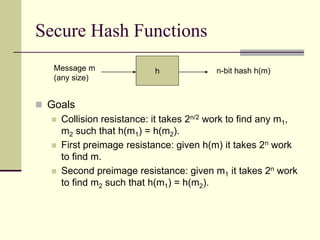

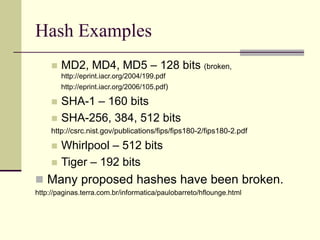

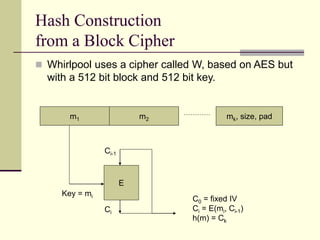

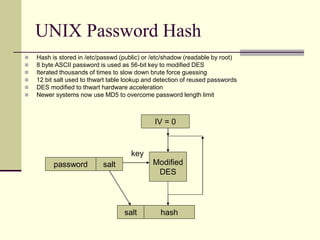

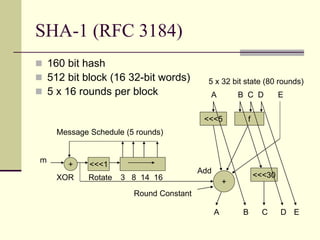

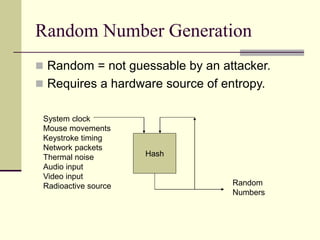

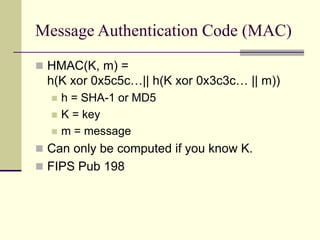

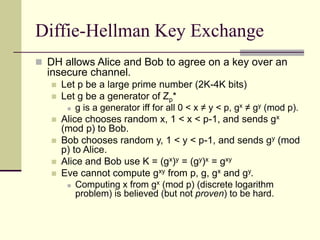

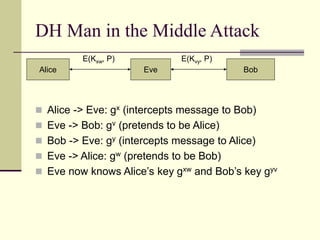

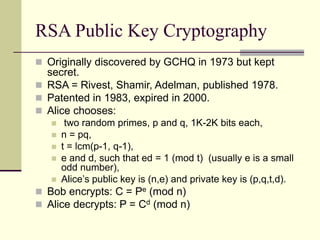

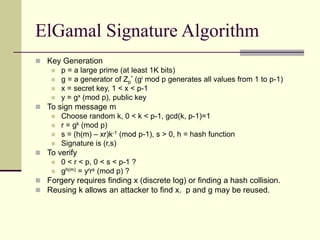

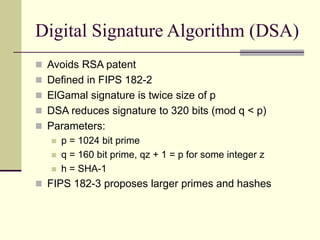

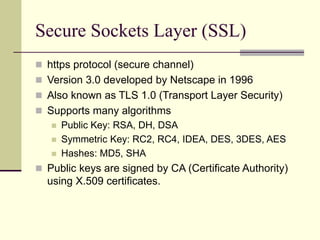

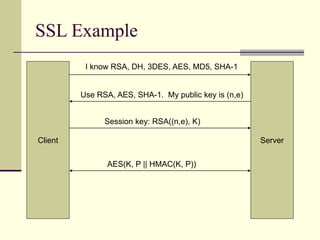

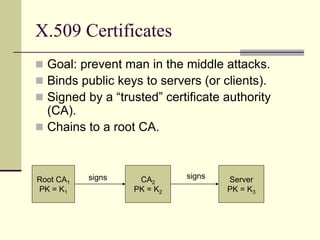

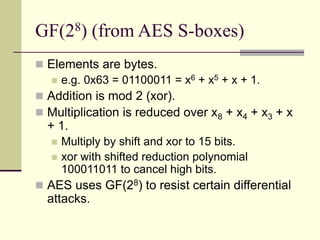

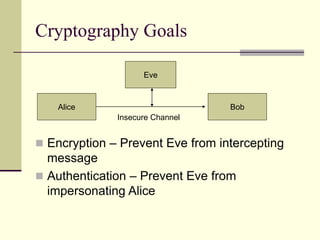

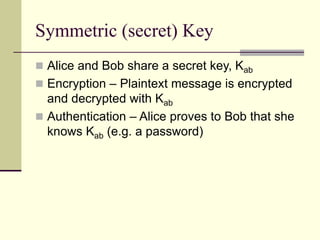

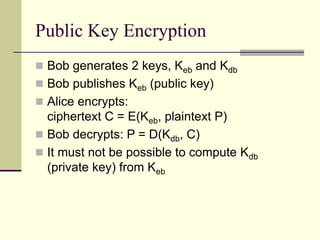

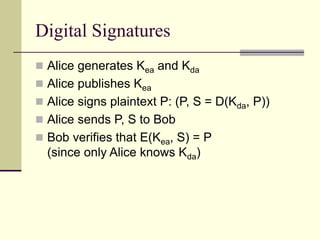

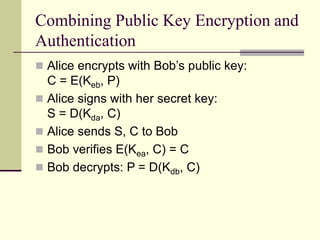

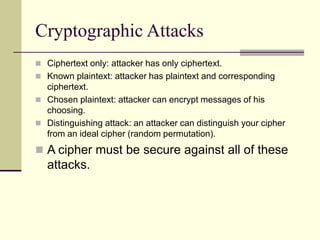

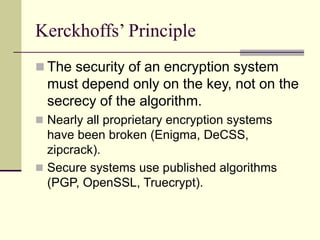

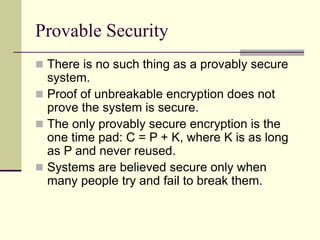

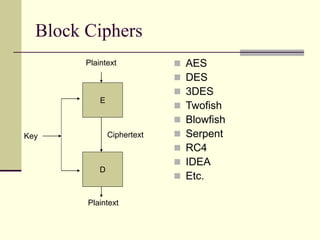

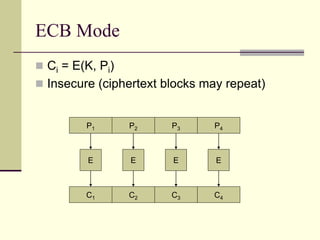

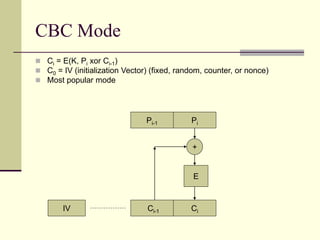

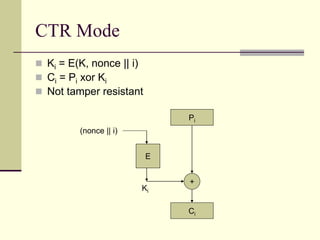

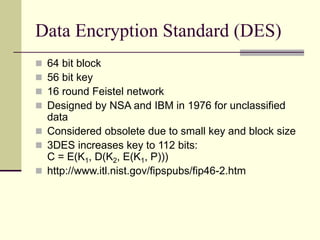

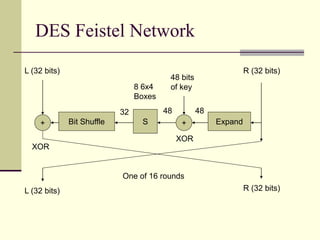

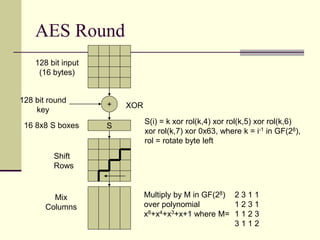

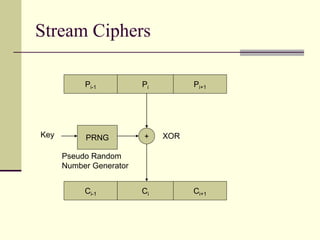

The document provides an introduction to cryptography, including definitions of key terms, goals of cryptography like encryption and authentication, and descriptions of common cryptographic techniques. It summarizes symmetric key encryption where a shared secret key is used for both encryption and decryption, public key encryption using key pairs, digital signatures to authenticate messages, and how public key encryption and signatures can be combined. It also discusses cryptographic attacks, Kerckhoffs' principle of secrecy depending on the key not the algorithm, provable security, block ciphers like AES and DES, encryption modes, stream ciphers, hash functions, message authentication codes, key exchange methods like Diffie-Hellman, and public key cryptosystems like RSA and ElGamal

![RC4 Stream Cipher

Key Schedule

for i from 0 to 255 S[i] := i

j := 0

for i from 0 to 255

j := (j + S[i] + key[i mod keylength]) mod 256

swap(S[i],S[j])

Keystream Generation

i := 0, j := 0

while GeneratingOutput:

i := (i + 1) mod 256

j := (j + S[i]) mod 256

swap(S[i],S[j])

output S[(S[i] + S[j]) mod 256]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/crypto-230205165224-b68e0896/85/crypto-ppt-26-320.jpg)