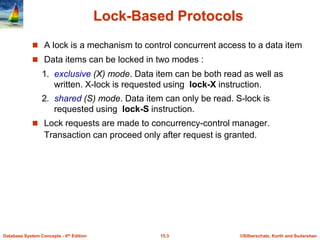

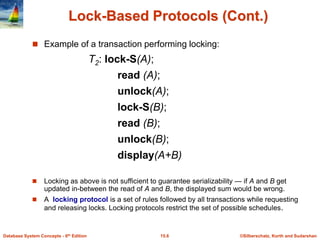

The document discusses various concurrency control techniques for database systems, including lock-based protocols, timestamp-based protocols, validation-based protocols, and multiversion schemes. Lock-based protocols use exclusive and shared locks to control concurrent access to data. Timestamp-based protocols assign timestamps to transactions and ensure timestamp order for conflicting operations. Validation-based protocols execute transactions optimistically and validate their results during a validation phase. Multiversion schemes increase concurrency by keeping multiple versions of data items.