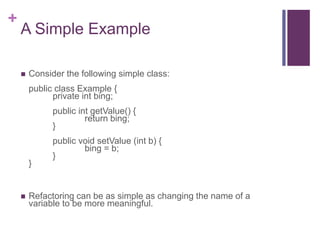

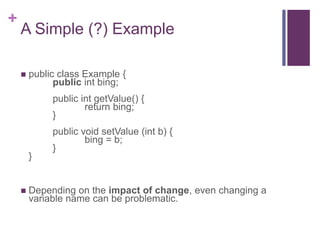

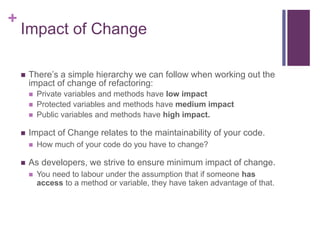

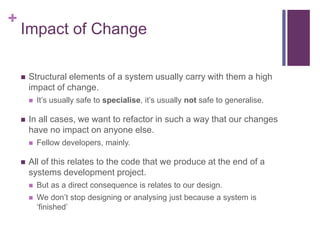

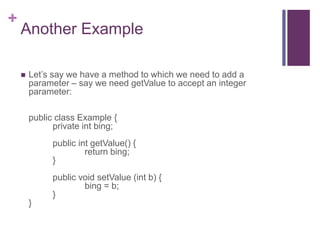

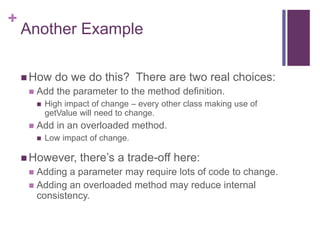

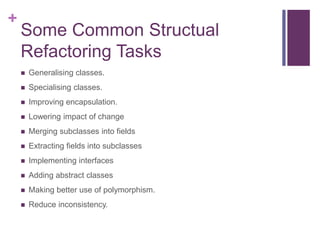

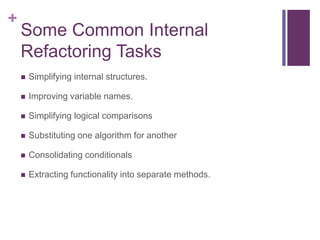

The document discusses refactoring as a process of improving code quality without changing external behavior. It is not about adding features or fixing bugs, but improving code structure and design to make it easier to maintain and change. Refactoring aims to improve code readability, efficiency, and flexibility by techniques like simplifying conditionals, extracting methods, and reducing dependencies between code elements. The impact of changes must be minimized by refactoring private elements before public ones. Tests are crucial to ensure refactoring does not introduce errors. Code is refactored when it shows signs of deterioration like duplication, overcomplexity, or tight coupling between modules.