Advanced Paediatric Life Support The Practical Approach Fourth Edition Advanced Life Support Group

Advanced Paediatric Life Support The Practical Approach Fourth Edition Advanced Life Support Group

Advanced Paediatric Life Support The Practical Approach Fourth Edition Advanced Life Support Group

![c

2005 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd

BMJ Books is an imprint of the BMJ Publishing Group Limited, used under licence

Blackwell Publishing, Inc., 350 Main Street, Malden, Massachusetts 02148-5020, USA

Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK

Blackwell Publishing Asia Pty Ltd, 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

The right of the Author to be identified as the Author of this Work has been asserted in accordance with

the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system,

or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or

otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the

prior permission of the publisher.

First published in 1993 by the BMJ Publishing Group

Reprinted in 1994, 1995, 1996

Second edition 1997, reprinted 1998, reprinted with revisions 1998, 1999, 2000

Third edition 2001, second impression 2003, third impression 2003

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Advanced paediatric life support : the practical approach / Advanced Life Support Group;

edited by Kevin Mackway-Jones . . . [et al.].– 4th ed.

p.; cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 0-7279-1847-8

1. Pediatric emergencies. 2. Pediatric intensive care. 3. Life support systems (Critical care)

[DNLM: 1. Emergencies–Child. 2. Emergencies–Infant. 3. Critical Care–Child. 4. Critical

Care–Infant. 5. Wounds and Injuries–therapy–Child. 6. Wounds and Injuries–therapy–Infant.

WS 205 A244 2004] I. Mackway-Jones, Kevin. II. Advanced Life Support Group

(Manchester, England)

RJ370.A326 2004

618.92’0028–dc22

2004021823

ISBN-13: 9780727918475

ISBN-10: 0727918478

Catalogue records for this title are available from the British Library and the Library of Congress

Set by Techbooks, New Delhi, India

Printed and bound in Spain by GraphyCems, Navarra

Commissioning Editor: Mary Banks

Development Editor: Veronica Pock

Production Controller: Kate Charman

For further information on Blackwell Publishing, visit our website:

http://www.blackwellpublishing.com

The publisher’s policy is to use permanent paper from mills that operate a sustainable forestry policy,

and which has been manufactured from pulp processed using acid-free and elementary chlorine-free

practices. Furthermore, the publisher ensures that the text paper and cover board used have met

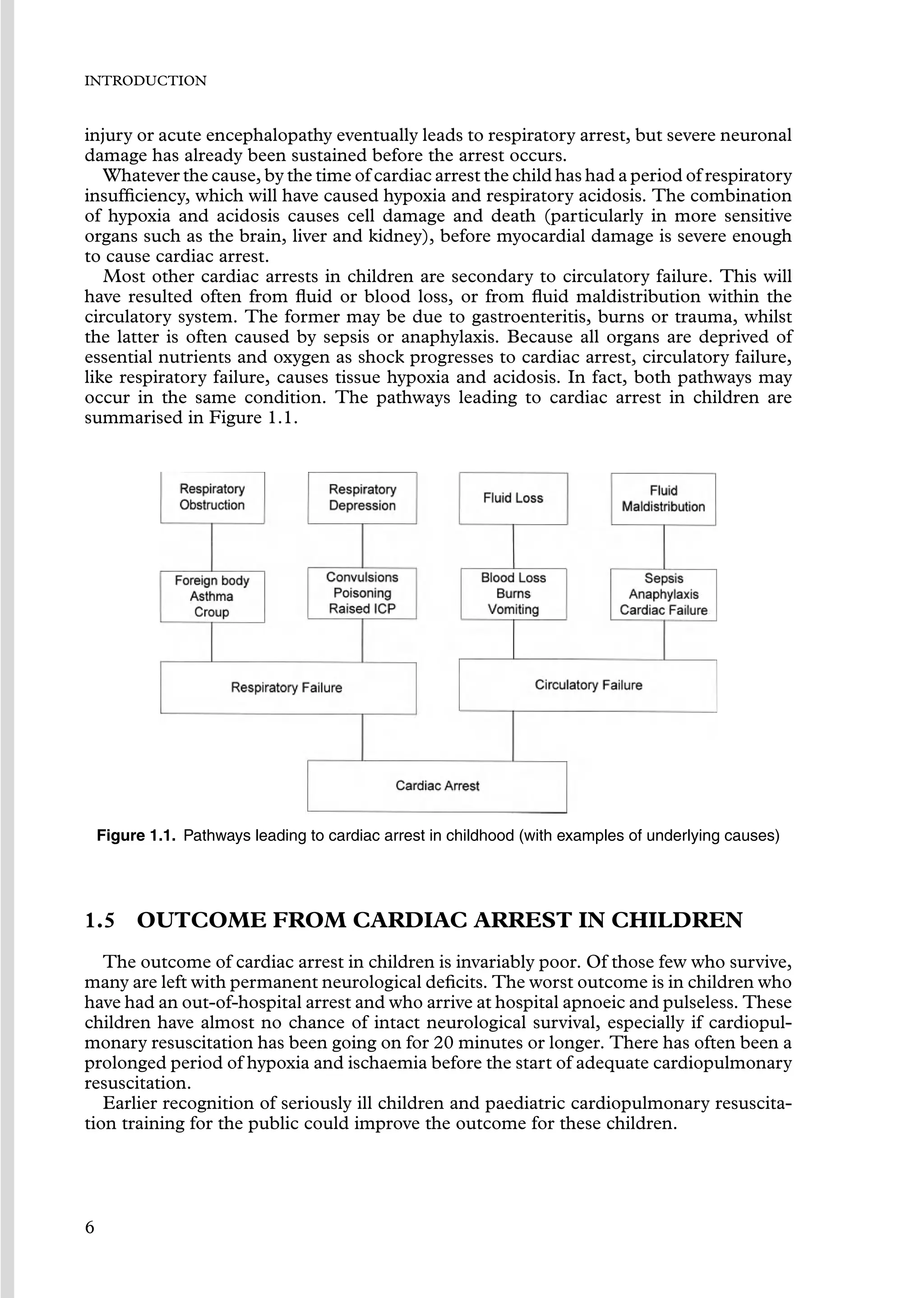

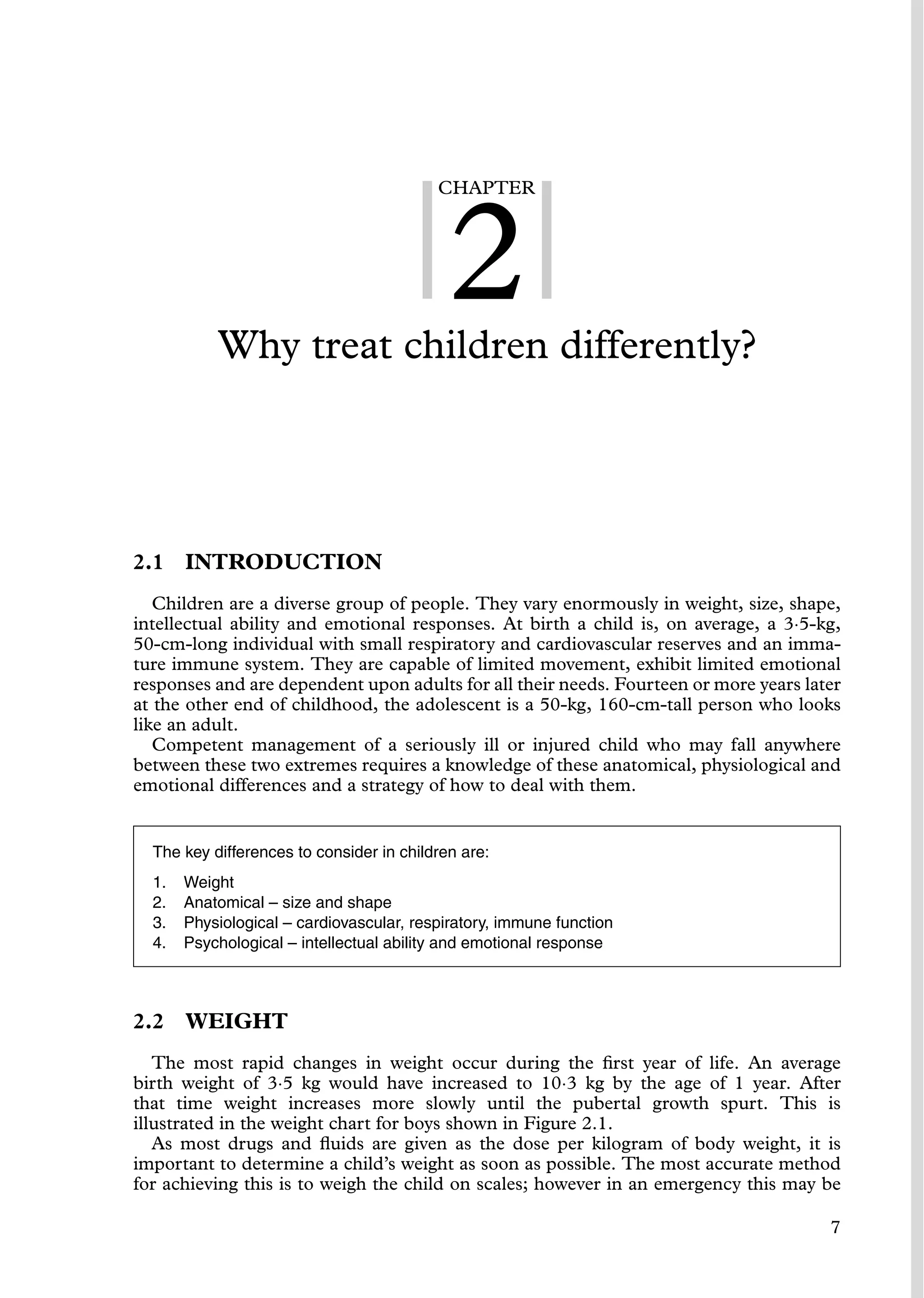

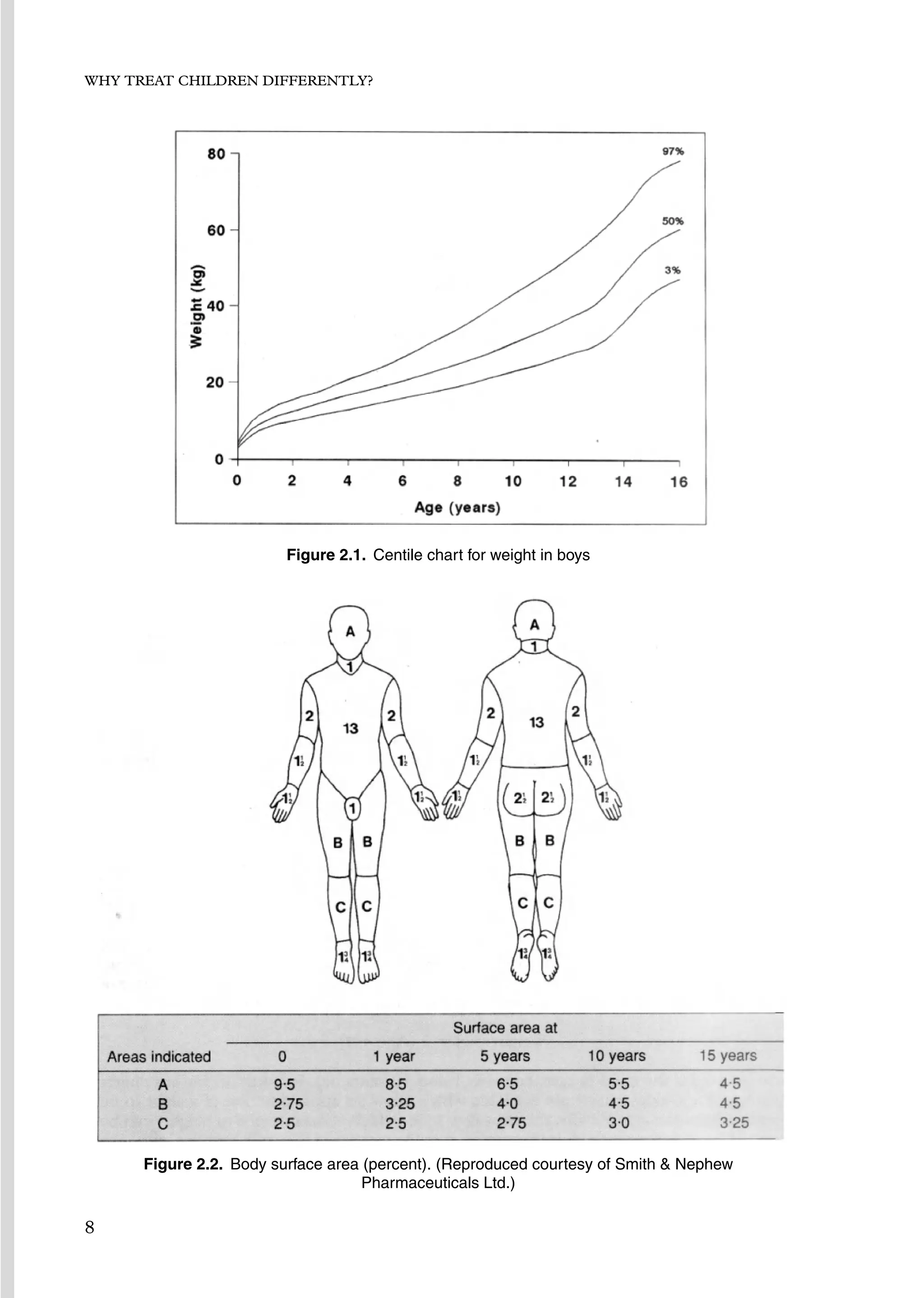

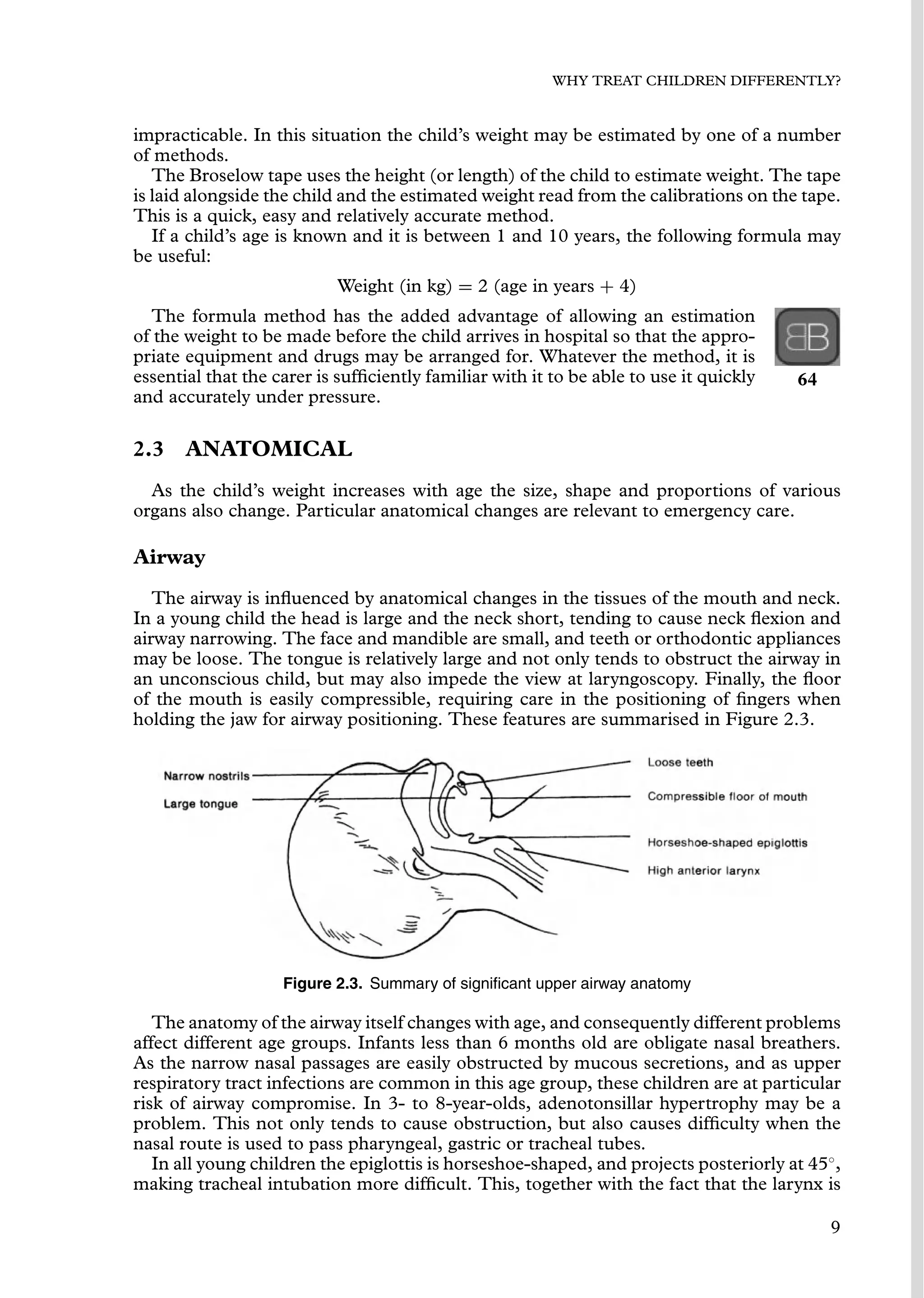

acceptable environmental accreditation standards.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2149320-250530105549-c10570fd/75/Advanced-Paediatric-Life-Support-The-Practical-Approach-Fourth-Edition-Advanced-Life-Support-Group-7-2048.jpg)