This document provides information about the ninth edition of Apley's System of Orthopaedics and Fractures. It lists the principal authors and contributors, and provides a brief preface and acknowledgements. The book is dedicated to the authors' students, trainees, patients, wives, children and grandchildren. It was first published in 1959 and this ninth edition was published in 2010 by Hodder Arnold.

![iv

First published in Great Britain in 1959 by Butterworths Medical Publications

Second edition 1963

Third edition 1968

Fourth edition 1973

Fifth edition 1977

Sixth edition 1982

Seventh edition published in 1993 by Butterworth Heineman.

Eight edition published in 2001 by Arnold.

This ninth edition published in 2010 by

Hodder Arnold, an imprint of Hodder Education, an Hachette UK Company,

338 Euston Road, London NW1 3BH

http://www.hodderarnold.com

© 2010 Solomon, Warwick, Nayagam

All rights reserved. Apart from any use permitted under UK copyright law, this publica-

tion may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, with

prior permission in writing of the publishers or in the case of reprographic production, in

accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. In the

United Kingdom such licences are issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency:

90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP

Whilst the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the

date of going to press, neither the author[s] nor the publisher can accept any legal

responsibility or liability for any errors or omissions that may be made. In particular (but

without limiting the generality of the preceding disclaimer) every effort has been made to

check drug dosages; however it is still possible that errors have been missed. Furthermore,

dosage schedules are constantly being revised and new side-effects recognized. For these

reasons the reader is strongly urged to consult the drug companies’ printed instructions

before administering any of the drugs recommended in this book.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN-13 978 0 340 942 055

ISBN-13 [ISE] 978 0 340 942 086 (International Students’ Edition, restricted

territorial availability)

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Commissioning Editor: Gavin Jamieson

Project Editor: Francesca Naish

Production Controller: Joanna Walker

Cover Designer: Helen Townson

Indexer: Laurence Errington

Additional editorial services provided by

Naughton Project Management.

Cover image © Linda Bucklin/stockphoto.com

Typeset in 10 on 12pt Galliard by Phoenix Photosetting, Chatham, Kent

Printed and bound in India by Replika Press

What do you think about this book? Or any other Hodder Arnold title?

Please visit our website: www.hodderarnold.com](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/apleys-150117201150-conversion-gate02/85/Apley-s-shoulderjt-examination-5-320.jpg)

![Find out details about the patient’s work practices,

travel and recreation: could the disorder be due to a

particular repetitive activity in the home, at work or

on the sportsfield? Is the patient subject to any

unusual occupational strain? Has he or she travelled to

another country where tuberculosis is common?

Finally, it is important to assess the patient’s home

circumstances and the level of support by family and

friends. This will help to answer the question: ‘What

has the patient lost and what is he or she hoping to

regain?’

EXAMINATION

In A Case of Identity Sherlock Holmes has the follow-

ing conversation with Dr Watson.

Watson: You appeared to read a good deal upon

[your client] which was quite invisible to me.

Holmes: Not invisible but unnoticed, Watson.

Some disorders can be diagnosed at a glance: who

would mistake the facial appearance of acromegaly or

the hand deformities of rheumatoid arthritis for any-

thing else? Nevertheless, even in these cases systematic

examination is rewarding: it provides information

about the patient’s particular disability, as distinct

from the clinicopathological diagnosis; it keeps rein-

forcing good habits; and, never to be forgotten, it lets

the patient know that he or she has been thoroughly

attended to.

The examination actually begins from the moment

we set eyes on the patient. We observe his or her gen-

eral appearance, posture and gait. Can you spot any

distinctive feature: Knock-knees? Spinal curvature? A

short limb? A paralysed arm? Does he or she appear to

be in pain? Do their movements look natural? Do they

walk with a limp, or use a stick? A tell-tale gait may

suggest a painful hip, an unstable knee or a foot-drop.

The clues are endless and the game is played by every-

one (qualified or lay) at each new encounter through-

out life. In the clinical setting the assessment needs to

be more focussed.

When we proceed to the structured examination,

the patient must be suitably undressed; no mere

rolling up of a trouser leg is sufficient. If one limb is

affected, both must be exposed so that they can be

compared.

We examine the good limb (for comparison), then

the bad. There is a great temptation to rush in with

both hands – a temptation that must be resisted. Only

by proceeding in a purposeful, orderly way can we

avoid missing important signs.

Alan Apley, who developed and taught the system

used here, shied away from using long words where

short ones would do as well. (He also used to say ‘I’m

neither an inspector nor a manipulator, and I am defi-

nitely not a palpator’.) Thus the traditional clinical

routine, inspection, palpation, manipulation, was

replaced by look, feel, move. With time his teaching has

been extended and we now add test, to include the

special manoeuvres we employ in assessing neurolog-

ical integrity and complex functional attributes.

Look

Abnormalities are not always obvious at first sight. A

systematic, step by step process helps to avoid mis-

takes.

Shape and posture The first things to catch one’s

attention are the shape and posture of the limb or the

body or the entire person who is being examined. Is

the patient unusually thin or obese? Does the overall

posture look normal? Is the spine straight or unusu-

ally curved? Are the shoulders level? Are the limbs

normally positioned? It is important to look for defor-

mity in three planes, and always compare the affected

part with the normal side. In many joint disorders and

in most nerve lesions the limb assumes a characteristic

posture. In spinal disorders the entire torso may be

deformed. Now look more closely for swelling or

wasting – one often enhances the appearance of the

other! Or is there a definite lump?

Skin Careful attention is paid to the colour, quality

and markings of the skin. Look for bruising, wounds

and ulceration. Scars are an informative record of the

past – surgical archaeology, so to speak. Colour

reflects vascular status or pigmentation – for example

the pallor of ischaemia, the blueness of cyanosis, the

redness of inflammation, or the dusky purple of an old

bruise. Abnormal creases, unless due to fibrosis, sug-

gest underlying deformity which is not always obvi-

ous; tight, shiny skin with no creases is typical of

oedema or trophic change.

GENERALORTHOPAEDICS

6

1

1.3 Look Scars often give clues to the previous history.

The faded scar on this patient’s thigh is an old operation

wound – internal fixation of a femoral fracture. The other

scars are due to postoperative infection; one of the sinuses

is still draining.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/apleys-150117201150-conversion-gate02/85/Apley-s-shoulderjt-examination-25-320.jpg)

![periosteum where mesenchymal cells differentiate into

osteoblasts (intramembranous, or ‘appositional’, bone

formation) and old bone is removed from the inside of

the cylinder by osteoclastic endosteal resorption.

Intramembranous periosteal new bone formation

also occurs as a response to periosteal stripping due to

trauma, infection or tumour growth, and its appear-

ance is a useful radiographic pointer.

BONE RESORPTION

Bone resorption is carried out by the osteoclasts under

the influence of stromal cells (including osteoblasts)

and both local and systemic activators. Although it has

long been known that PTH promotes bone resorp-

tion, osteoclasts have no receptor for PTH but the

hormone acts indirectly through its effect on the

vitamin D metabolite 1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol

[1,25(OH)2D3] and osteoblasts.

Proliferation of osteoclastic progenitor cells

requires the presence of an osteoclast differentiating

factor produced by the stromal osteoblasts after stim-

ulation by (for example) PTH, glucocorticoids or

pro-inflammatory cytokines. It is now known that this

‘osteoclast differentiating factor’ is the receptor acti-

vator of nuclear factor-κβ ligand (RANKL for short),

and that it has to bind with a RANK receptor on the

osteoclast precursor in the presence of a macrophage

colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) before full matu-

ration and osteoclastic resorption can begin.

It is thought that osteoblasts first ‘prepare’ the

resorption site by removing osteoid from the bone

surface while other matrix constituents act as osteo-

clast attractors. During resorption each osteoclast

forms a sealed attachment to the bone surface where

the cell membrane folds into a characteristic ruffled

border within which hydrochloric acid and proteolytic

enzymes are secreted. At this low pH minerals in the

matrix are dissolved and the organic components are

destroyed by lysosomal enzymes. Calcium and phos-

phate ions are absorbed into the osteoclast vesicles

from where they pass into the extracellular fluid and,

ultimately, the blood stream.

In cancellous bone this process results in thinning

(and sometimes actual perforation) of existing trabec-

ulae. In cortical bone the cells either enlarge an exist-

ing haversian canal or else burrow into the compact

bone to create a cutting cone – like miners sinking a

new shaft in the ground. During hyperactive bone

resorption these processes are reflected in the appear-

ance of hydroxyproline in the urine and a rise in

serum calcium and phosphate levels.

BONE MODELLING AND REMODELLING

The sequential process of bone resorption and forma-

tion has been likened to sculpting and is, in fact,

known as bone modelling and remodelling. During

growth each bone has continuously to be ‘sculpted’

into the normal shape of that particular part of the

skeleton. How else can a long bone retain its basic

shape as the flared ends are constantly re-formed fur-

ther and further from the midshaft during growth?

The internal architecture of the bone is also subject

to remodelling, not only during growth but through-

out life. This serves several crucial purposes: ‘old

bone’ is continually replaced by ‘new bone’ and in this

way the skeleton is protected from exposure to cumu-

lative loading frequencies and the risk of stress failure;

bone turnover is sensitive to the demands of function

GENERALORTHOPAEDICS

122

7

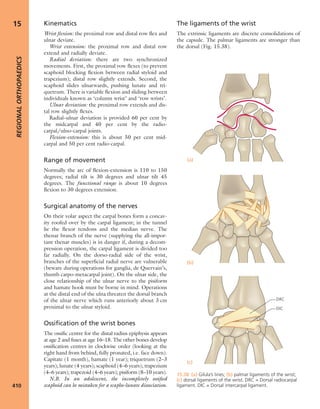

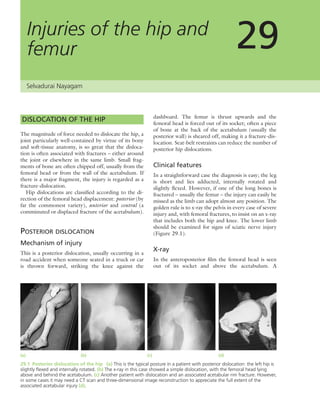

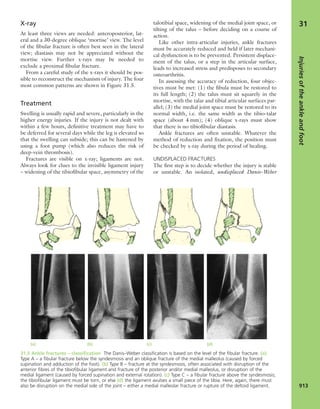

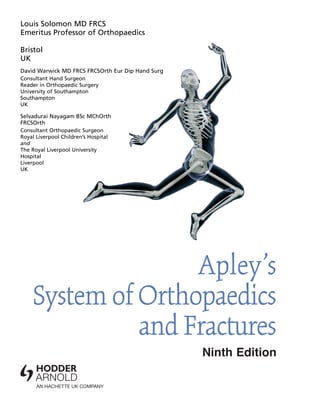

7.4 Blood supply to bone Schematic presentation of

blood supply in tubular bones. (Reproduced from Bullough

PG. Atlas of Orthopaedic Pathology: With Clinical and

Radiological Correlations (2nd edition). Baltimore:

University Park Press, 1985. By kind permission of Dr Peter

G Bullough and Elsevier.)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/apleys-150117201150-conversion-gate02/85/Apley-s-shoulderjt-examination-141-320.jpg)

![between 3 and 3.5 mmol/L, patients may complain of

anorexia, nausea, muscle weakness and fatigue. Those

with severe hypercalcaemia (more than 3.5 mmol/L)

have a plethora of symptoms including abdominal pain,

nausea, vomiting, severe fatigue and depression. In

longstanding cases patients may develop kidney stones

or nephrocalcinosis due to chronic hypercalciuria;

some complain of joint symptoms, due to

chondrocalcinosis. The clinical picture is aptly (though

unkindly) summarized in the old adage ‘moans,

groans, bones and stones’.

There may also be symptoms and signs of the

underlying cause, which should always be sought (in

the vast majority this will be hyperparathyroidism,

metastatic bone disease, myelomatosis, Paget’s disease

or renal failure).

Phosphorus

Apart from its role (with calcium) in the composition

of hydroxyapatite crystals in bone, phosphorus is

needed for many important metabolic processes,

including energy transport and intracellular cell sig-

nalling. It is abundantly available in the diet and is

absorbed in the small intestine, more or less in pro-

portion to the amount ingested; however, absorption

is reduced in the presence of antacids such as alu-

minium hydroxide, which binds phosphorus in the

gut. Phosphate excretion is extremely efficient, but 90

per cent is reabsorbed in the proximal tubules. Plasma

concentration – almost entirely in the form of ionized

inorganic phosphate (Pi) – is normally maintained at

0.9–1.3 mmol/L (2.8–4.0 mg/dL).

The solubility product of calcium and phosphate is

held at a fairly constant level; any increase in the one

will cause the other to fall. The main regulators of

plasma phosphate concentration are PTH and 1,25-

(OH)2D. If the Pi rises abnormally, a reciprocal fall in

calcium concentration will stimulate PTH secretion

which in turn will suppress urinary tubular reabsorp-

tion of Pi, resulting in increased Pi excretion and a fall

in plasma Pi. High Pi levels also result in diminished

1,25-(OH)2D production, causing reduced intestinal

absorption of phosphorus.

In recent years interest has centred on another group

of hormones or growth factors which also have the ef-

fect of suppressing tubular reabsorption of phosphate

independently of PTH. These so-called ‘phospho-

tonins’ are associated with rare phosphate-losing dis-

orders and tumour-induced osteomalacia. Their exact

role in normal physiology is still under investigation.

Magnesium

Magnesium plays a small but important part in min-

eral homeostasis. The cations are distributed in the

cellular and extracellular compartments of the body

and appear in high concentration in bone. Magne-

sium is necessary for the efficient secretion and

peripheral action of parathyroid hormone. Thus, if

hypocalcaemia is accompanied by hypomagnesaemia

it cannot be fully corrected until normal magnesium

concentration is restored.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D, through its active metabolites, is princi-

pally concerned with calcium absorption and transport

and (acting together with PTH) bone remodelling.

Target organs are the small intestine and bone.

Naturally occurring vitamin D (cholecalciferol) is

derived from two sources: directly from the diet and

indirectly by the action of ultraviolet light on the pre-

cursor 7-dehydrocholesterol in the skin. For people

who do not receive adequate exposure to bright sun-

light, the recommended daily requirement for adults is

400–800 IU (10–20 μg) per day – the higher dose for

people over 70 years of age. In most countries this is

obtained mainly from exposure to sunlight; those who

lack such exposure are likely to suffer from vitamin D

deficiency unless they take dietary supplements.

Vitamin D itself is inactive. Conversion to active

metabolites (which function as hormones) takes place

first in the liver by 25-hydroxylation to form 25-

hydroxycholecalciferol [25-OHD], and then in the

kidneys by further hydroxylation to 1,25-dihydroxy-

cholecalciferol [1,25-(OH)2D]. The enzyme responsi-

ble for this conversion is activated mainly by PTH, but

also by other hormones (including oestrogen and pro-

lactin) or by an abnormally low concentration of phos-

phate. If the PTH concentration falls and phosphate

remains high, 25-OHD is converted alternatively to

24,25-(OH)2D which is inactive. On the other hand,

during negative calcium balance production switches

to 1,25-(OH)2D in response to PTH secretion (see

below); the increased 1,25-(OH)2D then helps to

restore the serum calcium concentration.

Metabolicandendocrinedisorders

125

7

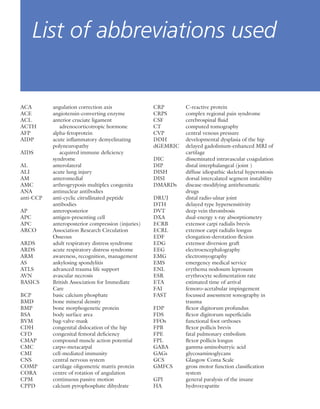

7.7 Vitamin D metabolism The active vitamin D

metabolites are derived either from the diet or by

conversion of precursors when the skin is exposed to

sunlight. The inactive ‘vitamin’ is hydroxylated, first in the

liver and then in the kidney, to form the active metabolites

25-HCC and 1,25-DHCC.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/apleys-150117201150-conversion-gate02/85/Apley-s-shoulderjt-examination-144-320.jpg)

![fatigue and muscle weakness. Patients may develop

polyuria, kidney stones or nephrocalcinosis due to

chronic hypercalciuria. Some complain of joint symp-

toms, due to chondrocalcinosis. Only a minority

(probably less than 10 per cent) present with bone

disease; this is usually generalized osteoporosis rather

than the classic features of osteitis fibrosa, bone cysts

and pathological fractures.

X-rays

Typical x-ray features are osteoporosis (sometimes

including vertebral collapse) and areas of cortical ero-

sion. Hyperparathyroid ‘brown tumours’ should be

considered in the differential diagnosis of atypical

cyst-like lesions of long bones. The classical – and

almost pathognomonic – feature, which should always

be sought, is sub-periosteal cortical resorption of the

middle phalanges. Non-specific features of hypercal-

caemia are renal calculi, nephrocalcinosis and chon-

drocalcinosis.

Biochemical tests

There may be hypercalcaemia, hypophosphataemia

and a raised serum PTH concentration. Serum alka-

line phosphatase is raised with osteitis fibrosa.

Diagnosis

It is necessary to exclude other causes of hypercal-

caemia (multiple myeloma, metastatic disease, sar-

coidosis) in which PTH levels are usually depressed.

Hyperparathyroidism also comes into the differential

diagnosis of all types of osteoporosis and osteomalacia.

Treatment

Treatment is usually conservative and includes ade-

quate hydration and decreased calcium intake. The

indications for parathyroidectomy are marked and

unremitting hypercalcaemia, recurrent renal calculi,

progressive nephrocalcinosis and severe osteoporosis.

Postoperatively there is a danger of severe hypocal-

caemia due to brisk formation of new bone (the ‘hun-

gry bone syndrome’). This must be treated promptly,

with one of the fast-acting vitamin D metabolites.

SECONDARY HYPERPARATHYROIDISM

Parathyroid oversecretion is a predictable response to

chronic hypocalcaemia. Secondary hyperparathy-

roidism is seen, therefore, in various types of rickets

and osteomalacia, and accounts for some of the radi-

ological features in these disorders. Treatment is

directed at the primary condition.

RENAL OSTEODYSTROPHY

Patients with chronic renal failure and lowered

glomerular filtration rate are liable to develop diffuse

bone changes which resemble those of other condi-

tions that affect bone formation and mineralization.

Thus the dominant picture may be that of secondary

hyperparathyroidism [due to phosphate retention,

hypocalcaemia and diminished production of 1,25-

(OH)2D], osteoporosis, osteomalacia or – in

advanced cases – a combination of these. In older

Metabolicandendocrinedisorders

141

7

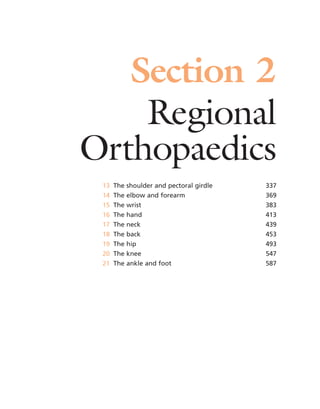

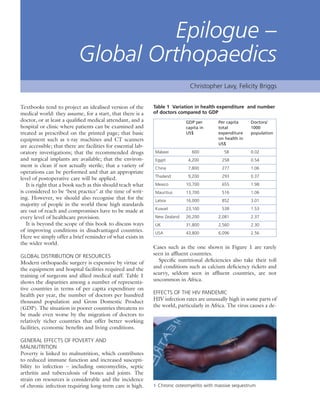

(a) (c)

(b)

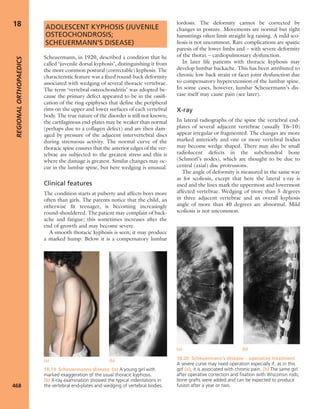

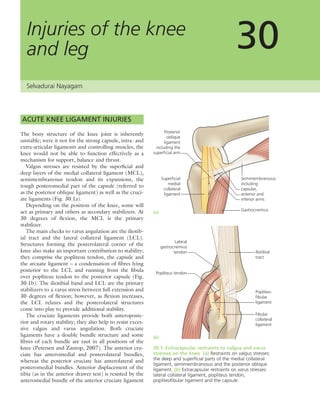

7.18 Renal glomerular

osteodystrophy (a) This young

boy with chronic renal failure

developed severe deformities of

(b) the hips and (c) the knees.

Note the displacement of the

upper femoral epiphyses.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/apleys-150117201150-conversion-gate02/85/Apley-s-shoulderjt-examination-160-320.jpg)