The document outlines instructions for a discussion assignment in a course where students must select a key term from their readings. They are required to research at least five scholarly articles on the topic and write a thread consisting of various sections, including an explanation of the key term and a major article summary. Additionally, students must engage in substantive interactions with their peers by commenting on at least three classmates' threads.

![team to accomplish them.

• Talk together about ways to

evaluate whether goals have

been met.

• Construct a family genogram

and ecomap together that will

reveal the illnesses across the

generations.

• Identify resources that can be

drawn upon for support and

information.

• Ask the questions: “ What is one

characteristic that you most

appreciate about [your father]

[your son] [your grandfather]? ” and

follow up with “ Who do you count

on most for support these days? ”

• Remain curious about the answers.

Focus the conversation to build on

the family’s strengths and ability to

problem solve together.

Create a collaborative

relationship and remove

obstacles to change.

2910_Ch07_165-194 06/01/15 11:44 AM Page 180

Denham, Sharon, et al. Family Focused Nursing Care, F. A.

Davis Company, 2015. ProQuest Ebook Central,](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/busi604discussionassignmentinstructionsinstructionsthest-220922010340-40653e53/75/BUSI-604Discussion-Assignment-InstructionsInstructionsThe-st-95-2048.jpg)

![or verbal behavior that

suggests there has been

coercion to participate or

signs of disinterest or

resentment.

• We cannot proceed as if this is

a helping session because we

need to talk about [ the

situation] .

• What should we do about

this?

• Then proceed to co-construct

a solution with which all can

move forward.

• I would be interested in

knowing what is troubling you

today.

• Listen and try to understand

the situation.

• Acknowledge and clarify any

misconceptions.

Ask these questions if not

already used:

• What is the worst advice that

you have been offered by a

provider about healthy

eating?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/busi604discussionassignmentinstructionsinstructionsthest-220922010340-40653e53/75/BUSI-604Discussion-Assignment-InstructionsInstructionsThe-st-117-2048.jpg)

![a

n

y.

A

ll

ri

g

h

ts

r

e

se

rv

e

d

.

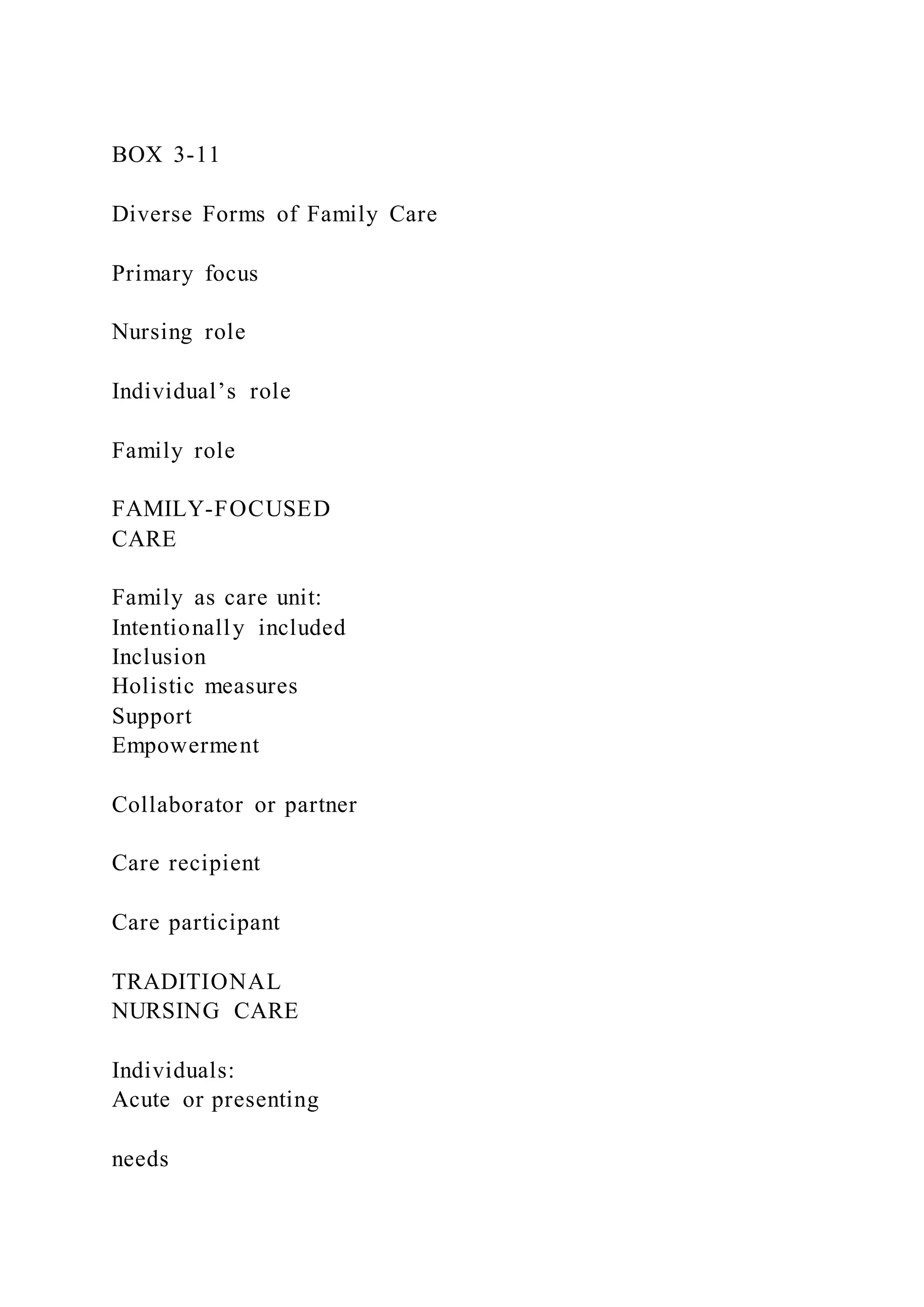

overweight or obese (Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention [CDC], 2011). Obesity

is a growing problem for other countries as well. Growing

numbers of young children are

at risk for becoming obese and even morbidly obese. Obesity is

linked with heart disease,

stroke, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and some forms of cancer.

Medical costs linked with

obesity are in the billions, with obese persons spending $1,429

more annually for health

care than those of normal weight (Finkelstein, Trogdon, Cohen,

& Dietz, 2009). Others

have found that obesity raises medical costs even higher](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/busi604discussionassignmentinstructionsinstructionsthest-220922010340-40653e53/75/BUSI-604Discussion-Assignment-InstructionsInstructionsThe-st-175-2048.jpg)

![About the author

Yasmin Khalili, BSc, MSc, CNN(c) is the Clinical Nurse

Specialist of the Brain Tumour Program at Montreal

Neurological Hospital/McGill University Health Centre. For

further information or to comment on the paper, please contact

Yasmin Khalili by e-mail: [email protected]

Acknowledgements

This paper is dedicated to the memory of J.G. and his wife

and their journey of hope. I learned a lot from you two and

am continuously inspired by your story. I thank you for that.

Special thanks to Toni Vitale, Maria Hamakiotis and Dr.

Judith Ritchie for their help and support. Also, thanks to Pam

Del Maestro for her encouragement to do this paper.

http://jfn.sagepub.com/

Journal of Family Nursing](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/busi604discussionassignmentinstructionsinstructionsthest-220922010340-40653e53/75/BUSI-604Discussion-Assignment-InstructionsInstructionsThe-st-324-2048.jpg)

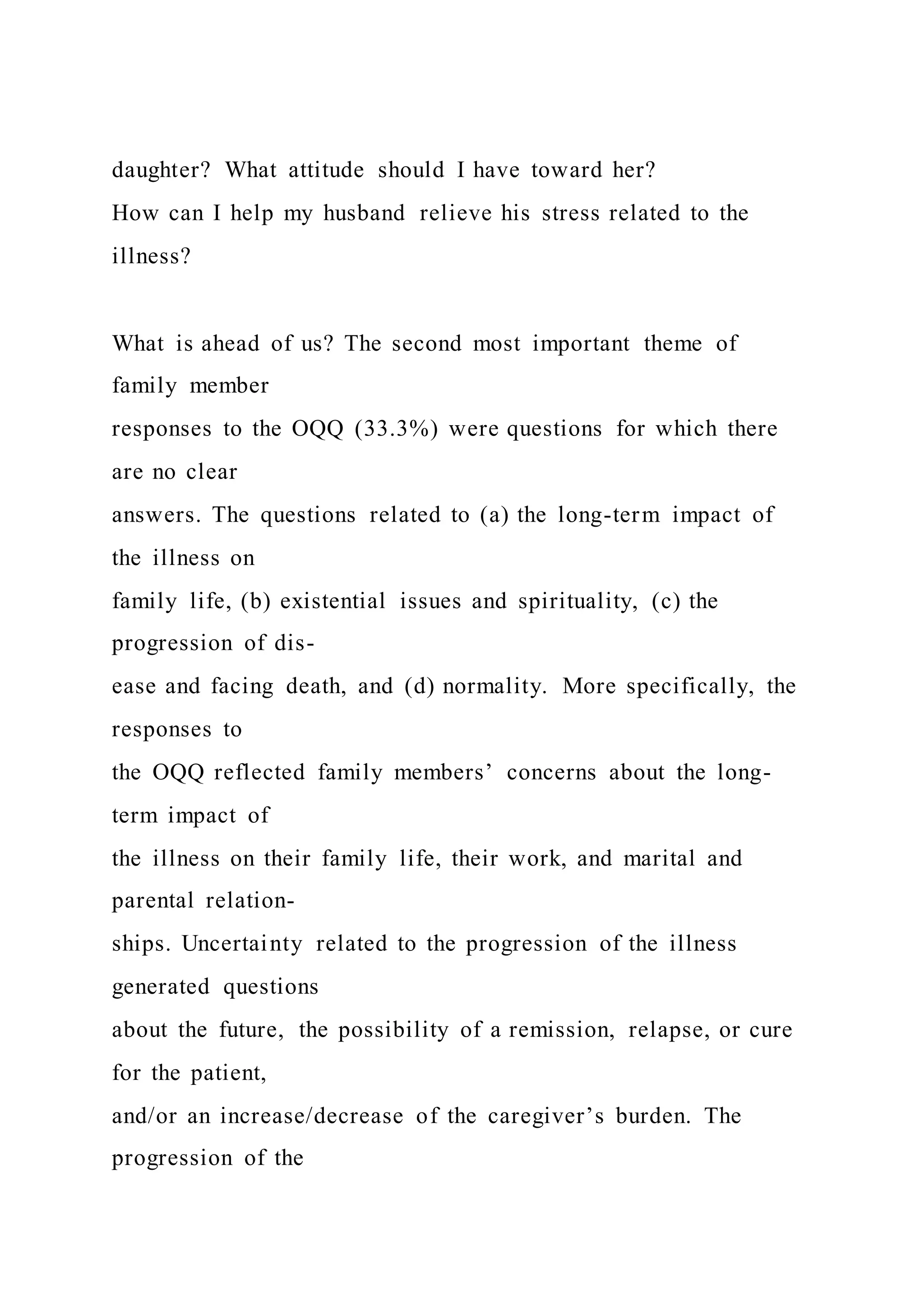

![of a therapeutic conversation; families focused on their need to

deal with the

impact of the illness on the family. The second project

examined responses

of 297 nurses who were asked the question prior to a 1-week

Family

Systems Nursing training program; nurses wanted to know how

to deal with

conflictual relationships between families and health care

professionals and

how to offer families time-efficient interventions. The

responses from both

1University of Montreal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

2University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada

Corresponding Author:

Fabie Duhamel, Faculty of Nursing, University of Montreal,

C.P. 6128, Succursale Centre-ville,

Montreal, Quebec, H3C 3J7 Canada

Email: [email protected]

at MINNESOTA STATE UNIV MANKATO on August 6,

2013jfn.sagepub.comDownloaded from

http://jfn.sagepub.com/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/busi604discussionassignmentinstructionsinstructionsthest-220922010340-40653e53/75/BUSI-604Discussion-Assignment-InstructionsInstructionsThe-st-329-2048.jpg)

![http://jfn.sagepub.com/

482 Journal of Family Nursing 15(4)

References

Bell. J. M. (2008). The Family Nursing Unit, University of

Calgary: Reflections on 25

years of clinical scholarship (1982-2007) and closure

announcement [Editorial].

Journal of Family Nursing, 14, 275-288.

Bell, J. M., & Wright, L. M. (2007). La recherche sur la

pratique des soins infirmiers

à la famille [Research on family interventions]. In F. Duhamel

(Ed.), La santé et la

famille: Une approche systémique en soins infirmiers [Families

and health: A sys-

temic approach in nursing care] (2nd ed., pp. 87-105). Montreal,

Quebec, Canada:

Gaëtan Morin Editeur. (An English version of this book chapter

available for public

access on DSpace at the University of Calgary Library:

https://dspace.ucalgary.ca/](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/busi604discussionassignmentinstructionsinstructionsthest-220922010340-40653e53/75/BUSI-604Discussion-Assignment-InstructionsInstructionsThe-st-394-2048.jpg)

![handle/1880/44060)

Clayton, J. M., Butow, P. N., & Tattersall, M. H. N. (2005).

When and how to initi-

ate discussion about prognosis and end-of-life issues with

terminally ill patients.

Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 30, 132-144.

Daneault, S. (2006). Souffrance et médecine [Suffering and

medicine]. Quebec City,

Quebec, Canada: Les Presses de l’Université du Québec.

Doane, G. H., & Varcoe, C. (2005). Family nursing as relational

inquiry. Philadel-

phia: Lippincott Williams &Wilkins.

Duhamel, F. (2007). La santé et la famille. Une approche

sytémique en soins infirmiers

[Families and health: A systemic approach in nursing care] (2nd

ed.). Montreal,

Quebec, Canada: Gaëtan Morin Éditeur.

Duhamel, F., & Dupuis, F. (2004). Guaranteed returns:

Investing in conversations

with families of cancer patients. Clinical Journal of Oncology](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/busi604discussionassignmentinstructionsinstructionsthest-220922010340-40653e53/75/BUSI-604Discussion-Assignment-InstructionsInstructionsThe-st-395-2048.jpg)

![Nursing, 8, 68-71.

Duhamel, F., & Talbot, L. (2004). A constructivist evaluation of

family interventions

in cardiovascular nursing practice. Journal of Family Nursing,

10, 12-32.

Dupuis, F. (2007). Modélisation systémique de la transition

pour des familles ayant un

adolescent atteint de fibrose kystique en phase pré-transfert vers

l’établissement

adulte [A systemic model of transition for families who have an

adolescent living

with cystic fibrosis, at the pre-transfer stage]. Unpublished

doctoral dissertation,

University of Montreal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Eriksson, M., & Svedlund, M. (2006). “The intruder”: Spouses’

narratives about life

with a chronically ill partner. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15,

324-333.

Gottlieb, L. (2007). A tribute to the Calgary Family Nursing

Unit: Lessons that go

beyond family nursing [Editorial]. Canadian Journal of Nursing](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/busi604discussionassignmentinstructionsinstructionsthest-220922010340-40653e53/75/BUSI-604Discussion-Assignment-InstructionsInstructionsThe-st-396-2048.jpg)

![the 15 (or less) family

interview influence family nursing practice? Journal of Family

Nursing, 13, 157-178.

Morasz, L. (1999). Le soignant face à la souffrance [The carer

confronted by suffer-

ing]. Paris: Dunod.

Moules, N. J. (2002). Nursing on paper: Therapeutic letters in

nursing practice. Nurs-

ing Inquiry, 9, 104-113.

Order of Nurses of Quebec. (2001, May 14). Vision

contemporaine de l’exercice

infirmier au Québec (La). [A contemporary vision of nursing

practice in Quebec].

Report presented to the Ministerial Working Group on Health

Care Professions

and Human Relations. Montreal, Quebec, Canada: Author.

Petersen, A. (2006). The best experts: The narratives of those

who have a chronic

condition. Social Science & Medicine, 63, 32-42.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/busi604discussionassignmentinstructionsinstructionsthest-220922010340-40653e53/75/BUSI-604Discussion-Assignment-InstructionsInstructionsThe-st-399-2048.jpg)

![guide to family assess-

ment and intervention (5th ed.). Philadelphia: F. A. Davis.

Wright, L. M., & Bell, J. M. (2009). Beliefs and illness: A

model for healing. Calgary,

Alberta, Canada: 4th Floor Press.

Bios

Fabie Duhamel, RN, PhD, is a professor at the Faculty of

Nursing, University of

Montreal, Canada, where she founded a Family Nursing Unit for

clinical and educa-

tional purposes within the graduate nursing program. Her

research activities focus on

Family Systems Nursing and chronic illness and on knowledge

transfer. Her recent

publications include La santé et la famille. Une approche

systémique en soins infirm-

iers [Families and Health: A Systemic Nursing Approach in

Nursing Care] (2007); “A

Qualitative Evaluation of a Family Nursing Intervention” in

Clinical Nurse Special-

ist: Journal for Advanced Nursing Practice (2007, with F.

Dupuis, M. A. Reidy, &](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/busi604discussionassignmentinstructionsinstructionsthest-220922010340-40653e53/75/BUSI-604Discussion-Assignment-InstructionsInstructionsThe-st-402-2048.jpg)