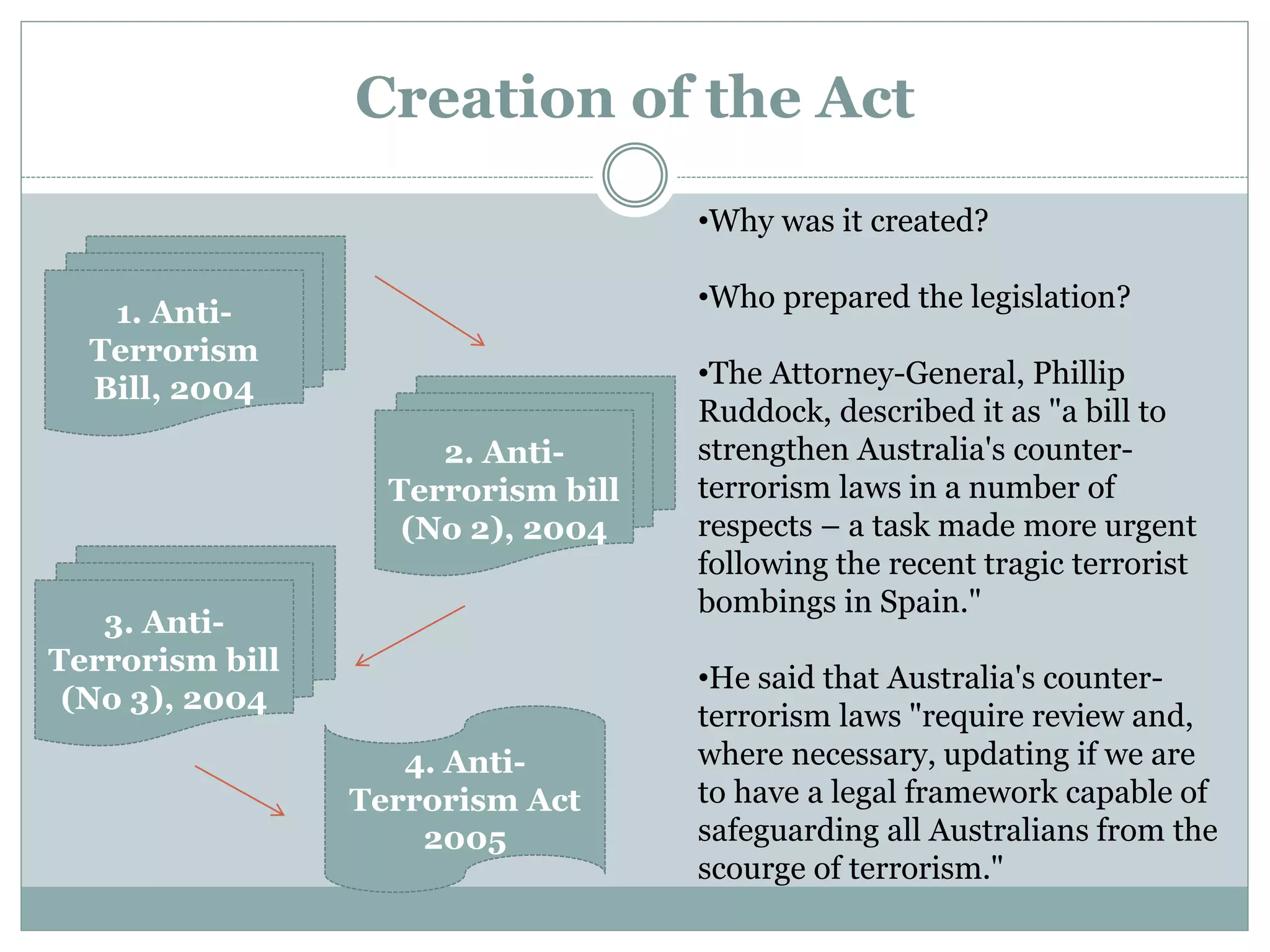

Australia's anti-terrorism laws, established post-2001, include extensive legislative measures aimed at countering terrorism, culminating in the Anti-Terrorism Act 2005. These laws grant authorities significant powers such as preventive detention, control orders, and the ability to search without a warrant, which have raised concerns about civil liberties and targeted profiling of Muslim communities. Personal opinions shared in the document express criticism of the laws for being discriminatory and unjust, highlighting cases like Mohamed Haneef's as indicative of their impact.