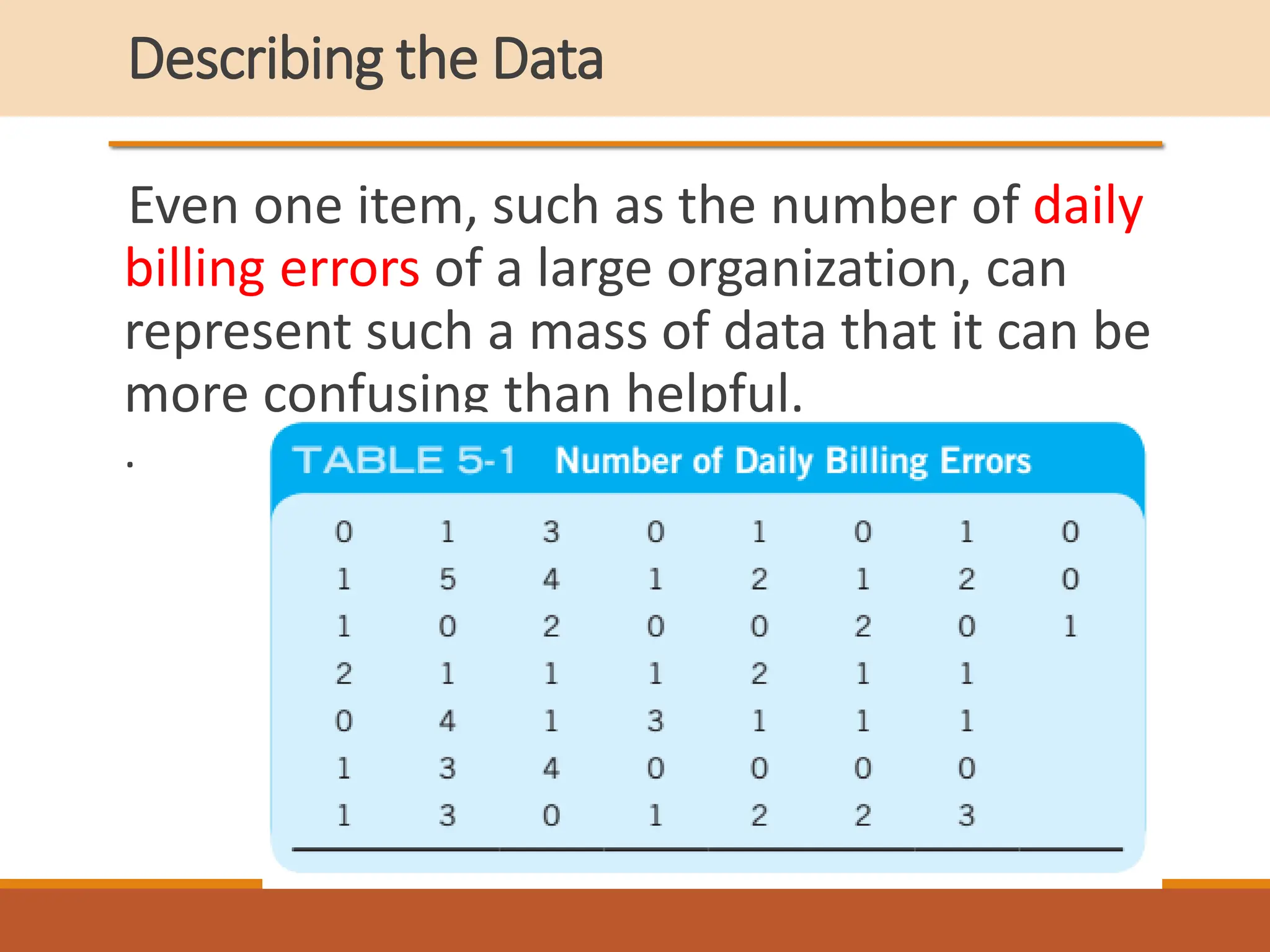

The document provides an overview of statistics and its application in quality control, outlining the definitions, methods of data collection, and analysis. It discusses the distinction between descriptive and inductive statistics, as well as different types of data (variables vs. attributes) and their graphical and analytical representations. Additionally, it covers measures of central tendency, dispersion, and the significance of the normal distribution in understanding data behavior.

![THE NORMAL CURVE

All normal distributions of continuous

variables can be converted to the

standardized normal distribution by using

the standardized normal value, Z.

For example, consider the value of 92 ohm

in Figure 5-14 , which is one standard

deviation above the mean

[µ + 1*σ= 90 + 1(2)= 92].

Conversion to the Z value is

65](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter5fundamentalsofstatisticsl-240606193058-7ddb6b3a/75/Chapter_5-Fundamentals-of-statisticsl-pdf-65-2048.jpg)