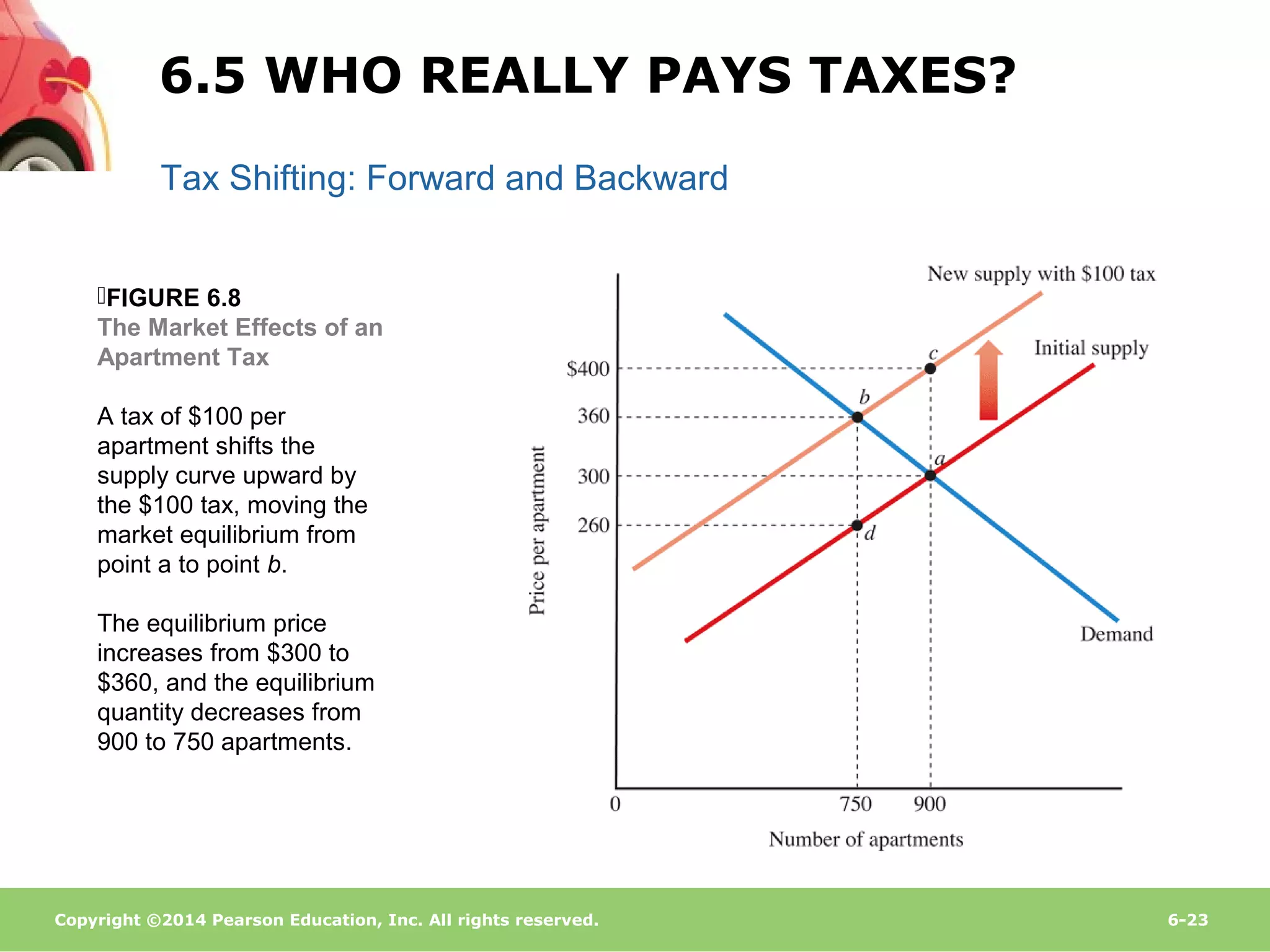

The housing market in New York City is highly regulated, issuing a small number of permits for new condominium buildings. This has resulted in rapidly rising condominium prices as demand has grown. The chapter discusses market efficiency and government intervention. It explains how the market equilibrium maximizes total surplus when there are no externalities, perfect information, and perfect competition. Government policies like price controls and import restrictions can decrease total surplus and cause inefficiency in the market.