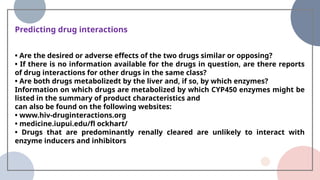

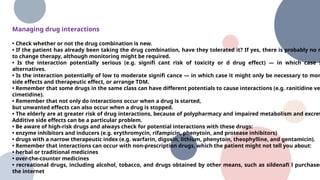

The document discusses adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and drug interactions, highlighting their prevalence, causes, and classifications. It outlines the importance of reporting ADRs, factors affecting their occurrence, and strategies for helping patients understand risks. The document also emphasizes the role of pharmacists in managing these issues and details mechanisms behind drug interactions.