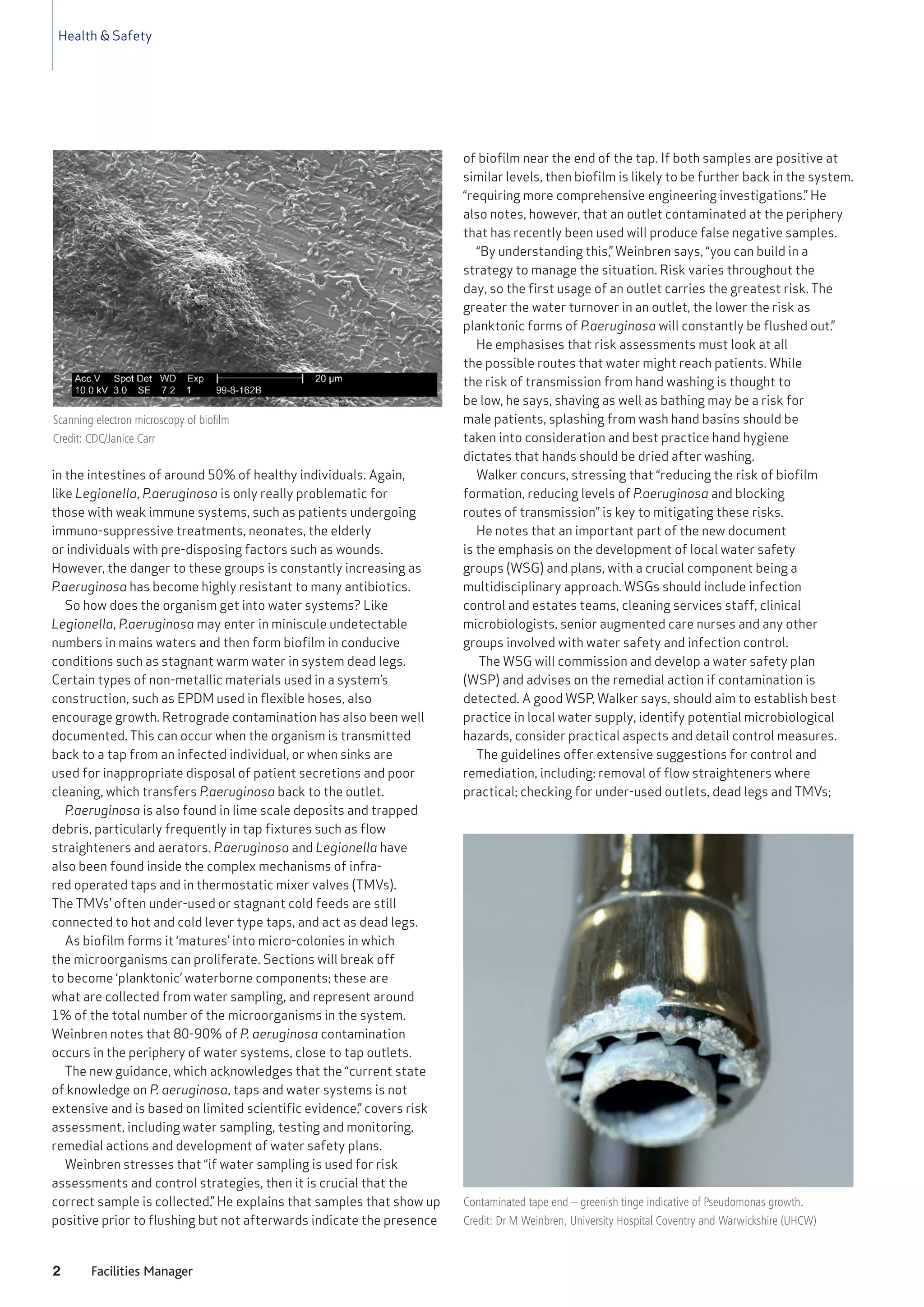

This document discusses new guidance from the Department of Health on controlling and minimizing risks from Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteria in water systems, particularly in critical care facilities. The guidance was prompted by neonatal deaths from P. aeruginosa infections traced to contaminated taps. The guidance emphasizes risk assessment, water sampling, remedial actions, and developing water safety plans and groups with multidisciplinary teams. Key recommendations include removing unnecessary fixtures, checking for stagnant areas, regular maintenance, and preventing retrograde contamination. Controlling biofilm formation and transmission routes is seen as key to mitigating risks from this opportunistic waterborne pathogen.