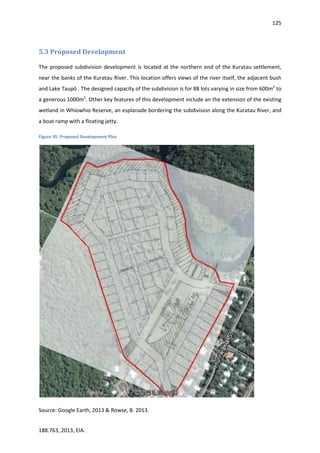

The proposed development faces challenges including development in a significant natural area, liquefaction issues, and high sediment levels in the Kuratau River and its mouth. A full environmental impact assessment is recommended to fully understand and mitigate the potential impacts, which are considered significant. Alternative development options should also be investigated if the current proposal is not approved.

![160

188.763, 2013, EIA.

Gaiser, E., Richards, J., Trxler, J., Jones, R., & Childers, D. (2006). Periphyton responses to

eutrophication in the Florida Everglades: cross-system patterns of structural and

compositional change. Limnology and Oceanography, 51(1), 617-630.

Gisborne District Council. 2009. Proposed regional coastal environment plan.

Glasson, J., Therivel, R., & Chadwick, A. (2005). Introduction to Environmental Impact Assessment.

(3rd

ed.). New York: Routledge.

Goodman, J. (2012). Submission Form [Submission on Proposed Southern Settlements Structure

Plan]. Retrieved from http://www.Taupōdc.govt.nz/our-council/policies- plans-and-

bylaws/structure-plans/southern-settlements-structure-plan/Pages/

southern-settlements-structure-plan.aspx.

Google. (26th

Feb 2013). Google Earth [Program], Version 7.0.3.8542.

Hanna, K. (2005). A brief introduction to environmental impact assessment. In Hanna, K. S.

(ed.). Environmental Impact Assessment: Practice and Participation (3-15). Ontario,

Canada: Oxford University Press.

Hoadley, R. (2013). Comment [Submission on Proposed Southern Settlements Structure Plan].

Retrieved from http://www.Taupōdc.govt.nz/our-council/policies-plans-and-bylaws/

structure-plans/southern-settlements-structure-plan/Pages/southern-settlements-

structure-plan.aspx.

Iannuzzi, T., Weinstein, M., Sellner, K., & Barret, J. (1996). Habitat disturbance and marina

development: an assessment of ecological effects: changes in primary production due to

dredging and marina construction. Coastal and Estuarine Federation, 19(2), 257-271.

Jowett, J. & Richardson, J. (2008). Where do Fish Want to Live? Water & Atmosphere, 16(3), 12-13.

Jowett, I. & Richardson, J. (2010). Habitat preferences of common riverine New Zealand native

fishes and implications for flow management. New Zealand Journal of Marine and

Freshwater Research, 29(1), 13-23.

Joy, M., David, B., Lake, M. (2013). New Zealand Freshwater Fish Sampling Protocols: Wadeable

Rivers and Streams. Massey University: Palmerston North.

King Country Energy Limited. (n.d.). Kuratau Power Station [Factsheet]. Retrieved from

http://www.kce.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/Kuratau.pdf.

King Country Energy Limited. (2000). Kuratau Power Scheme: Resource Consent Applications and

Assessment of Effects on the Environment [Resource Consent Application], Volume Two

(Draft). New Zealand: Author.

King Country Energy Limited. (2013). Re: Submission on the Proposed Southern Settlement

Structure Plan [Submission on Proposed Southern Settlements Structure Plan]. Retrieved

from http://www.Taupōdc.govt.nz/our-council/policies-plans-and-bylaws/

structure-plans/southern-settlements-structure-plan/Pages/southern-settlements-

structure-plan.aspx.

Knight, R.L. (1992). Ancillary benefits and potential problems with the use of wetlands for nonpoint](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eaa0df4b-347e-43e8-b498-a43ef1dd3d8d-150710002958-lva1-app6892/85/EIA-FINAL-160-320.jpg)

![161

188.763, 2013, EIA.

source pollution control. Ecological Engineering, 1, (1-2): 97-113.

Kuratau Omori Preservation Society. (2013). Submission of the Kuratau Omori Preservation

Society Inc. [Submission on Proposed Southern Settlements Structure Plan]. Retrieved

from http://www.Taupōdc.govt.nz/our-council/policies-plans-and-bylaws/structure-

plans/southern-settlements-structure-plan/Pages/southern-settlements-structure-

plan.aspx.

La Follette, C. & Thomas, R. (2013). The Nehalem Dredging Saga (article), In Tillamook Headlight

Herald. Retrieved from http://www.tillamookheadlightherald.com/news/article_3f1c5766-

a15c-11e2-b8dc-0019bb2963f4.html on 11/04/2013.

Landcare Research (n.d). S-Maps Online. Retrieved from http://smap.landcareresearch.co.nz.

Landcare Research (2013a). S-Map Soil Report: N_250_2.1. Retrieved From http://smap.

landcareresearch.co.nz..

Landcare Research (2013b). S-Map Soil Report: Taup_27.1. Retrieved From http://smap.

landcareresearch.co.nz..

Lewis, J. & Lewis, R. (2013). Written Submission [Submission on Proposed Southern Settlements

Structure Plan]. Retrieved from http://www.Taupōdc.govt.nz/our-council/

policies-plans-and-bylaws/structure-plans/southern-settlements-structure-

plan/Pages/southern-settlements-structure-plan.aspx.

Lowrance, R., Todd, R., Fail, J., Hendrickson, O., Leonard, R. & Asmussen, L. (1984). Riparian Forests

as Nutrient Filters in Agriculture Watersheds. Bioscience. 34(6), 374-377.

Matthaei, C., Weller, F., Kelly, D., & Townsend, C. (2006). Impacts of fine sediment addition to

tussock, pasture, dairy and deer farming streams in New Zealand. Freshwater Biology,

51(11), 2154-2172.

McKinlay, B. & Smale, A. (2001). The effect of jetboat wake on braided riverbed birds on the

Dart River. Notornis, 48, 72-75.

Mighty River Power, (2013). Lake Levels- Lake Taupō. Retrieved from

www.mightyriver.co.nz/Our-Buisness/Generation/Lake-Levels.aspx last updated April 2013

Ministry for Agriculture, Forestry and Fishing (Biosecurity). (2008). National Pest Plant Accord.

Retrieved from www.biosecurity.govt.nz/mppa.

Ministry for the Environment. (2006). Identifying, Investigating, and Managing Risks Associated

with Former Sheep-dip Sites: a Guide for Local Authorities. Wellington: Author.

Moore, T., & Hunt, W. (2012). Ecosystem service provision by stormwater wetlands and ponds: a

means for evaluation? Water Research, 6811-6823.

Nassauer, J., Allan, J., Johengen, T., Kosek, S., & Infante, D. (2004). Exurban residential subdivision

development: effects on water quality and public perception. Urban Ecosystems, 7(3),

267-281.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eaa0df4b-347e-43e8-b498-a43ef1dd3d8d-150710002958-lva1-app6892/85/EIA-FINAL-161-320.jpg)

![162

188.763, 2013, EIA.

National Instituted for Water and Atmosphere. (1997). Kuratau River Instream Habitat

Requirements [Client Report]. KCE70202: Author.

Oschwald, W. (1972). Sediment-water interactions. Journal of Environmental Quality, 1(4),

360-366.

Resource Management Act, No. 69. (1991). Retrieved from http://www.legislation.govt.nz.

Resource Management Regulations: National Environmental Standards for Air Quality, No. 309.

(2004). Retrieved from http://www.legislation.govt.nz.

Resource Management Regulations: National Environmental Standards for Assessing and

Managing Contaminants in Soil to Protect Human Health, No. 361. (2011). Retrieved

from http://www.legislation.govt.nz.

Resource Management Regulations: National Environment Standards for Electricity

Transmission Activities, No. 397. (2009). Retrieved from http://www.legislation.govt.nz.

Reynoldson, T., Metcalfe-Smith, J. (1992). An overview of the assessment of aquatic ecosystem

health using benthic invertebrates. Journal of Aquatic Ecosystem Health, 1(4), 295-

308.

Richards, S. (2012). Comment [Submission on Proposed Southern Settlements Structure Plan].

Retrieved from http://www.Taupōdc.govt.nz/our-council/policies-plans-and-bylaws/

structure-plans/southern-settlements-structure-plan/Pages/southern-settlements-

structure-plan.aspx.

Statistics New Zealand. (2006). Census. Retrieved from http://www.statsnz.govt.nz.

Taranaki Regional Council. (2009). A Photographic Guide to Freshwater Invertebrates of Taranaki’s

Rivers and Streams. Taranaki: Author.

Taupō District Council. (1990). Reserves and Development Incentives. Retrieved from http://

www.Taupōdc.govt.nz/our-council/policies-plans-and-bylaws/policies/Documents/

Reserve-And-Development-Incentives-1990.pdf.

Taupō District Council. (2006). Taupō District 2050: District Growth Management Strategy.

Retrieved from http://www.Taupōdc.govt.nz/our-council/policies-plans-and-bylaws/

district-strategies/td2050-growth-management-strategy/Pages/default.aspx .

Taupō District Council. (2007). Taupō District Plan. Retrieved from http://www.Taupōdc.govt.

nz/our-council/policies-plans-and-bylaws/district-plans/current-version/Pages/

current-version.aspx.

Taupō District Council. (2009). Code of Practice for Development of Land. Retrieved from

http://www.Taupōdc.govt.nz/our-council/policies-plans-and-bylaws/policies/

Documents/Code-of-Practice-Development-of-land-2009.pdf.

Taupō District Council. (2012a). Proposed Southern Settlements Structure Plan. Retrieved

from http://www.Taupōdc.govt.nz/our-council/policies-plans-and-bylaws/structure-

plans/southern-settlements-structure-plan/Documents/Proposed-Southern-

Settlements-Structure-Plan.pdf.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eaa0df4b-347e-43e8-b498-a43ef1dd3d8d-150710002958-lva1-app6892/85/EIA-FINAL-162-320.jpg)

![163

188.763, 2013, EIA.

Taupō District Council. (2012b). Maps for Our District. Retrieved From http://apps.geocirrus.

co.nz/?Viewer=TaupōDC.

Taupō District Council. (2012c). Development Contributions Policy. Retrieved from http://www.

Taupōdc.govt.nz/our-council/policies-plans-and-bylaws/policies/Documents/

Development-Contribution-policy-2012.pdf.

Taupō District Council. (2012d). Design Guide for Rural Subdivision: Amenity and Character.

Retrieved from http://www.Taupōdc.govt.nz/our-council/policies-plans-and-bylaws/

policies/Documents/Design-Guide-for-Rural-Subdivision.pdf.

Taupō District Council (TDC), (2012e) Rubbish and Recycling Retrieved from

http://www.Taupōdc.govt.nz/our-services/rubbish-and-recycling/Pages/default.aspx

Taupō District Council (TDC), (2012f). - Wastewater Asset Management Plan: Chapter 6 Future

Demand,, July 2012. Taupō District Council.

TradeMe. (2013, April 9). Marina Berths. Retrieved April 9, 2013, from TradeMe:

http://www.trademe.co.nz/motors/boats-marine/marina-berths

Tromans, D. (1998). Temperature and pressure dependent solubility of oxygen in water: a

thermodynamic analysis. Hydrometallurgy, 48(3), 327-342.

Trustees of Pukawa. (2013). Submission on Proposed Southern Settlements Structure Plan

[Submission on Proposed Southern Settlements Structure Plan]. Retrieved from

http://www.Taupōdc.govt.nz/our-council/policies-plans-and-bylaws/structure-plans/

southern-settlements-structure-plan/Pages/southern-settlements-structure-plan.aspx.

(USEPA. (2006). Stormwater Menu of BMPs. Retrieved 04 10, 2013, from United States

Envrionmental Protection Agency:

http://cfpub.epa.gov/npdes/stormwater/menuofbmps/index.cfm?action=browse&Rbutton=

detail&bmp=39

Venture Taranaki (2007). Port Taranaki Eastern Harbour Development Costs. Accessed from

https://docs.google.com/viewer?a=v&q=cache:3nh7LJ2FS9UJ:www.taranaki.info/admin/dat

a/business/marina_development.pdf+&hl=en&gl=nz&pid=bl&srcid=ADGEEShFU93gIN_I2ZJA

jjEzjZ31N0lQWA4dFP7cKCVRwfnaZ88JQ9DasQ38Y6yujLe_JMxYjR-

YxUNZFDEdpypJGEXP3VuRo4AERvmk5oV_BUZmsO7VL1BNLIrffCp9HbPxBPNkPF6E&sig=AHIE

tbTaRLu1wg6fX8-TIflpMacawgxhzg on 11/04/2013.

Waikato Regional Council. (2012a). Land and Soil Module. Retrieved from http://www.

waikatoregion.govt.nz/PageFiles/20874/2012/Chapter_5.pdf.

Waikato Regional Council. (2012b). Water Module. Retrieved from http://www.waikatoregion.

govt.nz/PageFiles/20874/2012/Chapter_3.pdf.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eaa0df4b-347e-43e8-b498-a43ef1dd3d8d-150710002958-lva1-app6892/85/EIA-FINAL-163-320.jpg)

![164

188.763, 2013, EIA.

Waikato Regional Council. (2013a). About Resource Consents. Retrieved from http://www.

waikatoregion.govt.nz/Services/Regional-services/Consents/Resource-consents/

About-consents.

Waikato Regional Council. (2013b). Protecting Lake Taupō: A Long Term Strategic Partnership.

Retrieved from http://www.waikatoregion.govt.nz/PageFiles/7058/strategy.pdf.

Waikato Regional Council. (2013c). Comments to Taupō District Council: Proposed Southern

Settlements Structure Plan [Submission on Proposed Southern Settlements Structure

Plan]. Retrieved from http://www.Taupōdc.govt.nz/our-council/policies-plans-and-

bylaws/structure-plans/southern-settlements-structure-plan/Pages/southern-

settlements-structure-plan.aspx.

Waitomo caves. (n.d.). All about: Bats. Retrieved from

www.waitomocaves.com/downloads/bats.pdf.

Wardle, P. (1985). Environmental nfluences on the Vegetation of New Zealand. New Zealand Journal

of Botnay. 23(4), 773-788.

Welch, E., Quinn, J., & Hickey, C. (1992). Periphyton biomass related to point-source nutrient

enrichment in seven New Zealand streams. Water Research, 26(5), 669-675.

Wong, T.H.F. & Somes, N.L.G. (1995) A Stochastic Approach to Designing Wetlands for Stormwater

Pollution Control. Water Science and Technology, 32 (1):- 145-151.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eaa0df4b-347e-43e8-b498-a43ef1dd3d8d-150710002958-lva1-app6892/85/EIA-FINAL-164-320.jpg)

![172

188.763, 2013, EIA.

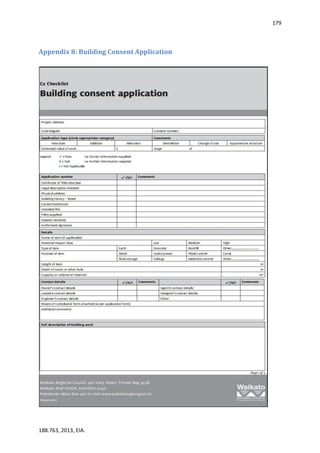

Appendix 5: Application Form for a Notice to Environment Court of appeal

or inquiry on decision or recommendation on application concerning

restricted coastal activity, resource consent, water permit, certificate of

compliance, or esplanade strip

Sections 118(6), 121, 127(3), 132(2), 136(4)(b), 139(6), and 234(4), Resource

Management Act 1991

To the Registrar

Environment Court

Auckland, Wellington, and Christchurch

I, [full name], appeal a decision (or part of a decision) (or seek an inquiry of a recommendation or

part of a recommendation) on the following matter:

[briefly describe the application or the review of consent conditions to which the appealed decision or

recommendation relates in enough detail to identify the relevant matter].

I am the applicant (or I am the consent holder or I made a submission on that application or review

of consent conditions).

I received notice of the decision (or recommendation) on [date].

The decision (or recommendation) was made by [name of authority, Minister, or committee].

The decision (or recommendation or part of the decision or recommendation) I am appealing (or

seeking an inquiry of) is:

[state a summary of the decision or recommendation or part of the decision or recommendation].

The land (or resource) affected is:

[give description].

The reasons for the appeal (or inquiry) are as follows:

[set out why you are appealing or seeking an inquiry and give reasons for your views].

I seek the following relief:

[give precise details].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eaa0df4b-347e-43e8-b498-a43ef1dd3d8d-150710002958-lva1-app6892/85/EIA-FINAL-172-320.jpg)

![173

188.763, 2013, EIA.

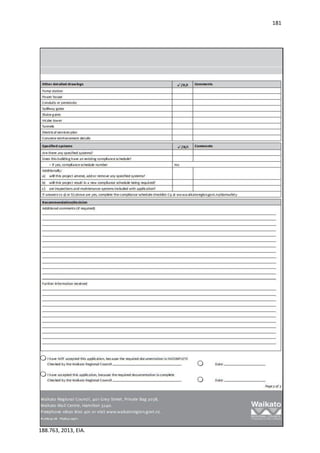

I attach the following documents* to this notice:

(a) a copy of my application (or submission or further submission (with a copy of the submission

opposed or supported by my further submission)):

(b) a copy of the relevant decision (or recommendation or part of the decision or

recommendation):

(c) any other documents necessary for an adequate understanding of the appeal or inquiry:

(d) a list of names and addresses of persons to be served with a copy of this notice.

* These documents must be attached and lodged with the notice in the Environment Court. The appellant does not need

to attach a copy of a regional or district plan or policy statement. In addition, the appellant does not need to attach

copies of the submission and decision or recommendation to the copies of this notice served on other persons if the

copy served lists these documents and state that copies may be obtained, on request, from the appellant.

......................................................................

Signature of appellant

(or person seeking inquiry

or person authorised to sign

on behalf of appellant or person

seeking inquiry)

......................................................................

Date

Address for service of appellant

(or person seeking inquiry):

Telephone:

Fax/email:

Contact person: [name and

designation, if applicable]

Note to appellant or person seeking inquiry

You may use this form to lodge an appeal and to request an inquiry.

You must lodge the original and 1 copy of this notice with the Environment Court within 15 working

days of receiving notice of the decision. The notice must be signed by you or on your behalf. You](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/eaa0df4b-347e-43e8-b498-a43ef1dd3d8d-150710002958-lva1-app6892/85/EIA-FINAL-173-320.jpg)