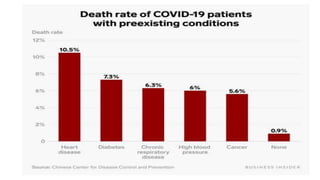

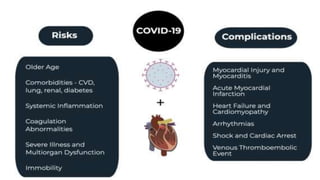

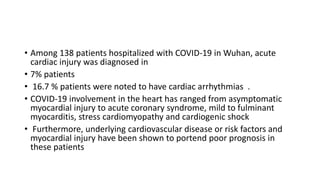

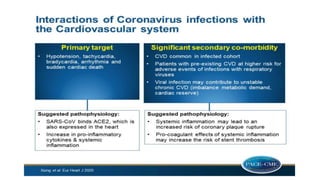

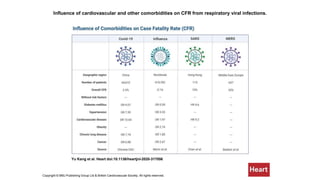

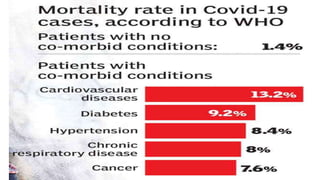

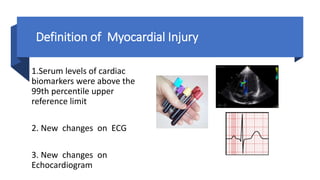

- Patients with cardiovascular disease have a higher mortality rate from COVID-19 according to data from China.

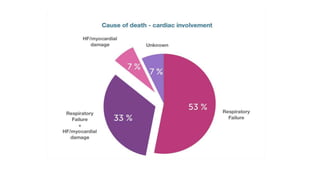

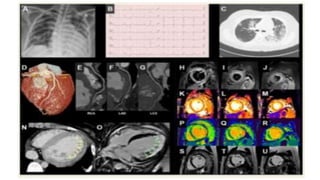

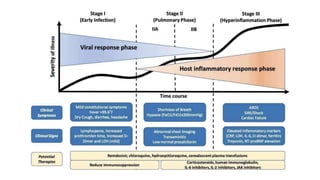

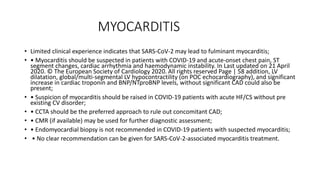

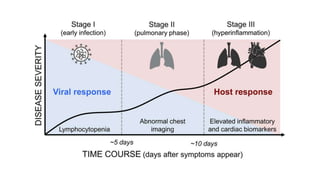

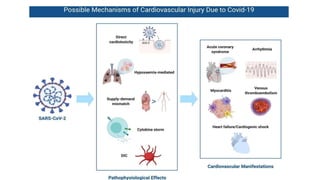

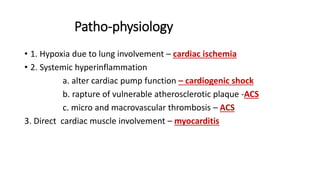

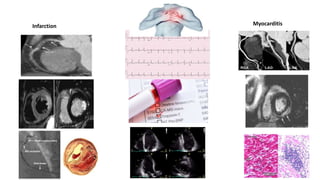

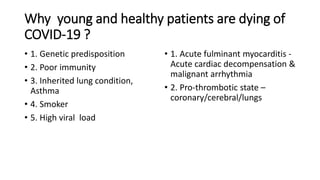

- The pathophysiology of cardiac involvement in COVID-19 can include hypoxia, hyperinflammation leading to cardiac dysfunction, direct viral myocarditis, and increased risk of thrombosis.

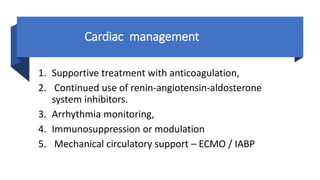

- Treatment is mainly supportive, though renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system inhibitors should generally be continued in stable patients, and immunosuppression or modulation may help in some cases.

![Large-scale epidemiological data from China has identified that patients

with cardiovascular disease have a higher mortality rate from COVID-19

(10.5% vs 0.9% for those without any comorbid conditions, [China CDC,

2020])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covidandheart-221019054943-6772b333/85/COVID-AND-HEART-pptx-6-320.jpg)

![• angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and an ACE inhibitor (ACEI) upregulated

ACE2 expression in animal studies,

• here is no clinical or experimental evidence supporting that ARBs and ACEIs

either augment the susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 or aggravate the severity and

outcomes of COVID-19 at presen

• ACE2 degrades angiotensin II to generate angiotensin 1-7, which activates the

mas oncogene receptor that negatively regulates a variety of angiotensin II

actions mediated by angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AT1R) [26]. Therefore, it is

thought that the ACE2/angiotensin 1-7/mas receptor axis has counteracting

effects against the excessively activated ACE/angiotensin II/AT1R axis, as seen in

hypertension, cardiac hypertrophy, heart failure, and other CVD

• Ang-(1–7) as a vasodilator and anti-trophic peptide in cardiovascular drug therapy](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/covidandheart-221019054943-6772b333/85/COVID-AND-HEART-pptx-28-320.jpg)