This document describes a student project to develop a prototype file transfer application called Chuck that uses QR codes. The project aims to address the need for easy file transfers between multiple devices. The document outlines the design and development process, including interaction design, technical design of the transmission schema and application, prototype assessment through user testing, iteration of the prototype based on feedback, and evaluation of the effectiveness and future work. Key aspects of the project include creating mockups, building an Android prototype, evaluating it with participants, and improving the prototype based on results.

![Chuck: QR Code File Transfers 1 INTRODUCTION

1 Introduction

This report presents the process by which a prototype for a file transfer application was created and improved.

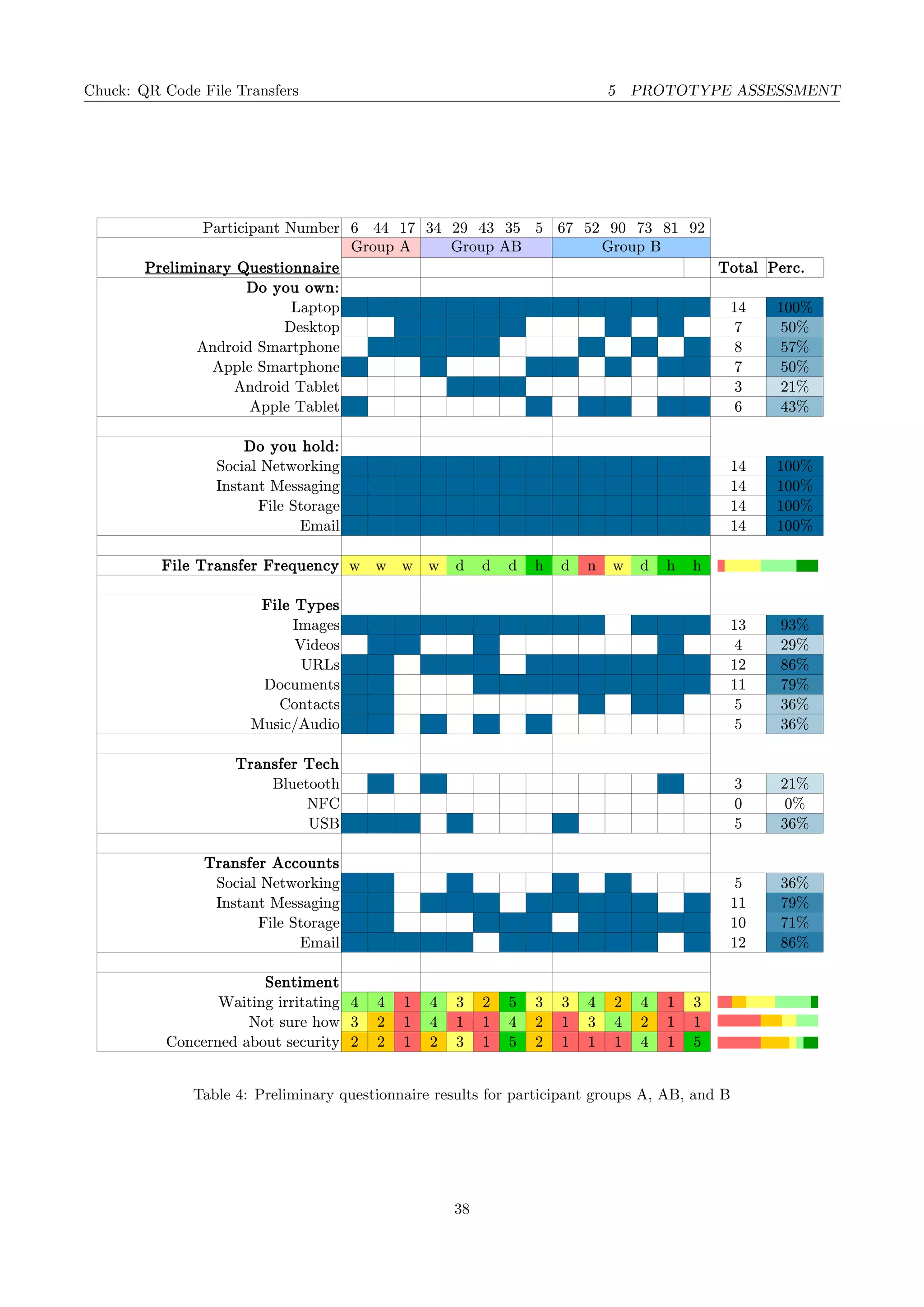

It documents the design, implementation, and evaluation of a prototype application, as well as a series of

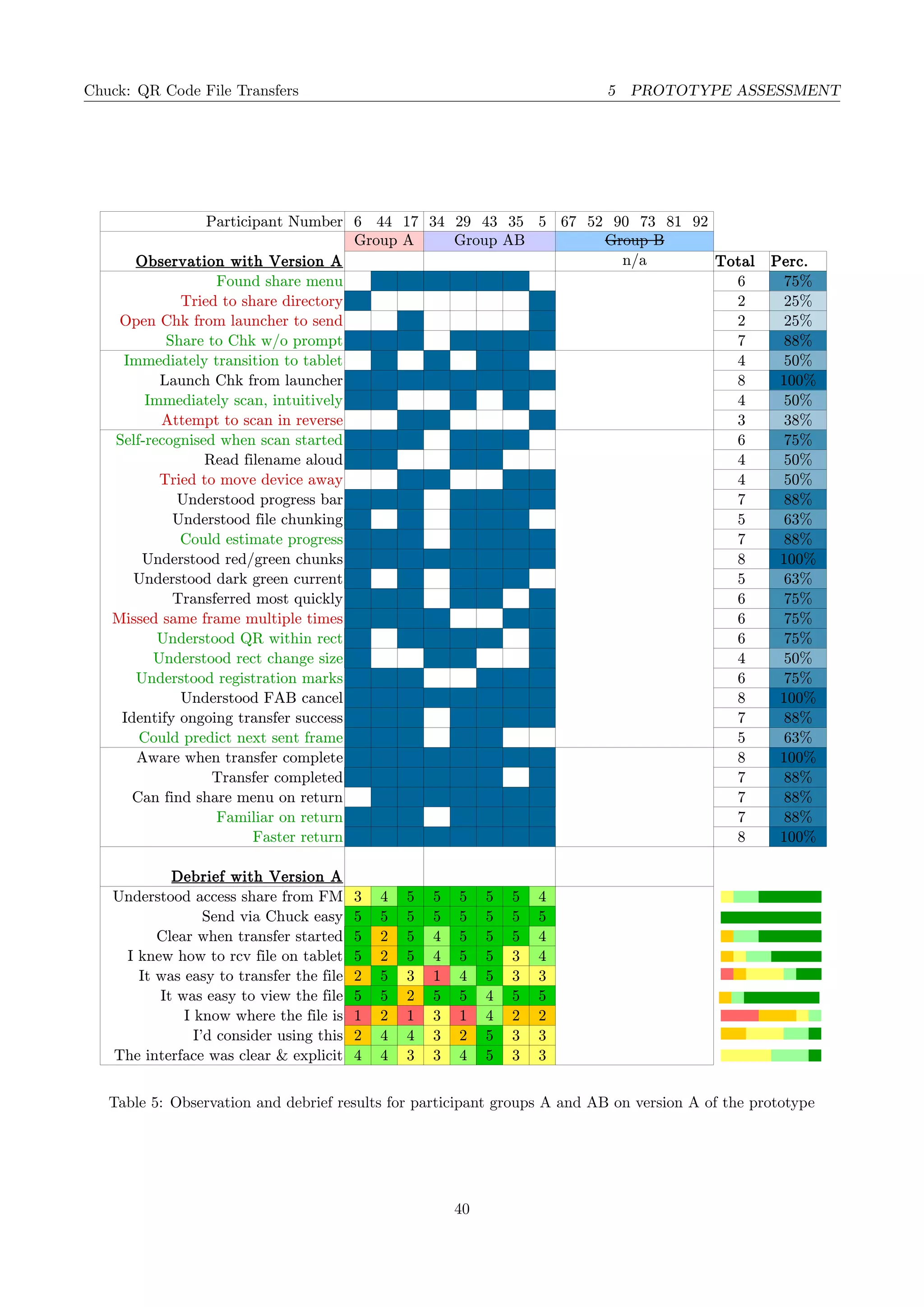

improvements and the effects of these on respondents.

For the avoidance of doubt, the terms application, prototype, app, and Chuck are used interchangeably to refer

to the deliverable for this project.

1.1 Problem description

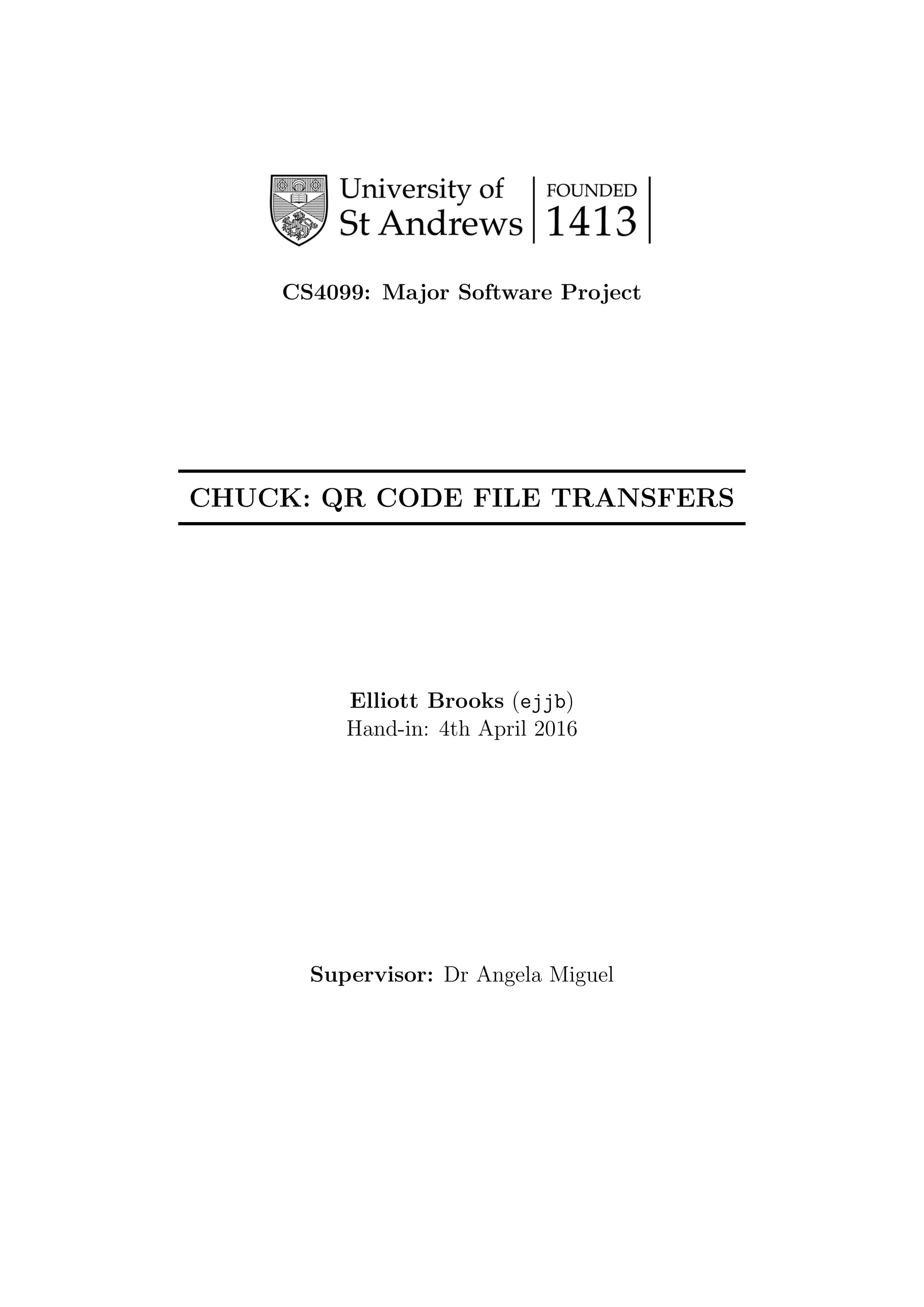

Modern consumers are more likely than ever before to own multiple devices, as shown in Figure 1, resulting

in fragmentation of files and settings across devices. This fragmentation effect can be confusing to users when

files aren’t available on the device currently in use[2], and as such the popularity of file transfer mechanisms are

increasing, with a variety of solutions available [3, 4, 5]. These existing solutions are discussed in more detail in

Section 1.2.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

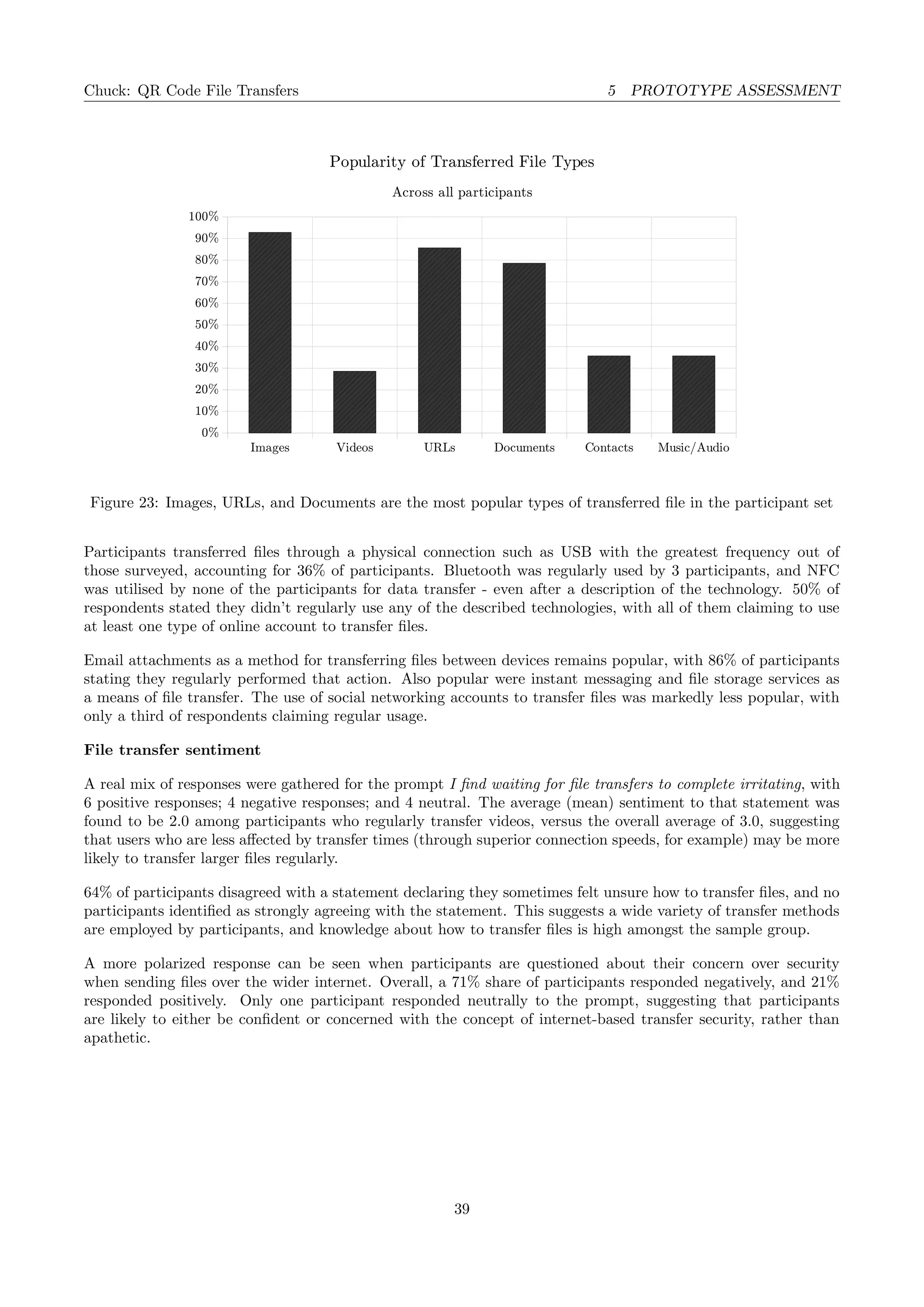

90

May-04 May-05 May-06 May-07 May-08 May-09 May-10 May-11 May-12 May-13 May-14 May-15

Device Ownership by Type

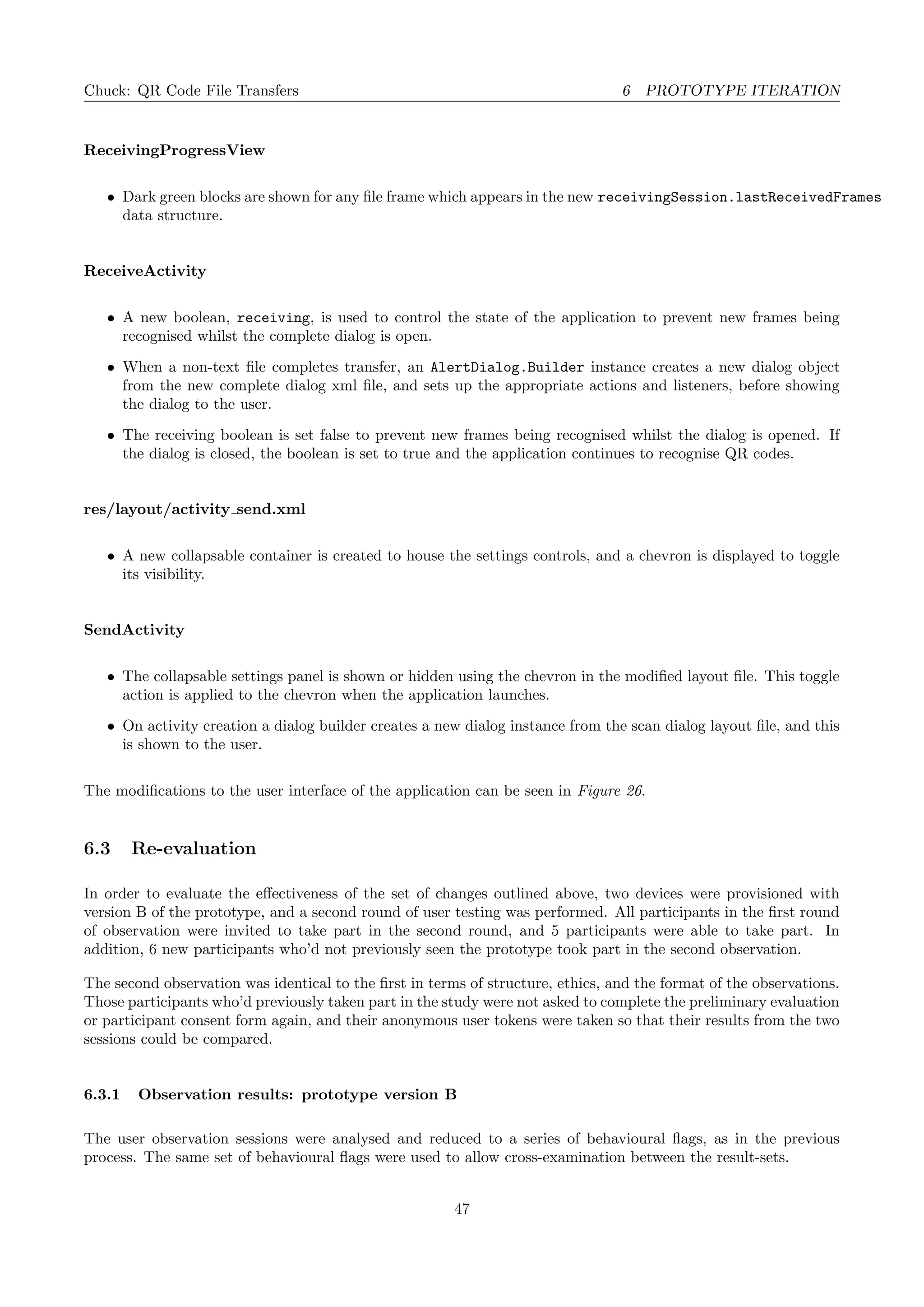

Smartphone eBook Reader Tablet Computer Desktop/Laptop Mp3 Player Game Console

Figure 1: US adult device ownership for various device types[1]. Missing values are interpolated.

Internet-enabled solutions are more popular than ever, with consumers making use of a variety of technologies

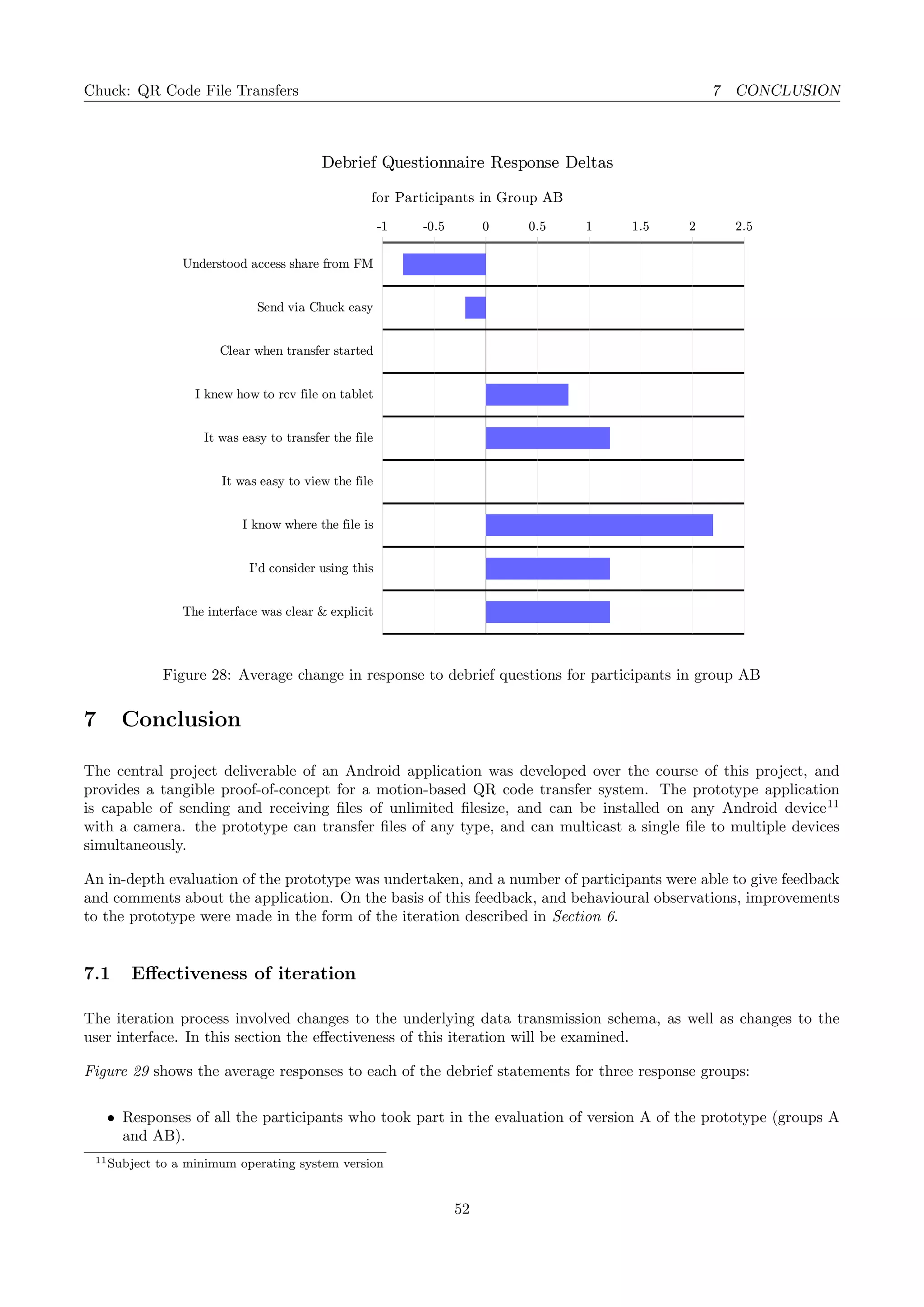

and services to transfer files both at home and at work[6]. The increased popularity in transfer mechanisms can

be largely categorised into two groups of solutions:

Casual transfers

Single-time transactional transfers with the explicit instruction of moving a file between two devices. These

transfers are usually time-sensitive and are explicitly supervised by the end-user(s). Examples include

Bluetooth file transfers and Shared links generated from file synchronisation services like Dropbox.

4](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/827d5c14-a857-456c-a57a-aad576e3a721-160405153539/75/CS4099Report-4-2048.jpg)

![Chuck: QR Code File Transfers 1 INTRODUCTION

Structured transfers

These transfers tend to be longer-lasting continuous synchronisation operations between two (or more)

locations. More time is spent in the investment of setup of these relationships, but the transfer process

itself is usually a background process with no direct interaction from the user. Examples include Dropbox

and Google Drive.

Significant improvements in the quality and feature-set of services exhibiting the latter model have been made

recently, with user numbers of file synchronisation services in the hundreds of millions [7]. However, many of the

transactional file transfers that users perform daily[6] occur through systems where file transfers are a secondary

functionality - for example Social Networks and Instant Messaging applications [8, 9]. Some common pain points

that users experience when making transactional file transfers are:

• Complexity in instantiating the transfer For example pairing devices, sending a URL between devices.

• Knowledge of the saved location of a file

• Latency and lack of speed in transfer

1.2 Similar systems

In this section existing systems which attempt to provide support for users partaking in file transfer operations

are explored.

1.2.1 Dropbox [3]

Dropbox

LAN

C1 C2 C3

Figure 2: Propagation of

a change within Dropbox

from Client 1 to {2,3}

Dropbox provide a proprietary set of desktop clients allowing users to

synchronise a folder of files across multiple devices. This core offering is able

to implicitly detect changes in the files within the set of files and synchronise

changes between other devices according to the modification date of the file.

This process is entirely automated, and once setup requires no input from the

user 1

Figure 2 shows how a central source of truth is maintained in the form of the

Dropbox server. Changes to files on a single machine must be propagated to

the central service before these changes are relayed to other clients.

Files that have been synchronised to the central data-store can be shared via

uniquely-generated links by the user. This process can be used to instantiate a

transactional transfer with another device or user, by sharing the URL of the

file. These file addresses are temporary, and can be revoked by the user.

In addition to the desktop clients, there are mobile applications that provide

transactional access to the set of files stored within Dropbox’s servers for a particular user. This access

includes the ability to upload or modify files, although no direct synchronisation functionality is available at

present. Automatic uploading of photographs and videos on smartphones is available, however, which mimics a

one-directional synchronisation process.

Dropbox also provide a basic file versioning service, where ‘previous versions’ of files are stored and users are able

to rollback changes that have been made. No diff functionality is provided, so users perform restore actions on

the basis of modification timecodes.

1Except in cases where a modification conflict is detected, where user input is required to choose a version to keep.

5](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/827d5c14-a857-456c-a57a-aad576e3a721-160405153539/75/CS4099Report-5-2048.jpg)

![Chuck: QR Code File Transfers 1 INTRODUCTION

Pricing

Dropbox’s model is priced according to storage space, with a free tier of 2GB2

and several premium tiers with a

more generous allowance aimed at both personal and business usage. This storage quota includes the overhead

of the versioning solution, such that versioning capabilities are diminished as the limit is reached.

LAN

C1 C2

C3

Figure 3: Propagation

of a change within

Bittorrent Sync from

Client 1 to {2,3}

Derivative systems

Google Drive (http://google.com/drive)

has a similar desktop client and mobile application, providing users with an

increased amount of space for free (15GB). Has similar transactional sharing,

URL generation, and has photo uploading through the companion application

Google Photos.

Bittorrent Sync (https://www.getsync.com)

makes use of the Bittorrent protocol for file transfers, and doesn’t rely on

a centralised server to propagate changes. Users are able to create local

synchronised folders and distribute read/write keys to other clients which

allow synchronisation through the Bittorrent network. In cases where a direct

connection is not possible (through NAT (Network Address Translation) or

port filtering) a relay server is used. Figure 3 shows how this design leverages

network topology to improve transfer times, with nodes within the same LAN

(Local Area Network).

1.2.2 Wetransfer [4]

Wetransfer is an online service allowing users to generate one-time URLs to share large files over the internet -

all from within the browser. Unlike Dropbox’s model, this service is aimed more at ad-hoc file transfers from

user-to-user (or a single user performing a device-to-device transfer).

The user starts by creating a new session on the website and uploading a large file (up to 2GB for a free account,

up to 20GB for premium accounts[4]). A unique URL is generated once the file has been uploaded, and this

permits the download of the file from another device. Like the upload process, the download process is explicit

and in-browser. The browser-based upload and download model helps secure a high platform coverage, and

creates a low friction to transfer initiation.

Downsides in this model include the sequential nature in which the transfer is approached; in three distinct and

siloed stages:

• Initial upload of the file to be shared

• Generation and transmission of the URL

• Download of the file

Performance analysis of Wetransfer transfer model

The first and last of these stages are likely to be the most time-consuming, and the duplication of transfer process

would make the total transfer time T ∝ (Ga + Gb) × F where:

Gi represents the goodput between the centralised server and client i ∈ {a, b}

F represents the size of the file under transfer

2Users can earn additional space through a referral programme

6](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/827d5c14-a857-456c-a57a-aad576e3a721-160405153539/75/CS4099Report-6-2048.jpg)

![Chuck: QR Code File Transfers 1 INTRODUCTION

1.2.3 Bluetooth [5]

Bluetooth transfer technology allows users to pair devices and initiate transfers. These transfers are strictly

unicast as Bluetooth is a round-robin protocol, and the pairing process must be completed before a transfer

begins (making this process less suitable for an ad-hoc transactional file transfer).

Pairing process

The intricacies of the pairing process are dependant on which of three security modes the device is configured

for. To generalise:[10]:

• Mode 1 offers no encryption or security during the pairing process and subsequent transfers over the WPAN

• In Mode 2 encryption and authorisation measures are in place once the pairing process is complete and a

communication channel has opened.

• Mode 3 enforces security and encryption at the link layer, ensuring that the connection process itself is also

secured.

The pairing process involves the exchanging of randomly generated values, physical addresses, and derived keys.

This process often takes several seconds, and involves explicit interaction from the user (confirming or entering a

PIN, or allowing a pairing event to occur). Once two devices are paired connections can be spontaneously made

between the devices in the future (that is to say receiving devices are ‘remembered’ by the sending device and

vice versa).

Figure 4: An Android

device displaying the share

menu.

Transfer process

For mobile devices, file transfers over Bluetooth are usually initiated from a file

manager application or a media viewer. The user is able to begin the process

of transferring the file (or, if necessary the pairing process) from within the

application itself. Within the Android operating system, this is referred to as

firing an intent[11].

Figure 4 shows the screen presented to users once a file has been selected for

sharing on an Android device. Multiple applications are visible, all of which

have registered with the OS as being able to handle the share intent. Filters

can be placed on these handling declarations (for example to only include video

files), and they’re made in the application manifest.

Once the Bluetooth option has been selected, the user is prompted to select

a previously-paired Bluetooth device within range. If no such devices are

available the user is able to create a new pairing. Once a device is selected

a request to send the file (which must be accepted by the receiving party3

) is

made, and the transfer can begin. From this point onwards the transfer process

is more implicit, and users are able to place the devices into standby mode. An

important stipulation is that devices must remain within Bluetooth range (the

range of which is dependent on device model, but is usually of the order of 10

metres).

3Some operating systems contain functionality to auto-accept file transfers over Bluetooth

7](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/827d5c14-a857-456c-a57a-aad576e3a721-160405153539/75/CS4099Report-7-2048.jpg)

![Chuck: QR Code File Transfers 1 INTRODUCTION

1.3 Concept

The technologies discussed in Section 1.2 cater well for structured transfers, where some significant time is

available to set up the transfer parameters, and for transactional transfers where a relationship between two

devices is already established. This report presents a solution for ad-hoc transactional file transfers between

devices in close physical proximity, based on the QR code standard.

1.3.1 QR codes

QR codes were created by Denso Wave[12], and accepted as an ISO standard (ISO/IEC18004) in June 2000. The

technology was originally developed as a method for tracking inventory within manufacturing lines, as each code

could store an increased amount of entropy versus a standard barcode. QR codes have multiple features that

contribute to their popularity as a means of transferring data visually:

Redundancy

Generated codes can contain anywhere from 7% to 30% redundancy, dependant on the level of error-correction

specified at the encoding stage. This is accomplished through the application of Reed-Solomon error-correction

codes[13], which are also used in the encoding of CD audio data.

Variable length

Payloads of varying length can be successfully encoded into QR codes, up to a maximum defined by the

resolution of the outputted code, the type of code being generated, and the level of redundancy.

No orientation

Unlike standard barcodes, QR codes have no fixed orientation, so detection of the registration points

requires a planar scanning device. This means the minimum hardware required to scan QR codes is more

sophisticated, but there are therefore no orientation issues during data transfer (Barcode scanners must be

orientated perpendicular to the barcode print direction to be successfully recognised).

With the rise of smartphone technology and the common inclusion of at least one camera in many of these

devices, more consumers than ever are in possession of planar scanning devices. As such, the use of QR codes

to convey short pieces of textual information to users is increasingly common. URLs are commonly conveyed to

users from print media in this form, as shown in Figure 5.

1.3.2 Temporal element

Rather than scanning an individual QR code, it’s possible to scan multiple QR codes per second, in-line with

the speed of:

• The refresh rate on the sending device screen

• The refresh rate on the receiving device camera

• The processing speed of the QR code recognition algorithm on the receiving device.

This approach circumvents the explicit payload size length within the QR code schema, and allows larger payloads

to be transferred without the use of an internet resource.

8](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/827d5c14-a857-456c-a57a-aad576e3a721-160405153539/75/CS4099Report-8-2048.jpg)

![Chuck: QR Code File Transfers 1 INTRODUCTION

Figure 5: A visitor scans a QR code at Hamburg museum [14]

1.3.3 Properties

The main properties of the proposed technology are:

• No reliance on transportation mediums other than visible light, including mobile data, Wi-Fi, and Bluetooth.

• No theoretical maximum file-size

• Supports multicast transfers

• No pre-existing relationship between devices required

• No information about the sending device is known

• Ticketing applications: harder to forge/copy than static barcodes.

1.4 Similar works

This project draws on a number of similar projects and papers, which are referenced throughout this document.

In particular, a piece of work[15] by Haoxuan Wang (Supervised by Dr Ioannis Patras at School of EECS, Queen

Mary University of London) presents a similar concept of using a sequence of static QR codes to deliver a large

payload. This work includes a video[16] demonstrating the system, in which a transfer from a Java desktop

application to a mobile device is shown. In addition, an interim report[17] details a transmission schema.

This project will detail a separate transmission schema and explore additional concepts such as redundancy of

data transferred, and will examine the design and implementation of a more user-centric Android user interface.

9](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/827d5c14-a857-456c-a57a-aad576e3a721-160405153539/75/CS4099Report-9-2048.jpg)

![Chuck: QR Code File Transfers 1 INTRODUCTION

• Is the user able to understand the (relatively complex) transmission process through the interface (or a

simplified version)?

• Does the design adhere to the context of the user’s actions?

• Is the transfer process as frictionless as possible?

This aspect of the project will also begin with the generation of a series of mock-up images depicting the planned

user interface. These will be constructed using background research into similar interfaces, and platform design

guidelines. These are presented in Section 3.5.

The key user stories that will be evaluated against throughout the project are:

• As a user, I want to transfer a file from my device to another device I own.

• As a user, I want to transfer a file from my device to another user’s device.

• As a user, I want to receive a file from another user’s device.

1.6 Deliverables

The project has a single main deliverable, an Android application that provides a prototype for the concept

discussed in Section 1.3.

1.6.1 Android prototype

This prototype will be able to perform file transfers - the same application can operate in transmitting and

receiving mode. This application can be installed on a multitude of devices to test transfer functionality.

The application will be written using the Android Development SDK and will be suitable for installation onto

devices with a minimum Android version of 5.0 Lollipop (SDK version 21). The application will make use of

Android intents to be available from the share menu within file management applications.

1.7 Resources and technology

The following resources will be utilised to produce the application prototype:

• An OSX 10.10.5 development machine

• Android Studio 2.0 Preview 4

• JRE 1.6

• Android Development SDK 5.0.1 (API Level 21)

• ZXing QR code library[18]

And the following resources were provided by the University of St Andrews School of Computer Science:

• A Nexus 4 device running Android 5.1.1

• A Nexus 7 device running Android 5.1.1

11](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/827d5c14-a857-456c-a57a-aad576e3a721-160405153539/75/CS4099Report-11-2048.jpg)

![Chuck: QR Code File Transfers 2 PROJECT AIMS

2 Project aims

In order to provide a clear and demonstrable focus for the project, the high-level objectives discussed earlier in

this document are here formalised into a series of primary, secondary, and tertiary aims. Not all of the objectives

discussed here are expected to be completed as part of the project, but identification of stretch goals before the

project begins allows the project to develop in unexpected ways.

Similarly, the project will retain agility throughout the development process, and the priorities and deliverables

may vary throughout the lifetime of the project to present the concept in the best way.

2.1 Primary

Android Application

Delivery of an Android Application that allows users to transfer files between handsets. Able to transfer

small files (eg. text files) in a modest transfer window (several seconds).

Debug Information

Ability to monitor the progress of a transfer and other related information from a debug console, either as

part of the application itself or a separate console.

Polyfill Ability

The application is able to recover from a missing frame event by waiting for the offending frame to appear

again from the transmitter.

User Satisfaction: Convenience

Users report in feedback sessions that they find this method of transferring data convenient - perhaps more

convenient than traditional methods such as Bluetooth

2.2 Secondary

Automated Usage Monitoring

Making use of MixPanel [19] or a similar service, anonymous monitoring of user behaviour whilst interacting

with the application. This could complement more intense qualitative assessment methods of user interaction.

Integration with OS

The Android Application is able to be triggered from the ”share menu” present in Android, by registering

the proper Intent with the Operating System.

Modest-sized File Transfers

The application is able to process transfers of moderately sized files (such as photographs and short music

clips/ringtones) within an appreciable transfer window (<30 seconds)

Virality of Application

Through a viral feature, it’s possible to onboard new users through existing QR code applications, by

directing them to a website to download the application and complete the transfer.

User Satisfaction: Transfer Speed

Users report in feedback that file transfers occur in an acceptable timeframe, and quantiative analysis

supports this.

Analytics: Low level of Transfer Abandonment

Analytics are able to demonstrate a low level of transfers started but not finished.

12](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/827d5c14-a857-456c-a57a-aad576e3a721-160405153539/75/CS4099Report-12-2048.jpg)

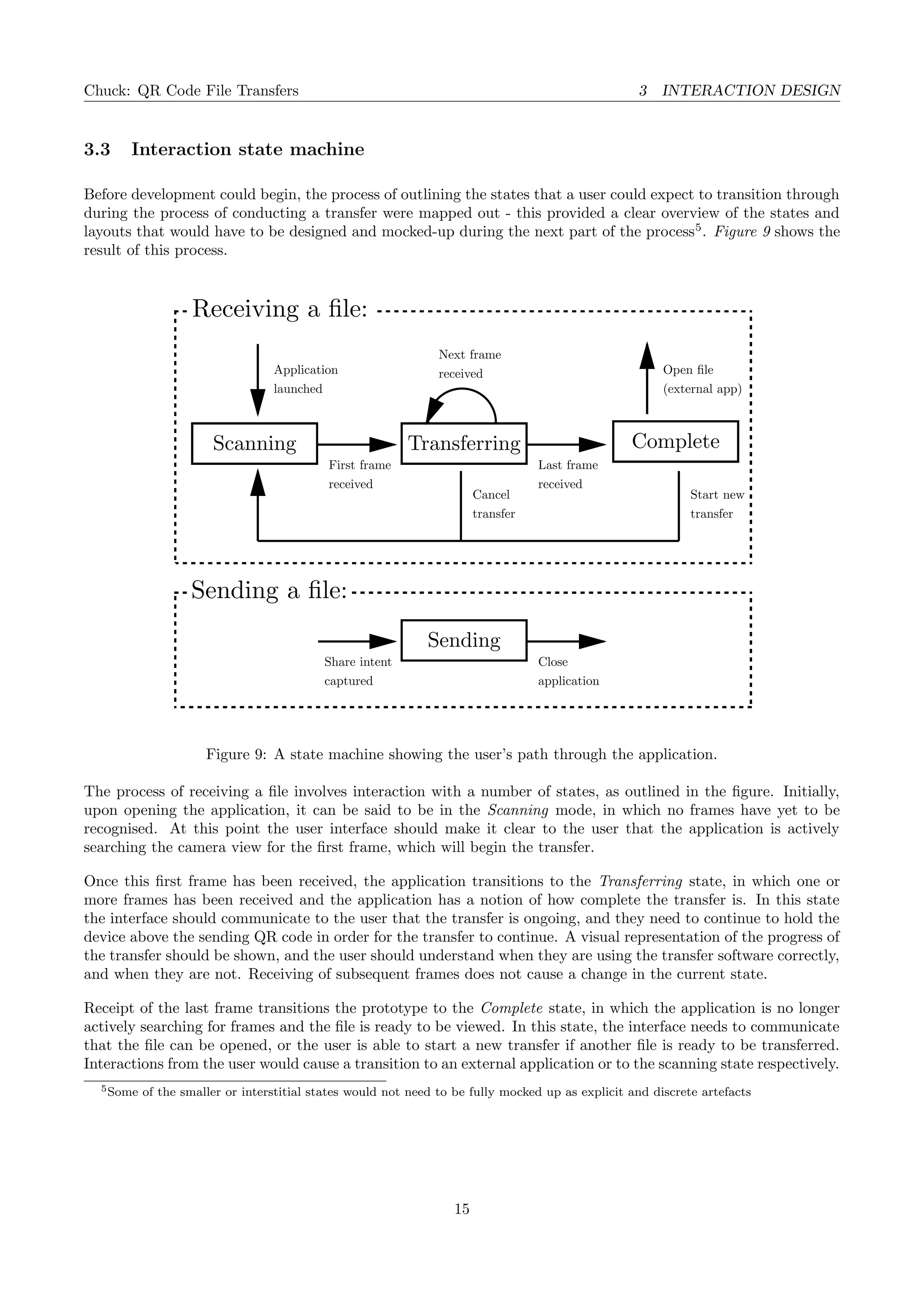

![Chuck: QR Code File Transfers 3 INTERACTION DESIGN

3 Interaction design

An important part of the prototype design phase of this project was the formulation of a robust and intuitive

design that demonstrated the core project concept. As such, a basic design was outlined before development

started and an iterative design process occurred during development.

3.1 UI and UX considerations

As discussed in Section 1.5.2, the design must fulfil the central requirements of being intuitive and communicative.

Users are likely to be familiar with the process of scanning a single static QR code, but the idea of holding the

device in place for a period of time to scan subsequent frames might prove to be difficult to communicate.

More strictly in terms of interface, an attempt to encourage user intuition was made through compliance with

Android design guidelines. More specifically, the Material Design[20] specification was used as the basis for many

of the macro design decisions that were made. Several components, including the FAB (Floating Action Button),

were used wholesale from this set of guidelines as a means of improving the familiarity Android users would have

with the interface.

3.2 Branding and colours

In order to present an accurate proof-of-concept for how users may interact with the system, it was important to

create a valid visual identity - this would facilitate user recognition during the later assessment stages, and help

to ensure that users would be able to continue a session in the prototype from one device to another.

As the prototype application was only being developed for the Android platform, it was decided to adhere to

Google’s Material guidelines regarding application icon design, and a bold red/orange primary colour was chosen

as the base branding colour, shown in Figure 6. This figure also shows a secondary accent colour that was

identified, and darker variants.

Accent AccentPrimary

Dark

Primary Accent

Dark

Figure 6: Primary and accent colour swatches chosen

for the prototype branding

Figure 7: A full render of the logo used for the

prototype

Figure 8: Application logo for the prototype, seen in

the launcher and Android intent share menu.

Following on from this initial colour palette, a visual identity was constructed from the prototype, themed on

the concept of movement. In a similar vein, the name Chuck was chosen to represent the off-handing of files in

an ad-hoc manner during a file transfer. A logotype was constructed, and a variation for the Android prototype

launcher icon was created, shown in Figures 7 and 8 respectively. These visual elements were designed with the

express purpose of being memorable and visually striking, to aid user recall during the transfer process as their

session transferred from device to device.

14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/827d5c14-a857-456c-a57a-aad576e3a721-160405153539/75/CS4099Report-14-2048.jpg)

![Chuck: QR Code File Transfers 3 INTERACTION DESIGN

3.4 Custom components

As part of the interface development, two key components that would require significant attention in order to

convey transfer success were identified:

3.4.1 Augmented preview

In order to provide the user with sufficient information to receive the file, the receiving interface needs to contain

visual cues to prompt user behaviours. More specifically, the user needs to be guided to maintain a steady fix

on the sending QR code. This is a behaviour that will require explicit instruction as even users familiar with

QR code technology will expect a single successful scan to transfer the entire file. As such the interface should

prompt the user to maintain contact between the devices for the duration of the transfer.

Figure 10: A barcode

scanner displaying a

scanning guide [21]

Figure 11: Registration

point markers and scan

guides.

A common prompt in these kind of ’scanning’ application is the augmentation

of the camera preview with one or more guide marks which establishes an

expected geometry for the code, and provides a mark for the user to aim for.

These kinds of marks are well-suited to this application, as it will prompt the

user to continuously keep the constantly-changing code in view of the receiving

device. A physical manifestation of these guide marks can be seen in Figure

10.

In addition to this device, a secondary set of markers representing successful

recognition of a code is a common sight in scanning applications. These

marks provide a binary success feedback for users, rather than attempting

to direct their actions explicitly. By displaying these markers when a frame

has successfully been recognised, users should have an understanding as to

whether a transfer is currently progressing successfully, which should develop

a user’s natural intuition. The aim would be to exploit the effect of the

learning curve, and to help the user develop their skills in using the prototype

through subsequent uses through regular and honest feedback as to transfer

and recognition progress.

Overlaying the live camera preview in the prototype application with these

marks should help to instruct users to perform behaviours likely to result in a

successful transfer. A mockup of these marks can be seen in Figure 11.

3.4.2 Transfer progress

As part of his 10 design commandments, Rams[22] stipulates that good design should be honest about state

and ability. The design for the receiving interface should be honest and clear about the transfer progress, and

care should be taken to ensure that this does not increase complexity for the user when ascertaining the transfer

progress.

The difficulty with this type of transfer centres around the uncertainty about specific frame transfer success, and

that the connection is not duplexed. This means that in the best case6

the transfer time can be calculated as

the number of frames multiplied by the frequency at which a new frame is shown:

Ttotal = |frames| × fnextframe

However, it is possible that at least one frame will not be correctly received. Frames can fail to be recognised for

a variety of reasons:

6in which all frames are recognised

16](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/827d5c14-a857-456c-a57a-aad576e3a721-160405153539/75/CS4099Report-16-2048.jpg)

![Chuck: QR Code File Transfers 3 INTERACTION DESIGN

• Temporary specular reflections or other temporary optical artefacts preventing successful recognition

• User behaviour: failing to keep QR code within search area for the duration of the transfer

• Temporary lapses in camera focus caused by autofocus functionality or similar being triggered by previous

frames

• Previous frames of a differing size altering the search area to be smaller than required

Figure 12: Differing

received frame profiles can

affect remaining transfer

time.

Figure 13: The Vuse torrent

client displays file portions

as blocks [23]

When this occurs, the remaining transfer time can be greatly influenced by the

time at which this error occurred. Take the two examples presented in Figure

12, in which frames that have been successfully transferred are shown in blue.

Both these examples are representations of the current state of transfer in a

system transferring frames in a sequential looping fashion. Both contain three

’missing frames’, in the form of two frames that are yet to be transferred, and

one frame that was (presumably) not recognised. The frequency at which new

frames are introduced is constant, so the remaining transfer time for both of

these examples can be said to be proportional to the number of frames that

must be transferred before the transfer is complete. We can express this as

x × fnextframe

As such, the remaining transfer time in the first example can be said to be

proportional to the time taken to complete the ’first sweep’ of the frames, plus

the time to re-transfer the missing frame. In this specific case this is 2 plus 7,

giving us an x value of 9 frames.

Conversely, the second example requires less frames to be transferred in order

to retransmit the missing frame due to its index within the frames array. As

such the value of x would be 3, 2 plus the 1 extra transfer frame.

This distinction illustrates the difficulty in establishing a reliable link between

remaining transfer time and transfer progress, as both of these examples have

the same notional value of completeness; 0.7. It’s possible to determine the

remaining time according to the metrics discussed here, but a linear progress

bar is not necessarily honest about the transfer progress. As such, a display

that accurately expresses the received progress would be useful, similar to the

displays commonly seen in applications that facilitate modular file downloads,

as seen in Figure 13.

3.5 Mock-ups

As part of the design process for this project, a set of mock-ups were created before development began. These

mock-ups sought to influence interface design decisions that would be made throughout the course of development

and form an initial start-point for design iteration. These mock-ups are presented in relatively high fidelity, but

the underlying design concepts and decisions being explored were very much in the early stages when these were

created, and as such they bear a limited relation to the final prototype.

The following states were mocked up during the first stage of the project:

17](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/827d5c14-a857-456c-a57a-aad576e3a721-160405153539/75/CS4099Report-17-2048.jpg)

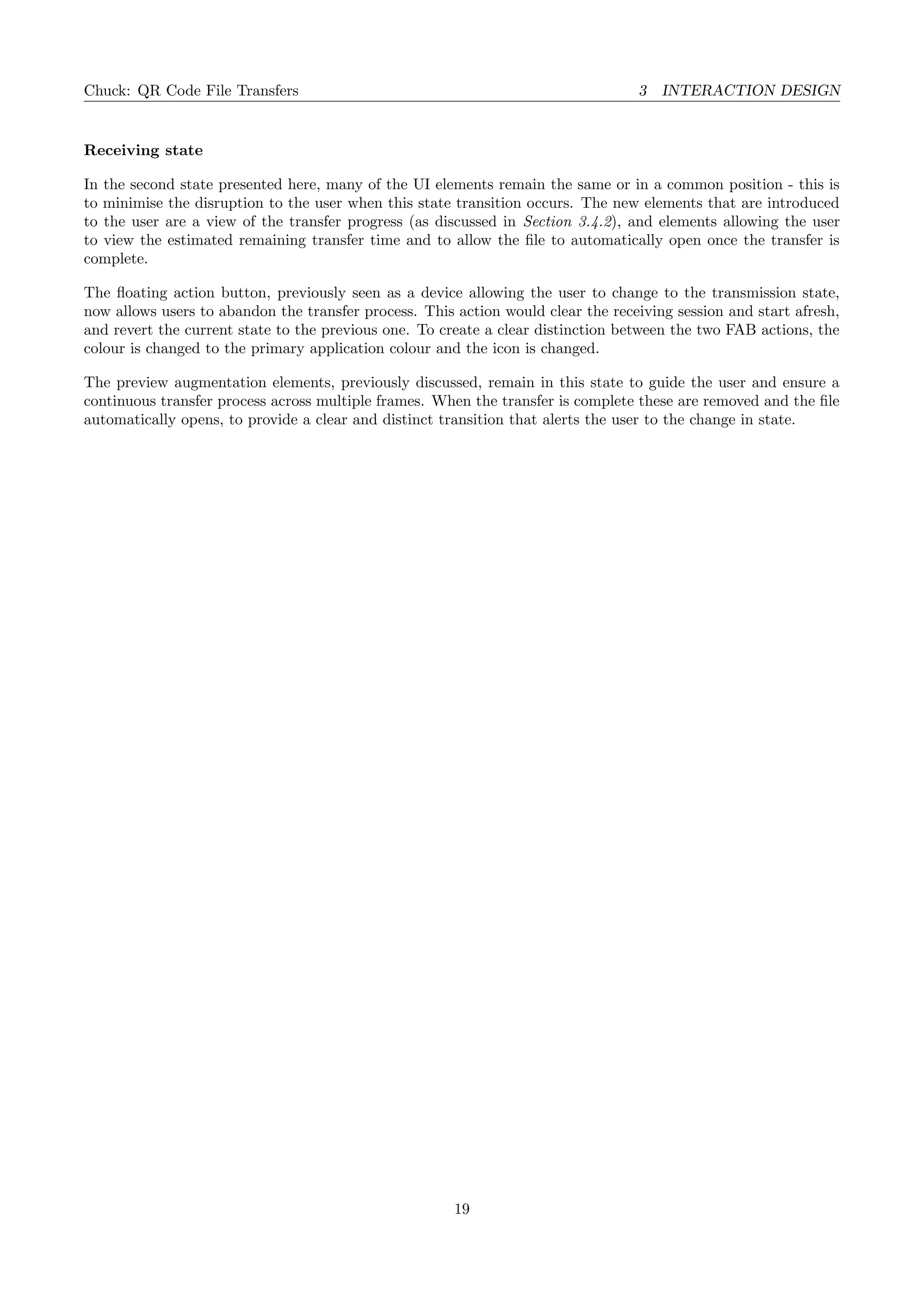

![Chuck: QR Code File Transfers 3 INTERACTION DESIGN

3.5.1 Receiving files

As discussed in the previous state machine, the user interacts with multiple screens throughout the process of

receiving a file, as they transition between states. In Figure 14 two mock-ups are presented, corresponding to

two states the user will interact with during the process.

Centre the code in the guide box to receive

Recieve Files

Hold Steady! Hold Steady!

Hold the code steady in the centre of the guide

Transferring - 72%

Approx 12 seconds remaining

Open when transfer completes

Figure 14: Mock-ups showing the proposed User Interface for both the scanning and transferring states.

Searching state

This mock-up provides a preview of the camera input to the user, with information about the QR code location

overlaid, as discussed in Section 3.4.1. This information helps the user to position the receiving device correctly

with respect to the sending device, and ensures that subsequent frames are received correctly. The registration

points are clearly marked as green icons, making use of the accent colour as a clear contrast to the background.

This accent colour is also used elsewhere in the application as a positive/primary action indicator, helping to

suggest to the user that the presence of these registration marks is an indicator of a successful transfer process.

The bounding area display is used to encourage the user to position the QR code in the centre of the display. As

time progresses the search area slowly increases on the screen, allowing the user to easily position the QR code.

Feedback on the screen informs the user that the prototype is actively searching for the first frame of a file, and

prompts them to place the sending device’s generated QR code in view of the receiving device to receive the file.

A FAB (Floating Action Button[20]) is displayed in this state, allowing users to transition to sending mode (by

selecting a file for transmission). The accent colour is used on this button to show it as a non-negative action,

and the icon suggests an uploading function.

18](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/827d5c14-a857-456c-a57a-aad576e3a721-160405153539/75/CS4099Report-18-2048.jpg)

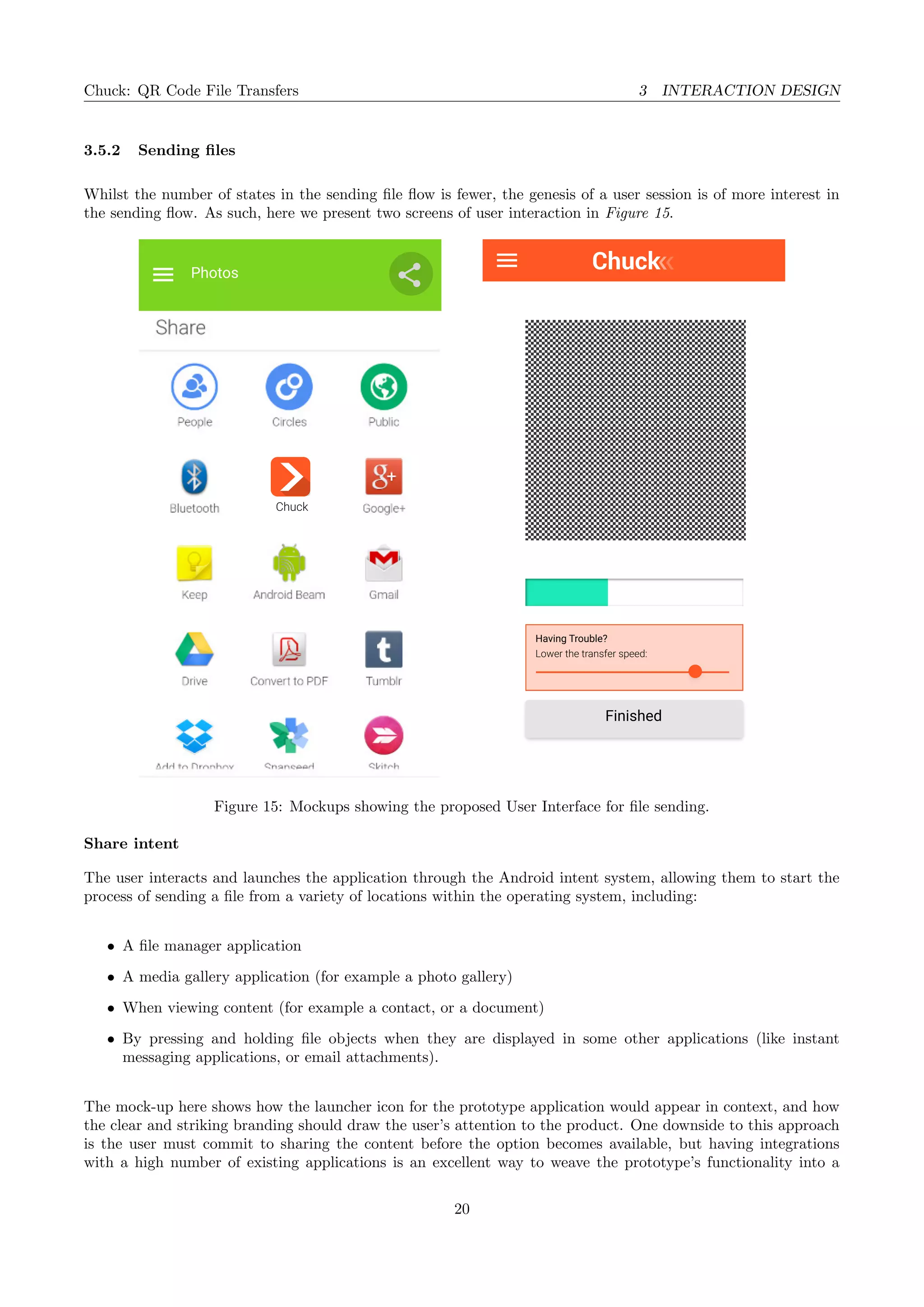

![Chuck: QR Code File Transfers 4 TECHNICAL DESIGN

4.2 Application

Commentary about application and code structure in this section pertains to the first version

of the implementation shown to participants - this version is represented by git commit

7e55ea2ced0dc52e800396f31a9e0e690cb0c0d4 in the submission implementation folder.

This can be accessed via git checkout 7e55ea2ced0dc52e800396f31a9e0e690cb0c0d4 or through the APK

file ImplementationVersionA.apk. More information on sideloading APK files can be found in Appendix A

For the rest of this document this build shall be referred to as version A of the prototype.

The android application itself is comprised of a series of classes to represent objects involved in the transfer

process, activities that the user interacts with, and layout and graphic resources.

4.2.1 Abstract classes

Session

This object represents either a sending or receiving session, and contains fields for storing and retrieving:

• the total number of frames

• the File under transfer

• the type of session

• an array of Frames

4.2.2 Classes

ReceivingSession

Frame[]

Figure 18: Processing

of recognised frames.

Previously-unknown

frames (blue) are

added, duplicated

frames (orange) are

ignored.

This class contains methods for processing a Frame that has been received and adding

it to the underlying frame data structure, as shown in Figure 18. It also has methods

for calculating the file transfer progress, and for determining if a transfer has been

completed. A boolean map of the current transfer status is also calculable from

the getTransferProgressMap method, and is used elsewhere in the application to

display transfer status to the user.

This forms the main data structure the ReceivingActivity interacts with, and is

responsible for reconstructing the received file.

SendingSession

This class contains fields for the frameLength, which defines the length of file

payload within each frame, and bitmapSize which defines the pixel dimensions of

the generated QR code bitmaps.

In addition, the class contains a method generateFrames, which is used once to

populate the frame array with instantiated Frame objects, splitting up the total

payload according to the frameLength value. New frame instances are created with

an appropriate payload start and length values, as shown in Figure 19.

23](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/827d5c14-a857-456c-a57a-aad576e3a721-160405153539/75/CS4099Report-23-2048.jpg)

![Chuck: QR Code File Transfers 4 TECHNICAL DESIGN

payload.length = 26

frameLength = 6

= Frame[]

frames.length = 5 = ceil(payload.length / frameLength)

payloadStart

payloadLength

0 6 12 18

6666

24

2

Figure 19: File chunking algorithm, where a single payload is transformed into an array of Frame objects.

File

This class represents a file under transfer, and is referenced by both sending and receiving sessions. The string

fields type and name are present in both cases, and depending on the type of file, information about the payload

is stored. For short text-based transfers like URLs, the payload is stored directly within the file object as a

string, and for files with longer payloads a payloadUri is stored instead.

An important distinction can be made between text transfers, which have no type, and text file transfers, which

have type text/plain. The former payload is stored in memory, the latter is stored as a Android content URI

to the text file.

The readPayloadSubset allows for the reading of a section of the referenced payload to be returned as a

Base64-encoded string. Conversely, the writePayloadSubset method allows the receiving session to write to

sections of a newly-created file as they are received - this process is assisted by openPayloadWritingSession

and closePayloadWritingSession helper methods.

The getPayloadSize method has relatively complex conditional logic due to the variety of ways in which a file

can be referenced:

• For text transfers with explicit in-object payloads, payload.length provides the required value

• For external Android file URIs, a java.io.File object is created and queried for file length.

• For external Android content URIs, the Android ContentResolver is queried to identify payload length

Frame

The frame class represents an individual transfer frame from payload section through to the generation of the

QR code bitmap. Instances have fields representing the parent session, and the current frame number. Read

and write methods for the payload are provided, calling upon the methods discussed previously within the File

object and for the provided payload start and length values.

Logic to serialize and deserialize this object are included, in the form of the getFullPayload method and

the Frame(String source, Session parentSession) constructor. These methods contain references to the

org.json Java library, and the details of the schema discussed in Section 4.1.

The serialization method is called by generateBitMatrix, which makes use of the ZXing library to construct

a two-dimensional bit matrix. In turn, this method is used within getBitmap, and its result is passed into a

bitmap object and returned.

24](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/827d5c14-a857-456c-a57a-aad576e3a721-160405153539/75/CS4099Report-24-2048.jpg)

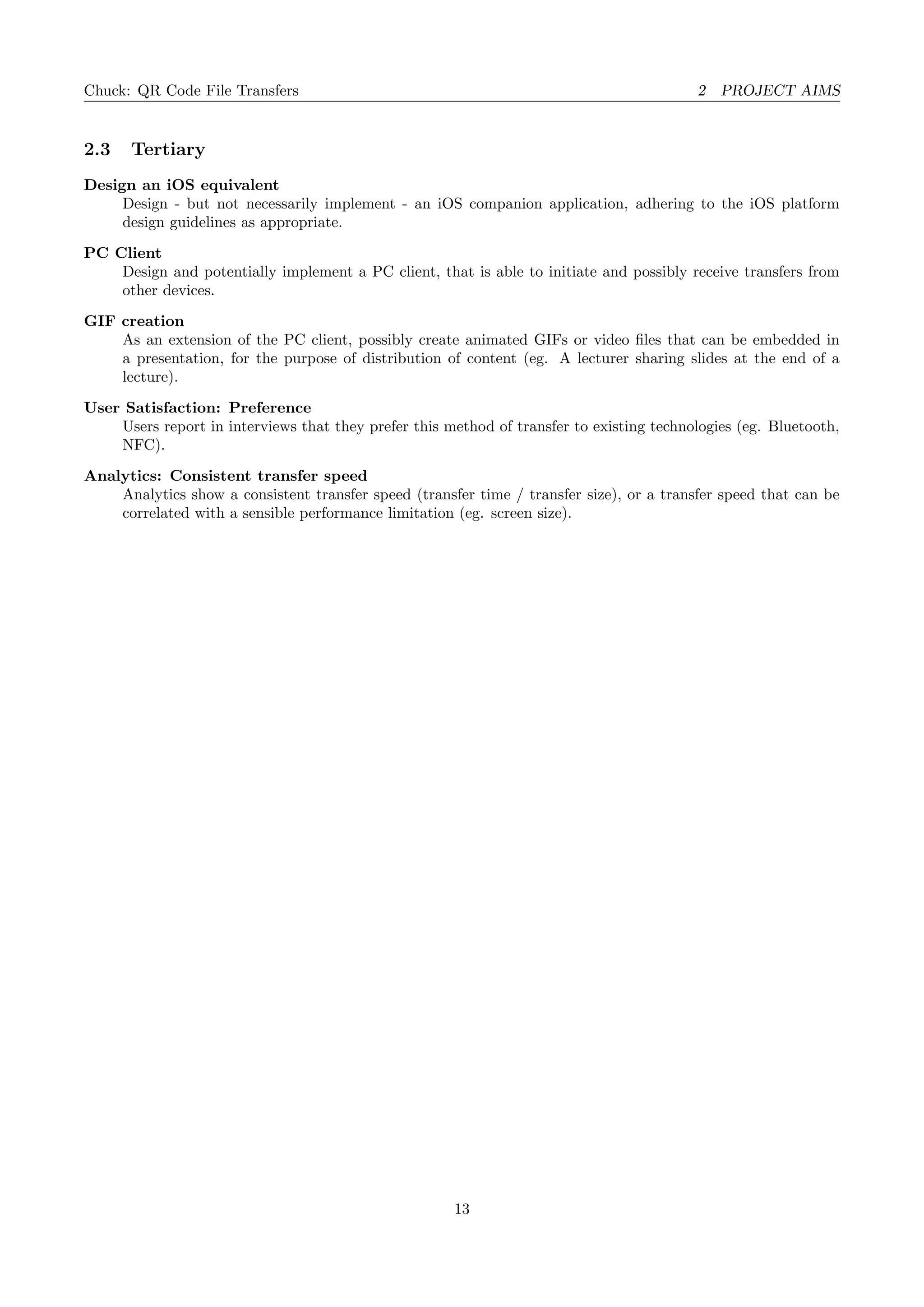

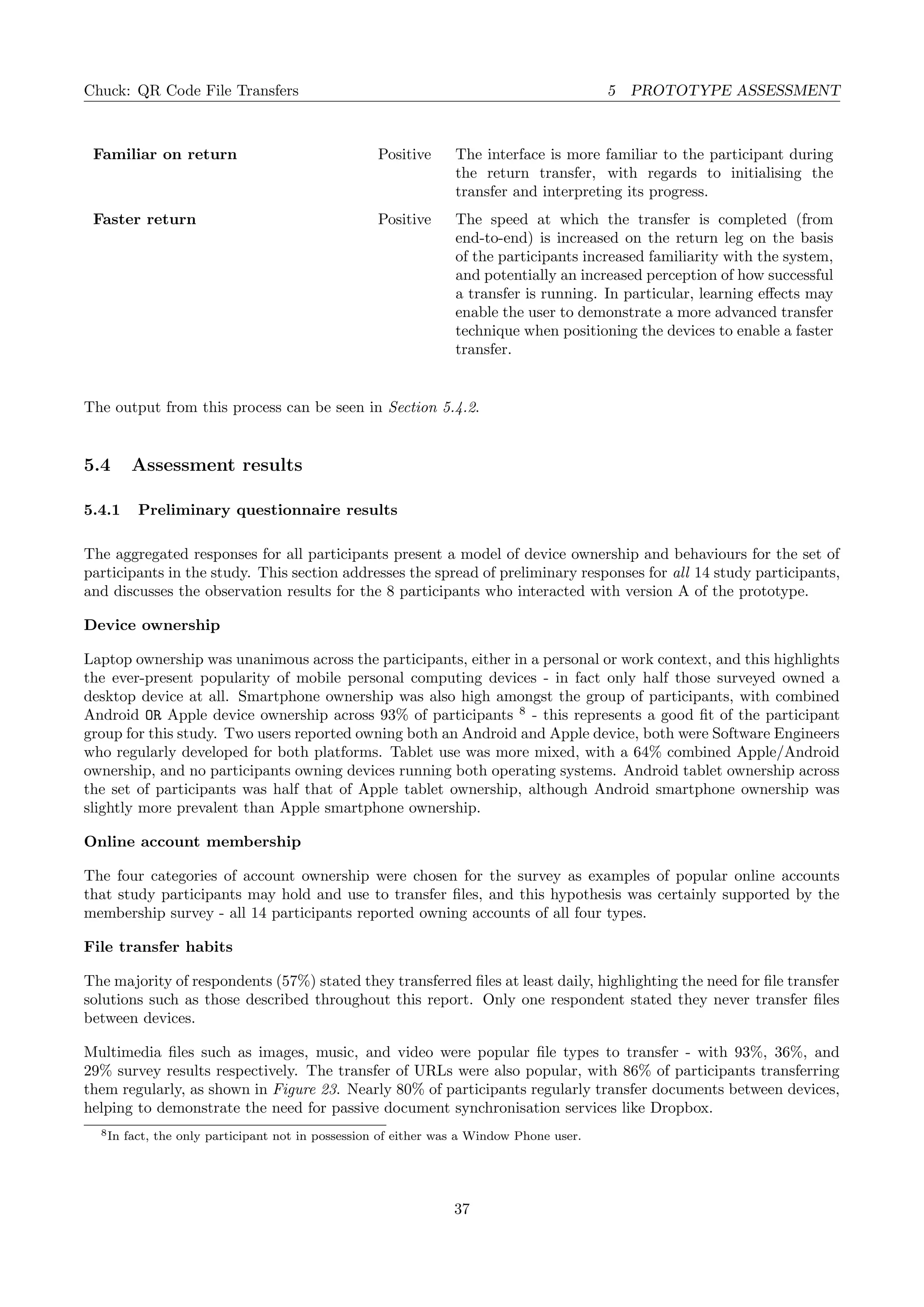

![Chuck: QR Code File Transfers 5 PROTOTYPE ASSESSMENT

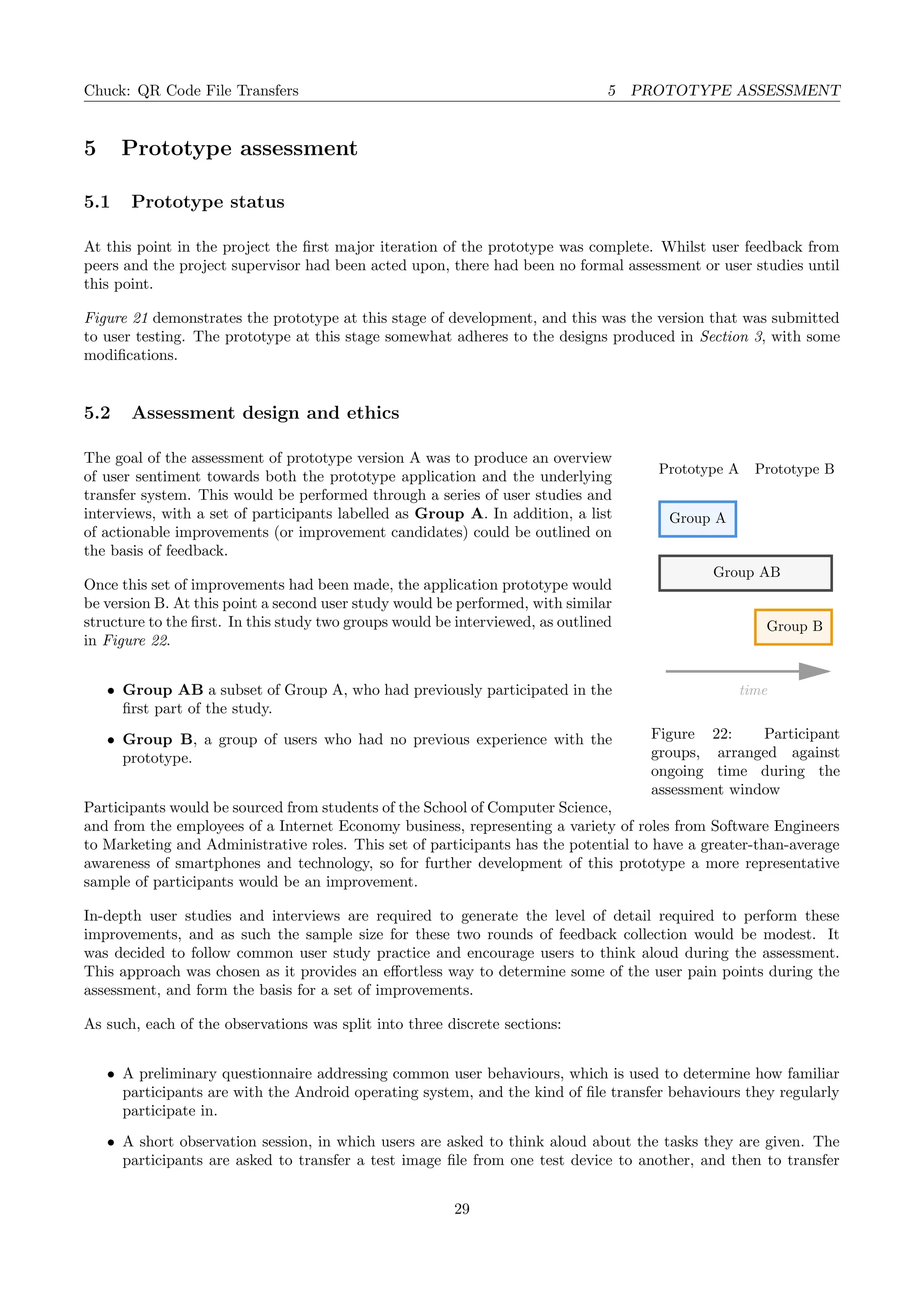

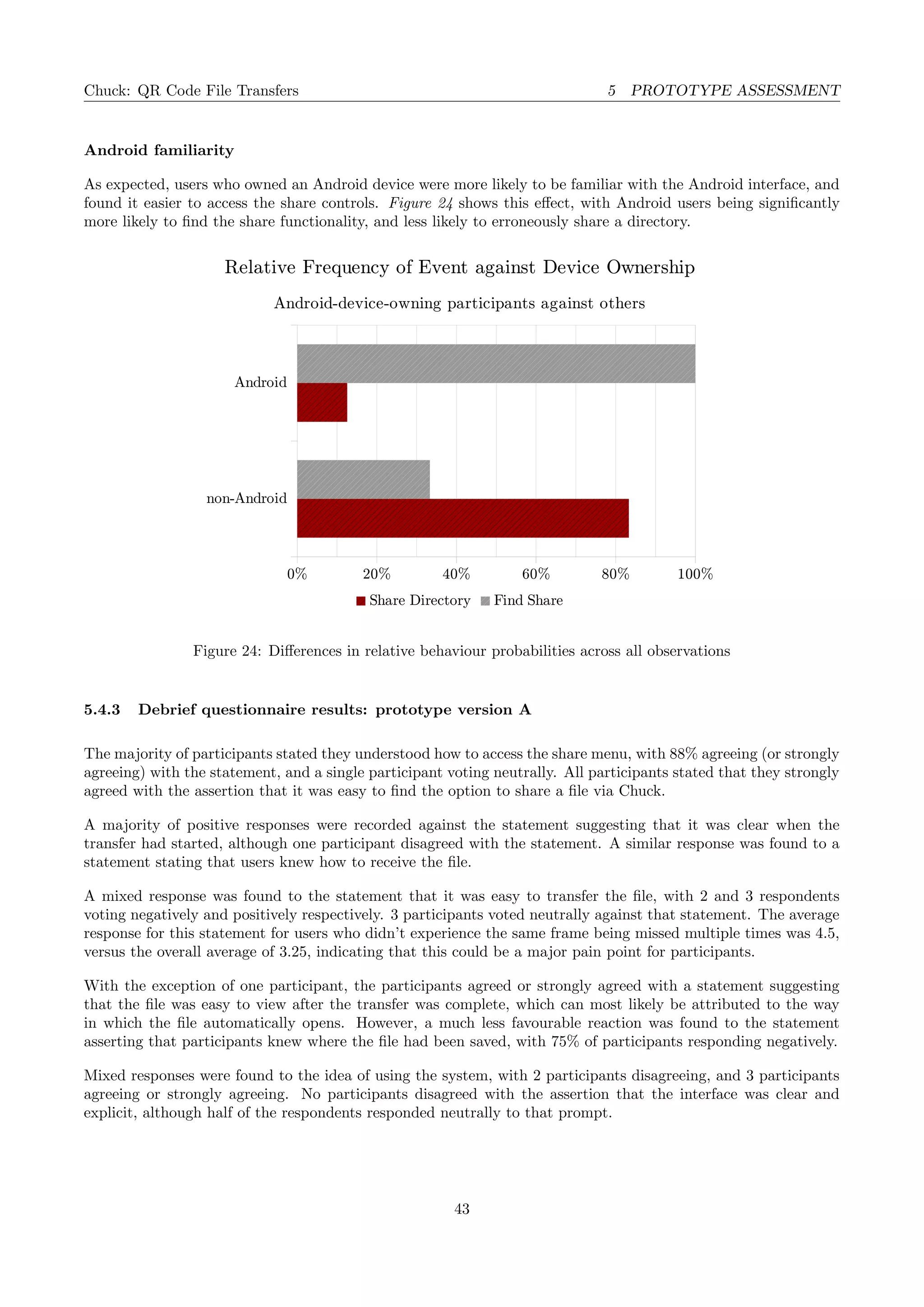

# Question Answers

1 I understood how to access the share menu from the file manager

(5-point Likert scale)

5 - Strongly Agree

1 - Strongly Disagree

2 Finding the option to send the file via Chuck was easy

(5-point Likert scale)

5 - Strongly Agree

1 - Strongly Disagree

3 It was clear when the transfer had started

(5-point Likert scale)

5 - Strongly Agree

1 - Strongly Disagree

4 I knew how to receive the file on the tablet device

(5-point Likert scale)

5 - Strongly Agree

1 - Strongly Disagree

5 It was easy to transfer the file

(5-point Likert scale)

5 - Strongly Agree

1 - Strongly Disagree

6 It was easy to view the file once the transfer was complete

(5-point Likert scale)

5 - Strongly Agree

1 - Strongly Disagree

7 I know where the file has been saved

(5-point Likert scale)

5 - Strongly Agree

1 - Strongly Disagree

8 I’d consider using this as a method to transfer files between devices

(5-point Likert scale)

5 - Strongly Agree

1 - Strongly Disagree

9 The interface was clear and explicit about the transfer process

(5-point Likert scale)

5 - Strongly Agree

1 - Strongly Disagree

Table 2: Questions asked during the debrief questionnaire

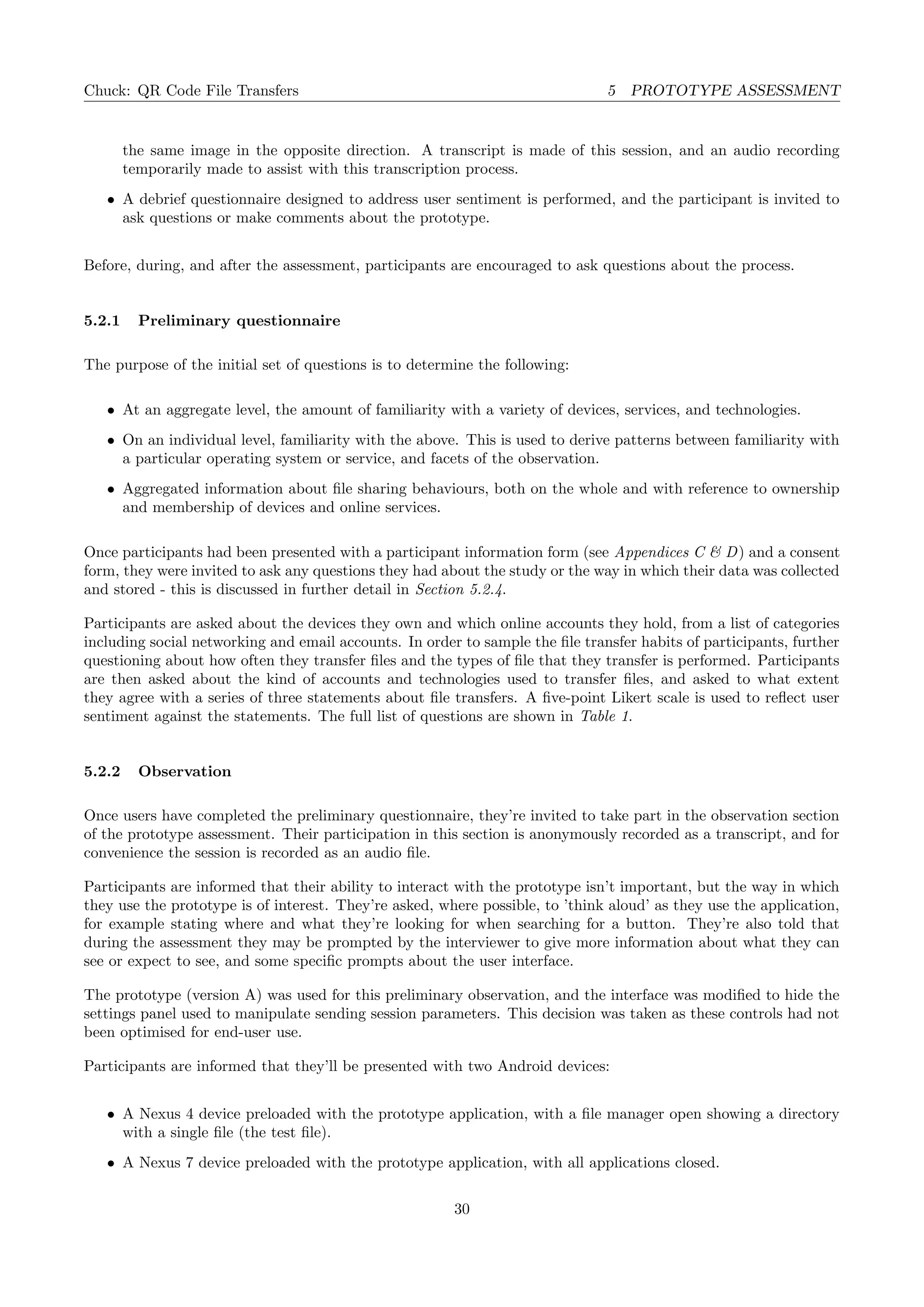

5.2.4 Ethical considerations

According to the University of St Andrews School of Computer Science Ethics Pre-assessment Form [24], full

ethical approval is not required for this assessment, as user contributions are kept anonymous. During the process

of the study, some participants were given temporary tokens to represent their identity between observation

sessions. These tokens took the form of randomly-assigned numbers that they were asked to remember or write

down. Numbers were chosen from the set 1 − 50 for the first wave of observations, and 50 − 100 for the second.

This system meant that even though user observation sessions may have occurred several weeks apart, it was

possible to compare an individual user’s responses between the sessions.

Information about token allocation was never stored, and participant consent forms (see Appendix D) were stored

securely and separately from the participation data. As such, it is not (and was not possible during the study)

to link a participant with their data contribution, preserving anonymity.

Recordings taken as part of the assessment were destroyed as soon as the results of the observations were distilled,

a process discussed in Section 5.3.

33](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/827d5c14-a857-456c-a57a-aad576e3a721-160405153539/75/CS4099Report-33-2048.jpg)

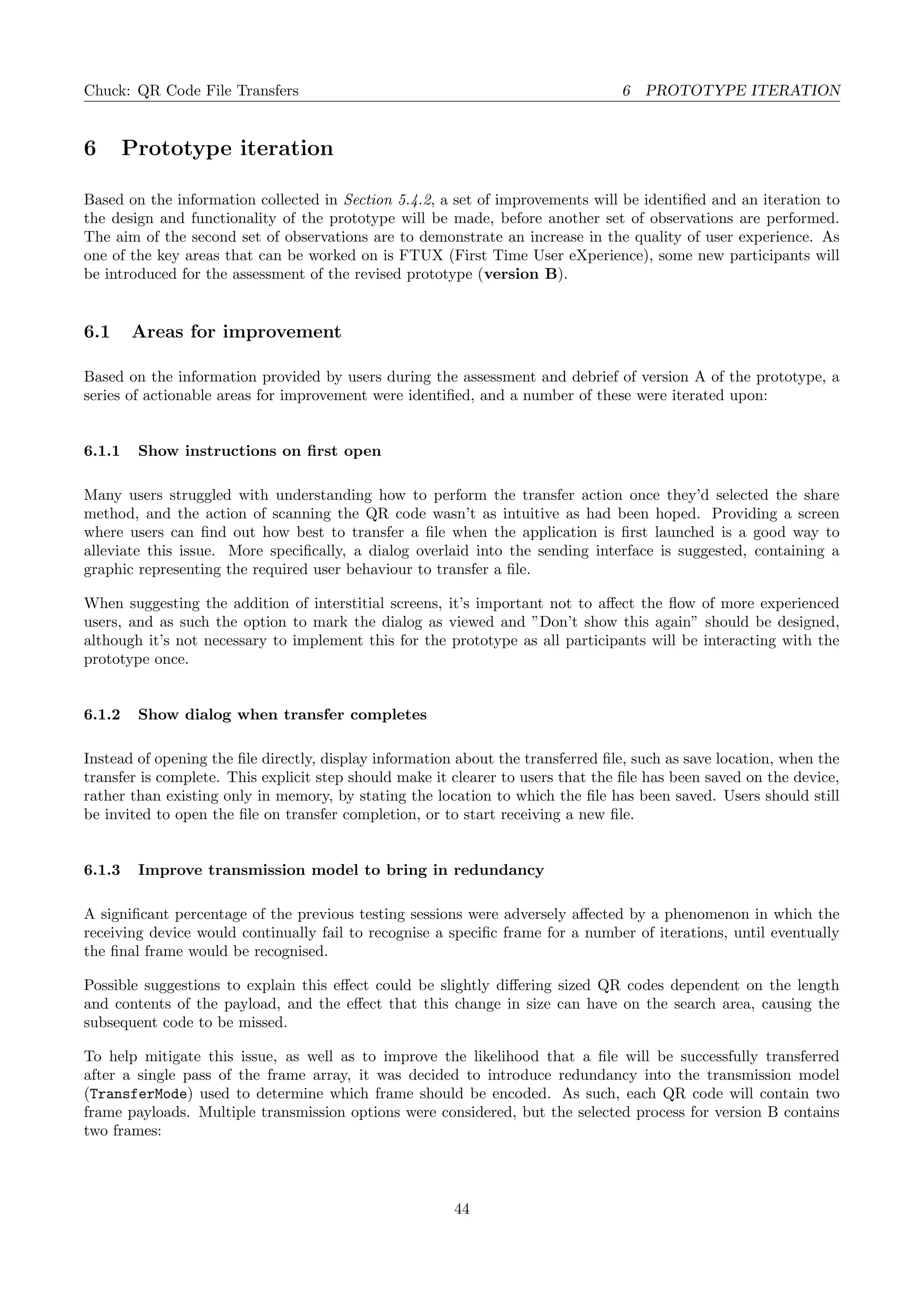

![Chuck: QR Code File Transfers 6 PROTOTYPE ITERATION

• The next frame in an incrementing sequence (ie the same frame as the existing sequential model would

return)

• A randomly selected frame from the frame array

6.1.4 Bring in sending settings as a collapsible panel

Advanced users (as well as the researcher) may wish to alter the transmission settings from within the sending

application, but most users would not want to make use of this functionality. The appearance of form controls

could serve to confuse casual users, which formed the basis of the decision to remove the settings panel during

the earlier testing sequence.

6.2 Process

Commentary about application and code structure in this section pertains to the second

version of the implementation shown to participants - this version is represented by git commit

7bfde4e574024ade65c959d3489b61de41310420 in the submission implementation folder.

This can be accessed via git checkout master or through the APK file ImplementationVersionB.apk. More

information on sideloading APK files can be found in Appendix A

For the rest of this document this build shall be referred to as version B of the prototype.

6.2.1 Changes to the transfer system

The addition of redundancy to the transferred frames required changes to the underlying transfer system, as well

as to the structure of the transfer schema. The transfer schema in version A is discussed in more detail in Section

4.1, and contains space for a single payload. In order to support the additional redundancy, the schema was

modified to contain an array of frame objects, each with their own payload. As shown in Figure 25, this allows

a single QR code to contain any number of frames, which shared fields for file information to reduce duplication

of data.

Frame

payload

payloadStart

payloadLength

frameNumber

Frame

File Info

type

name

fileInfo

totalFrames

number

stringRoot node

payloads[]

payload

payloadStart

payloadLength

frameNumber

Figure 25: The modified transmission schema, showing multiple frame payloads

In addition to this protocol change, modifications were made to the application code as follows:

45](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/827d5c14-a857-456c-a57a-aad576e3a721-160405153539/75/CS4099Report-45-2048.jpg)

![Chuck: QR Code File Transfers REFERENCES

References

[1] Pew Research Center. (2015). Device Ownership Over Time http://www.pewinternet.org/data-trend/

mobile/device-ownership/

[2] David Dearman and Jeffery S. Pierce. (2008). “It’s on my other computer!: computing with multiple

devices.” In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’08).

ACM, New York, NY, USA, 767-776. DOI=http://dx.doi.org/10.1145/1357054.1357177

[3] Dropbox. https://www.dropbox.com/

[4] WeTransfer. https://www.wetransfer.com/

[5] Haartsen, J. C. (2000). “The Bluetooth radio system”. Personal Communications, IEEE, 7(1), 28-36.

[6] OpenText. (2011). State of File Transfer [Online]. Available: http://www.connectis.ca/v/ot/d/smft/

secure-mft-state-of-file-transfer-report-2011-wp.pdf

[7] Drew Houston and Arash Ferdowsi. (28 May 2014). “Thanks for helping us grow” on Dropbox Blog [Online].

Available https://blogs.dropbox.com/dropbox/2014/05/thanks-for-helping-us-grow/

[8] Slack. http://slack.com

[9] Facebook Messenger. http://messenger.com

[10] Kumar, T. (2009). Improving pairing mechanism in Bluetooth security. Int. J. Recent Trends Eng, 2(2).

[11] Android Developer Documentation. Common Intents. Available at: http://developer.android.com/

guide/components/intents-common.html. Accessed 2016.

[12] Denso Wave. QR Codes. [Online] Available at: http://www.qrcode.com/en/. Accessed 2016.

[13] Reed, I. S., & Solomon, G. (1960). Polynomial codes over certain finite fields. Journal of the society for

industrial and applied mathematics, 8(2), 300-304.

[14] Braun C. (2011.) Erster QRpedia QR Code im Museum fr Hamburgische Geschichte, whrend er von Martina

Fritz gescannt wird. Wikimedia Commons. [Online] Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/

File:QR_Code,_Museum_f%C3%BCr_Hamburgische_Geschichte_IMG_1607_original.jpg Accessed 2016.

[15] Wang, H. (2012). QR Motion. Nealwang.net. [Online] Available: http://nealwang.net/projects/

qr-motion.html Accessed 2016.

[16] Wang, H. (2012). QR Motion, A new technology based on QR Code. Youtube. [Video - Online] Available:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NoyvXuJbdOI Accessed 2016.

[17] Wang, H. (2012). QR Motion: Interim Report. Nealwang.net. [Online] Available: http://nealwang.net/

projects/InterimReport%5Bdraft%5D.pdf Accessed 2016.

[18] ZXing Java Library. https://github.com/zxing/zxing

[19] Mixpanel. http://mixpanel.com

[20] Google. (2014). Material Design: Introduction. [Online] Available: https://www.google.com/design/

spec/material-design/introduction.html Accessed 2016.

[21] Network.nt. (2007). CCD Barcode Scanner (Argox ArgoScan AS-8000) during scan. Wikimedia Commons.

[Online] Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:CCD_Barcode_Scanner-2.jpg

Accessed 2016.

[22] Rams, D. (2009). Less and more: The design ethos of Dieter Rams. K. Ueki-Polet, & K. Klemp (Eds.).

Gestalten.

56](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/827d5c14-a857-456c-a57a-aad576e3a721-160405153539/75/CS4099Report-56-2048.jpg)

![Chuck: QR Code File Transfers APPENDICES

[23] Vuse. (2010). User Guide: Advanced Information [Online] Available at https://wiki.vuze.com/w/UG_

Advanced_Information

[24] University of St Andrews School of Computer Science Ethics Guidelines Computer Science Student

Handbook. [Online]. Available: https://info.cs.st-andrews.ac.uk/student-handbook/academic/

ethics.html Accessed 2016.

Appendix A: Sideloading APK Files

This submission is accompanied by two APK files, ready for installation onto compatible Android devices.

Before installation can be attempted, the device must be set up to accept unknown installation sources:

• Open the Settings application from the application drawer

• Choose Security

• Enabled the checkbox next to Unknown sources

Installation method 1: file transfer

Transfer the APK file to the device via Bluetooth, Email or by loading the APK file directly onto the devices

external storage, if present. The APK file can then be executed from within a file manager application, triggering

installation of the prototype.

Installation method 2: download

Upload the APK file to an internet-accessible location, such as a local or public webserver, and download the file

to the device using the browser. As before, the APK file can be executed from within the browser’s download

manager.

Installation method 3: developer mode

Enable the device’s developer settings by opening the settings application and selecting About device. Tapping

the Build number of the device seven times should enable developer options from within settings. From here, the

option to enable USB debugging should be enabled.

Download the Android SDK or a standalone copy of ADB(Android Debug Bridge) onto a PC and connect the

Android device to the PC via USB. The command to install an APK file through ADB is:

adb install <path-to-apk-file>

Conflicting versions

It may be necessary to uninstall previous versions of the prototype before installing a new APK.

57](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/827d5c14-a857-456c-a57a-aad576e3a721-160405153539/75/CS4099Report-57-2048.jpg)