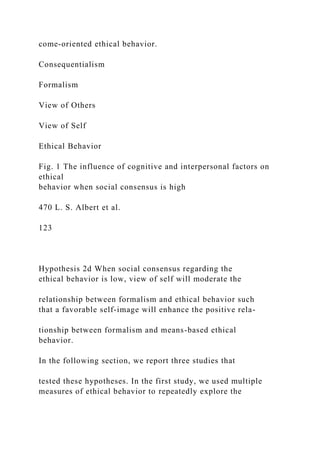

This chapter discusses the multifaceted nature of leadership ethics, differentiating it from singular leadership theories and emphasizing the importance of ethical considerations in leadership situations. It explores the historical context of ethical leadership, Kohlberg's stages of moral development, and various ethical theories, including consequentialism and virtue ethics. The text underscores the significant ethical responsibility leaders hold due to their influence on followers and the organizational values they promote.

![fully explain ethical behavior, and have therefore either

L. S. Albert (&)

College of Business, Colorado State University, Fort Collins,

CO 80523-1275, USA

e-mail: [email protected]

S. J. Reynolds

Foster School of Business, University of Washington, Seattle,

WA 98195, USA

e-mail: [email protected]

B. Turan

Department of Psychology, University of Alabama,

Birmingham, AL 35294, USA

e-mail: [email protected]

123

J Bus Ethics (2015) 130:467–484

DOI 10.1007/s10551-014-2236-2

called for or suggested alternative approaches (e.g., Cohen

2010; Haidt 2001; Hannah et al. 2011; Reynolds 2006b;

Vitell et al. 2013; Weaver et al. 2014). In this vein, several

researchers have argued that a central aspect of ethics is a

‘‘consideration of others’’ (e.g., Brass et al. 1998). These

authors emphasize that interpersonal relationships play an

influential role in explaining individual ethical decision-

making (e.g., attachment theory: Albert and Horowitz](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13leadershipethicsdescriptionthischapterisdifferentfrom-221224050948-cf742ea5/85/13-Leadership-EthicsDescriptionThis-chapter-is-different-from-docx-40-320.jpg)

![ethics not apply to certain roles such that the judgements of

ethics are, in some sense, deemed inappropriate (see the

discussion of the ‘Dirty Hands’ of politicians introduced by

Walzer and discussed in Coady 2008; Mendus 2009).

A. Lawton (&)

Federation University, Ballarat, Australia

e-mail: [email protected]

I. Páez

Universidad de Los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia

e-mail: [email protected]

123

J Bus Ethics (2015) 130:639–649

DOI 10.1007/s10551-014-2244-2

Second, we are interested in what is the relationship

between being a good leader in a moral sense and being an

effective leader; a simple distinction but one that raises

interesting issues. In the literature, there is often a dis-

tinction between moral excellence and technical excellence

(see Ciulla 2005; Price 2008). A different view suggests

that, depending upon our approach to virtue, the two are

compatible and that Machiavelli’s virtú combines both

virtue and skill (see Macaulay and Lawton 2006). A further](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13leadershipethicsdescriptionthischapterisdifferentfrom-221224050948-cf742ea5/85/13-Leadership-EthicsDescriptionThis-chapter-is-different-from-docx-118-320.jpg)

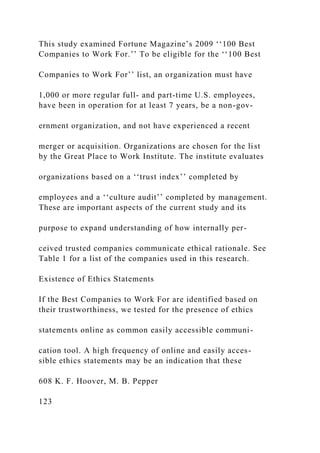

![large part on trust, making trust a crucial factor in the

economy.

How do corporations effectively express to their stake-

holders the ethical principles of their organizations and (re-

)gain their trust? The current study examines the degree to

which ethics statements use various normative ethical

frameworks in reasoning and tone. Do these statements

speak to rules and legal compliance, similar to ‘‘We obey

the law’’ at Arkansas Children’s Hospital (2010)? Or do the

statements consider outcomes such as being ‘‘a special

company and an exceptional place to work’’ at Gilbane

(2010)? Or maybe the statements have an emotional appeal

to relationships and the human condition: ‘‘Growing pro-

fessionally, having fun with our colleagues, and finding

satisfaction in our work are central to our way of life’’ from

Kimley-Horn and Associates (2010)?

K. F. Hoover (&) ! M. B. Pepper

Gonzaga University, 502 East Boone Avenue, Spokane,

WA 99258, USA

e-mail: [email protected]

M. B. Pepper

e-mail: [email protected]

123

J Bus Ethics (2015) 131:605–617](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13leadershipethicsdescriptionthischapterisdifferentfrom-221224050948-cf742ea5/85/13-Leadership-EthicsDescriptionThis-chapter-is-different-from-docx-170-320.jpg)

![1REVITALIZING A UTILITARIAN BUSINESS ETHIC FOR

SOCIAL WELL-BEING

Let us . . . find ourselves, our places and our duties insociety,

and then, gathering courage from this newand broader

understanding of life in all its relations,

address ourselves seriously to the problem of making our-

selves and our neighbors useful, prosperous and happy.

Such is the supreme object of utilitarian economics.

Phelps and Myrick (1922, p. 7)

[T]he utilitarian standard is not the agent’s own greatest

happiness, but the greatest amount of happiness altogether;

and if it might possibly be doubted whether a noble character

is always the happier for its nobleness, there can be no

doubt that it makes other people happier, and that the world

is in general is immensely a gainer by it.

Mill (1998, ch. 2, para. 9, l. 4)

Utilitarianism provides a vision of ethical behavior which holds

the common interests of humanity as of utmost importance when

we make a moral decision. Utilitarianism fits business well if

we

conceive of business as a means of transforming culture and

society, and utilitarianism is the ethical perspective which most

easily helps us to address the ethical relationship and responsi-

bilities between business and society. Surely, nothing is more

powerful than business itself in shaping our cities, our work

environments, our playing environments, our values, desires,

hopes, and imagination. Business provides great goods for

society

through goods and services, jobs, tax revenue, and many

common](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13leadershipethicsdescriptionthischapterisdifferentfrom-221224050948-cf742ea5/85/13-Leadership-EthicsDescriptionThis-chapter-is-different-from-docx-225-320.jpg)

![that the classical utilitarianism of Mill is not equivalent to a

number of other theories referred to as utilitarianism—views

which business ethicists are right to criticize. First, as

mentioned,

it is not mere profit maximization, which is from some business

literature. Second, it is not preference utilitarianism—the view

that the source of both morality and ethics in general is based

upon subjective preference.2 (Rabinowicz and Österberg 1996).

Third, it is not a “rational actor” model. (McCracken and Shaw

1995) The rational actor model “utilitarianism” is well defined

by

McCracken and Shaw as holding that (1) humans are rational,

(2)

rational behavior is characterized by preference or value

maximi-

zation, (3) businesses seek to be profit maximizing, (4) the

moral

good is utility, (so therefore) (5) ethical business practice

consists

of maximizing profits within a framework of enlightened, but

not

clearly defined, rules, rights, and obligations.

328 BUSINESS AND SOCIETY REVIEW

This “rational actor model” is ethically problematic, and

McCracken and Shaw are right to point out that “[t]o analyze

business decisions using as a model an individual solely moti-

vated by the maximization of value or of profits, without regard

to

his or her own character, is totally unrealistic. It does not speak

to the role of ‘Nobility,’ ‘Sacrifice,’ ‘Sportsmanship,’

‘heroism,’ and

the like—” (McCracken and Shaw 1995, p. 301). Mill’s utilitari-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13leadershipethicsdescriptionthischapterisdifferentfrom-221224050948-cf742ea5/85/13-Leadership-EthicsDescriptionThis-chapter-is-different-from-docx-229-320.jpg)

![greatest happiness for the most.

Three key aspects of Mill’s utilitarianism distinguish his ethics

and so, a utilitarian business ethic: (1) it is consequentialist and

has a shared goal of the common good at its heart; (2) it takes

account of long-term consequences or the prosperity of society;

(3)

329ANDREW GUSTAFSON

it entails nurturing moral education in culture by developing

social concern in individuals.

First, Mill’s utilitarianism is a consequentialist ethical theory:

Mill’s utilitarianism is concerned about the welfare of the

many,

rather than just the individual, as he says, “[the utilitarian] stan-

dard is not the agents own greatest happiness, but the greatest

amount of happiness altogether” (Mill 1998, ch. 2, para. 9, l. 4).

It

is not mere egoism and, in fact, calls on an individual to

sacrifice

one’s own happiness on occasion, if it is for the greater

common

good. For Mill’s utilitarianism according to this “Greatest

Happiness

Principle”—“the ultimate end, with reference to and for the

sake of

which all other things are desirable . . . is an existence exempt

as

far as possible from pain, and as rich as possible in enjoyments,

both in point of quantity and quality” (Mill 1998, ch. 2, para.

10, l.

1). Greatest happiness might come by a wide distribution of](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13leadershipethicsdescriptionthischapterisdifferentfrom-221224050948-cf742ea5/85/13-Leadership-EthicsDescriptionThis-chapter-is-different-from-docx-231-320.jpg)

![hap-

piness to the most, or in some cases, the interests of the many

might be served actually by affording something to the minority

(such as providing fair trial to all, even those who are

apparently

guilty—which maintains a happier society than one which does

not

provide fair trials (Sadam’s Iraq, Syria, North Korea, etc).3

Utilitarianism fits business well, because business often thinks

in terms of utility. However, utilitarianism is not concerned

with

the interest of the individual only, or even of the larger distribu-

tive sum or aggregate of the happiness of individuals (Audi

2007).

Rather, Mill’s utilitarianism is concerned with the happiness of

humanity as a whole—his is a corporate narrative aimed at “cre-

ating bonds between the individual and humanity at large”

(Heydt

2006, p. 105). On this view, “[h]umanity begins to appear as a

‘corporate being’ rather than as a simple aggregate of

individuals,

when one begins to imagine it as having a destiny” (Heydt 2006,

p. 105).4 The difficulty is trying to help people to start to think

of

social utility, not just personal or profit-maximization utility,

and

to realize that we must consider long-term social utility, not just

social utility for this evening. This involves having a vision of

the

good of humanity in mind when making decisions. In the words

of

Mill, the utilitarian conceives of life this way:

So long as they are co-operating, their ends are identified

with those of others; there is at least a temporary feeling that](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13leadershipethicsdescriptionthischapterisdifferentfrom-221224050948-cf742ea5/85/13-Leadership-EthicsDescriptionThis-chapter-is-different-from-docx-232-320.jpg)

![the interests of others are their own interests. Not only does

330 BUSINESS AND SOCIETY REVIEW

all strengthening of social ties, and all healthy growth of

society, give to each individual a stronger personal interest in

practically consulting the welfare of others; it also leads him

to identify his feelings more and more with their good, or at

least with an ever greater degree of practical consideration

for it. He comes, as though instinctively, to be conscious of

himself as a being who of course pays regard to others. The

good of others becomes to him a thing naturally and neces-

sarily to be attended to, like any of the physical conditions of

our existence. (Mill 1998, ch. 3, para. 1, l. 30)

Such utilitarianism will not answer every single dilemma, but it

does give direction in many situations. Mill believes humans

have

a fellow feeling toward other human beings, and that this

feeling

can be nurtured and trained as one develops a vision of oneself

as

a member of this society of humanity and as we integrate indi-

viduals into a strong culture of concern for others (more of this

on

the succeeding paragraphs).

Second, Mill’s utilitarianism pursues long-term benefit and so

has

rules of morality following from the Greatest Happiness

Principle

(GHP) which provide moral guidance.5 Mill says, “Whatever we

adopt

as the fundamental principle of morality [the GHP], we require](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13leadershipethicsdescriptionthischapterisdifferentfrom-221224050948-cf742ea5/85/13-Leadership-EthicsDescriptionThis-chapter-is-different-from-docx-233-320.jpg)

![on this specific occasion the benefit will come.10

Third, moral education toward a culture of ethical–social

concern is essential (Gustafson 2009; Heydt 2006). Mill’s

utilitari-

anism relies on education and the development of social ties to

undergird our moral motivation so that we will act according to

the GHP. This is the sort of corporate culture construction

which

we achieve through strategized ethical training and integrity

development, not unlike the model Sharpe-Paine calls the

integrity

approach (in contrast to the compliance approach) (Paine 1994).

Throughout his Utilitarianism and On Liberty, we find Mill

arguing

that without proper socialization and moral education, people

will

not be enabled to pursue the GHP because they will be oblivious

to it and incapable of desiring it. But fortunately, because

humans have fellow feelings, these can be nurtured and trained

toward a strong culture of social concern:

[T]he smallest germs of the feeling are laid hold of an nour-

ished by the contagion of sympathy and the influences of

education; and a complete web of corroborative associations

is woven round it, by the powerful agency of the external

sanctions. This mode of conceiving ourselves and human life,

as civilization goes on, is felt to be more and more natural.

(Mill 1998, ch. 3, para. 1, l. 44)

The first means of encouraging utilitarianism is not legal, but

cultural: “that education and opinion, which have so vast a

power

over human character, should so use that power as to establish

in

the mind of every individual an indissoluble association](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13leadershipethicsdescriptionthischapterisdifferentfrom-221224050948-cf742ea5/85/13-Leadership-EthicsDescriptionThis-chapter-is-different-from-docx-237-320.jpg)

![ciples such as justice and truth telling, which would make

the keeping of contracts a matter of convenience at best.

2. The Supererogatory Objection: utilitarianism leads to irratio-

nal and futile conclusions which are unworkable and unten-

able in the business place because it asks too much of us.

3. The Majority-bias Objection. utilitarianism is biased against

the minority viewpoint and so is unnecessarily blind both

to the dignity of individuals and to innovation from dissenters.

4. The Motivation Objection: utilitarianism fails to provide

moral

motivation for this social concern it requires.

5. The Calculation Objection: utilitarianism is considered

fatally

flawed insofar as it cannot provide an adequate calculus

system to do the utilitarian calculus, leaving it impotent to

assist in making ethical business decisions.

Here, I aim to show that one can, on the basis of Mill’s utilitari-

anism, respond to these criticisms and that a robust and fruitful

utilitarian theory can be quite able to help us develop a vision

of

business ethics.

Convenience: Utilitarianism Has No Principles: Justice and

Rights Go out the Window

It is often said that utilitarianism cannot adequately provide an

explanation for rights, duties, or justice because it will compro-

mise these for expedient good of the greater happiness for the

majority: “Perhaps the strongest criticism that can be made

against a utilitarian approach is that it completely and totally

ignores rights [of individuals]” (McGee 2008). Utilitarians are

cari-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13leadershipethicsdescriptionthischapterisdifferentfrom-221224050948-cf742ea5/85/13-Leadership-EthicsDescriptionThis-chapter-is-different-from-docx-240-320.jpg)

![catured at being willing to do anything, so long as the majority

benefits. For example, it has been said that Oliver North’s

decep-

tive lying about the Iran-Contra affair of the 1980’s was a clear

example of utilitarian reasoning:

North’s method of justifying his acts of deception is a form of

moral reasoning that is called ‘utilitarianism.’ Stripped down

335ANDREW GUSTAFSON

to its essentials, utilitarianism is a moral principle that holds

that the morally right course of action in any situation is the

one that produces the greatest balance of benefits over

harms for everyone affected. So long as a course of action

produces maximum benefits for everyone, utilitarianism does

not care whether the benefits are produced by lies, manipu-

lation, or coercion. (Velasquez et al. 1989)

Here, utilitarianism is characterized as justifying acts of

deception

through lies, manipulation, or coercion. If one considers happi-

ness of the majority above all else, it is said, then a utilitarian

will

give up justice for expediency and will ignore principles and

rights

when it is beneficial to the majority. Hartman likewise claims

that

“[t]he determination always to perform whatever act, or even

whatever sort of act, maximizes happiness will have unhappy

consequences, not least as a result of the breakdown of rules

and

institutions that enable people to trust one another” (Hartman

1996, p. 46). This criticism actually makes the point for](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13leadershipethicsdescriptionthischapterisdifferentfrom-221224050948-cf742ea5/85/13-Leadership-EthicsDescriptionThis-chapter-is-different-from-docx-241-320.jpg)

![utilitari-

anism! On Mill’s utilitarianism, if in fact an act would have

unhappy consequences—including “the breakdown of rules and

institutions that enable people to trust each other”—then a utili-

tarian should not do that act. Lying and ignoring rights and

otherwise undermining basic stabilizing foundations of society

which make it a happy one are not in line with utilitarianism,

but

quite rejected by a utilitarian ethic.

However, there is still an apparently difficult dilemma for the

utilitarian here: either Mill remains committed to the principle

of

utility when possible exceptions arise, in which case he

acknowl-

edges that sometimes one morally ought to violate such alleged

rights as liberty and freedom, or else the utilitarian remains

com-

mitted to these rights even when they violate the principle of

utility. Mill addresses such concerns when he says, “We are told

that an utilitarian will be apt to make his own particular case an

exception to moral rules, and, when under temptation, will see

an

utility in the breach of a rule, greater than he will see in its

observance” (Mill 1998, ch. 2, para. 25, l. 4). His response is,

first,

to admit that utilitarianism can be misused as a rationalizing

excuse for doing evil—but all moral creeds can be misused.

Second, he points out that there are often “conflicting

situations”

and that “[t]here is no ethical creed which does not temper the

336 BUSINESS AND SOCIETY REVIEW](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13leadershipethicsdescriptionthischapterisdifferentfrom-221224050948-cf742ea5/85/13-Leadership-EthicsDescriptionThis-chapter-is-different-from-docx-242-320.jpg)

![25, l. 1). In some cases, such as when a criminal, politician, or

other person whose security is in danger is protected from angry

protesters, society has police risk their lives for the security of

a

citizen. So, the reasons for protecting the rights of an individual

or

minority group are (1) a society which maintains rights of indi-

vidual or minority will be happier than a society which does not

provide such rights and (2) the pain to the individual or

minority

group outweighs the cost to the majority more often than not (if

the individual does not get fair trial they get lynched. The

majority

pays for this with time/patience and some tax dollars, which,

distributed across the public, are a small cost per person).

So, with respect to Bowie’s point, Mill’s actually agrees that

you

should not ask that the humanity of one set of stakeholders be

sacrificed for the humanity of another group solely on the

grounds that there are more stakeholders in one group than

another (Audi 2007). That would be to ignore the amount of

happiness and quality of the happiness involved. Promoting

indi-

vidual liberties does contribute to the overall happiness capacity

(“utility”) of society at large.

But again and again, we find it claimed that utilitarianism itself

is totalitarian and homogenous, tending to undermine individual

liberty and creativity:

[I]t is a good thing that utilitarianism cannot get off the

ground. It is a good thing that we, and most particularly our

political and economic institutions, respect a variety of con-

ceptions of the good and a variety of kinds of life, rather than

imposing a single one on all within the community. We rightly](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13leadershipethicsdescriptionthischapterisdifferentfrom-221224050948-cf742ea5/85/13-Leadership-EthicsDescriptionThis-chapter-is-different-from-docx-253-320.jpg)

![grant people autonomy in that sense. (Hartman 1996, p. 61)

While some utilitarian models may quash variety and diversity,

Mill clearly supports the principle of liberty and wants it

because

343ANDREW GUSTAFSON

he thinks a free society is a better pleasure-producing society

(Gustafson 2009). Mill does think that providing protection for

minority behaviors and activities does in fact directly contribute

to

the greater good of society. Mill would support diversity,

affirma-

tive action, and proactive support of women in traditionally

male

workplaces, and males in traditionally female workplaces. He

sees

diversity in general as a great happiness-producing asset to

society. He brings this out most clearly in his On Liberty where

he

provides explicitly utilitarian arguments for supporting the

liberty

of individual dissent against the majority—because it is in the

majority’s best interest to do so. Mill says that “the only

unfailing

and permanent source of improvement is liberty, because by it

there are as many possible independent centres of improvement

as

there are individuals” (Mill 1999, p. 117). For Mill, liberty is

what

provides opportunity for progress in society [or corporate

culture],

and homogeneity is much more dangerous, so individual liberty](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/13leadershipethicsdescriptionthischapterisdifferentfrom-221224050948-cf742ea5/85/13-Leadership-EthicsDescriptionThis-chapter-is-different-from-docx-254-320.jpg)