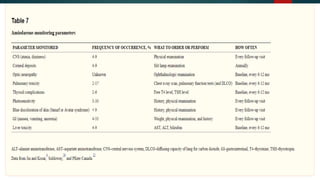

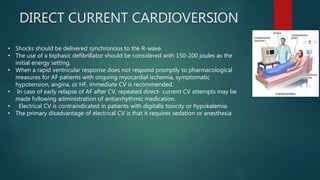

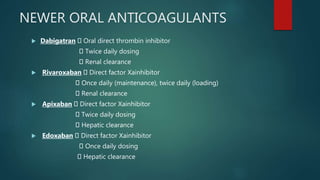

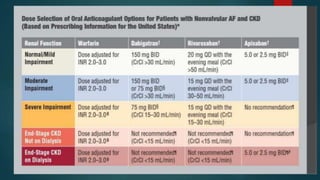

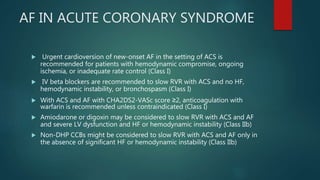

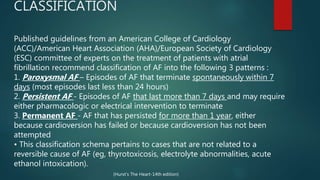

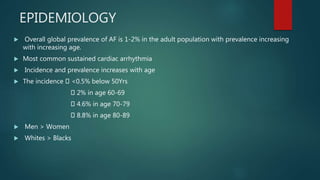

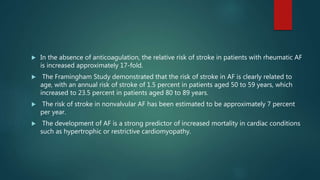

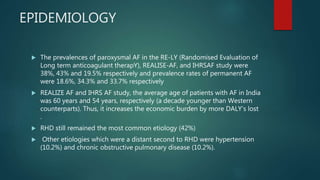

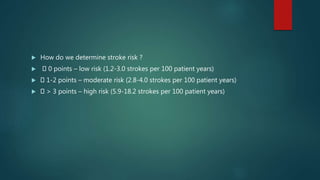

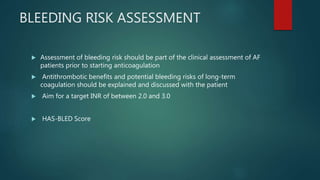

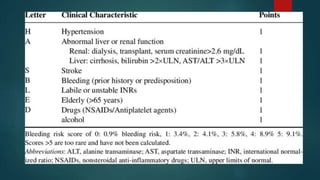

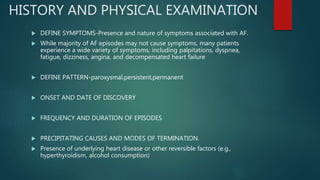

This document provides an overview of atrial fibrillation (AF). It begins with the basic electrophysiology of the heart and defines AF. It describes the classification, causes, pathophysiology and epidemiology of AF. It discusses the risks of stroke and methods for assessing stroke risk, including various risk scores. The document outlines the guidelines for managing AF, including treatment options and newer oral anticoagulants. It provides details on evaluating a patient with AF through history, physical exam, ECG and echocardiogram.

![ADDITIONAL TESTING

Six-minute walk test (if the adequacy of rate control is in question) Exercise

test (if the adequacy of rate control is in question [permanent atrial

fibrillation])

To reproduce exercise-induced atrial fibrillation

To exclude ischemia before treatment of selected patients with a type IC*

antiarrhythmic drug

Holter monitor test or event recording (if diagnosis of the type of

arrhythmia is in question) to evaluate rate control](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/atrialfibrillation-220410042407/85/ATRIAL-FIBRILLATION-pptx-35-320.jpg)