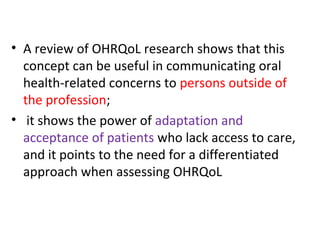

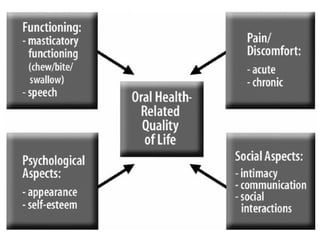

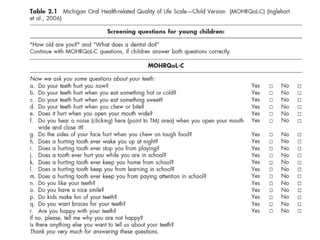

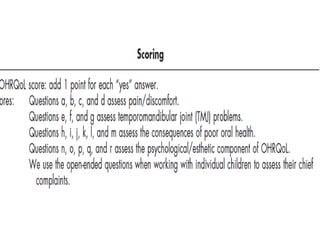

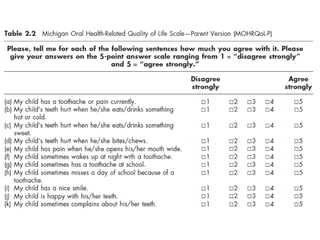

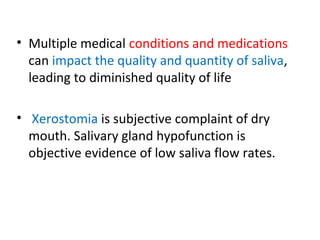

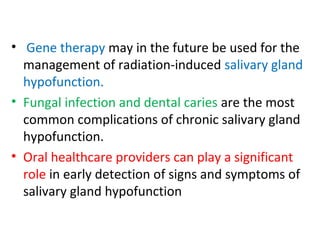

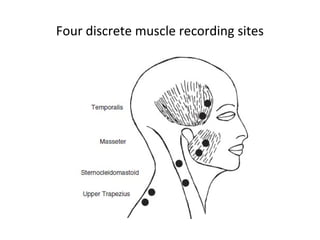

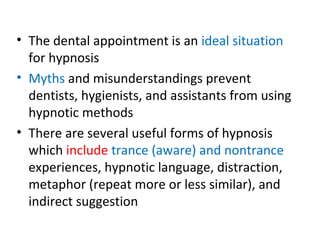

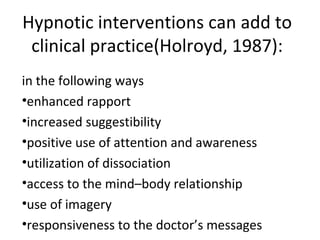

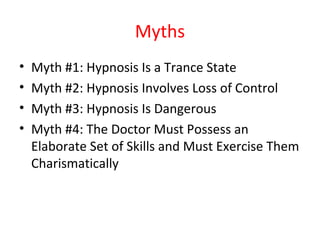

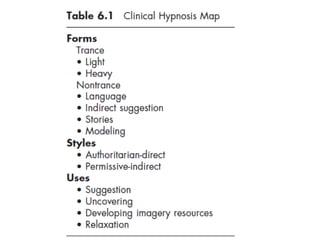

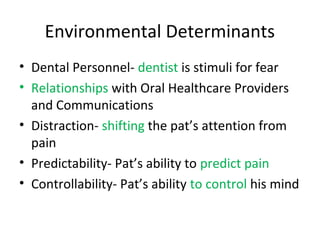

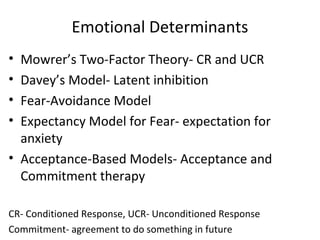

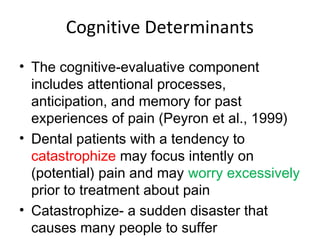

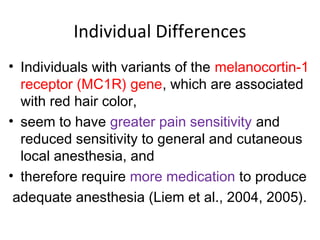

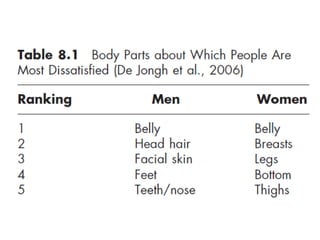

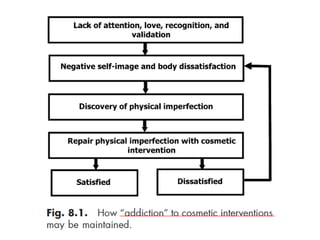

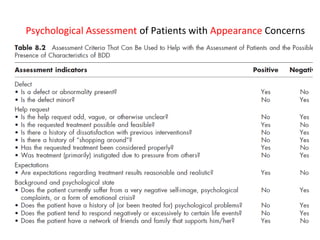

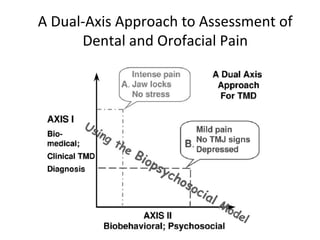

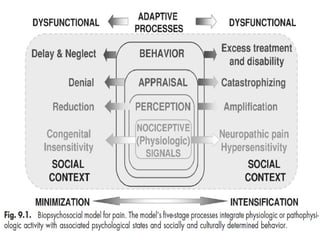

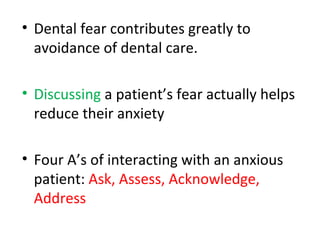

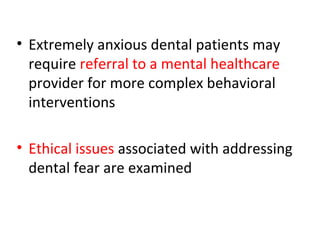

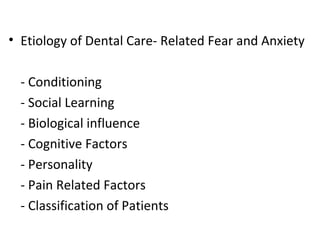

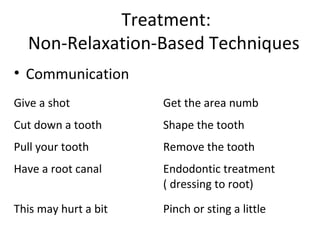

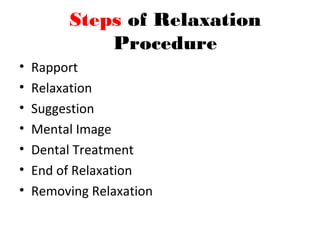

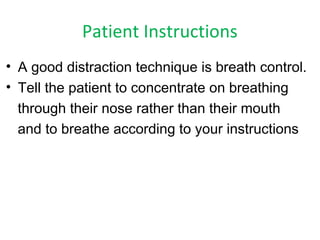

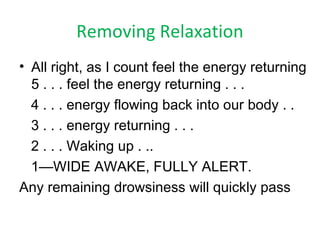

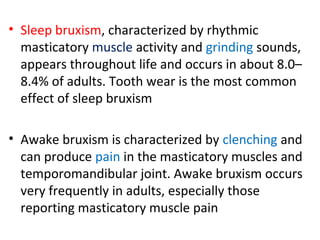

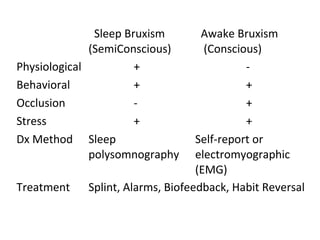

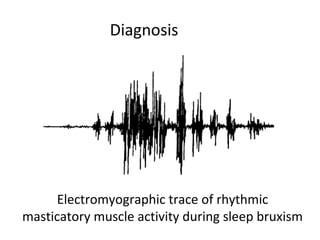

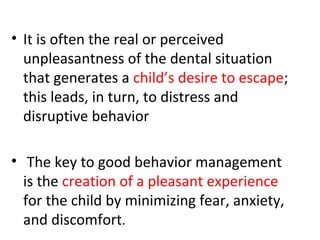

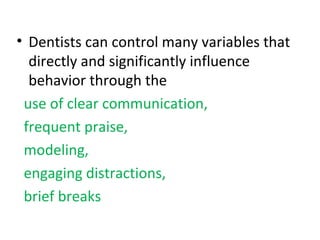

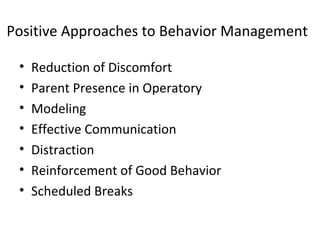

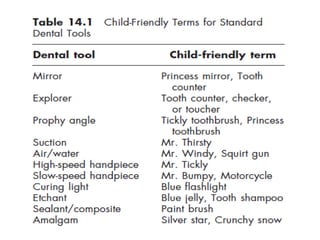

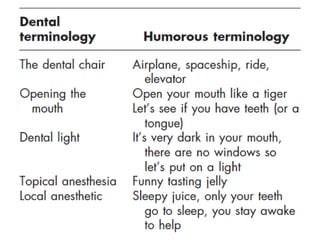

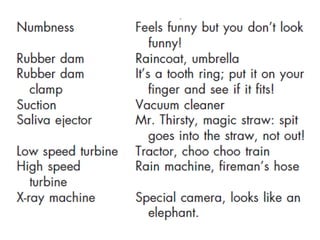

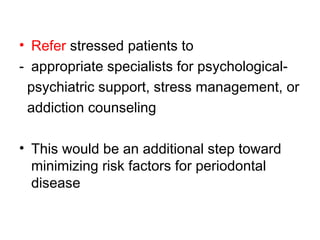

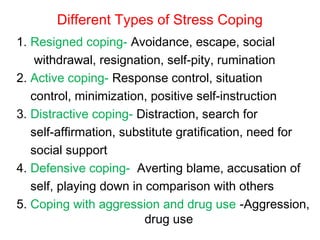

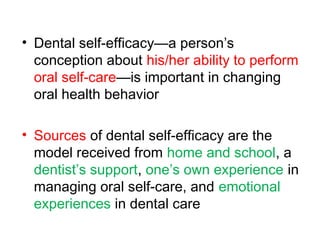

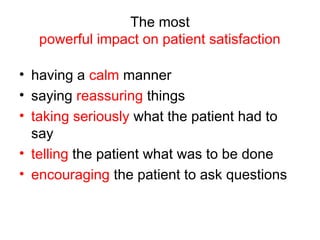

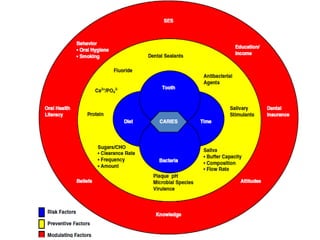

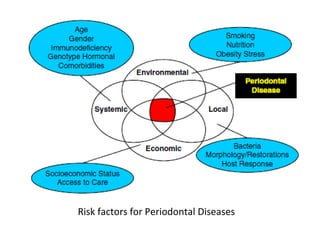

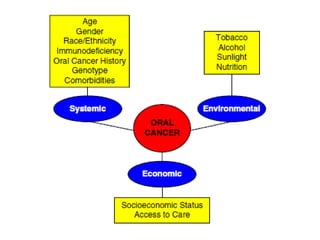

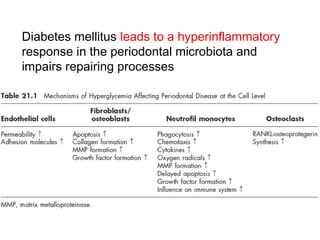

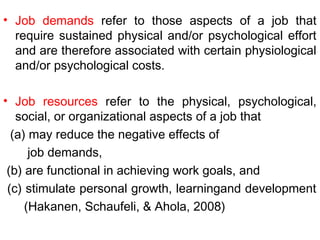

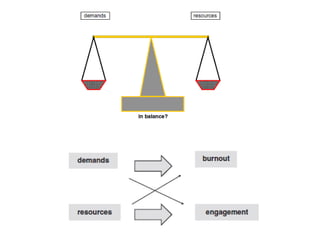

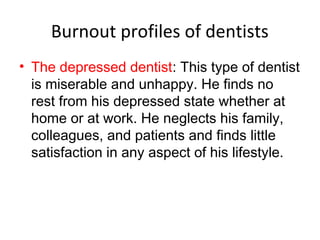

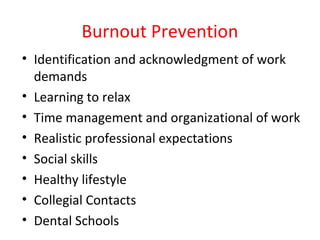

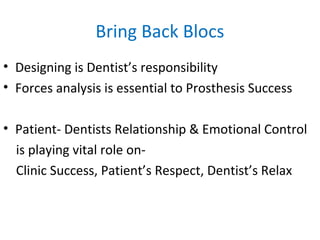

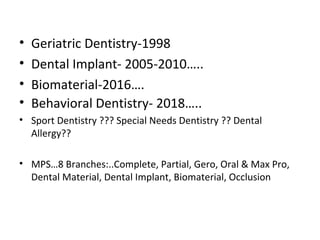

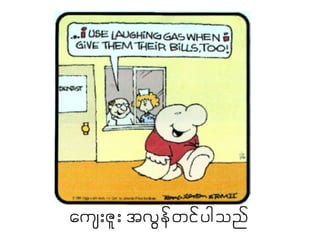

The document discusses behavioral dentistry, emphasizing the importance of understanding human behavior in preventing oral diseases and enhancing patient care. It covers various topics including the cultural competence of dental professionals, the impact of oral health on quality of life, and strategies for managing patient anxiety and pain during dental procedures. Key insights include the role of psychosocial factors in dental health and techniques such as hypnosis and biofeedback for improving patient experiences.