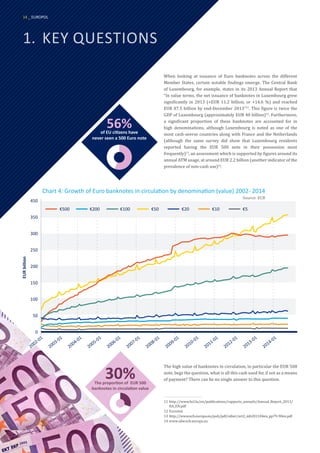

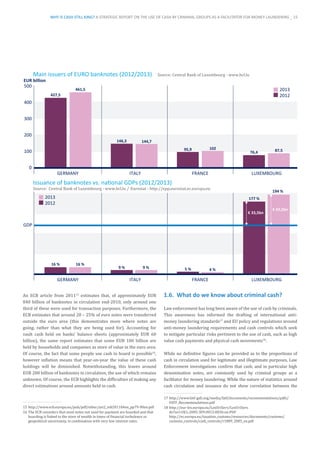

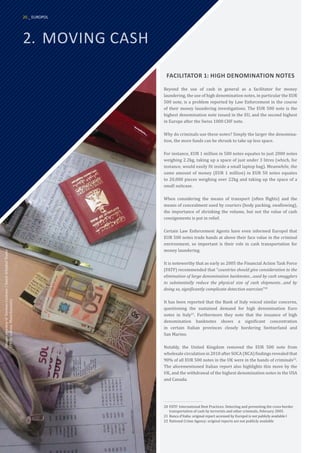

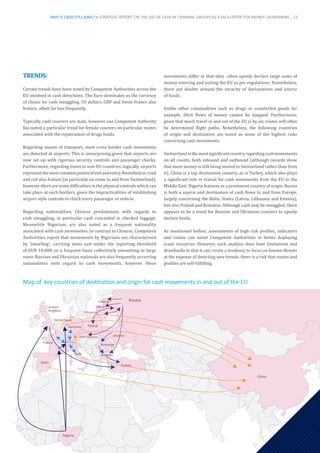

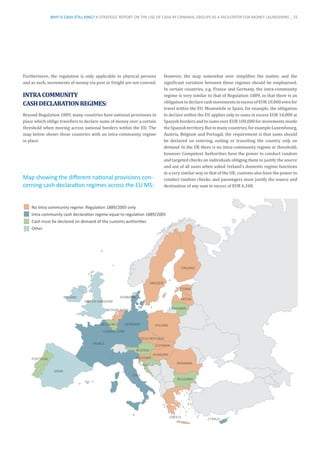

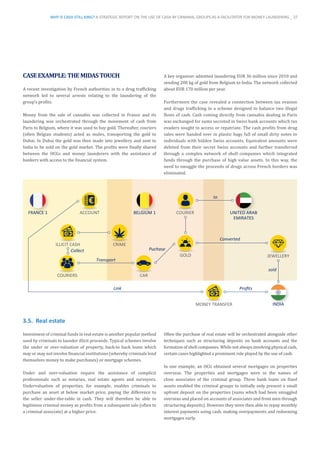

This document summarizes key questions around the use of cash, particularly by criminal groups for money laundering purposes. While cash usage is declining slightly for regular payments, the total value of euro banknotes in circulation continues to rise beyond inflation levels. A significant proportion of cash in circulation, including high denomination notes, is not used for payments and its purpose is unknown. Law enforcement investigations still find that cash remains the primary method for placing, layering and integrating illegal profits. Criminals use cash to facilitate money laundering as it allows them to conceal profits and maintain control over funds in an anonymous manner.