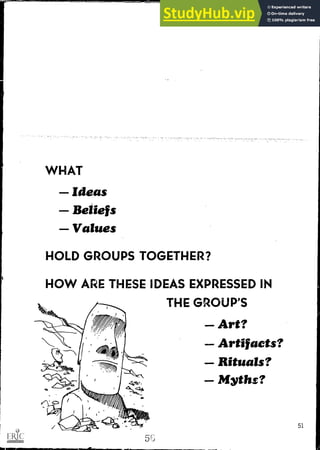

The document provides a rationale for organizing social studies instruction around the study of human groups, suggesting questions for students to investigate about what causes groups to form and change, how groups express their shared beliefs and values through art and rituals, and how groups acquire and maintain control. It argues that studying these types of questions about various human groups requires students to use cognitive skills like observation, classification, hypothesis testing, and determining relationships.

![ONE OF THE BETTER-KNOWN LISTS

OF THINKING SKILLS IS THIS ONE:

1.00 Knowledge [Remembering]

2.00 Comprehension

3.00 Application

4.00 Analysis

5.00 Synthesis

6.00 Evaluation

From,

BENJAMIN S. BLOOM, ED.,

TAXONOMY OF EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES,

COGNITIVE DOMAIN, LONGMANS, GREEN, 1956.

is

13](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/arationaleforsocialstudies-230805211518-293c4108/85/A-Rationale-For-Social-Studies-19-320.jpg)