Ccie And Ccde Written Exam Evolving Technologies Version 11 Study Guide Nicholas J Russo

Ccie And Ccde Written Exam Evolving Technologies Version 11 Study Guide Nicholas J Russo

Ccie And Ccde Written Exam Evolving Technologies Version 11 Study Guide Nicholas J Russo

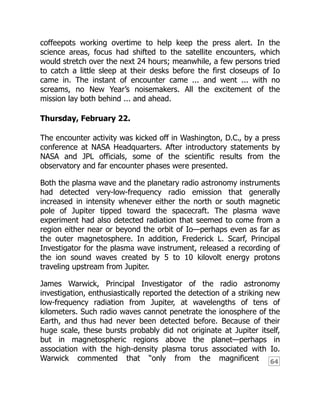

![As Voyager 1 approached Jupiter, the resolution of the images steadily

improved. In October 1978, at a distance of about 125 million kilometers,

the image was less clear than would be obtained with an Earth-based

telescope. [P-20790]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/26819583-250512185031-6cb3f2ed/85/Ccie-And-Ccde-Written-Exam-Evolving-Technologies-Version-11-Study-Guide-Nicholas-J-Russo-29-320.jpg)

![By December 10, the spacecraft had moved to a distance of 85 million

kilometers, and the resolution was about 2000 kilometers, comparable to

the best telescopic images. [P-20829C]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/26819583-250512185031-6cb3f2ed/85/Ccie-And-Ccde-Written-Exam-Evolving-Technologies-Version-11-Study-Guide-Nicholas-J-Russo-30-320.jpg)

![On January 9, 1979 (c), at a distance of 54 million kilometers, the image

surpassed all ground-based views and approached the resolution of the

Pioneer 10 and 11 photos. [P-20926C]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/26819583-250512185031-6cb3f2ed/85/Ccie-And-Ccde-Written-Exam-Evolving-Technologies-Version-11-Study-Guide-Nicholas-J-Russo-31-320.jpg)

![58

In this, taken January 24 at a distance of 40 million kilometers, the

resolution exceeded 1000 kilometers. [P-20945C]

The Observatory Phase](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/26819583-250512185031-6cb3f2ed/85/Ccie-And-Ccde-Written-Exam-Evolving-Technologies-Version-11-Study-Guide-Nicholas-J-Russo-32-320.jpg)

![59

The Galilean satellites of Jupiter first began to show as tiny worlds, not

mere points of light, as the Voyager 1 observatory phase began. In this

view taken January 17, 1979, at a range of 47 million kilometers, the

differing sizes and surface reflectivities (albedos) of Ganymede (right

center) and Europa (top right) are clearly visible. The view of Jupiter is

unusual in that the Great Red Spot is not easily visible, but can just be

seen at the right edge of the planet. Most pictures selected for

publication include the photogenic Red Spot. [P-20938C]

Far Encounter Phase

By early February Jupiter loomed too large in the narrow-angle

camera to be photographed in one piece; 2 × 2 three-color (violet,

orange, green) sets of pictures were taken for the next two weeks;

by February 21, Jupiter had grown too large even for that, and 3 × 3

sets were scheduled to begin. When these sets of pictures are pasted

together to form a single picture, the result is called a mosaic.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/26819583-250512185031-6cb3f2ed/85/Ccie-And-Ccde-Written-Exam-Evolving-Technologies-Version-11-Study-Guide-Nicholas-J-Russo-34-320.jpg)

![By February 1, 1979, Voyager 1 was only 30 million kilometers from

Jupiter, and the resolution of the imaging system corresponded to about

600 kilometers at the cloud tops of the giant planet. At this time, a great

deal of unexpected complexity became apparent around the Red Spot,

and movie sequences clearly showed the cloud motions, including the

apparent six-day rotation of the Red Spot. [P-20993C]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/26819583-250512185031-6cb3f2ed/85/Ccie-And-Ccde-Written-Exam-Evolving-Technologies-Version-11-Study-Guide-Nicholas-J-Russo-35-320.jpg)

![60

One of the most spectacular planetary photographs ever taken was

obtained on February 13 as Voyager 1 continued its approach to Jupiter.

By this time, at a range of 20 million kilometers, Jupiter loomed too large

to fit within a single narrow-angle imaging frame. Passing in front of the

planet are the inner two Galilean satellites. Io, on the left, already shows

brightly colored patterns on its surface, while Europa, on the right, is a

bland ice-covered world. The scale of all of these objects is huge by

terrestrial standards; Io and Europa are each the size of our Moon, and

the Red Spot is larger than the Earth. [P-21082C]

While the imaging experiments were in the limelight, the other

scientific instruments had also begun to concentrate on the Jovian

system. The ultraviolet spectrometer had been scanning the region

eight times a day; the infrared spectrometer (IRIS) spent 1½ hours a

day analyzing infrared emissions from various longitudes in Jupiter’s

atmosphere; the planetary radio astronomy and plasma wave](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/26819583-250512185031-6cb3f2ed/85/Ccie-And-Ccde-Written-Exam-Evolving-Technologies-Version-11-Study-Guide-Nicholas-J-Russo-36-320.jpg)

![The Voyager Project was operated from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory

managed for NASA by the California Institute of Technology. Located in

the hills above Pasadena, California, JPL is the main center for U.S.

exploration of the solar system. [JB17249BC]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/26819583-250512185031-6cb3f2ed/85/Ccie-And-Ccde-Written-Exam-Evolving-Technologies-Version-11-Study-Guide-Nicholas-J-Russo-38-320.jpg)

![62

The colors used to print the three separate frames can be seen clearly in

the nonoverlapping areas. For other pictures in this book, the

nonoverlapping partial frames are omitted. [P-21192]

The pictures from Voyager are “clearly spectacular,” said Lonne Lane,

Assistant Project Scientist for Jupiter. “We’re getting even better

results than we had anticipated. We have seen new phenomena in

both optical and radio emissions. We have definitely seen things that

are different—in at least in one case, unanticipated—and are begging

for answers we haven’t got.” There was already, still almost a month

from encounter, a strong feeling of accomplishment among the

scientists and engineers; they had done a difficult task and it has

been successful.

By the last week of February 1979, the attention of thousands of

individuals was focused on the activities at JPL. Scientists had arrived

from universities and laboratories around the country and from

abroad, many bringing graduate students or faculty colleagues to

assist them. Engineers and technicians from JPL contractors joined

NASA officials as the Pasadena motels filled up. Special badges were

issued and reserved parking areas set aside for the Voyager influx.

Twenty-four hours a day, lights burned in the flight control rooms, the

science offices, the computer areas, and the photo processing labs.

In order to protect those with critical tasks to perform from the

friendly distraction of the new arrivals, special computer-controlled

locks were placed on doors, and security officers began to patrol the

halls. By the end of the month the press had begun to arrive. Amid

accelerating excitement, the Voyager 1 encounter was about to

begin.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/26819583-250512185031-6cb3f2ed/85/Ccie-And-Ccde-Written-Exam-Evolving-Technologies-Version-11-Study-Guide-Nicholas-J-Russo-40-320.jpg)

![63

where one can see to greater depths in the atmosphere. This photo was

taken March 1 from a distance of 4 million kilometers. [P-21183C]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/26819583-250512185031-6cb3f2ed/85/Ccie-And-Ccde-Written-Exam-Evolving-Technologies-Version-11-Study-Guide-Nicholas-J-Russo-42-320.jpg)

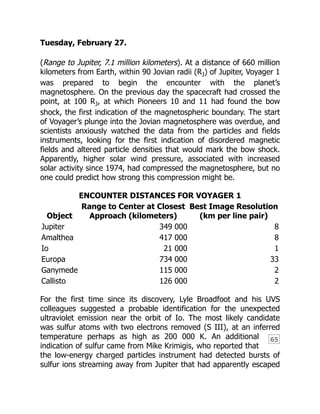

![Not until March 2, at a distance of less than 45 RJ, would the

spacecraft enter the magnetosphere for the final time.

At 11 a.m. the first daily briefing to the press was given. “After nearly

two months of atmospheric imaging and perhaps a week or two of

satellite viewing, [we’re] happily bewildered,” said Brad Smith. The

Jovian atmosphere is “where our greatest state of confusion seems to

exist right at the moment, although over the next several days we

may find that some of our smirking geology friends will find

themselves in a similar state. I think, for the most part, we have to

say that the existing atmospheric circulation models have all been

shot to hell by Voyager. Although these models can still explain some

of the coarse zonal flow patterns, they fail entirely in explaining the

detailed behavior that Voyager is now revealing.” It was thought,

from Pioneer results, that Jupiter’s atmosphere showed primarily

horizontal or zonal flow near the equatorial region, but that the zonal

flow pattern broke down at high latitudes. But Voyager found that

“zonal flow exists poleward as far as we can see.”

Smith also showed a time-lapse movie of Jupiter assembled from

images obtained during the month of January. Once each rotation,

approximately every ten hours, a color picture had been taken.

Viewed consecutively, these frames displayed the complex cloud

motions on a single hemisphere of Jupiter, as they would be seen

from a fixed point above the equator of the planet. The film revealed

that clouds move around the Great Red Spot in a period of about six

days, at speeds of perhaps 100 meters per second. The Great Red

Spot, as well as many of the smaller spots that dot the planet,

appeared to be rotating anticyclonically. Anticyclonic motion is

characteristic of high-pressure regions, unlike terrestrial storms.

Smith noted that “Jupiter is far more complex in its atmospheric

motions than we had ever imagined. We are seeing a much more

complicated flow of cyclonic and anticyclonic vorticity, circulation. We

see currents which flow along and seem to interact with an obstacle

and turn around and flow back.” There is a Jovian jet stream that is

“moving along at well over 100 meters per second. Several of these](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/26819583-250512185031-6cb3f2ed/85/Ccie-And-Ccde-Written-Exam-Evolving-Technologies-Version-11-Study-Guide-Nicholas-J-Russo-49-320.jpg)