This document summarizes the discovery of a stellar tidal stream around the nearby dwarf galaxy NGC 4449 using deep imaging. The stream implies a massive dwarf spheroidal progenitor that is disrupting and depositing stars into NGC 4449's halo. The luminosity ratio between the two galaxies is around 1:50, but their dynamical mass ratio including dark matter may be 1:10-1:5. This "stealth merger" suggests that satellite accretion can significantly build up stellar halos of low-mass galaxies and possibly trigger their starbursts.

![Draft version December 12, 2011

Preprint typeset using L TEX style emulateapj v. 5/2/11

A

DWARFS GOBBLING DWARFS: A STELLAR TIDAL STREAM AROUND NGC 4449

AND HIERARCHICAL GALAXY FORMATION ON SMALL SCALES

David Mart´ ınez-Delgado1,13 , Aaron J. Romanowsky2 , R. Jay Gabany3 , Francesca Annibali4 , Jacob A. Arnold2 ,

¨ rgen Fliri5,6 , Stefano Zibetti7 , Roeland P. van der Marel8 , Hans-Walter Rix1 , Taylor S. Chonis9 , Julio A.

Ju

Carballo-Bello10 , Alessandra Aloisi8 , Andrea V. Maccio1 , J. Gallego-Laborda11 , Jean P. Brodie2 , Michael R.

`

Merrifield12

(Received; Accepted)

Draft version December 12, 2011

arXiv:1112.2154v1 [astro-ph.CO] 9 Dec 2011

ABSTRACT

We map and analyze a stellar stream in the halo of the nearby dwarf starburst galaxy NGC 4449,

detecting it in deep integrated-light images using the Black Bird Observatory 0.5-meter telescope,

and resolving it into red giant branch stars using Subaru/Suprime-Cam. The properties of the stream

imply a massive dwarf spheroidal progenitor, which will continue to disrupt and deposit an amount

of stellar mass that is comparable to the existing stellar halo of the main galaxy. The ratio between

luminosity or stellar-mass between the two galaxies is ∼ 1:50, while the dynamical mass-ratio when

including dark matter may be ∼ 1:10–1:5. This system may thus represent a “stealth” merger,

where an infalling satellite galaxy is nearly undetectable by conventional means, yet has a substantial

dynamical influence on its host galaxy. This singular discovery also suggests that satellite accretion can

play a significant role in building up the stellar halos of low-mass galaxies, and possibly in triggering

their starbursts.

1. INTRODUCTION Boylan-Kolchin et al. 2011; Ferrero et al. 2011).

A fundamental characteristic of the modern cold dark To date there has been relatively little work on sub-

matter (ΛCDM) cosmological paradigm (Mo et al. 2010) structure and merging in the halos around low-mass,

is that galaxies undergo hierarchical assembly under “dwarf” galaxies. Many cases of extended stellar halos

the influence of gravity, continually accreting smaller around dwarfs have been identified observationally (see

DM halos up until the present day. If those ha- review in Stinson et al. 2009), but it is not clear if these

los contain stars, then they will be visible as satel- stars were accreted, or formed in situ. Star formation in

lites around their host galaxies, eventually disrupting dwarf galaxies is thought to occur in stochastic episodes

through tidal forces into distinct streams and shells be- (Tolstoy et al. 2009; Weisz et al. 2011), which could in

fore phase-mixing into obscurity (Cooper et al. 2010). principle be triggered by accretion events.

This picture seems to explain the existence of satel- An iconic galaxy in this context is NGC 4449, a dwarf

lites and substructures around massive galaxies in the irregular in the field that has been studied intensively as

nearby Universe (Arp 1966; Schweizer & Seitzer 1988; one of the strongest galaxy-wide starbursts in the nearby

McConnachie et al. 2009; Mart´ ınez-Delgado et al. 2010). Universe. Its absolute magnitude of MV = −18.6 makes

However, a quantitative confirmation of this aspect of it an LMC-analogue (and not formally a dwarf by some

ΛCDM has been more elusive, while there are some definitions), except that its star formation rate is ∼ 10

lingering doubts about the consonance with ΛCDM of times higher. It is strongly suspected to have recently

small-scale substructure observations (Lovell et al. 2011; interacted with another galaxy based on various signa-

tures including peculiar kinematics in its cold gas and

1 Max-Planck-Institut fur Astronomy, Heidelberg, Germany HII regions (Hartmann et al. 1986; Hunter et al. 1998),

2 University of California Observatories, Santa Cruz, CA but the nature of this interaction is unknown.

95064, USA An elongated dwarf galaxy or stream candidate near

3 Black Bird Observatory, Mayhill, New Mexico, USA

4 Osservatorio Astronomico di Bologna, INAF, Via Ranzani 1, NGC 4449 was first noticed by Karachentsev et al.

I-40127 Bologna, Italy (2007) based on Digitized Sky Survey (POSS-II) plates

5 LERMA, CNRS UMR 8112, Observatoire de Paris, 61 Av-

(object d1228+4358), which is also visible in archival

enue de l’Observatoire, 75014 Paris, France images from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS;

6 GEPI, CNRS UMR 8111, Observatoire de Paris, 5 Place

Jules Janssen, 92195 Meudon, France Abazajian et al. 2009). Here we present deep, wide-field

7 Dark Cosmology Centre, Niels Bohr Institute - University optical imaging that supplies the definitive detection of

of Copenhagen, Juliane Maries Vej 30, DK-2100 Copenhagen, this ongoing accretion event involving a smaller galaxy,

Denmark leading to interesting implications about the evolution of

8 Space Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive,

Baltimore, MD 21218 this system and of dwarf galaxies in general.

9 Department of Astronomy, University of Texas at Austin,

Texas, USA

2. OBSERVATIONS AND DATA REDUCTION

10 Instituto de Astrofisica de Canarias, Tenerife, Spain

11 Fosca Nit Observatory, Montsec Astronomical Park, Ager,

Our observations of NGC 4449 and its surroundings

Spain

consist of two main components. The first is imaging

12 School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Notting- from a small robotic telescope to confirm the presence

ham, University Park, Nottingham NG7 2RD, England of a low-surface-brightness substructure in the halo of

13 Alexander von Humboldt Fellow for Advanced Research

NGC 4449 and to provide its basic characteristics (sim-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dwarfsgobblingdwarfs-120126010833-phpapp01/75/Dwarfs-gobbling-dwarfs-1-2048.jpg)

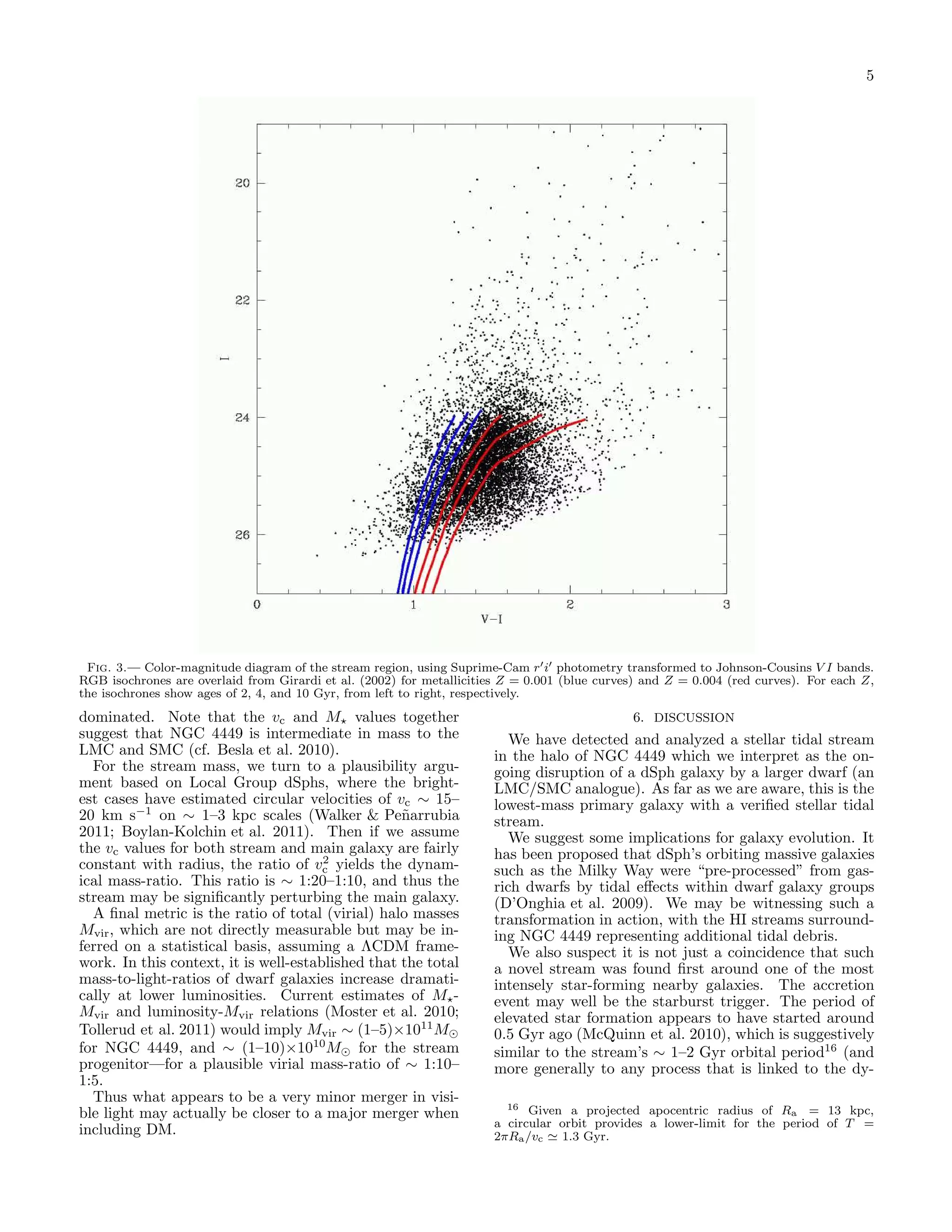

![3

Fig. 1.— NGC 4449 and its halo stream. Left: image from the BBRO 0.5-m telescope, showing a 21 × 27 kpc field. Right: 6 × 9.5 kpc

subsection of the Subaru/Suprime-Cam data, showing the stream resolved into stars. In both panels, shallower BBRO exposures in

red/green/blue filters are used to provide indicative colors.

(Mart´

ınez-Delgado et al. 2001). both Z = 0.004 and Z = 0.001. For Z = 0.004 the 2–4

Gyr isochrones trace the data reasonably well, while all

4. STELLAR POPULATIONS

Z = 0.001 models are too blue (by 0.13 mag: our sys-

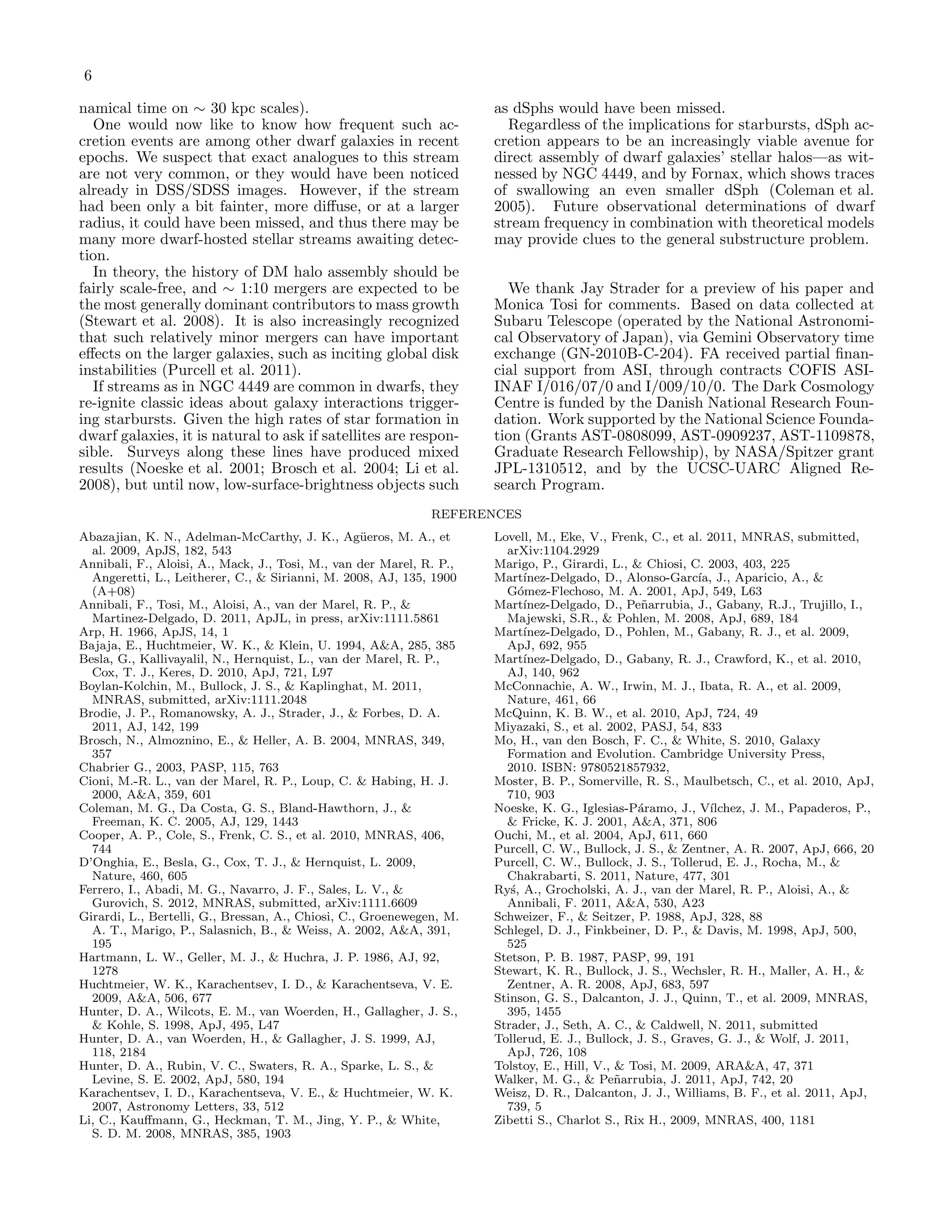

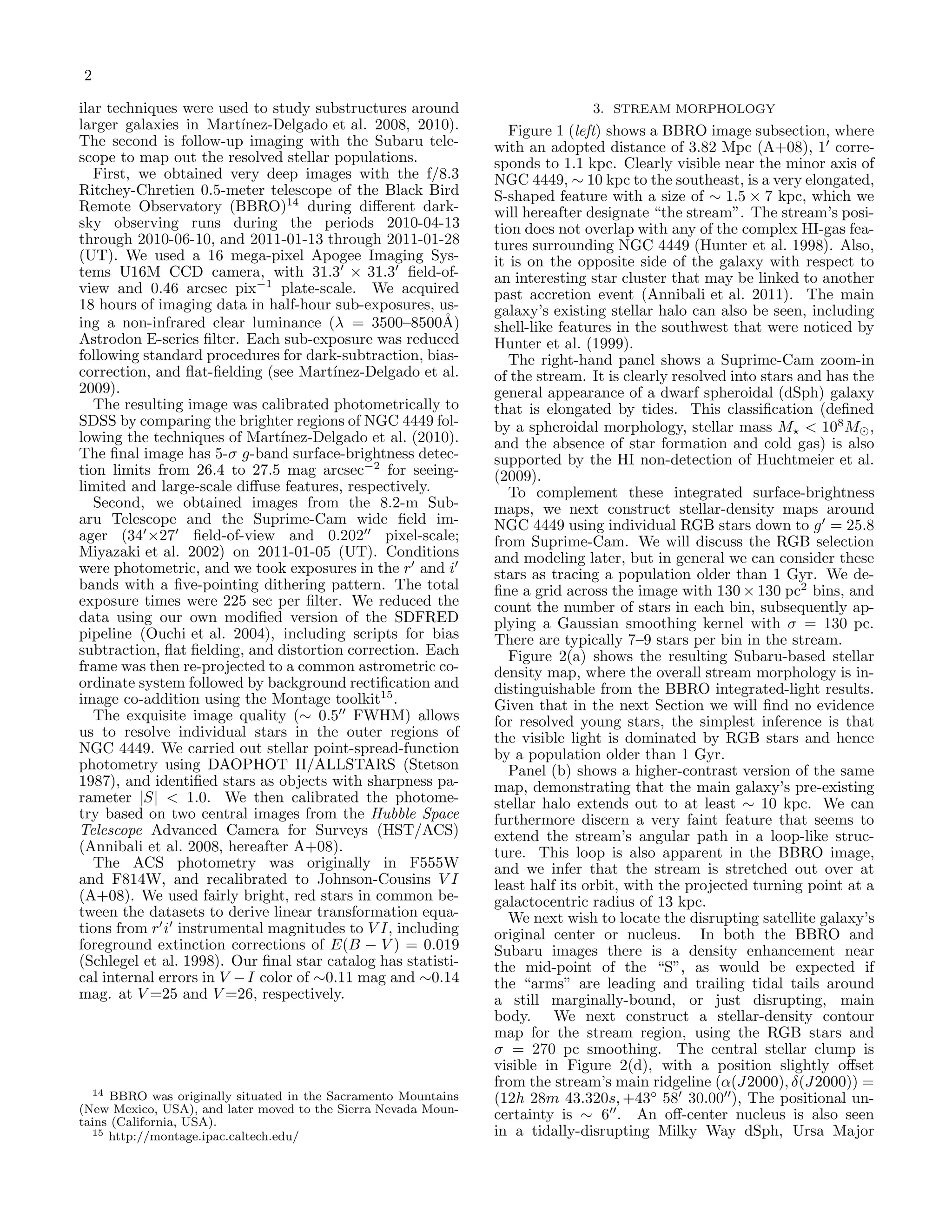

Figure 3 shows the color-magnitude diagram (CMD) tematic color uncertainties are 0.1 mag). Presumably

for point sources in the stream region. The RGB a 10 Gyr model with Z ∼ 0.002 would also be consistent

stars are the dominant feature, along with a few with the data, while perhaps providing a better match

brighter, redder stars that may be oxygen- or carbon-rich to the observed CMD slope. We thus find the stream

thermally-pulsating asymptotic giant branch stars from to have an intermediate-to-old age (∼ 2–10 Gyr) and a

an intermediate-age or old population (Marigo et al. metallicity of [Z/H] ∼ −0.9 to −0.6.

2003). There are no blue stars evident that would trace These results are comparable to the RGB analysis

recent star formation. of the main body of NGC 4449 by A+08 (their fig-

The detection of the tip of the RGB (TRGB) permits ure 17; see also Ry´ et al. 2011). Therefore both the main

s

a distance estimate for the stream. We use the same ap- galaxy and the stream contain similar old, intermediate-

proach described in A+08 and Cioni et al. (2000), and metallicity populations, although the main galaxy also

find a TRGB magnitude of ITRGB = 24.06 ± 0.04 (ran- contains very young stars, as well as more metal-poor

dom) ±0.08 (systematic). The random error was esti- stars as inferred from its globular clusters (Strader et al.

mated using bootstrapping techniques; the systematic 2011).

error is dominated by the magnitude transformation un- It is outside the scope of this Letter to investigate

certainties. The main body of NGC 4449 was found by spatial stellar population variations in the stream and

A+08 to have ITRGB = 24.00 ± 0.01 (random) ±0.04 surrounding regions in detail, but we provide a basic

(systematic). Thus the stream is at the same distance overview by splitting the RGBs into color-based sub-

as the main body, to within ∼ 180 kpc, and we conclude populations, using the 4 Gyr, Z = 0.004 model as a

that there is a physical association rather than a chance boundary. We then create stellar density maps as be-

superposition. fore, for the two subpopulations separately. Using blue

The RGB photometry can also constrain the stream and green color-coding to represent the subpopulations

age and metallicity, despite some age-metallicity degen- left and right of the model boundary, we show the results

eracy. In Figure 3 we overplot the Padua isochrones in Figure 2(c). The stream’s bright parts have no visible

(Girardi et al. 2002) for ages of 2, 4, and 10 Gyr, for](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/dwarfsgobblingdwarfs-120126010833-phpapp01/75/Dwarfs-gobbling-dwarfs-3-2048.jpg)