This document provides an overview of a workbook titled "Children's Health in All Policies" published by the Kansas Health Institute. The workbook aims to identify policy solutions to improve children's health in Kansas using a "Health in All Policies" approach. It describes a five-step process for implementing this approach which involves identifying a children's health issue, describing its impact in Kansas, identifying policy opportunities, promising policy solutions, and potential impacts. The document then outlines six key children's health issues addressed in the workbook: obesity, oral health, special needs, risks behaviors, child care access, and poverty.

![Children’s Health in All Policies 3

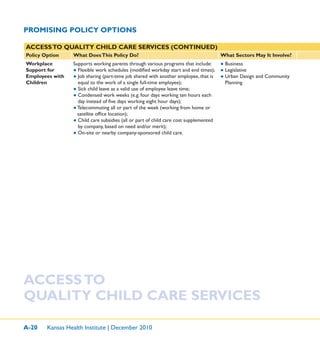

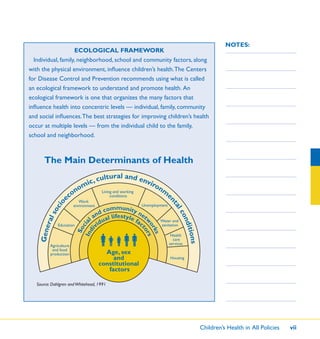

NOTES:measures in other sectors. Kansas policymakers have plentiful opportunities

to improve children’s health and safety at the local and state levels in

multiple sectors such as transportation (e.g., encouraging “active transport”

by providing safe routes for walking and biking to schools) or education

(e.g., mandatory active physical education).

The goal of CHAP is to engage stakeholders, including Kansas legislators

and representatives from government and nongovernment organizations, in

exploring opportunities to create an integrated child health policy response

across multiple sectors.

CHAP is an enormously challenging strategy. Janet Collins, director of

the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion

at the CDC, has defined this strategy as one in “which policies in social

sectors such as transportation, housing, employment and agriculture ideally

would contribute to [children’s] health and health equity.”4

Using the tools and examples in this workbook, you will be able to

identify effective and systematic action for the improvement of our

children’s health. An essential part of informing policymaking is examining

the evidence base for programs and policies. This workbook also includes

an appendix of evidence-informed policy approaches.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0bbd55d4-d782-4cb8-85c7-c3f101aeac7a-161207020912/85/CHAPWorkbook-15-320.jpg)