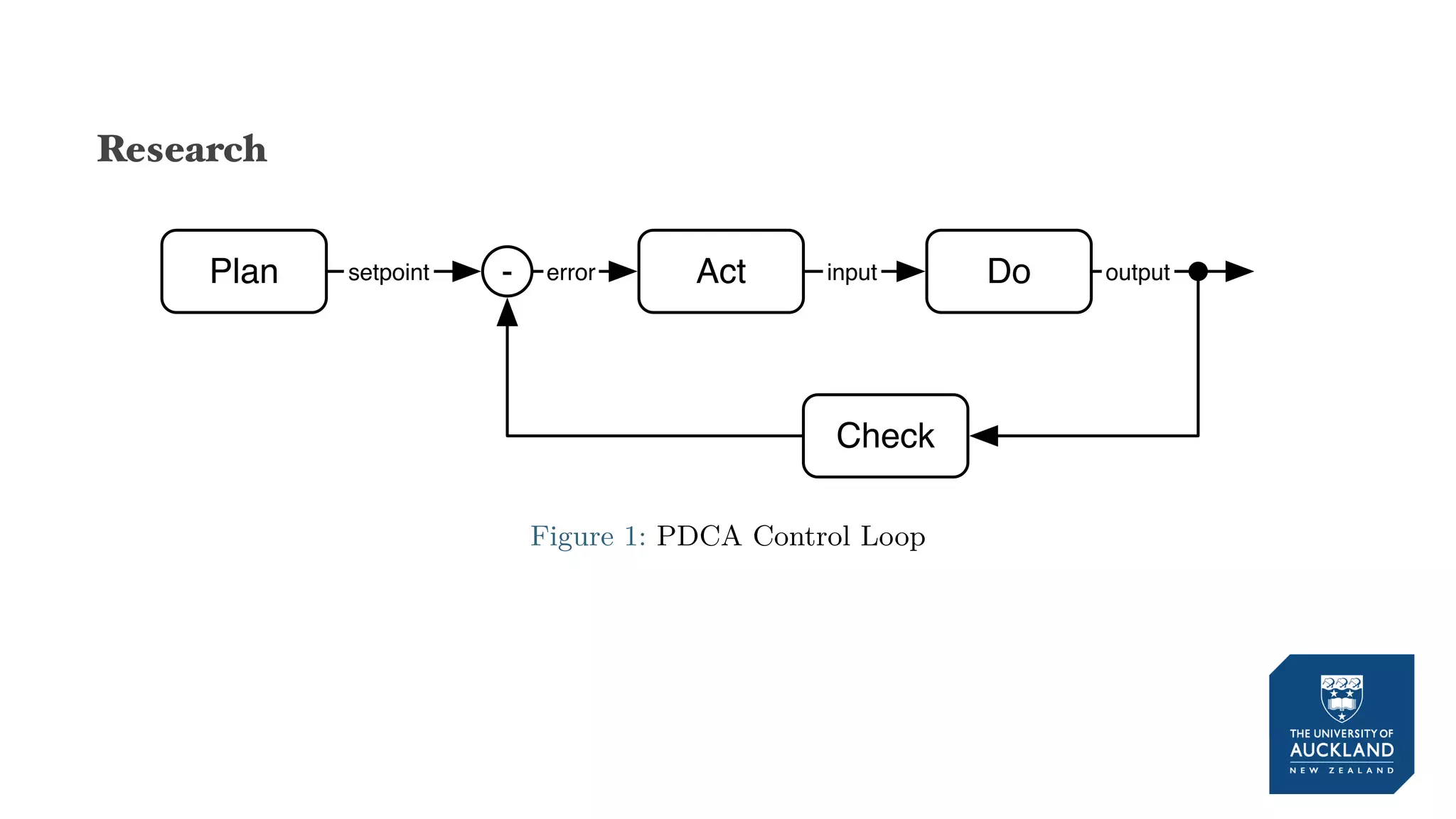

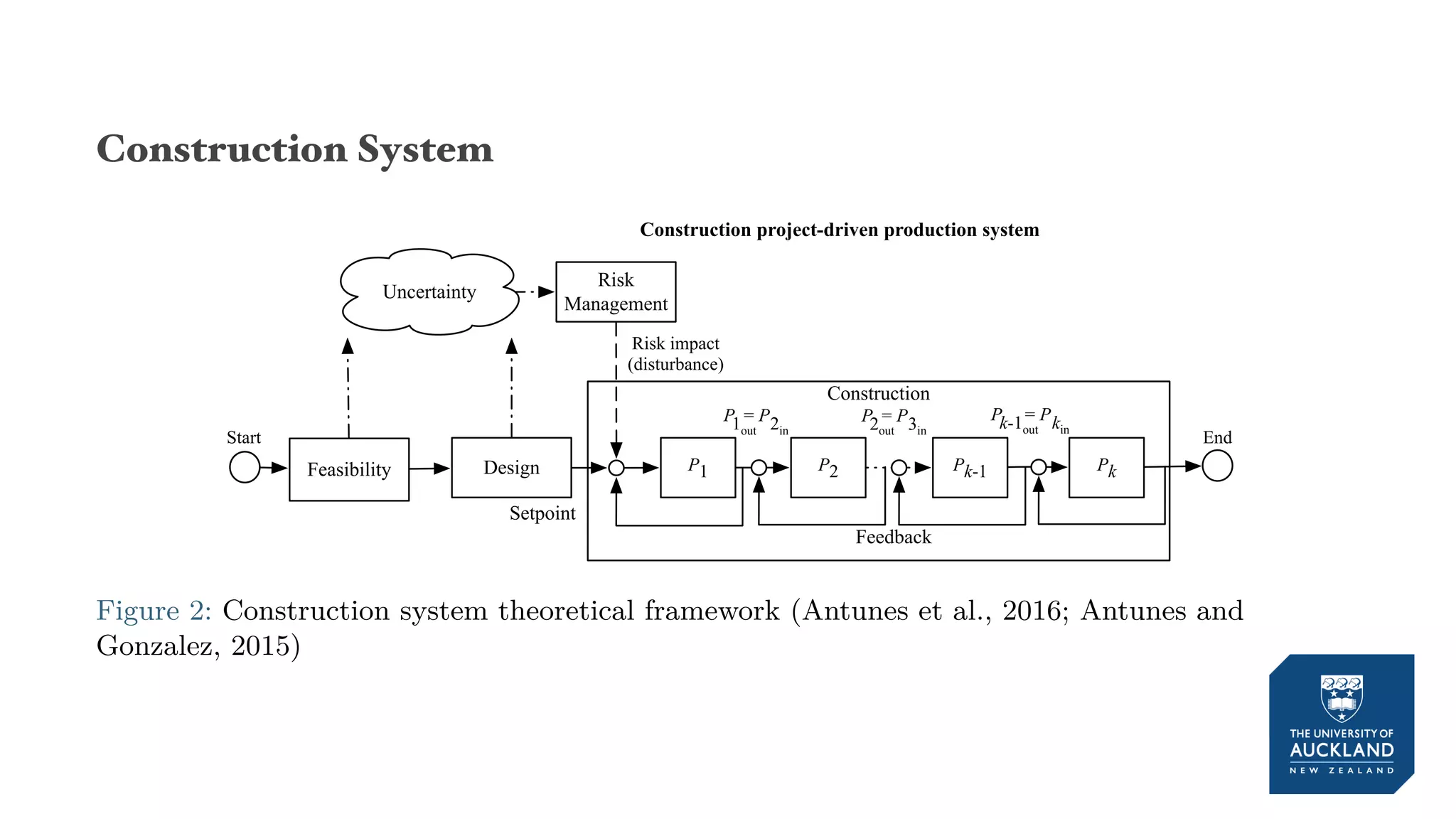

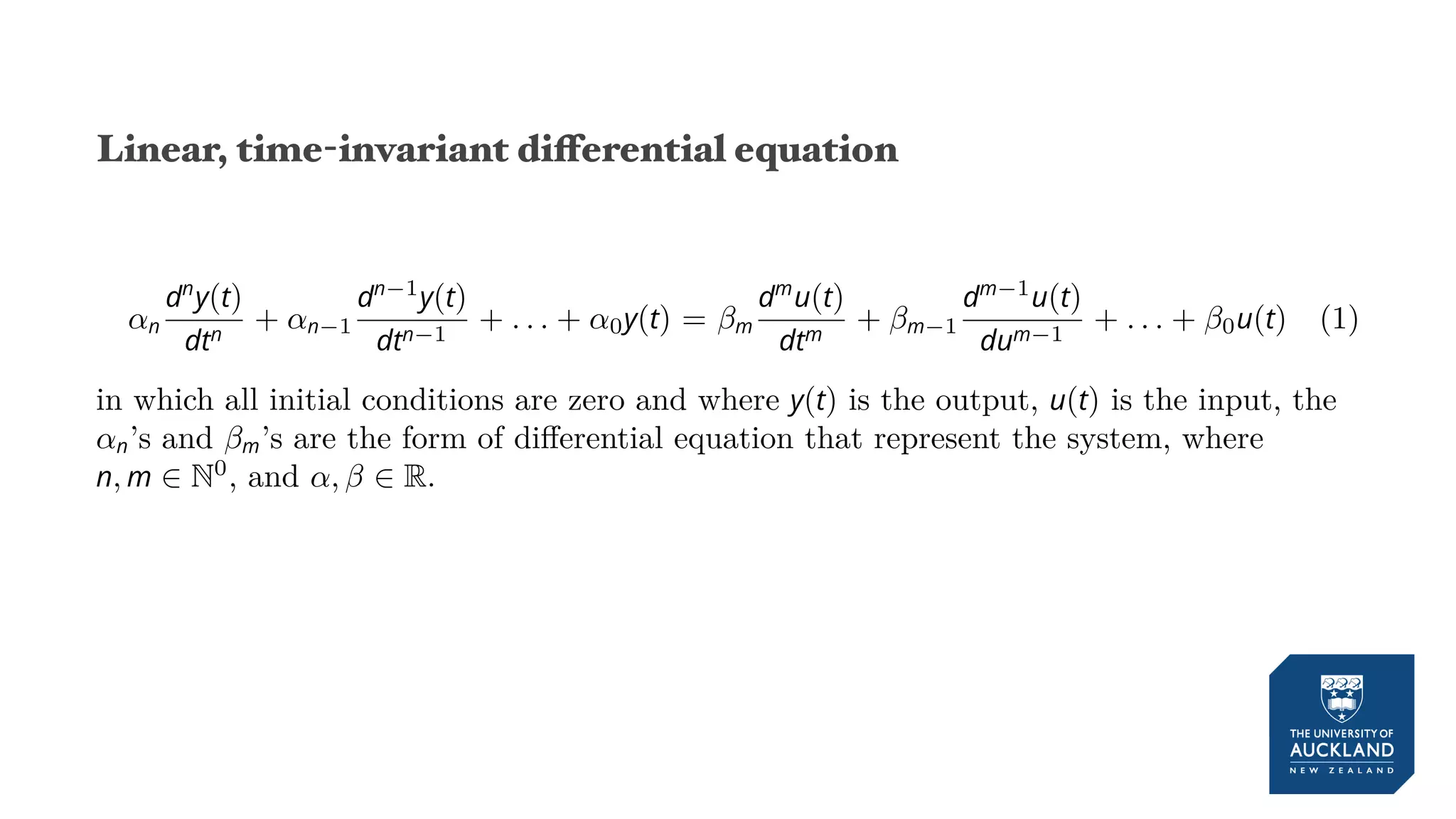

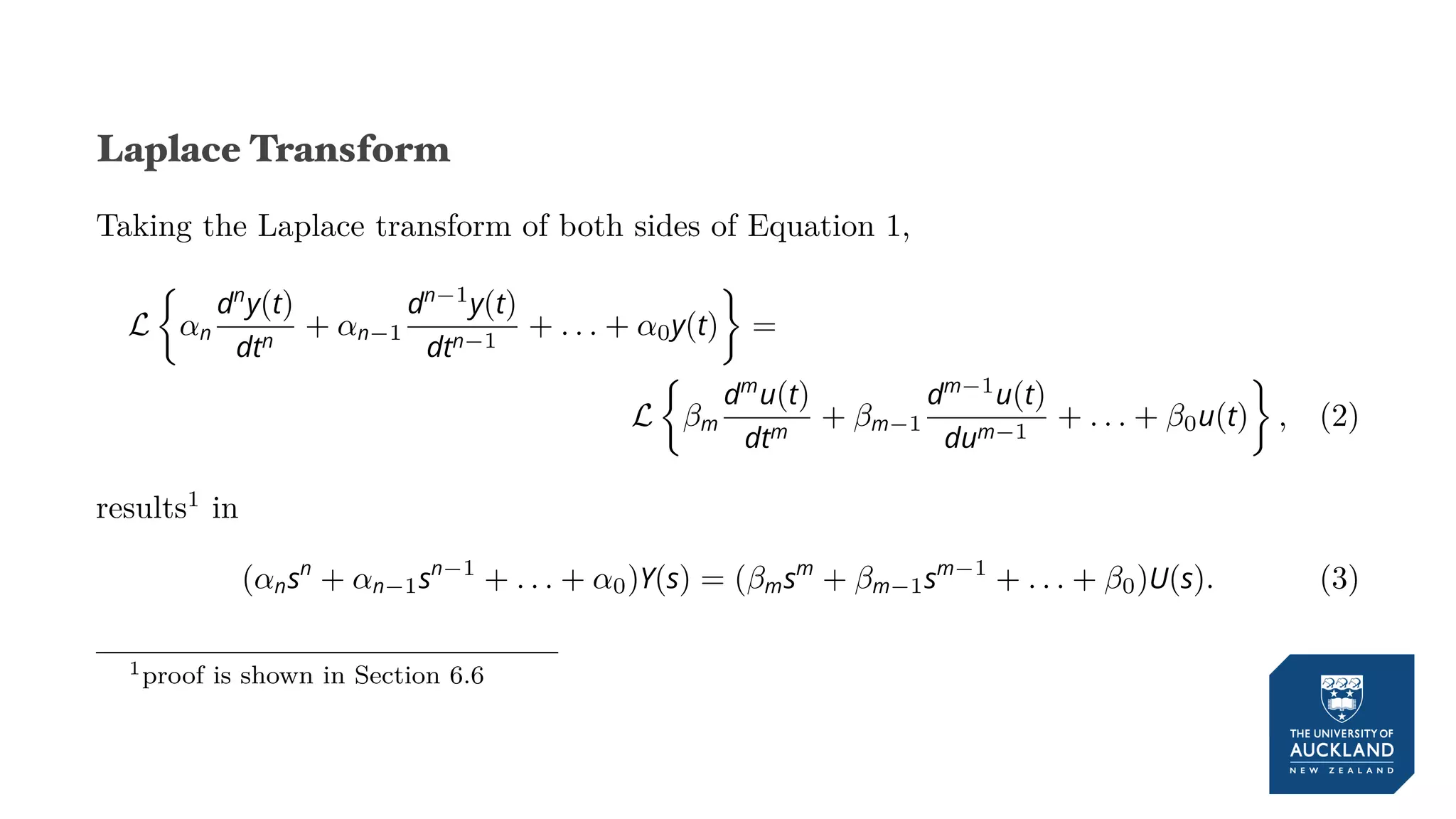

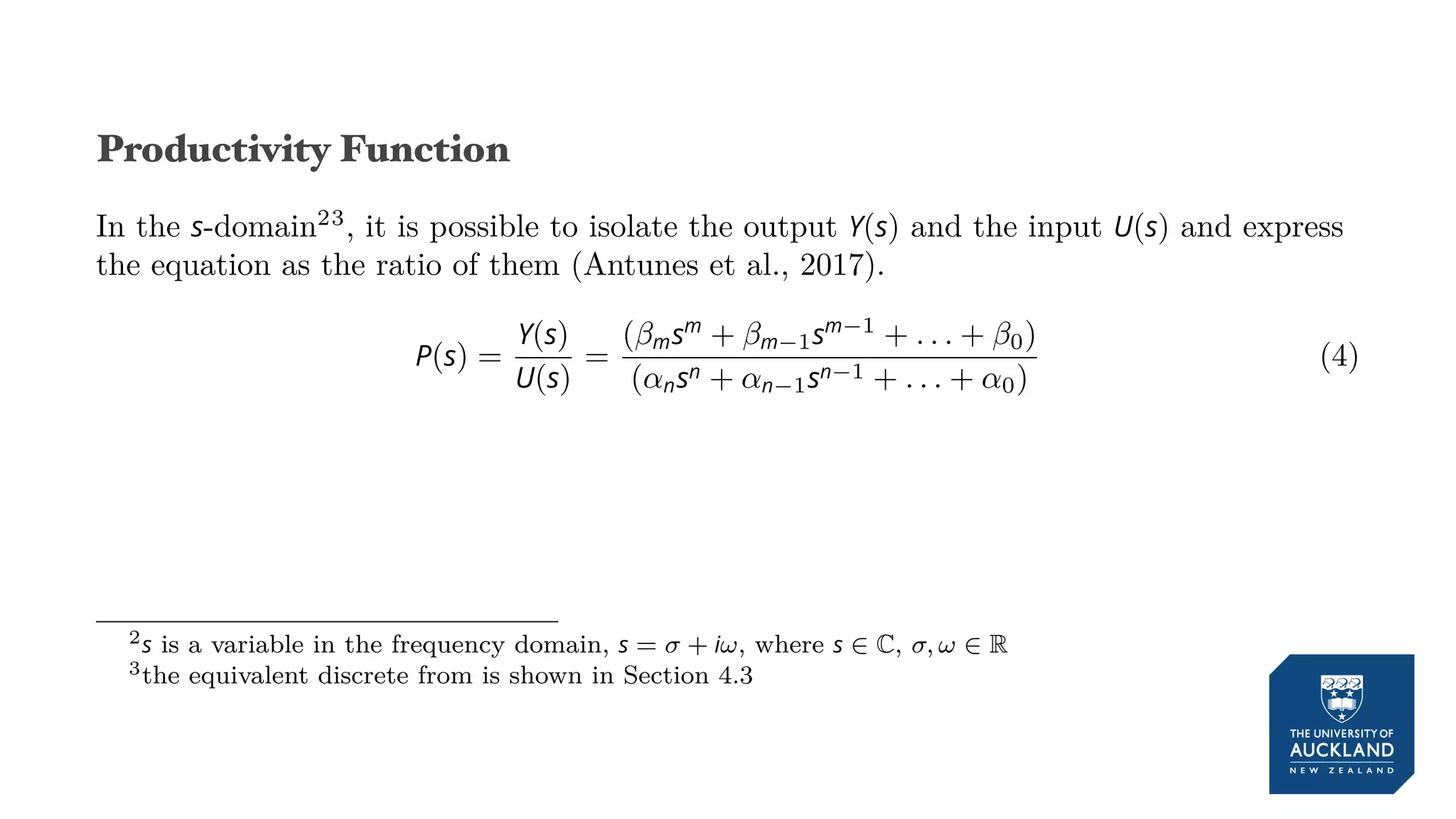

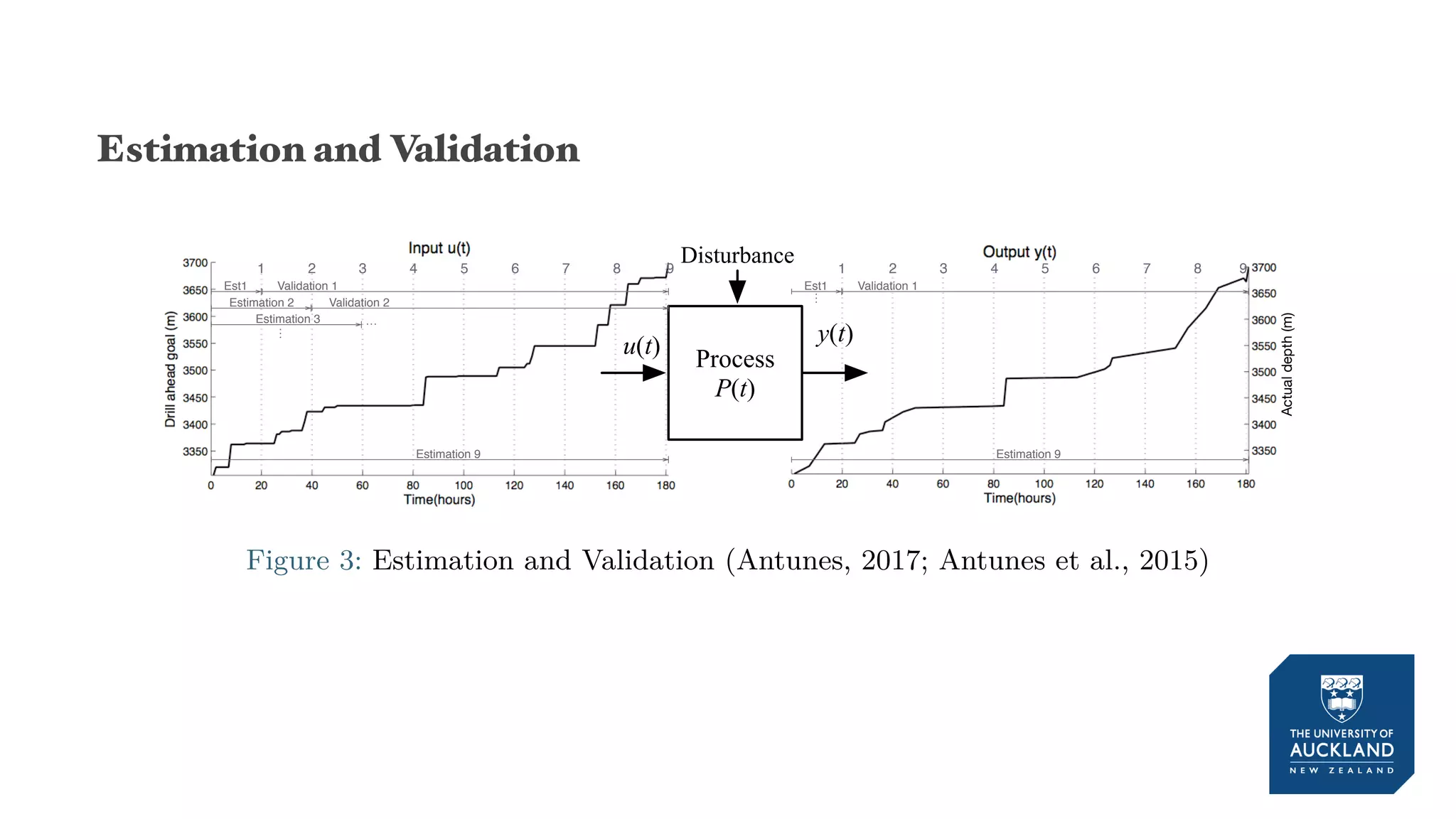

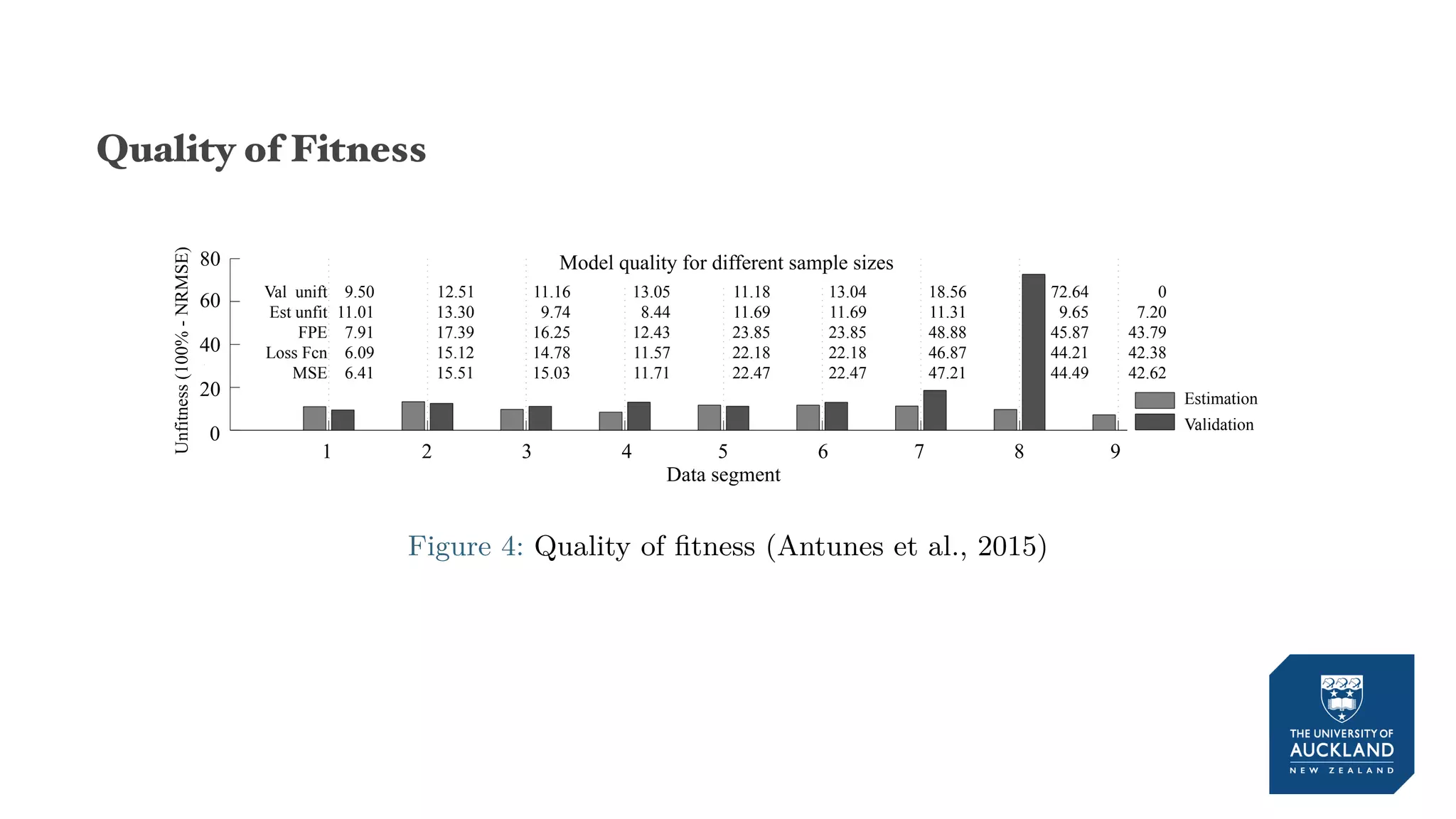

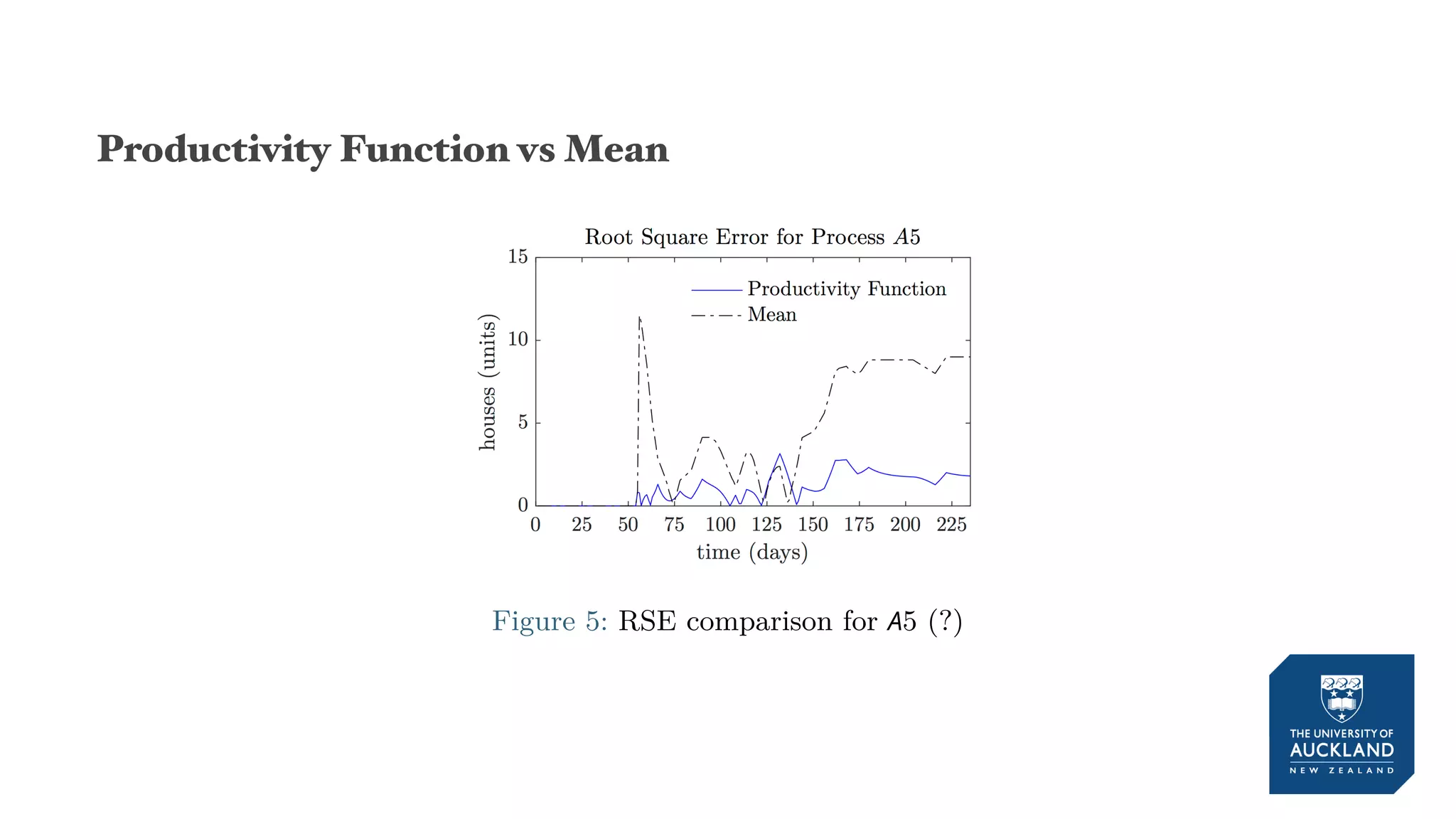

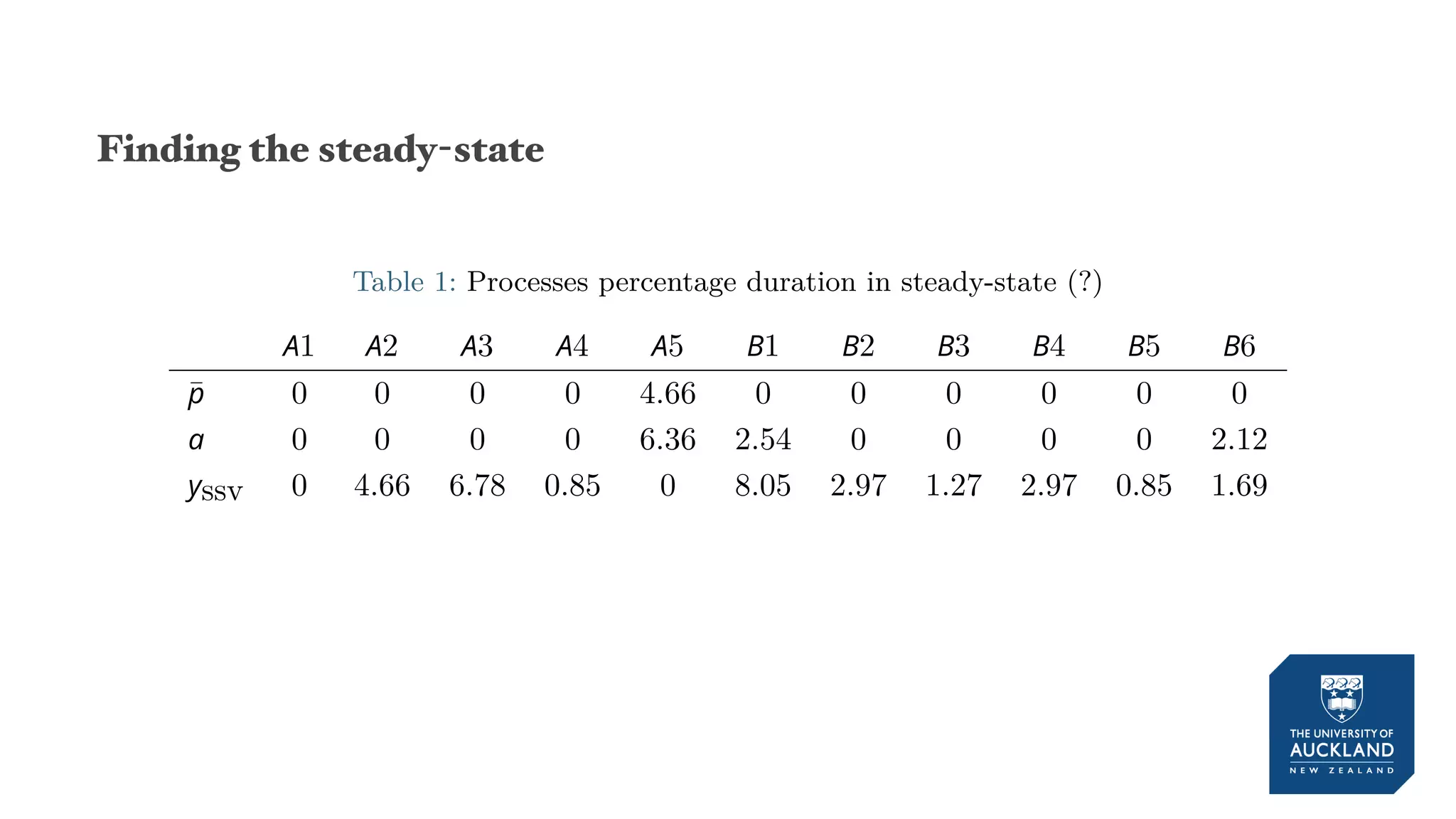

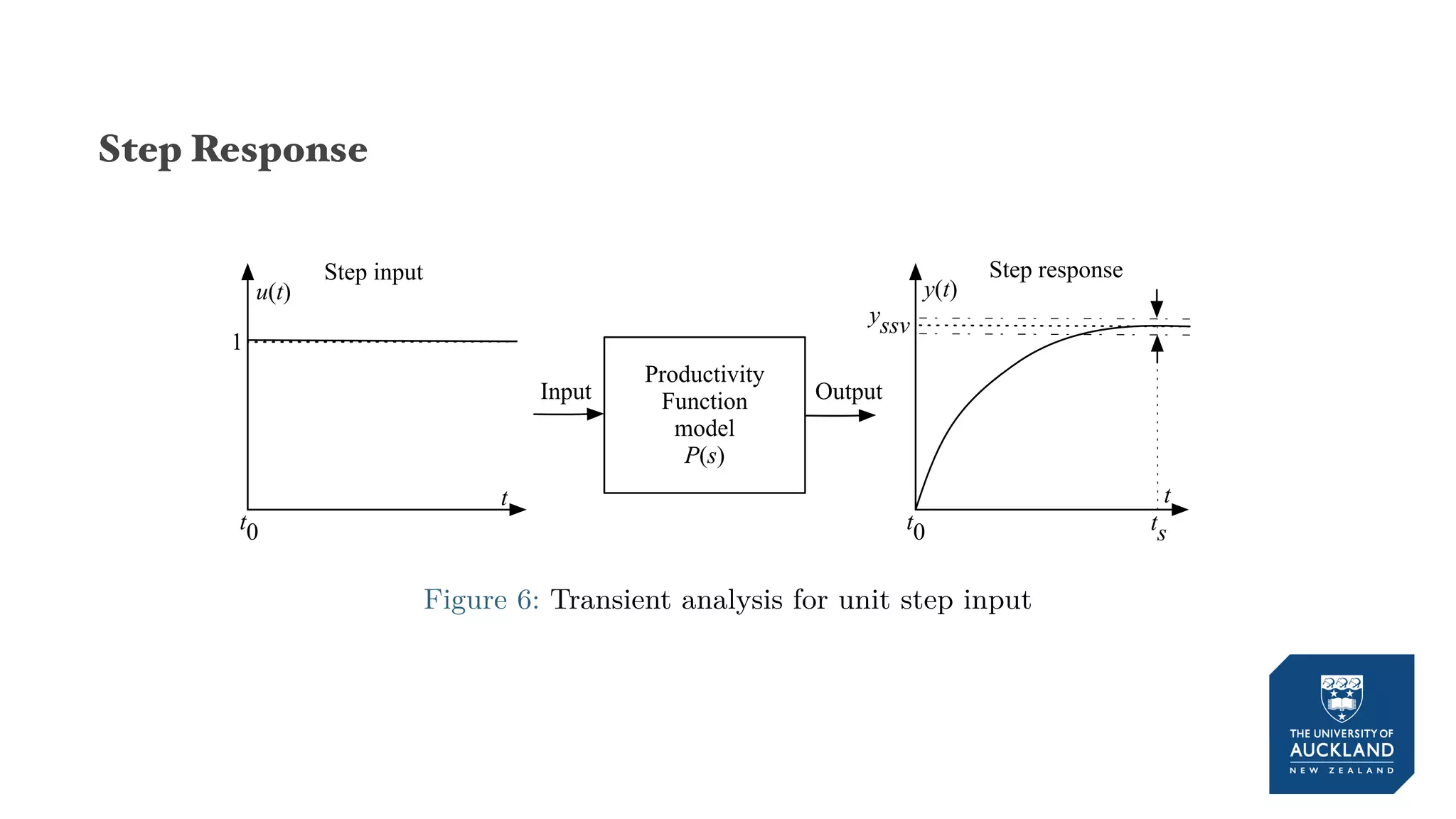

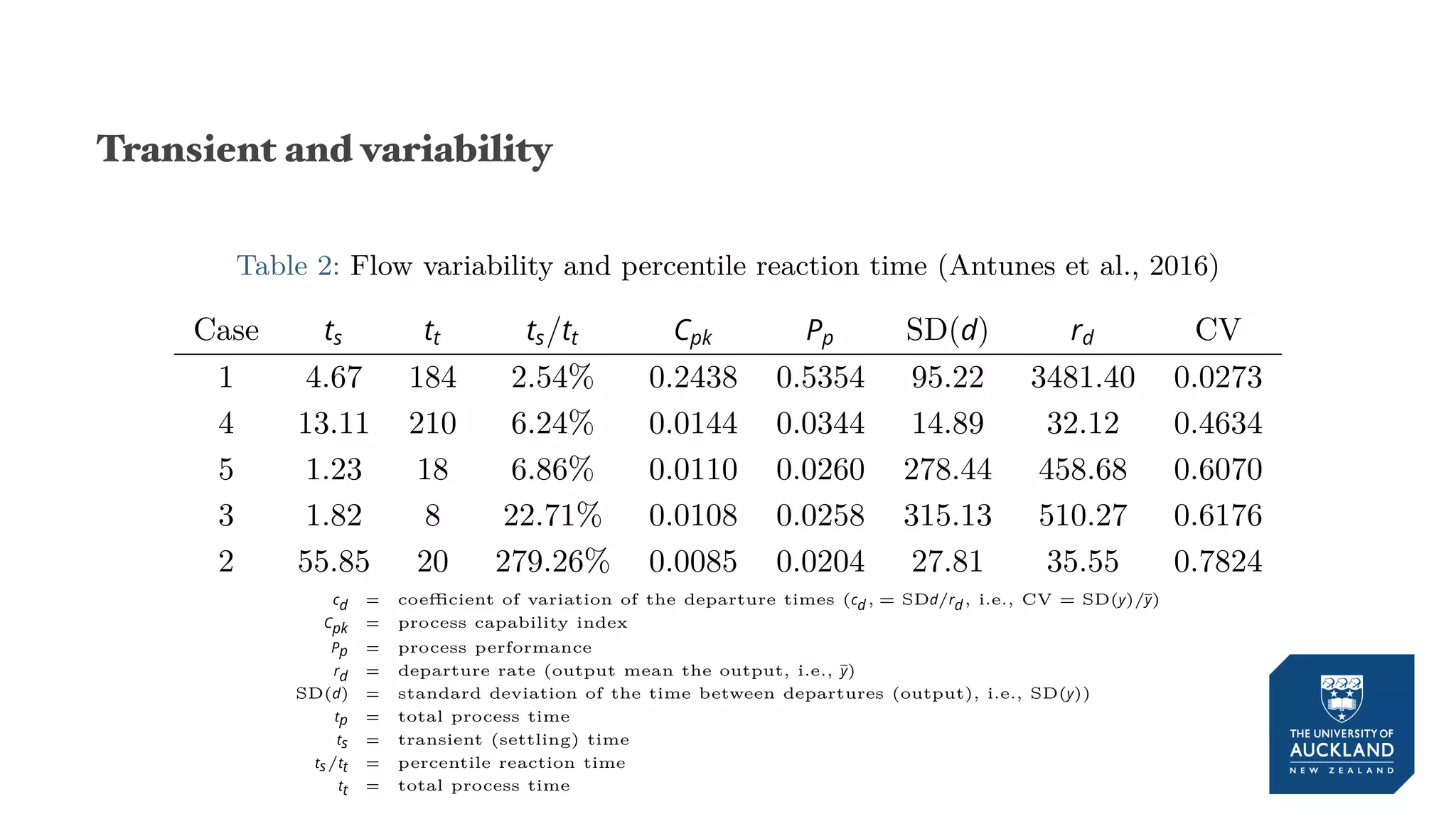

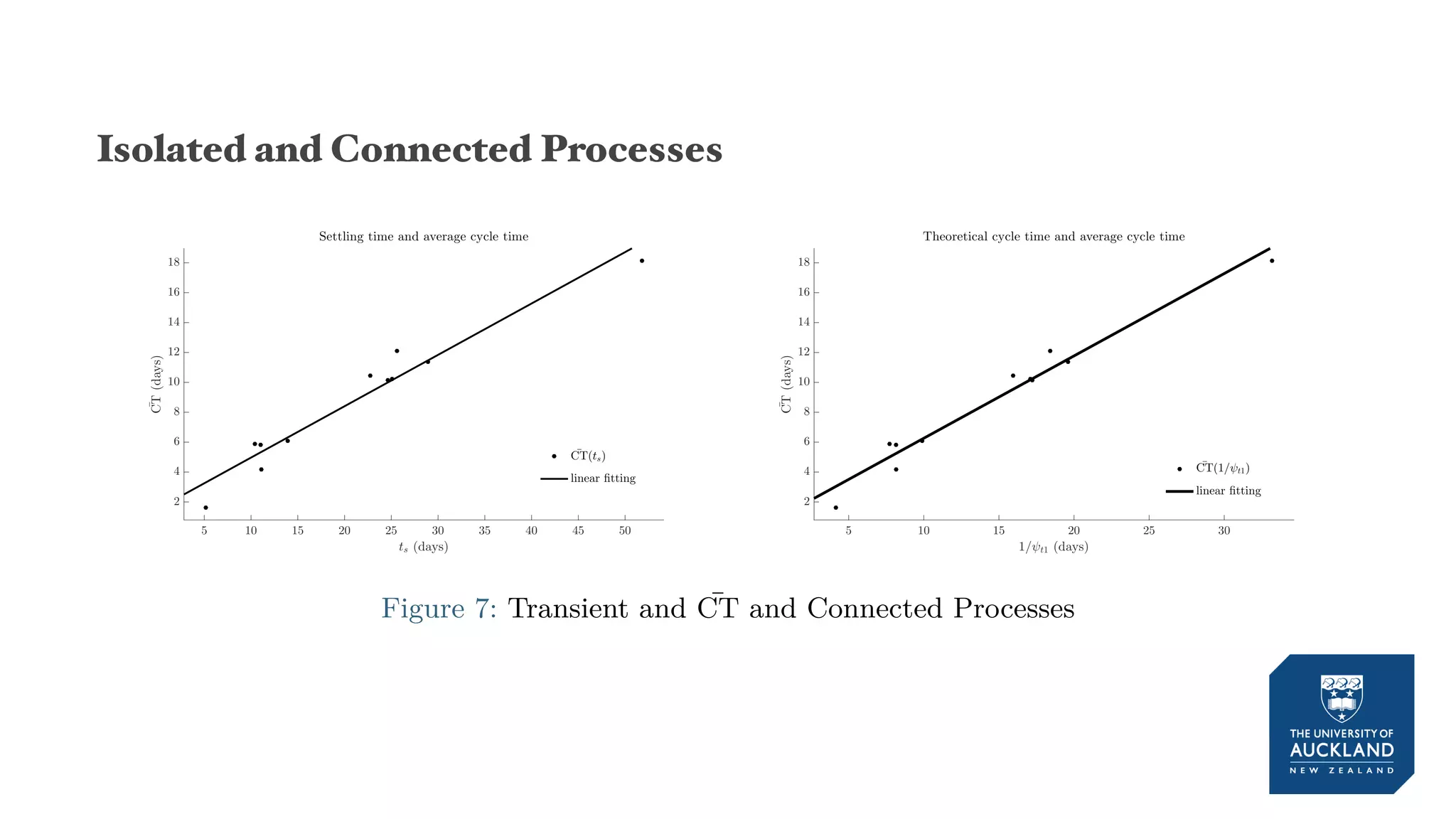

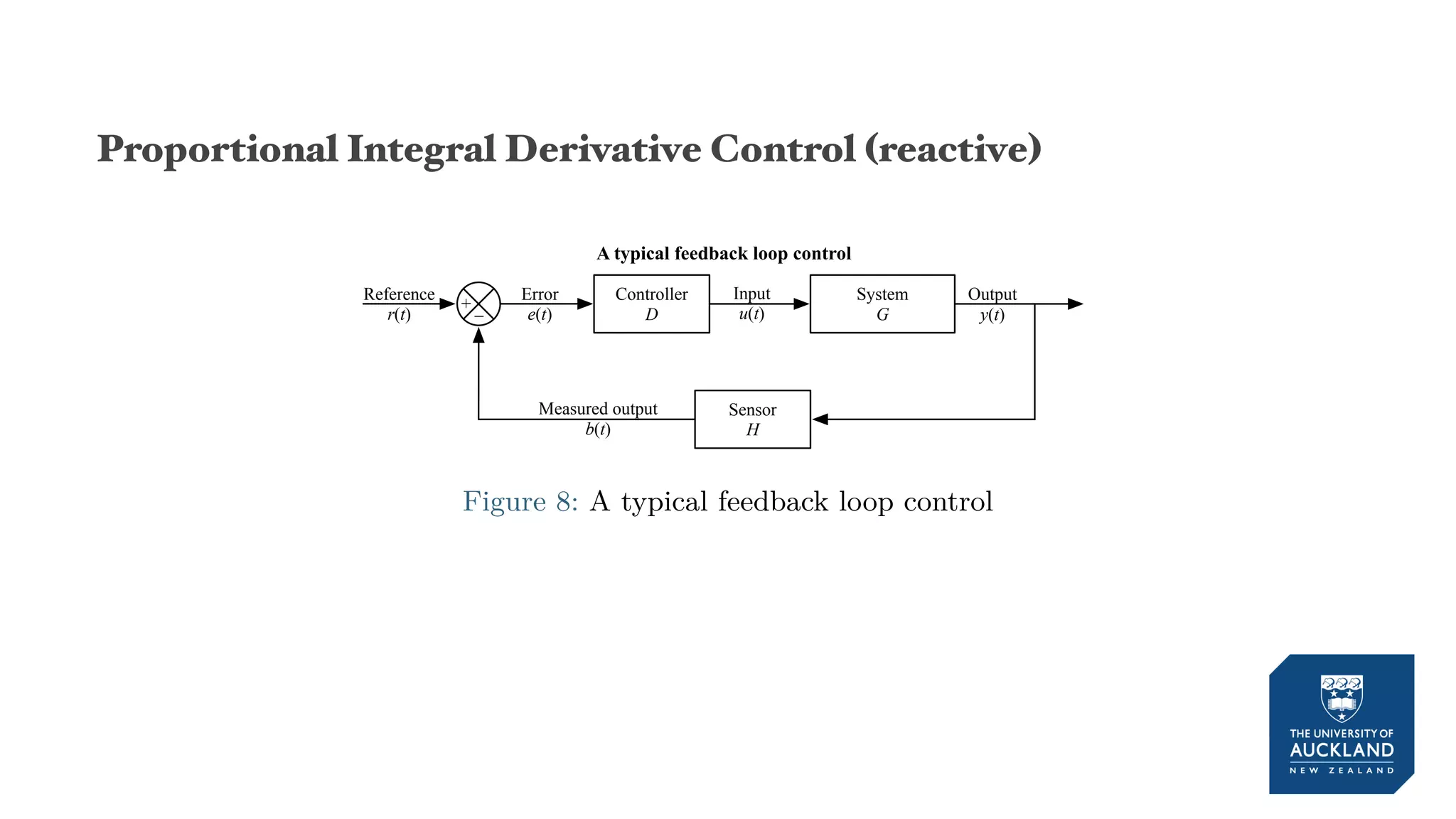

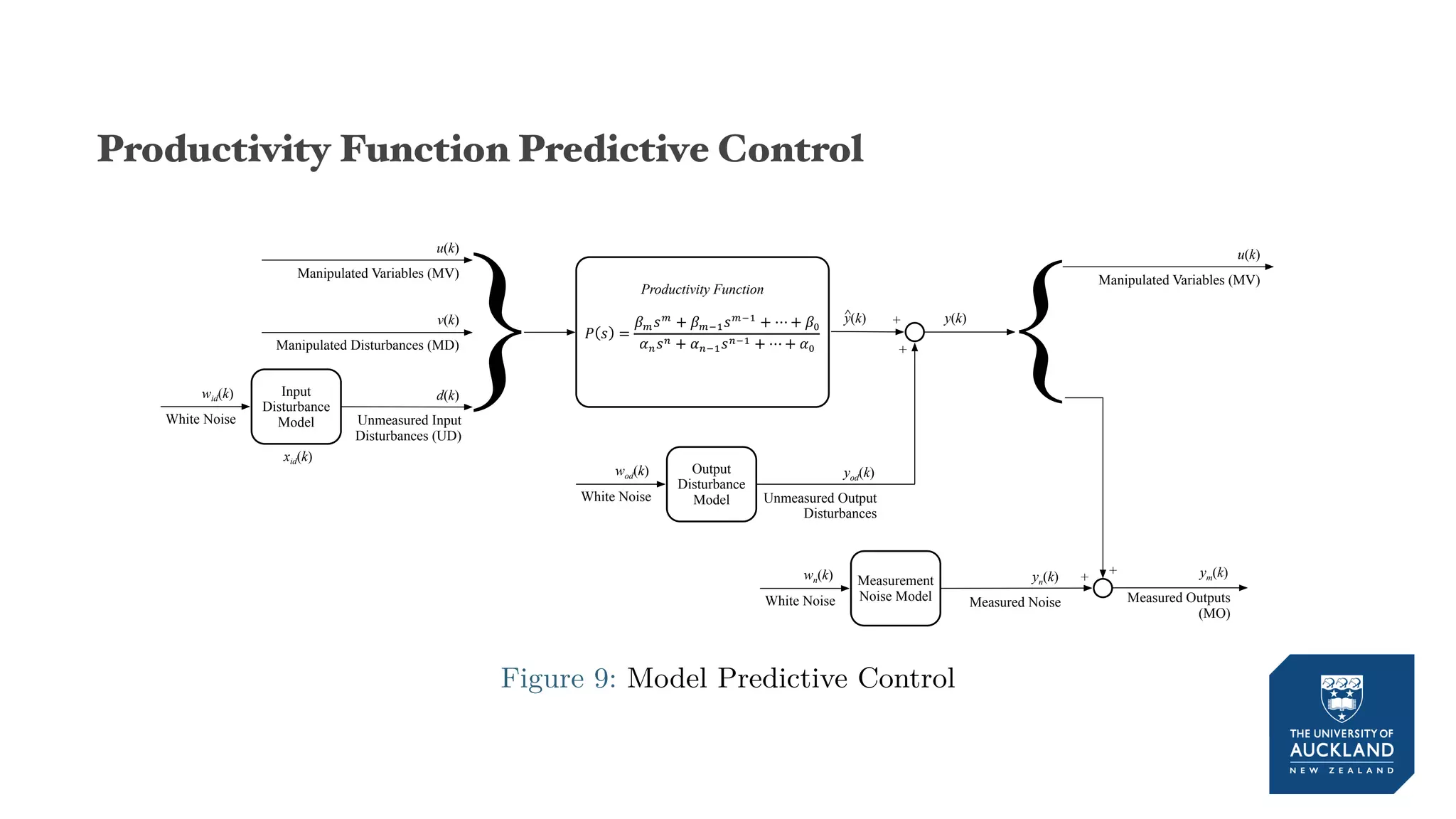

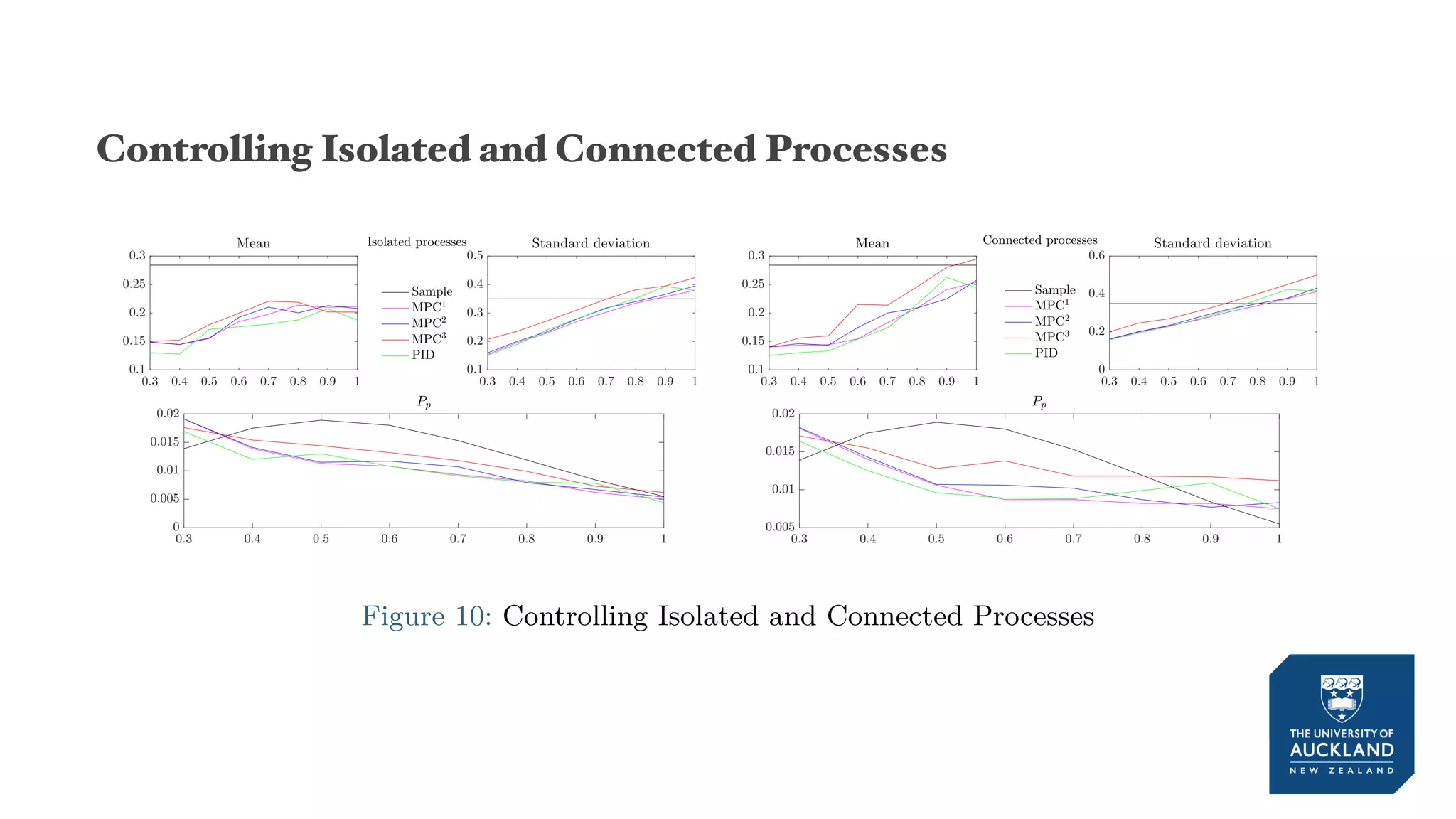

The document discusses a production model for repetitive processes in construction, focusing on the dynamics of project-driven systems. It emphasizes the importance of including transient states in modeling to enhance accuracy and provides methods for estimating productivity functions. Additionally, it highlights findings related to process variability and control methodologies while addressing limitations and future research directions.