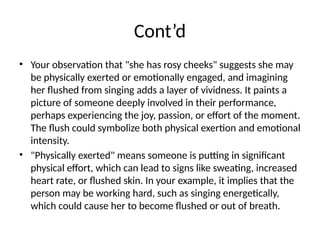

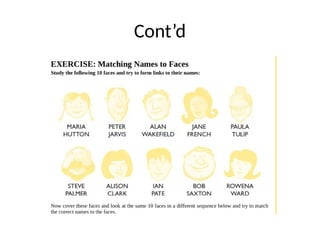

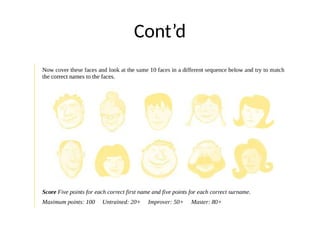

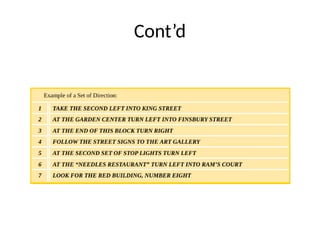

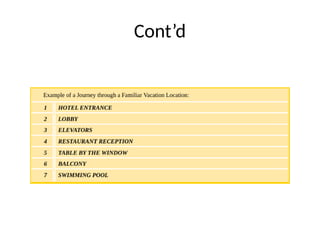

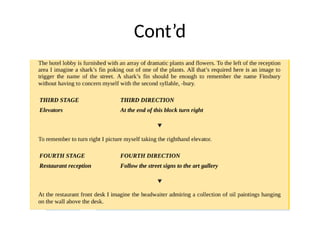

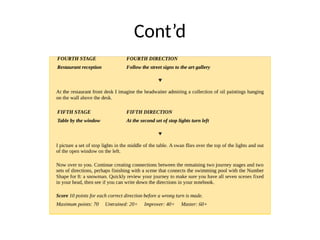

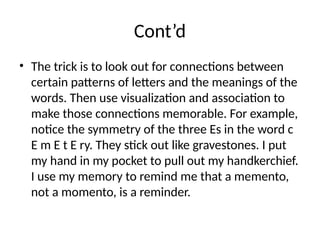

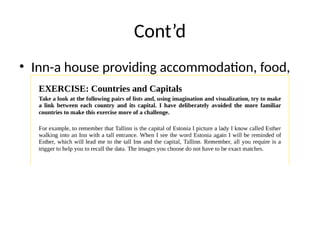

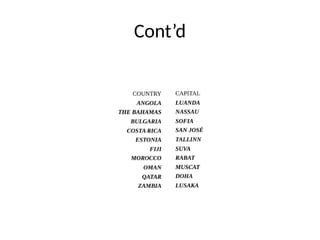

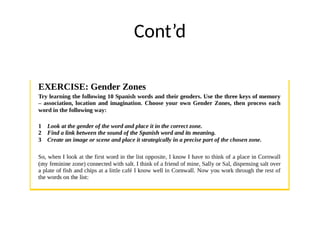

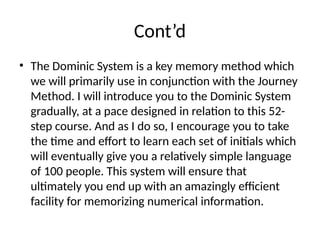

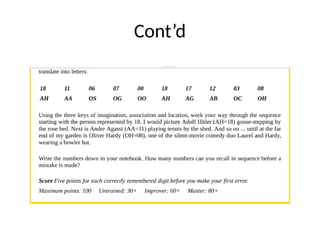

Chapter 2 of the document discusses various techniques for improving memory, focusing on methods to remember names, directions, spellings, countries and capitals, and learning foreign languages. It emphasizes the use of mnemonics, visualization, and creating associations to enhance recall, as well as the significance of personal location and imagery in committing information to memory. Additionally, it explores the idea of 'time travel' as a way to retrieve significant past memories by revisiting places tied to those experiences.