This document provides an overview of the topics that will be covered in a discrete mathematics course for computer science. It includes:

- Administrative details like the instructor's contact information, textbook, exam dates, and policies on cheating and late homework.

- The course objectives which are to learn basic discrete mathematics tools and techniques like propositional logic, set theory, counting, and induction, as well as rigorous mathematical reasoning and proof writing.

- Advice for students on how to study effectively and keep up in the course by practicing problems and examples.

- An outline of the topics to be covered, beginning with propositional logic - including truth tables, logical connectives, tautologies, and translating sentences -

![12

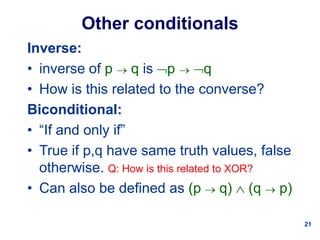

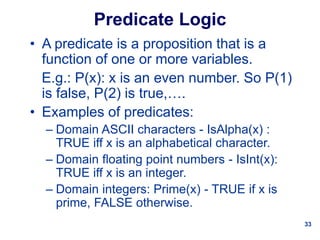

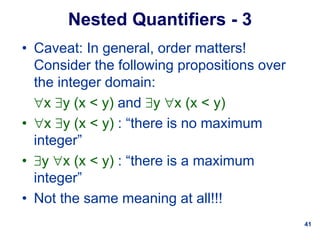

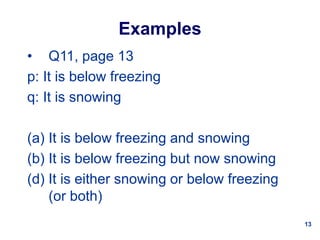

Conjunction, Disjunction

• Conjunction: p q [“and”]

• Disjunction: p q [“or”]

p q p q p q

T T T T

T F F T

F T F T

F F F F](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1019lec1-221231071722-abddc845/85/1019Lec1-ppt-12-320.jpg)

![15

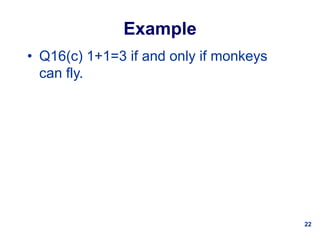

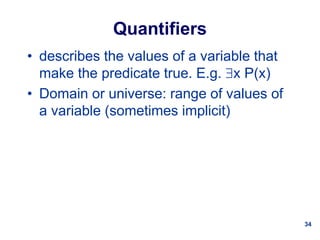

Conditional

• p q [“if p then q”]

• p: hypothesis, q: conclusion

• E.g.: “If you turn in a homework late, it will not

be graded”; “If you get 100% in this course,

you will get an A+”.

• TRICKY: Is p q TRUE if p is FALSE?

YES!!

• Think of “If you get 100% in this course, you

will get an A+” as a promise – is the promise

violated if someone gets 50% and does not

receive an A+?](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1019lec1-221231071722-abddc845/85/1019Lec1-ppt-15-320.jpg)

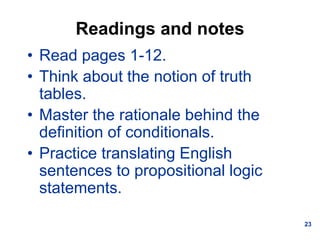

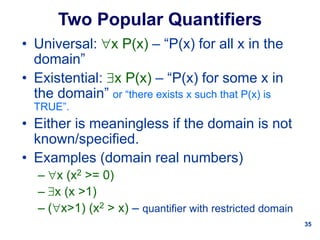

![16

Conditional - 2

• p q [“if p then q”]

• Truth table:

p q p q p q

T T T T

T F F F

F T T T

F F T T

Note the truth table of p q](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/1019lec1-221231071722-abddc845/85/1019Lec1-ppt-16-320.jpg)