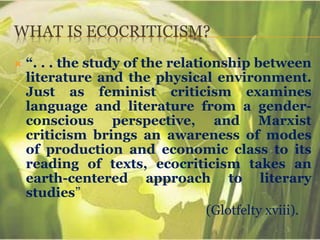

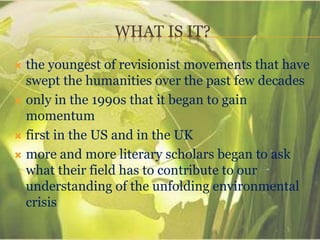

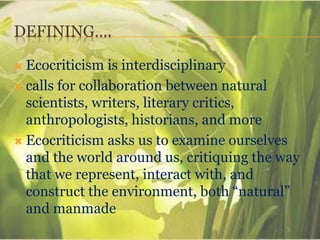

Ecocriticism examines the relationship between literature and the physical environment, advocating an earth-centered approach akin to feminist and Marxist criticisms. Emerging in the 1990s, it incorporates interdisciplinary perspectives, assessing how cultures construct and are shaped by their interactions with the non-human world, while considering the implications of nature representations in literature. Key influences include Rachel Carson's work and American transcendentalists, with contemporary discussions evolving around topics like ecofeminism and the societal constructs of wilderness.

![DEFINING

At the heart of ecocriticism is “a commitment

to environmentality from whatever critical

vantage point” (Buell)

The “challenge” for ecocritics is “keep[ing]

one eye on the ways in which ‘nature’ is

always […] culturally constructed, and the

other on the fact that nature really exists”

(Gerrard).](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ecocriticismintroduction-240706132936-1a2883e8/85/Ecocriticism-in-literature-Introduction-11-320.jpg)

![BRANCHES…

Greg Gerrard identifies three branches of the

pastoral:

Classic Pastoral, “characterized by nostalgia” and

an appreciation of nature as a place for human

relaxation and reflection

Romantic Pastoral, a period after the Industrial

Revolution that saw “rural independence” as

desirable against the expansion of the urban

American Pastoralism, which “emphasize[d]

agrarianism” and represents land as a resource to be

cultivated, with farmland often creating a boundary

between the urban and the wilderness](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ecocriticismintroduction-240706132936-1a2883e8/85/Ecocriticism-in-literature-Introduction-19-320.jpg)