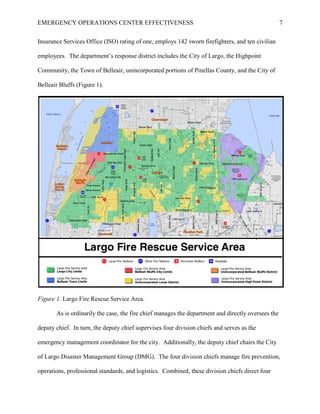

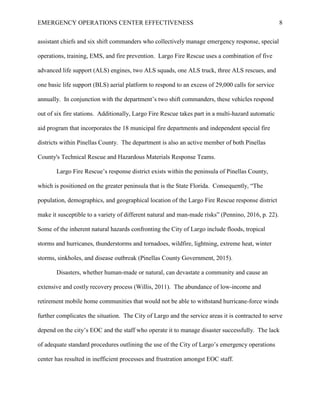

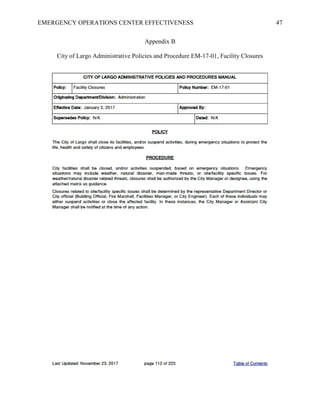

The document discusses the effectiveness of the Emergency Operations Center (EOC) in Largo, Florida, highlighting the need for improved standard procedures for disaster response. It identifies shortcomings in existing EOC operations and draws on industry best practices to recommend enhancements in staffing, policy development, and physical layout of the EOC. The analysis underscores the importance of adequate training and organization for successful disaster management, particularly in the face of increasing environmental risks.