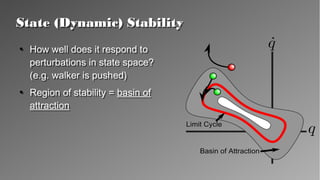

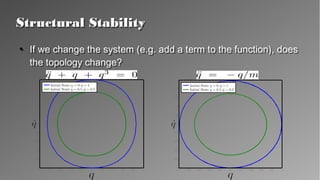

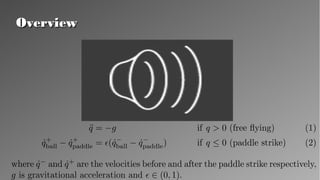

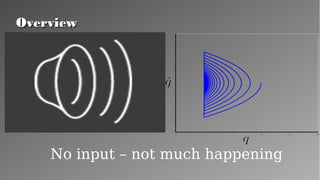

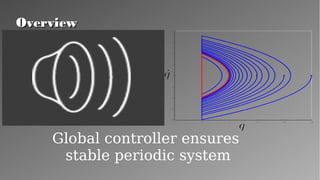

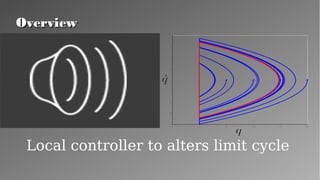

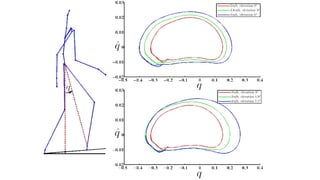

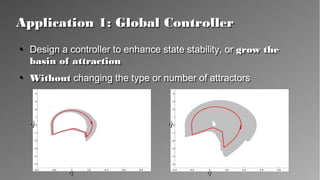

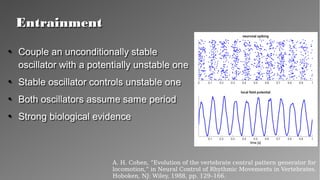

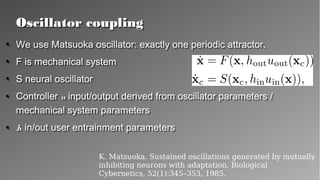

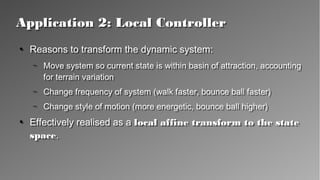

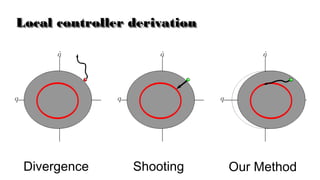

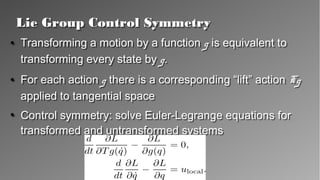

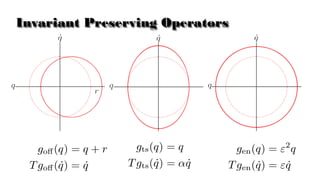

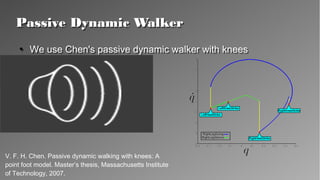

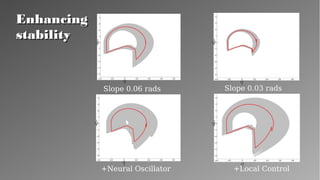

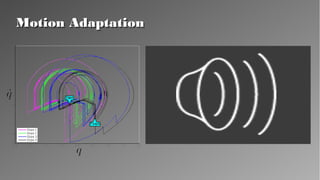

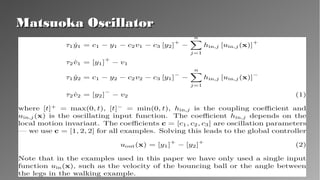

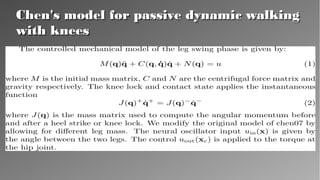

The document presents a theory for motion primitive adaptation, addressing issues in character animation and robotics, emphasizing the importance of energy-efficient, robust, and adaptable controllers. It discusses the role of motion primitives and the central nervous system in locomotion, proposing methods for enhancing stability and performance through local and global control strategies. The findings highlight the significance of preserving motor invariants and suggest potential applications in robotics and rehabilitation.