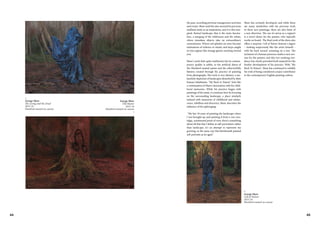

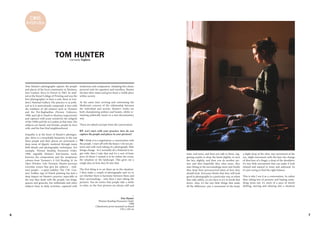

Tom Hunter captures intimate portraits of friends and community members in Hackney, London, drawing inspiration from Dutch masters like Vermeer in his compositions. While his photographs depict ordinary people facing housing issues, commercial galleries have represented his work, which Hunter sees as allowing his critical messages to reach broader audiences. He finds the balance between staged and documentary photography most interesting to explore people's relationships with their surroundings.

![12 13

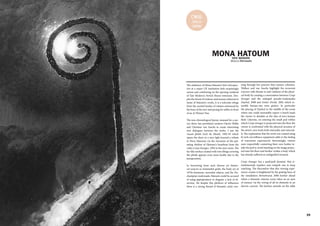

Vija Celmins

Ocean

1975

Litograph on Paper

31 x 47 cm

>

captivating as a lava field or an intricate pattern

of pools that make up Iceland's wilderness."6

The

depicted landscape is transformed through the

artist's sense of the place to become a new land-

scape made of graphite and paper rather than

water, rocks, trees or lava.

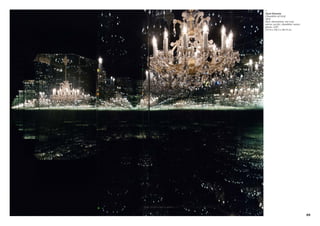

Horn's sculpture Untitled ("Consider incomplete-

ness as a verb") both reflects and alters its immedi-

ate landscape.7

The work is composed of two glass

cubes of slightly different shades of blue; their

sides are a rough, milky opaqueness, the top is a

smooth, shiny translucence. As the outside light

changes with the weather, so do the cubes as they

hermetically absorb the natural light, transforming

it into graspable yet surreal colours, from cerulean

to amethyst, which are present but rare in the nat-

ural world.8

Although, from afar, the cube's solid-

ness and stillness seem to contain and stabilize the

light, the surface of the cube shifts when the view-

er approaches, as though the light changed within

the cube itself, in a corporeal response to the new

presence. The cubes bring attention to mundane

elements of our immediate landscape that are

constantly shifting while simultaneously making

these familiar elements unfamiliar, through hallu-

cinatory colours and anthropomorphic reactions.

As Fer writes, Horn's practice can be described as

creating in the viewer the sensation of a tenuous

grip on our world, as it magnifies, monumentaliz-

es and mystifies the common.9

The transparency of the cubes paradoxically leads

them to visibly fill with elements that are invisi-

ble outside the artwork. Robert Smithson, in a

>

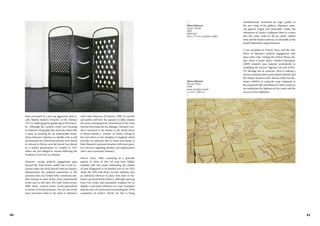

Roni Horn

Bluff Life

1982

Watercolour on graphite

sacred as something or someone to which we

do not have access, but that comes and calls to

us: a tomb, a desirable body, a birdsong.

1. Jean-Luc Nancy. "Techniques du Present ". Le Portique. 15 march 2005. Web

accessed March 24, 2016. http://leportique.revues.org/309

2. Ibid.

3. Jean Luc Nancy, The Muses (Stanford : Stanford University Press, 1996), 76

4. Barker writes of Francis Bacon's figures as embodying Nancy's notion of art

as monstrance. In Bacon, the figure is also an anti-figure. Its monstrous scream

emanates from a non-body, out of the grounding medium, somewhere between

presence and absence. Bacon's figuration visualizes the dynamic slippage of

sense as animal, human, and spirit. Barker, "De-Monstration and the Sense of

Art", in Jean-Luc Nancy and Plural Thinking, ed. Peter Gratton and Marie-Eve

Morin (Albany: SUNY Press, 2012), 184.

5. Briony Fer, Roni Horn aka Roni Horn (New York: Steidl, Tate Modern and

the Whitney Museum of American Art, 2009), 27.

6. Ibid.

7. Mimi Thompson, "Roni Horn", Bomb Magazine 28 (1998), 22.

8. Horn also explores this idea of changing elements in Still Water (The River

Thames), fifteen large photo-lithographs focused on a small surface area of the

river Thames. Their colour and texture varies dramatically as the surface of the

Thames changed with tidal movement and light. Small footnotes included in

the image link to quotations on the significance of the river and the moods and

narratives it evokes.

9. Fer cites Lévi-Strauss to emphasize how our senses can only grasps certain

elements of the world rather than the whole: "I can pick out certain scenes and

separate them from the rest; is it this tree, this flower? They may well be else-

where. Is it also a delusion that the whole should fill me with rapture, while

each part of it, taken separately, escapes me?" Claude Lévi-Strauss quoted by

Fer, Roni Horn aka Roni Horn, 28.

10. Rosalind Krauss quoted by Amy Powell, Depositions : Scenes from the Late

Medieval Church to the Modern Museum (New York: Zone Books, 2012), 249.

disagreement with Judd's belief that his use of

Plexiglass made his sculptures "less mysterious,

less ambiguous", writes: "what is outside [the box-

es] vanishes to meet the inside, while what is in-

side vanishes to meet the outside. The concept of

"anti-matter" overruns, and fills everything, mak-

ing these very definite works verge on the notion

of disappearance."10

The emptiness of the cube's

centre becomes the locus of a melting of both out-

side and inside, leading to a transfiguration of the

natural, mundane exterior, and the man-made, ar-

tistic interior, creating an uncanny materiality. As

Amy Powell writes of Hesse's Repetition Nineteen

III (fig. 8), the cubes and tubes hold their light and

shadow, and the viewer experiences a phenom-

enological vibration as the object continuously

shifts between fullness and emptiness, visibility

and invisibility.

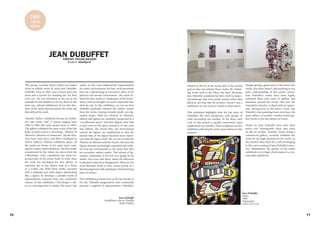

Nancy's ambiguous claim that "art is sensible visi-

bility of this intelligible, that is, invisible, visibility"

can be interpreted through the work of Celmins,

Horn, Hesse and Judd as making sensuously vis-

ible the elements of our world that are intelligible

but normally invisible, either physically or mun-

danely, such as light, shadow, weather, emptiness,

charcoal and paper. There is an element of meta-

morphosis or alchemical transformation as an

element or material becomes other through the

process of art. Through this transformation, view-

ers become closer to these previously invisible el-

ements as the artwork creates a force that enables

them to reach out to us. This reaching out of the

artwork can be related to Nancy's definition of the

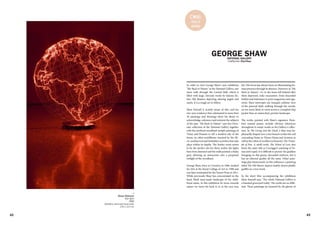

Donald Judd

Untitled

1965

Red flourescent Plexiglass and stainless steel

51 x 122 x 86 cm

>](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/bf03cc6c-2c08-4bf0-a59b-9722c2ab1db0-161212193107/85/C16-2016-7-320.jpg)