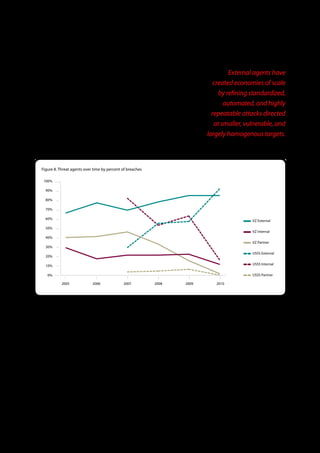

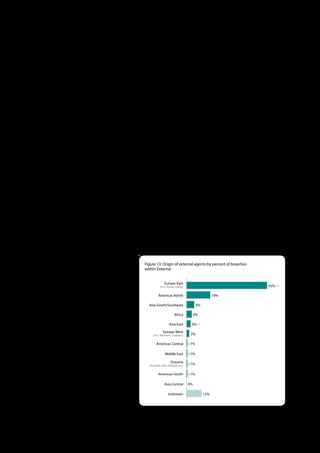

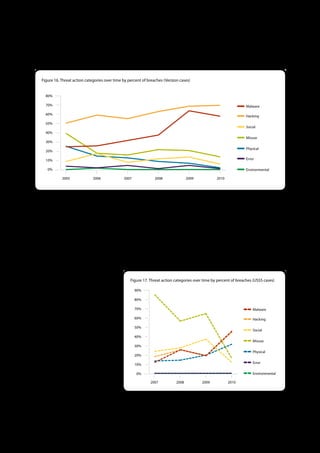

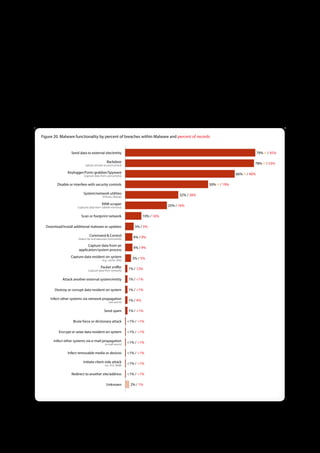

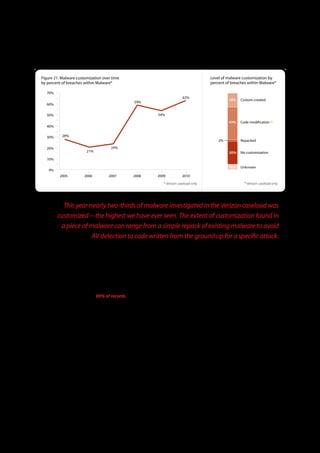

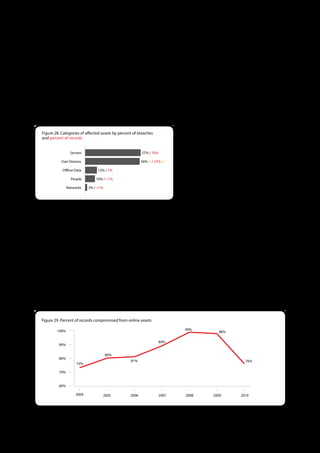

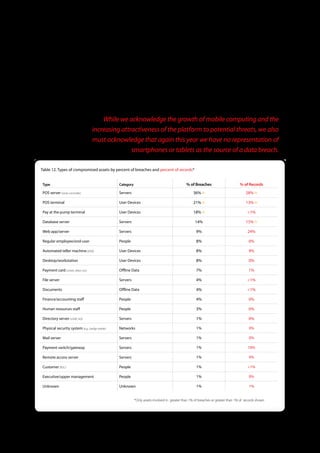

The 2011 Data Breach Investigations Report, conducted by Verizon with the U.S. Secret Service and the Dutch High Tech Crime Unit, analyzed approximately 800 data compromise incidents. This year saw a historic low of under four million compromised records despite the highest number of incidents investigated to date, suggesting a shift in data breach dynamics. Key findings included that 92% of breaches were attributed to external agents and a notable rise in hacking and malware usage in data breaches.