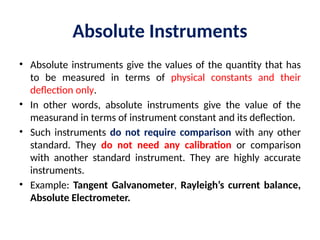

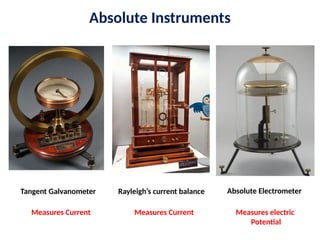

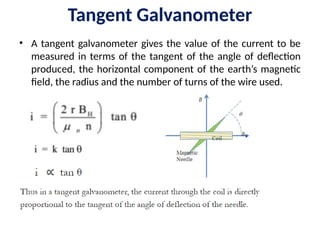

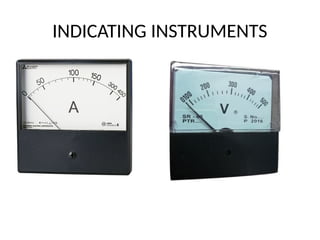

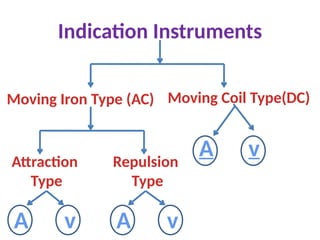

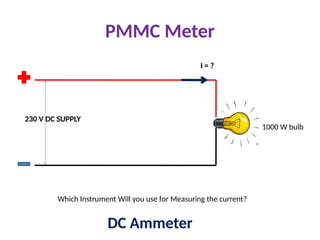

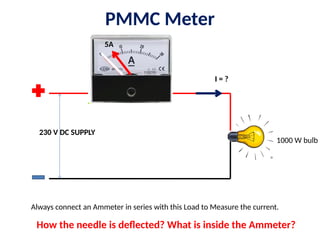

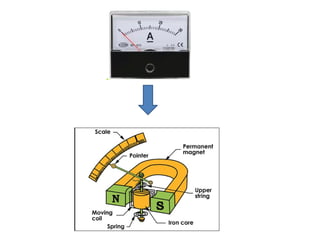

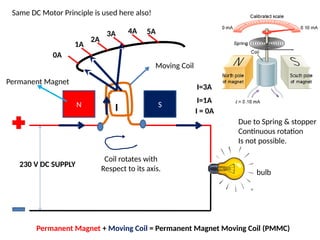

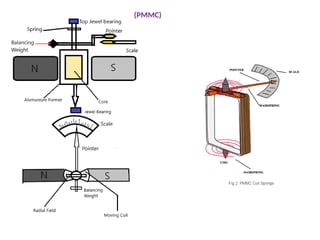

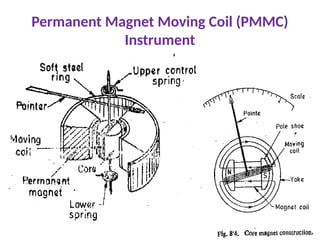

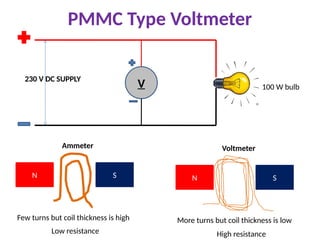

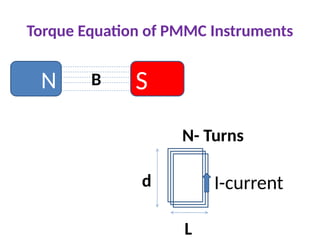

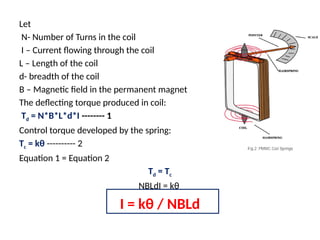

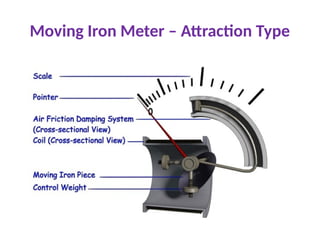

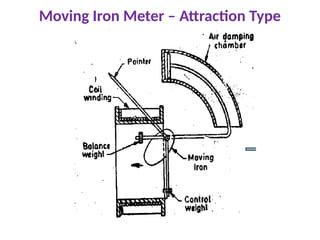

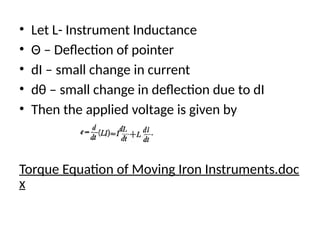

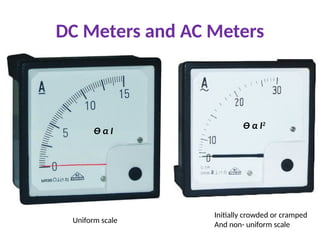

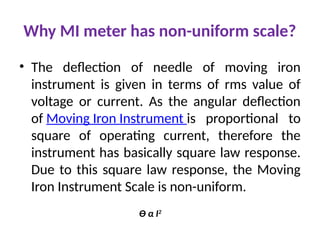

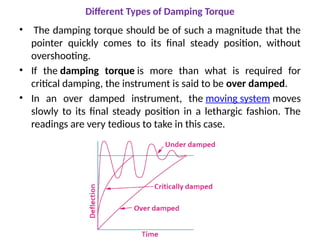

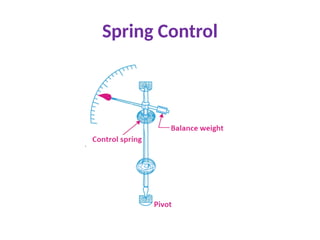

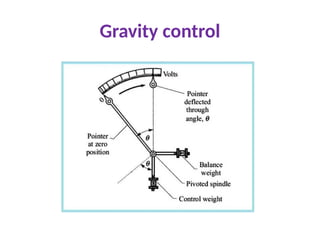

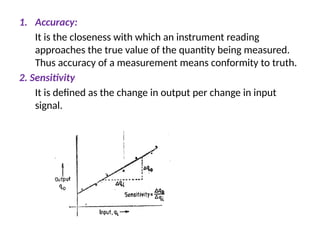

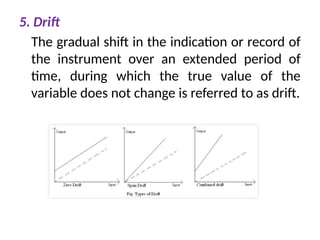

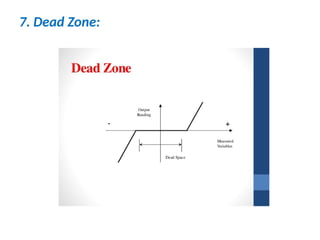

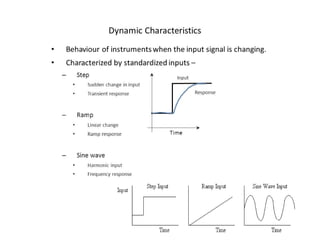

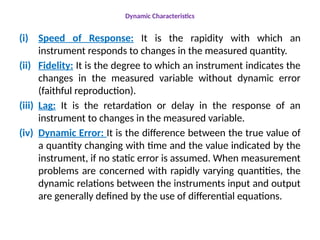

The document discusses various types of measuring instruments, distinguishing between absolute and secondary instruments, and detailing their principles of operation, including examples like ammeters and voltmeters. It elaborates on the concepts of deflecting, controlling, and damping torques, explaining how these forces influence the performance of instruments, alongside types of errors affecting measurement accuracy. Additionally, it covers the characteristics of measurement as well as static and dynamic behavior, highlighting the importance of calibration and potential sources of error.