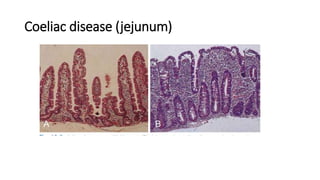

Coeliac disease is an immune-mediated disorder caused by intolerance to gluten, resulting in damage to the small intestine. It is associated with other autoimmune disorders and occurs more commonly in individuals with type 1 diabetes. Clinical features vary depending on age, from failure to thrive in infants to tiredness and weight loss in adults. Investigations include duodenal biopsy showing villous atrophy and antibodies tests. Management involves a lifelong gluten-free diet to aid mucosal healing and correct nutritional deficiencies.