Endangered Species in NJ Face Habitat Loss and Other Threats

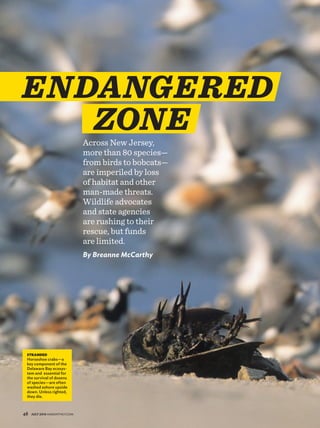

- 1. PHOTOGRAPHS:(SUBJECT)NAMEHERE;(SUBJECT)NAMEHERE Across New Jersey, more than 80 species— from birds to bobcats— are imperiled by loss of habitat and other man-made threats. Wildlife advocates and state agencies are rushing to their rescue, but funds are limited. By Breanne McCarthy 48 JULY 2016 NJMONTHLY.COM STRANDED Horseshoe crabs—a key component of the Delaware Bay ecosys- tem and essential for the survival of dozens of species—are often washed ashore upside down. Unless righted, they die. ENDANGERED ZONE

- 2. PHOTOGRAPHS:(SUBJECT)NAMEHERE;(SUBJECT)NAMEHERE Photographs by STEVE GREER Illustrations by JANICE BELOVE JULY 2016 NEW JERSEY MONTHLY 49 pity the poor horseshoe crabs. Despite 450 million years of evolution, the marine arthropods have never developed a foolproof way to flip themselves over when they’ve been turned upside down on a sandy beach. That leaves them vulnerable to sun ex- posure and birds of prey. To assist the prehistoric creatures, who en- ter New Jersey bay beaches to mate and lay their eggs each spring, the Wetlands Insti- tute helped launch reTURN the Favor. In late April, Lisa Ferguson, director of research and conservation with the Stone Harbor-based nonprofit, carefully explained to a group of first-time volunteers the proper technique for turning the crabs right side up. Throughout the spring and early summer, the volunteers and dozens of others probed miles of sand along the Dela- ware Bay to aid the crabs,ensuringthat as many as possible survived to spawn millions of eggs. The crabs are not the onlybeneficiariesoftheprogram. Their eggs support dozens of species and are essential for the survival of one in particular: the rufa red knot, one of more than 80 species listed as endangered or threatened in New Jersey. The rufa red knot, a medium-sized shore- bird, embarks each year on one of nature’s longest migrations. For some of the birds, the annual journey stretches an astounding 18,000-mile round-trip between their breed- ing grounds in the Canadian Arctic to their wintering quarters in Tierra del Fuego, at the southernmost tip of South America. When the birds head north, they follow a path along the Atlantic Flyway, with a cru- cial stop on the Delaware Bay, halfway to their destination. Some of the birds will have flown nonstopforsixdaystofeedonthebay’sfat-rich horseshoe crab eggs. The knots arrive at the bay weighing about 120 grams (just over 4 ounces). “They come completelydepleted,”saysStephanieFeigin,a biologist with the Conserve Wildlife Founda- tionofNewJersey(CWF).“Theyactuallystart digesting their own intestinal tract.” Some birds rest for two days before they can even begin eating. Once they start feasting on crab eggs, they refuel in a frenzy for about two weeks. Theymuststoreenough fat to reach their average normal weight of 180 grams (about 6 ounces) before taking off— thousands at once—for the Arctic. In a ritual of nature that has taken place for morethan10,000years,thespawningofhorse- shoecrabeggsinearlyMayissoonfollowedby the arrival of the knots. The dance in the bay had unfolded in perfect balance for centuries. Then, in the 1990s, the red knot population began to plummet. The number visiting the Rufa red knot

- 3. JERSEY’S BATS: HANGING ON The invasive fungus Pseu- dogymnoascus destructans is believed to have entered the United States in 2006 after hitching a ride from Europe on the boot of an unsuspecting spelunker (cave explorer). The spelunker inadvertently deposited the fungus in a cave in Albany, New York, where it proliferated in the cold and damp den. While the hibernating bats slept, the fungus crept among them, leaving white markings around their muzzles and eating away at their wings—symptoms in bats affected by white- nose syndrome (WNS), a disease caused by the fungus. “It attacks the wing membrane so they’ll actu- ally have shredded wings,” says Stephanie Feigin, biologist with Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey. “It hurts, so it kind of wakes them up, and that costs them fat reserves and water stores that they worked all spring and summer to build up.” Incapable of flight, the affected mammals sometimes fall to the floor of the cave, where they starve or freeze to death. If they can still fly, they may leave the cave to look for food. Outside, they are ex- posed to cold and struggle to find food to refuel their depleted and dehydrated bodies. Since the initial outbreak, the fungus has radiated across the east- ern United States, north to Canada and southwest to Mississippi, killing more than an estimated 6 mil- lion bats. The fungus ar- rived in New Jersey caves in 2009. Among the state’s affected species: the northern long-eared bat, which was listed as endan- gered last year. Once so abundant its population was not tracked here, it is Delaware Bay decreased from 90,000 in 1980 to about 50,000 in 1998. The follow- ing year, the rufa red knot was added to the state’s threatened-species list. Yet the threatcontinued.By2007,therufaredknot reached a nadir of 13,000. Biologists scrambled to explain the de- cline. It wasn’t long before they realized the crisis was tied to the overharvesting of horseshoe crabs. Beginning more than a century ago, crabs had been taken by the millions to be ground up and used as fertilizer. That use slowed, but was re- placed by another threat in the mid-20th century, when the eel-and conch-fishing industries began using the crabs as bait. Then in the 1970s, the discovery of the compound limulus amebocyte lysate (LAL) in crab blood, led to harvesting by the biomedical industry, which markets the compound to test injectable drugs and implantable medical devices for biological contamination. Over the past four decades, the bleeding of crabs for LAL has become a multimillion dollar industry; hundreds of thousands of crabs continue to be captured each year on the Atlantic shores as raw material. After conservationists fought for half a decade, a moratorium was placed on crab harvesting in 2008, limiting the number that can be taken from the bay. Currently, no crabs can be harvested for bait in New Jersey, but an unspecified number can still be taken for biomedi- cal use. (About 500,000 crabs were harvested at biomedical facilities from Maine to Florida in 2014, according to the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission.) Despite the moratorium, red knot numbers remained low and the species was recategorized from threatened to endangered in 2012. Such designations are determined on a state level by the New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife Endangered and Nongame Species Program (ENSP), and on a federal level by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service or the National Marine Fisheries Service. Horseshoe crabs are not currently listed, but some reports estimate the Delaware Bay population, while still numbering in the millions, has declined; one study shows a 90 per- cent decline from 1990 to 2005. That’s why it’s so important for scientists and volunteers to do everything they can to help both species until they begin to rebound—even if it entails something as unscientific as walking the beach in search of overturned crabs. The efforts have helped stabilize the red knot population, but the birds are still at only 26 percent of their historic numbers. The overharvesting of crabs is not their only problem, says ENSP chief Dave Jenkins. Threats to the bird include habitat loss due to sea level rise; coastal development; shoreline obstructions like seawalls and jetties; intensified competi- Northern long-eared bat 50 JULY 2016 NJMONTHLY.COM Timber rattlesnake SPRINGFLING Horseshoe crabs pile up on the Dela- ware Bay beaches in New Jersey to breed each spring.

- 4. tion with other species for food; distur- bances by vehicles, people, dogs, aircraft and boats; and climate change. The red knot is a prime example of what an endangered species looks like. According to the ENSP website, an endangered species is one “whose prospects for survival in New Jersey are in immediate danger due to various threats.” Assistance is needed to help prevent extinction. Threatened species are those that may become endangered if conditions affecting them begin or continue to deteriorate. A third designation—species of special concern, which includes over 100 additional species—indicates popu- lations that warrant special attention because of conditions that may result in their becoming threatened. like the red knot, almost all of New Jersey’s endangered or threatened species face multiple threats. Primary offenders are habitat loss due to destruc- tion of the natural landscape for develop- ment and habitat degradation due to pollution and other stressors on land and waterways. Habitat fragmentation—the separation of habitat into smaller units by roads, development and farming—is another major threat. These primary threats are exacerbated by secondary threats, including disease, human distur- bance, climate change, invasive species and the illegal pet trade. New Jersey’s more than 80 threatened or endangered species come in all shapes and sizes, from the 1.5-inch bronze copper butterfly to the 60,000-pound humpback whale. The very presence of some of Jersey’s estimated to have dropped in number by 99 percent. The little brown bat, averaging 3 inches in length, has also been sig- nificantly affected. Their main hibernacula, located at Hibernia Mine in Morris County, saw a drop from approximately 25,000 bats in 2009 to 462 in 2015. Biologists worldwide— including those in New Jersey—are studying bat species closely. Feigin says it’s unclear if affected spe- cies will be able to survive or how long it might take the bats to recover. “We are seeing it level off a bit,” says Feigin. “We’re not seeing as many dead bats on the floors of hibernias.” However, she adds, “we’re not sure why we’re not seeing an uptick in the numbers, so that kind of raises a number of other questions.” Bats are essential to the food chain in New Jersey. They feed on pests and pollinate vegetation. Because of their roles, they are estimated to be worth billions of dollars to the agricultural industry worldwide. Feigin says humans need not fear bats. The mammals, she says, clean themselves more than an average house cat and rarely carry disease. “Bats are secretive little creatures, and all they do is benefit humans,” she says. “Less than 1 percent of bats have rabies. You’re actually more likely to get hit in the head by a falling coconut than get a disease from a bat.” Feigin says there are ways citizens can go to bat for the bats. do not disturb: Bats in New Jersey roost in abandoned mines, tunnels and caves, as well as in dead and dying trees and buildings. Disturbing bats can cause them to lose fat reserves, especially dur- ing hibernation, or could result in the spread of disease like WNS. hire a professional: Bats sometimes find shelter in homes or com- mercial buildings. Killing or harming a bat is illegal, so evictions should be done by professional bat excluders who follow proper guidelines. A list of companies can be found at conservewildlifenj.org. install a bat house: CWF offers free bat hous- es that can be installed on your property to attract a new or evicted colony. To build your own, contact CWF for blueprints and information. leave dead trees: These trees, known as snags, make great homes for various species including bats, who roost in them during spring and summer. If you have snags on your property, leave some standing as long as they do not pose a threat.—BM ASIMPLEGESTURE Volunteers with re- TURN the Favor visit one of 19 Delaware Bay beaches in New Jersey, where they help stranded horse- shoe crabs by flipping them right side up. JULY 2016 NEW JERSEY MONTHLY 51

- 5. 52 JULY 2016 NJMONTHLY.COM listed species might come as a surprise to most residents. Take the bobcat, the last of New Jersey’s big cats. These wild carnivores suffered at the turn of the 20th century when massive destruction of for- ests for lumber, fuel and charcoal isolated cat populations. Vehicle-caused mortality was another factor in the near extinction of the species in the 1970s. Desperate to keep the cats alive in the Garden State, 24 bobcats from Maine were introduced between 1978 and 1982. While the project appeared successful, the species has been listed as endangered since 1991. Habitat loss and fragmentation and death by auto- mobile continue to take their toll. The shy cats sometimes avoid crossing roadways, further reducing their territory to isolated patches. Scientists are unsure how many remain in the state today. Many amphibian species, like the endangered blue-spotted salamanders of northern New Jersey, are threatened by continued degradation of habitat due to development and decreased water qual- ity. Roads have split and fragmented their range, leaving isolated populations vul- nerable to severe declines and reduced genetic diversity. Some of these amphib- ians, like the Jefferson salamander, a species of special concern, are potentially subject to 100 percent road mortality in certain areas each spring when they try to reach their breeding grounds, says Kelly Triece, wildlife biologist with CWF. The endangered northern long-eared bat, whose population has declined by 99 percent over the past decade, suffered drastically due to the spread of white- nose syndrome (WNS)—a disease caused by an invasive fungus (story, page 50). Invasive species—like the fungus causing WNS or the European starling, an invasive bird introduced to the United States by Shakespeare enthusiasts in the 19th century—can spread disease among native plants and animals and can also outcompete indigenous species for habitat and food. Pollution affects several endangered species, including the Atlantic sturgeon and the bog turtle. Listed species like WAYS TO GET WILD State agencies and conservation groups welcome volunteers to help protect imperiled species. Here are ways to stay informed and get involved: 1 get educated: Each fall, the state Department of Environmental Protection (DEP) holds its annual New Jersey WILD Outdoor Expo to connect state residents with the natural world through outdoor activities, hands-on education and the latest conservation information. Other pro- grams and events—including guided nature walks, campfire talks and even nature-infused yoga lessons—are led by the DEP and conservation groups and take place year-round. 2 get connected: Conserve Wildlife Foundation (CWF) of New Jersey is one of several conserva- tion groups with live webcams offering a birds-eye view of wildlife like ospreys, falcons, bald eagles and bats. The Creature Show is a docu-web series at creatureshow.com cre- ated by award-winning documentary filmmaker Jared Flesher, a native New Jerseyan. The series is dedicated to conservation storytelling with a focus on Garden State animals and habitats. 3 report sightings: Biologists from the New Jersey Endangered and Nongame Species Program (ENSP) use data from the public to help determine population and identify the crucial habitat of imperiled spe- cies. Data can be reported to the ENSP website. 4 support native biodiversity: This means planting native species and avoiding invasive plant species—some of which can still be found at garden centers. A complete list of invasive species to be avoided can be found on the New Jersey Invasive Species Strike Team website, njisst.org. 5 give back: Support conservation efforts with fi- nancial donations such as buying a Conserve Wildlife license plate, which helps fund the ENSP. You can also symbolically adopt a rare species through CWF.—BM the bog turtle and timber rattlesnake, are also decreasing in the wild in part because of their value in the pet trade. Native species that are thriving can also do damage to listed species. Preda- tor species like red fox and raccoons that thrive around human populations are threats to vulnerable species like the endangered piping plover and other beach-nesting shore birds. “Red foxes are good at getting hand- outs, they’re good at finding food, so their populations are arguably higher than natural levels,” says Jenkins. “So in turn, they prey on piping plovers.” the threats continue to mount, but funding for the state agencies responsible for protecting vulnerable wildlife is limited. The ENSP—the state program charged with protecting New Jersey’s endangered and threatened wildlife under the New Jersey Endan- gered and Nongame Species Conserva- tion Act (ENSCA) of 1973—has a budget of just $2.5 million to cover its 14-person staff and all its projects. ENSP must pro- tect and manage the state’s nearly 500 wildlife species—including those that are endangered or threatened. The funds are cobbled together mainly Blue-spotted salamander

- 6. PHOTOGRAPH:(BOBCAT)TYLERCHRISTENSEN;(TUNNEL)JONATHANCARLUCCI from federal aid, including State Wild- life Grants and Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Program funding, along with state appropriations, a state income tax checkoff and revenue from Conserve Wildlife license plates. While they make do, Jenkins estimates the ENSP would need 10 times its budget to fully implement even 80 percent of the projects in its Wildlife Action Plan, a federally mandated outline of the steps needed to conserve wildlife and habitat. Kelly Mooij, vice president of govern- ment relations with conservation group New Jersey Audubon, says when funds are tight, allocation is key. “With the declining revenues com- ing into the state, and all of the other significant and overwhelming financial obligations of the state pensions, with the transportation trust fund, health care, schools—we have to really restructure and reconsider how investment is made,” says Mooij. What’s more, some biologists fear an erosion of public support for conserva- tion, traced in part to increased urbaniza- tion, as well as ongoing financial issues for many state residents. Additionally, today’s environmental issues—such as climate change and pollution—tend to be at once vague and overwhelming. “Environmentalandconservation issuesareoneofthosethingsthatpeople feelstronglyaboutbutareeasilydiverted awayfrombecauseofother[worries],like havingajob,”saysJenkins.“Andthatdis- connectmakesithardertobuildthepoliti- calwillandsupportthatisnecessary.” The ENSP constantly performs spe- cies, status assessments. The next round of updates should be complete by early 2017. Jenkins says the number of endan- gered and threatened species on the list will likely increase. “No one should be surprised that we’re taking more species on than we’re taking off,” Jenkins says. “Some are species that stay in New Jersey and don’t move, so we’re reflecting on what’s happening with them in New Jersey. But with other species, particularly bats or birds, their numbers are declining globally, and we are part of that.” Some experts predict the continuing global extinction of a large number of species. Larry Niles, former chief of the ENSP who currently works on various wildlife projects all over the world and throughout New Jersey, says there are no easy fixes. “It’s worse than anyone can imagine,” says Niles. “What I tell people is you’re wrong if you think biologists [alone] can help you out of this.” The consequences of extinctions Atlantic sturgeon can be dramatic, even hitting the state economically. The annual migrations of shorebirds alone bring in tens of millions of dollars in tourism money to the state, says Mooij. The threat to bats can also have a financial impact. They are one of the best and cheapest forms of pest control. One little brown bat can eat up to 3,000 insects in a single night, including gypsy moths, stink bugs and mosquitoes. Stud- ies have also shown that bats, who act as pollinators, are worth billions of dollars to the agricultural industry worldwide— an industry that happens to be the third largest in the state. The bats’ consumption of mosquitoes potentially depresses the number of mosquito-born illnesses like West Nile virus. With the current focus on Zika virus, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently released maps showing that the two types of mosqui- toes that might carry the disease could be present in New Jersey. Feigin says she’s sure the bats here would be happy Continued on page 216 THEIMPERILED Bobcats sometimes avoid crossing roads, which fracture their habitat. Right: Zoolo- gist Brian Zarate works on connecting habitats for imperiled species with tunnel and fencing projects like this one in Bedminster. JULY 2016 NEW JERSEY MONTHLY 53

- 7. 216 JULY 2016 NJMONTHLY.COM endangered zone PHOTOGRAPH:(TURTLE)BRITTANYDOBRZYNSKI to eat them. Each species—whether predator or prey—has its place in the circle of life re- sulting in biodiversity and balance in the state. “A functioning ecosystem includes all of the parts, and these species are the parts,” Jenkins says. To protect biodiversity while develop- ment continues, Jenkins says his agency is focusing on habitat management and restoration. This is especially important in New Jersey because, while specific landscapes in the state are protected, the habitat of listed species is not directly protected under the state’s ENSCA. “There’s no law that protects an en- dangered species’ habitat,” Niles says. “If it doesn’t fall in a wetlands, if it doesn’t fall in the Pinelands, then there’s no law against destroying [the] habitat.” One of the ENSP’s main projects is to identify areas inhabited by the state’s most imperiled creatures. The Landscape Project, started under Niles in 1994, maps the occurrences and the habitat of these species. Theprojectpullsinformationfroma geographic-informationsystemdatabase calledBiotics,compiledbyCWFbiolo- gists.Theinformationisamixofdata fromENSPsurveys,professionalsurveys andrare-speciessightingreportssubmit- tedbythepublicviatheENSPwebsite. “We encourage people in the general public to submit their observations, be- cause our biologists just can’t be in every corner of the state every day,” says the CWF’s Mike Davenport, who has worked on Biotics for over a decade. “It’s also helpful in private lands that we might not have access to.” The Biotics data, along with land-use information, is used to create Landscape Project maps. The interactive maps, while not law, can be used “for planning purposes before any actions, such as proposed development, resource extrac- tion or conservation measures, occur,” according to the New Jersey Division of Fish and Wildlife website. Landscape Project findings are also used to identify land to protect (and sometimes acquire) through state funding ini- tiatives like Green Acres, which sets aside money for recreation and con- servation needs. Another ENSP initiative, the Con- necting Habitat Across New Jersey (CHANJ) project, aims to preserve and restore valu- able habitat corri- dors through which terrestrial wildlife need to move in order to breed, as well as find food, shelter, water and other resources. Often, these corridors are blocked or interrupted by development or well-traveled vehicular roads. “CHANJ is to identify those areas that we think are the most important to maintain or restore the ability of wildlife to move through the land- scape,” Jenkins says. “We will in some cases have to secure the habitat and buy it, or get landowner easements or agreements. Then it’s restoring… [and] managing the habitat so that it becomes more conducive to wildlife moving through it.” One way the land can be managed is through the installation of wildlife road- crossing structures like tunnels and bridges. A first-of-its-kind tunnel system was installed last summer beneath River Road in Bedminster. The $90,000 initiative—a partnership between the state DEP, the township of Bedminster and New Jersey Audubon—included the installation of wooden fencing spanning 2,000 feet on either side of River Road, which steers wildlife to one of five tun- nels. Built with threatened wood turtles in mind, the tunnels can accommodate small reptiles, amphibians and mammals as large as a fox. Gretchen Fowles, an ENSP biologist and coleader of CHANJ, says alliances make such initiatives possible. “We’ve had partnerships with conservation or- ganizations, the transportation agencies, municipalities—whoever has jurisdic- tion over that roadway—wildlife experts, they all come together to come up with a solution,” says Fowles. New Jersey has about a dozen struc- tures used by wildlife. ENSP zoologist Brian Zarate, a CHANJ coleader, says animals sometimes utilize crossing structures like bridges and footpaths meant for hikers and bikers. Structures designed specifically with wildlife in mind include three Route 78 overpasses built in Somerset and Union counties in the 1970s—the first such project of its kind in the country, says Zarate. Two more tunnel projects are planned, including one for Waterloo Road in Byram Township, a valuable tract of land for amphibians like the Jefferson salamander, a species of special concern. Highly susceptible to road mortality, amphibians, who cross in the thousands during their March migrations, currently have to be helped across the road by biologists and volunteers. “We’ve been working really hard to find funding to get permanent tunnels put under the road,” says Fowles, “so people don’t need to be out there helping to shuttle these animals across.” some forms of habitat enhance- ment and management seem to go against human instinct. The habitat of the golden-winged warbler, whose breed- ing population was recently listed as en- dangered, generally follows the eastern side of the Appalachian Trail in northern New Jersey. The bird needs young forest habitat to thrive, but in New Jersey, our forests are all fairly old. “In New Jersey, all of our forests are 60 to 100 years old because in the 1880s, the forests were destroyed through ag- riculture or for fuel,” Triece says. “Since Continued from page 53 HARDWIRED Biologists affix radio transmitters to endangered bog turtles in southern New Jersey to track their every move.

- 8. JULY 2016 NEW JERSEY MONTHLY 217 then, we’ve started preserving land…but because of that, they’re all the same age.” Triece says young forests occur after natural disturbances like fires or floods. But humans act to stop such natural oc- currences. In this situation, controlled burns or the cutting of trees can be used to create an open canopy—acts that are sometimes deemed controversial, even amongst conservationists. Habitat management and restoration work go hand in hand. Invasive plants like phragmites, reed canary grass and Japanese barberry all commonly take over the wetland habitats of the endan- gered bog turtle. To help the species, biologists attempt to control the invasive plants and reintroduce native flora. Conservation groups and state agen- cies often work together to achieve common goals. New Jersey Audubon, for example, recently helped to pass an amendment to the state Constitution to permanently allocate 4 percent of the state’s corporate business tax—or about $80 million annually—for land preservation and stewardship of open space. However, enabling legisla- tion was vetoed by Governor Chris Christie. It will likely take a future governor to facilitate implementation. Once implemented, “we will have consistent, pay-as- you-go open-space funding so that we can strategically invest in preservation and habitat restoration,” says Mooij. Some of New Jersey Audubon’s biolo- gists recently partnered with the ENSP on a project to track newfound and unrecorded bog turtles living in freshwa- ter wetlands in Salem County. To better understand the endangered species, the biologists affixed radio transmitters to four turtles and so far have found that the turtles reside in small patches of land no bigger than half an acre. Determining which habitat the turtles find favorable will allow the land to be properly man- aged in hopes that the turtle numbers there can increase. New Jersey Audubon biologists also work on shorebird banding alongside ex- ENSP chief Niles, who coleads the Dela- ware Bay Shorebird Project. The goal is to collect data on and track shorebirds like the red knot, ruddy turnstones and semipalmated sandpipers, among others. Niles worked over the past few years to restore vital habitat for red knots and other shorebirds both in the bay and on the Atlantic coast. On the bay, he and his team—in partnership with New Jersey Audubon, the American Littoral Society and CWF—have helped restore the habi- tat of six vital sites stretching over two miles of beach, where the landscape was diminished. Volunteers also help to supplement an array of projects across the state. Triece, of CWF, runs the volun- teer-based Amphibian Crossing Project in North Jersey. Dozens of volun- teers show up on rainy nights in mid to late March to help amphibians cross the road—literally. “In one night, on one transect of road maybe 50 to 100 meters long, we might get 2,000 amphibians,” she says. “So we’ve recruited volunteers to basically walk up and down the road to collect data on the species and the time, and we re- cord temperature and weather so we can quantify what’s going on at that site.” This past spring, on Waterloo Road in Byram Township, site of the proposed crossing tunnel, volunteers assisted the safe crossing of 1,432 amphibians, in- cluding spotted salamanders, which are currently recommended to be listed as a species of special concern. A similar project takes place every summer in South Jersey, where about a dozen volunteers patrol roads to help protect northern diamondback terrapins which are also being considered for the species-of-special-concern list. with so many challenges, environ- mental workers are buoyed by their success stories, such as the comeback of New Jersey’s bald eagle population. The species was down to one nesting pair in the early 1980s, due largely to DDT use; today, thanks to an aggressive protection and reintroduction initiative, the popula- tion is stable, with 161 nesting pairs. The horseshoe crab moratorium is another state conservation win. Hope also exists in a $1.3 billion federally funded conservation plan of- fered by a blue ribbon panel assembled by the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies (AFWA). The panel, made up of politicians, representatives from en- vironmental groups, academic research- ers, business executives and members of the oil industry, has called on Congress to “dedicate up to $1.3 billion annually in existing revenue from the develop- ment of energy and mineral resources on federal lands and waters to the Wildlife Conservation Restoration Program.” Aplanlikethat,Jenkinssays,could meanasmuchas$25million—about10 timestheENSP’scurrentbudget—coming intothestateforconservation. For now, volunteers are doing their part in whatever way they can to support state efforts and conservation groups. Gail Hill of Bucks County, Pennsylva- nia, recruited volunteers and traveled more than two hours to take part in the reTURN the Favor program to rescue horseshoe crabs in the Delaware Bay. Hill, who is director naturalist of the Peace Valley Nature Center in Penn- sylvania, says she enjoys volunteering with conservation projects wherever she can. “Next time we come, we’ll probably bring half the neighbors in the state,” she laughs. “It’s just the coolest thing—we’re really excited about it.” HELPINGHANDS Biologist Kelly Triece runs the Amphibian Cross- ing Project, leading volunteers who help amphibians cross the road. PHOTOGRAPHS:(AMPHIBIANCROSSING)NICOLEGERARD Bobcat