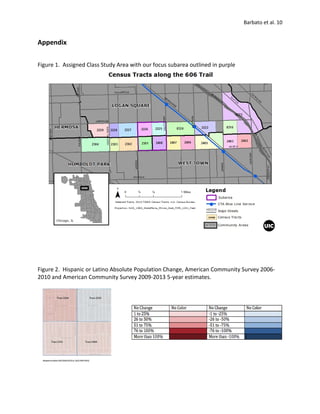

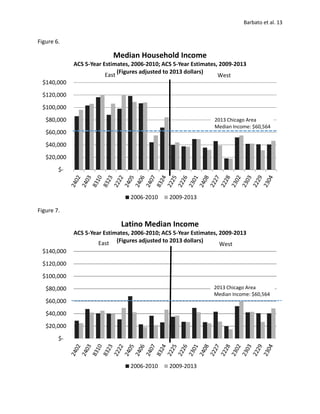

This document summarizes a research report on neighborhood changes along Chicago's 606 trail between 2000-2013. The report analyzes census data from 4 tracts near the trail. It finds that while the white population initially increased, Latino populations have been increasing again in 3 of the 4 tracts since 2009. Household incomes are lower in western tracts near the trail. The report examines theories of neighborhood change like Latino uplift and invasion-succession to understand the demographic shifts occurring. Mobility data suggests some degree of displacement in western tracts following the housing crisis. The report also surveys commercial changes on a nearby street and finds signs of businesses catering to newer, wealthier residents moving in.