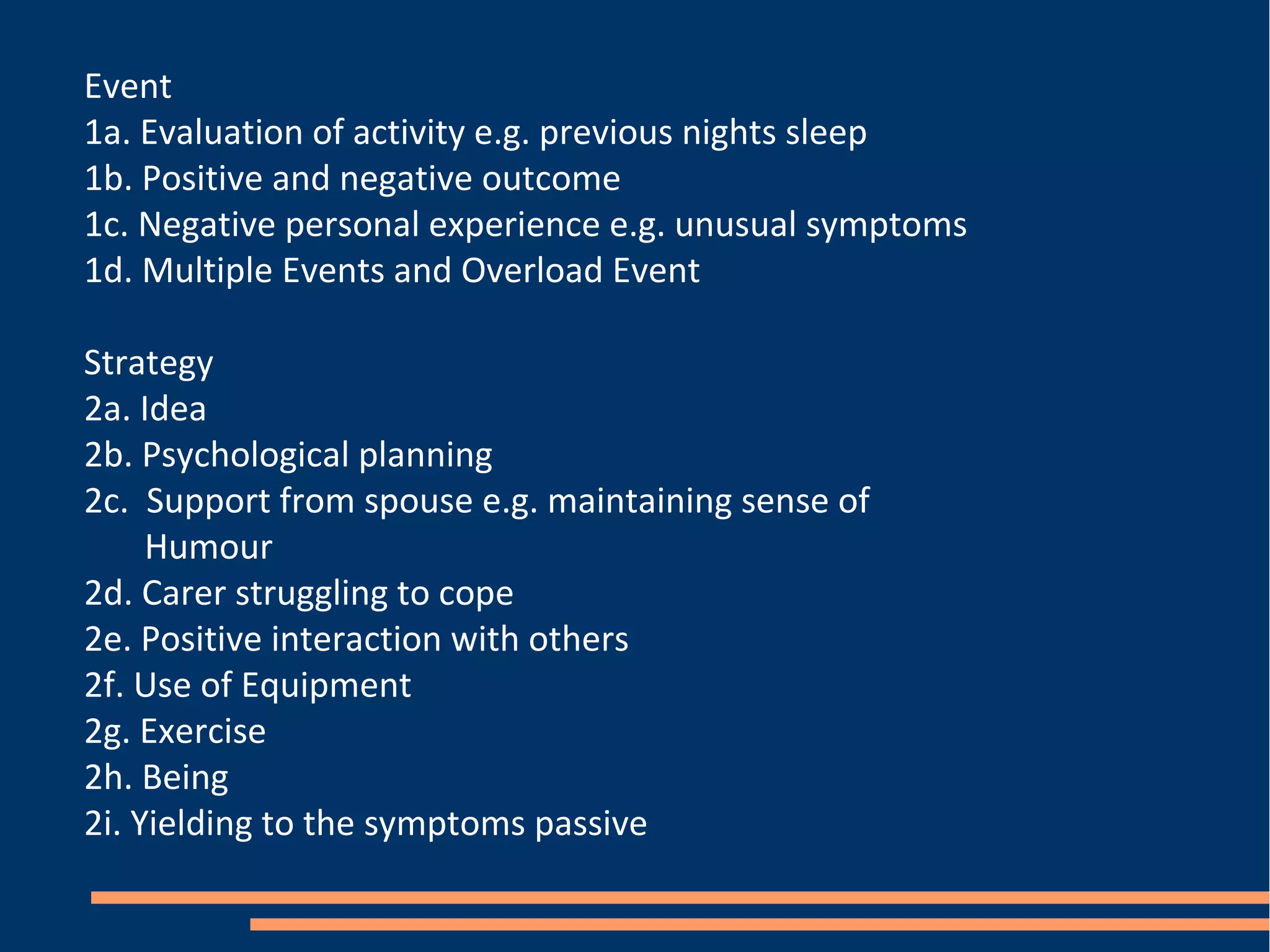

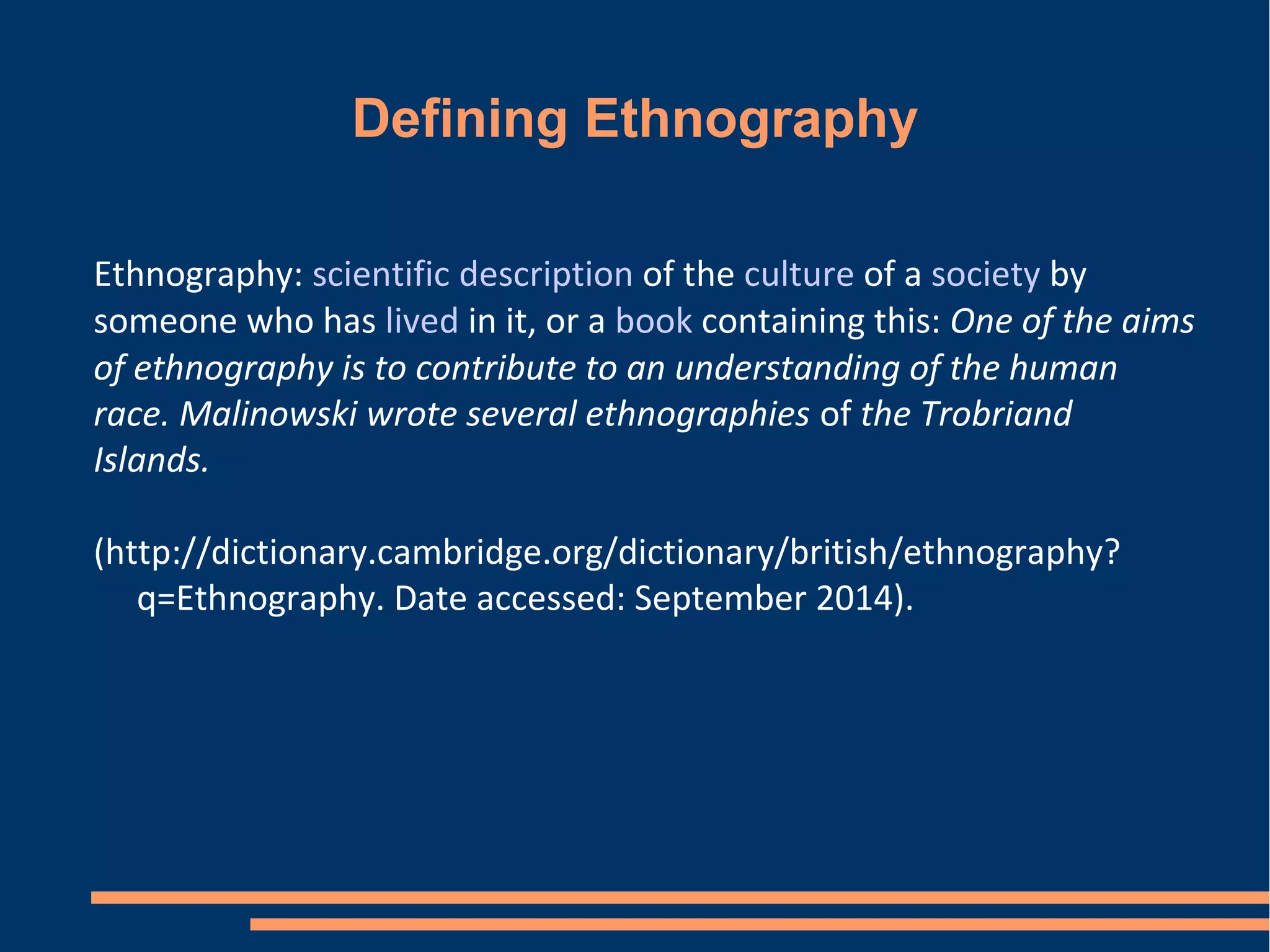

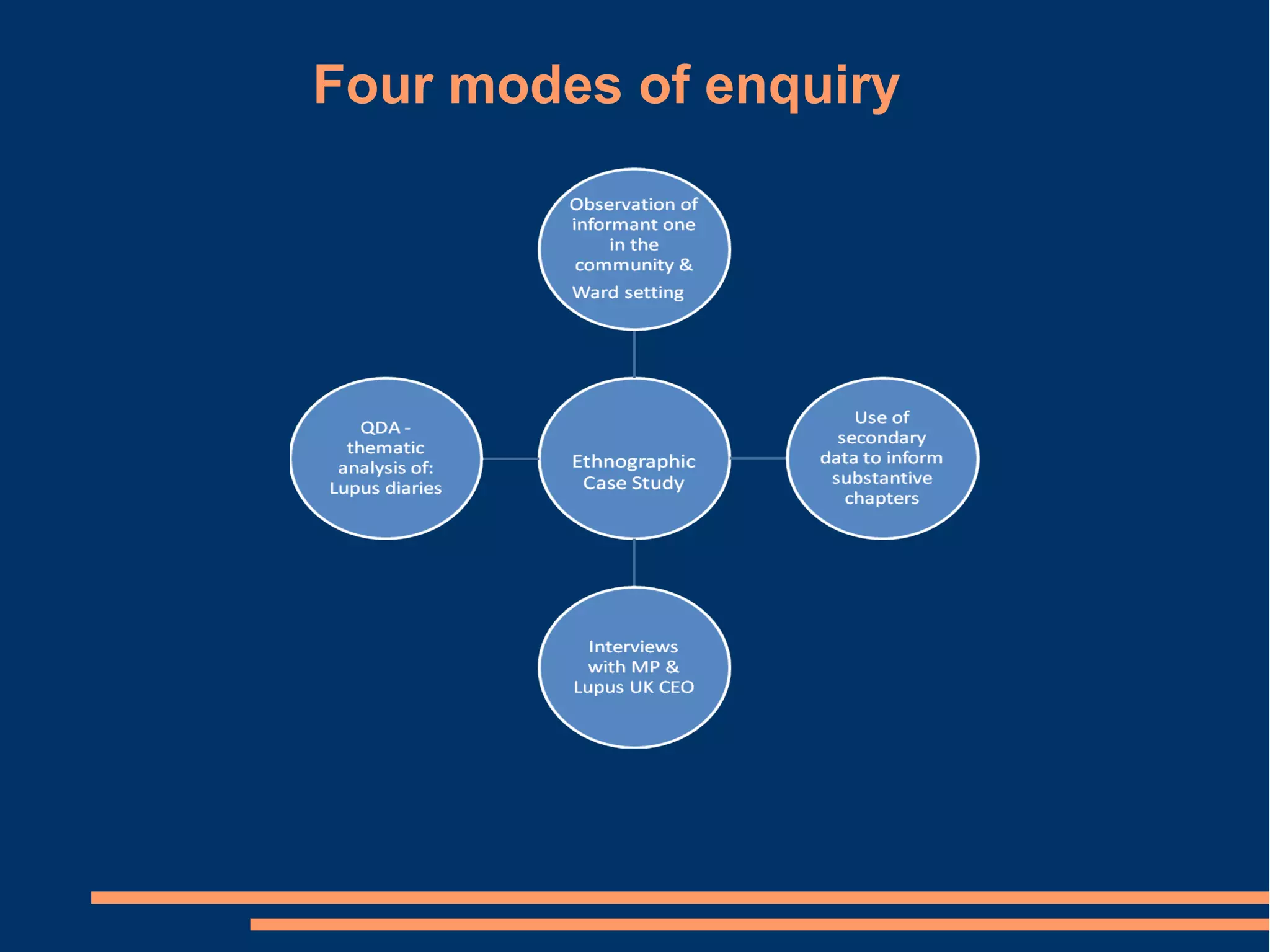

The document discusses the importance of medical professionals understanding patients' cultural backgrounds when assessing their needs. It provides examples of how cultural understanding can reduce prejudice, build mutual respect, and help professionals better understand how different groups experience illnesses. The presentation aims to share the presenter's experience researching the lives of lupus patients, including the challenges faced and methods used like interviews, observation, and qualitative data analysis. It also discusses themes that emerged around daily experiences, strategies for coping, and the social context of dying. The presentation concludes by linking findings to improving care practices.

![Dr. Blaine Robin MSc, PhD

[ Occupational Therapist & Sociologist ]

Undergraduate seminar

All Saints University, Roseau, Dominica

11th

June 2015](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/f58d44d9-5cca-43dc-a828-0790a1f9f401-150626104639-lva1-app6891/75/All-Saints-University-1-2048.jpg)

![The author as ethnographer

As an ethnographer I became the instrument of data collection.

‘[T]he self must not only be offered, it must be accepted’ (Goffman

1979 p 41).

[Implications: Practical examples – professionals that use

immersion/infiltration; the need for reflection, debriefing &

supervision]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/f58d44d9-5cca-43dc-a828-0790a1f9f401-150626104639-lva1-app6891/75/All-Saints-University-11-2048.jpg)