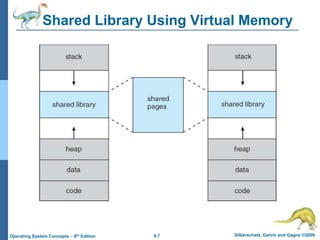

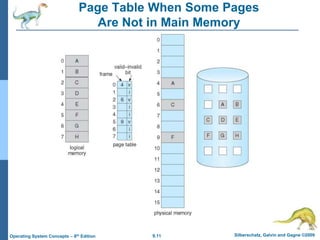

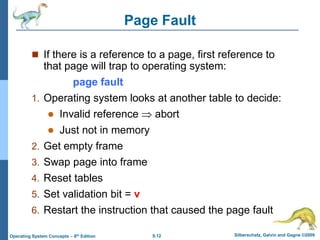

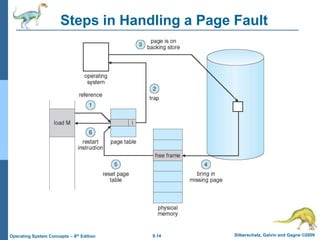

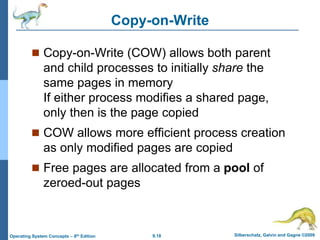

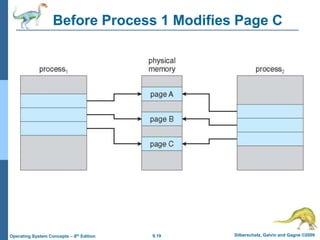

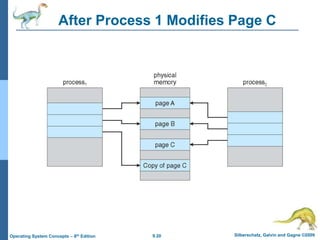

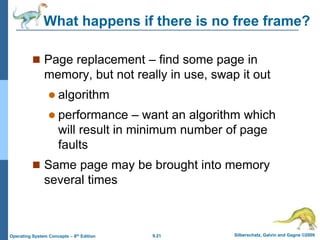

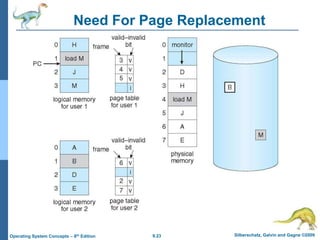

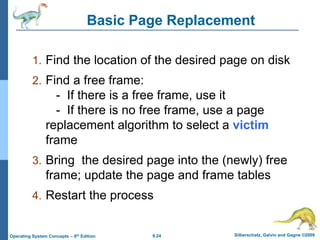

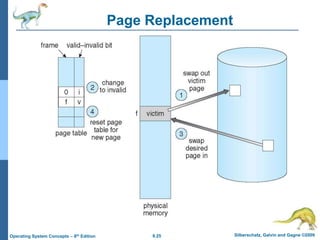

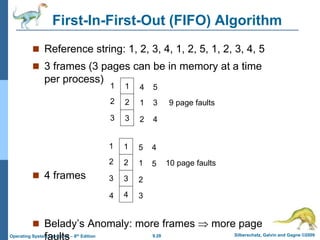

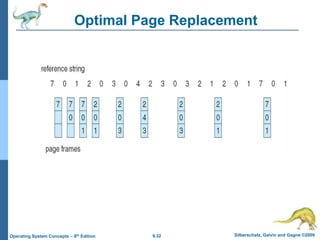

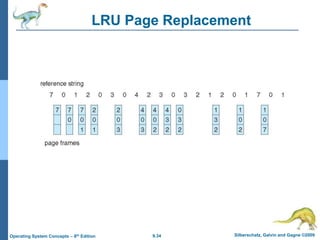

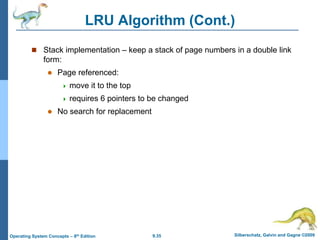

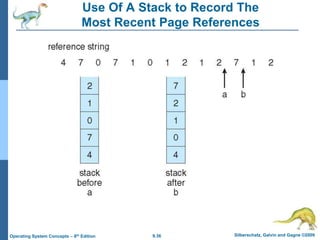

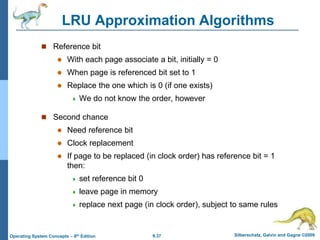

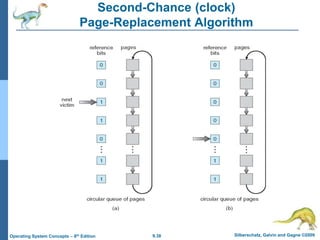

This document summarizes key concepts from Chapter 9 of the textbook "Operating System Concepts - 8th Edition" on virtual memory. It discusses demand paging, where pages are brought into memory only when needed; copy-on-write, which allows processes to initially share pages; page replacement algorithms like FIFO and LRU that select pages to swap out when new pages are needed; and the risks of thrashing when processes do not have enough allocated memory. The document provides examples and diagrams to illustrate these virtual memory techniques.

![9.64 Silberschatz, Galvin and Gagne ©2009

Operating System Concepts – 8th Edition

Other Issues – Program Structure

Program structure

Int[128,128] data;

Each row is stored in one page

Program 1

for (j = 0; j <128; j++)

for (i = 0; i < 128; i++)

data[i,j] = 0;

128 x 128 = 16,384 page faults

Program 2

for (i = 0; i < 128; i++)

for (j = 0; j < 128; j++)

data[i,j] = 0;

128 page faults](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/ch9-230131060850-42b1db6c/85/ch9-ppt-64-320.jpg)