The document outlines various data types in programming, including primitive types like integers, floating-point numbers, booleans, and characters, as well as structured types such as strings, enumerated types, arrays, and records. It explains the characteristics and operations associated with each type, detailing how they are implemented in different programming languages. Additionally, the document discusses pointers as a means of dynamically managing data structures and their operations.

![CSI 3125, Data Types, page 15

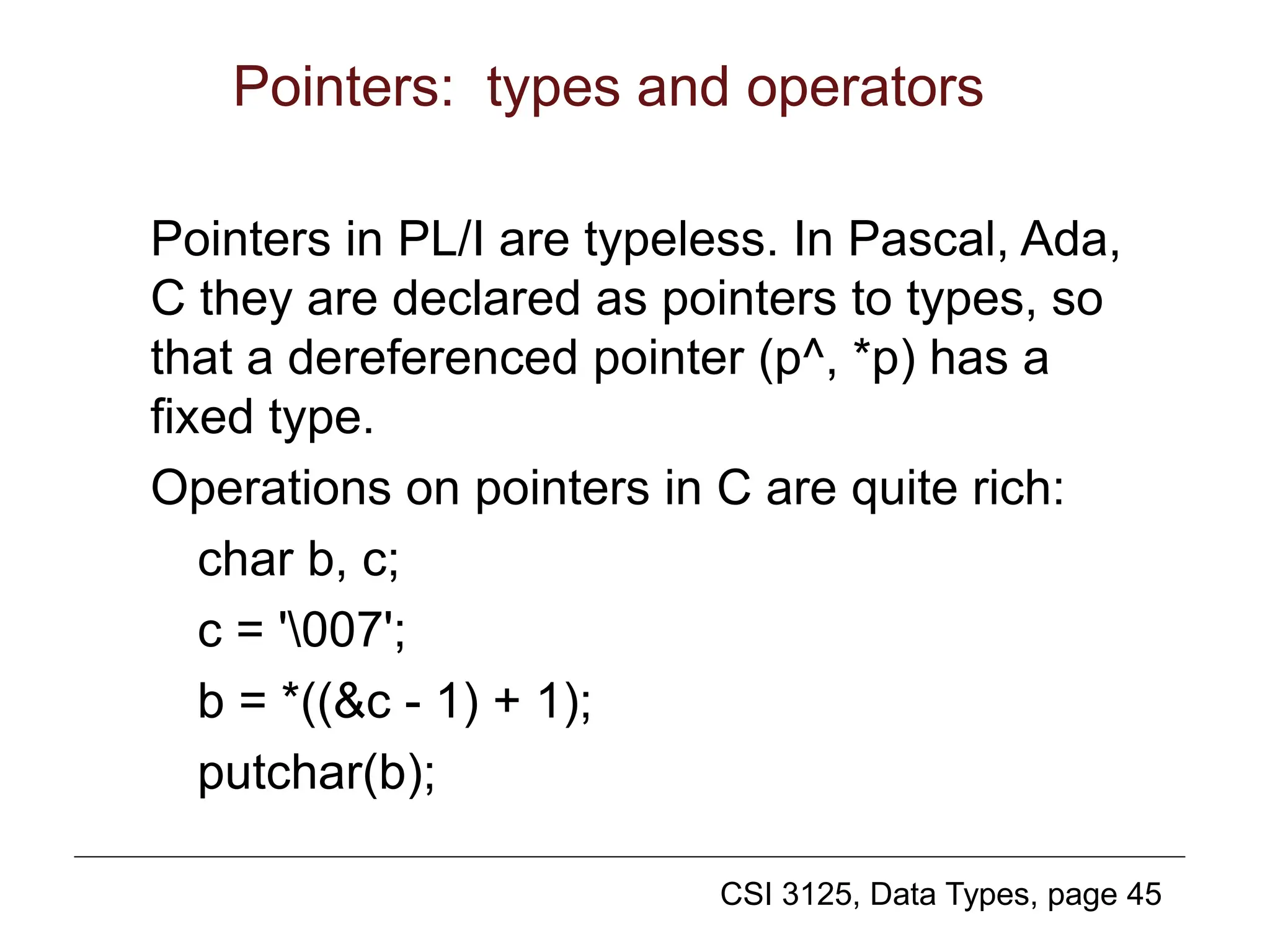

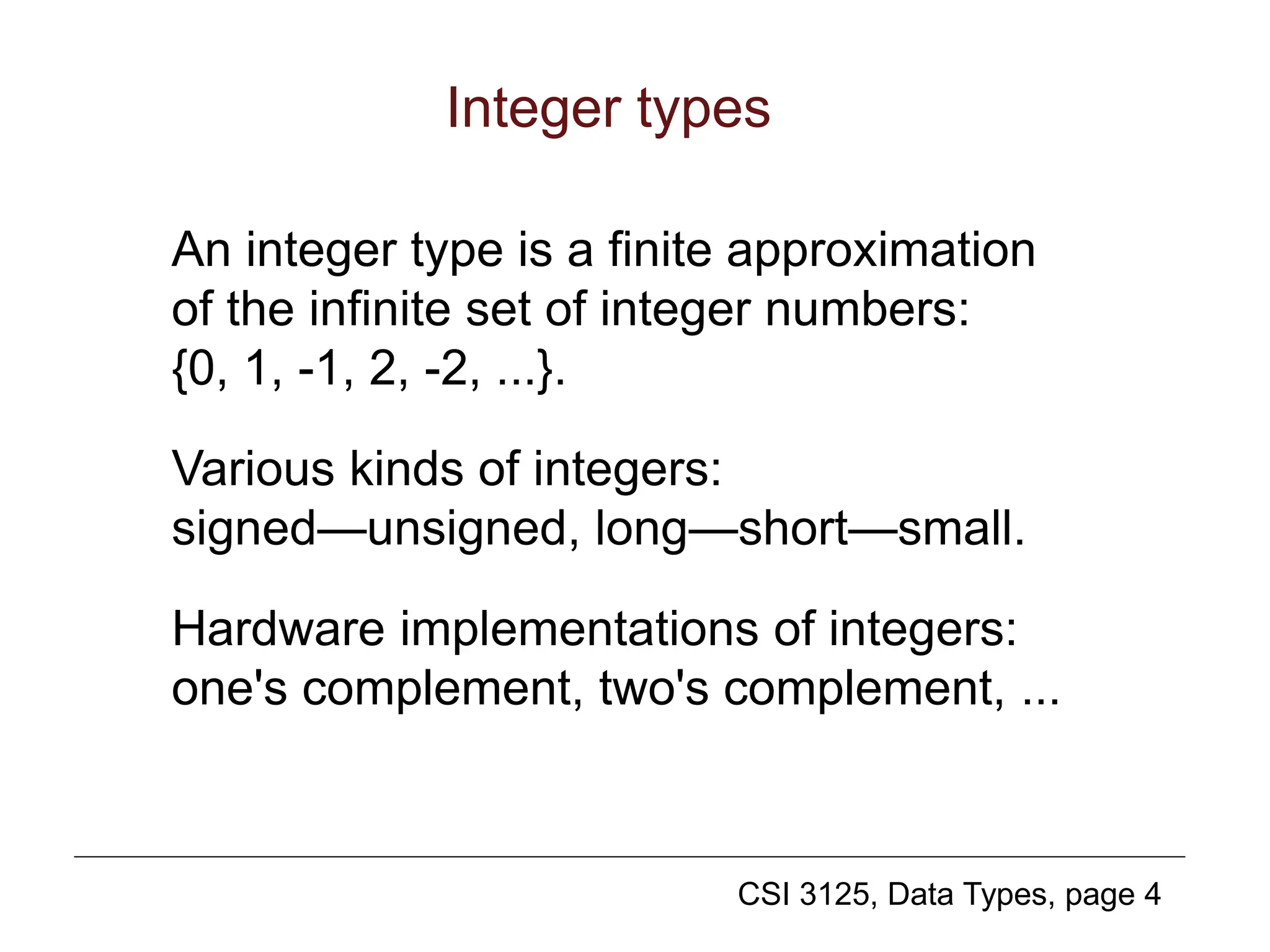

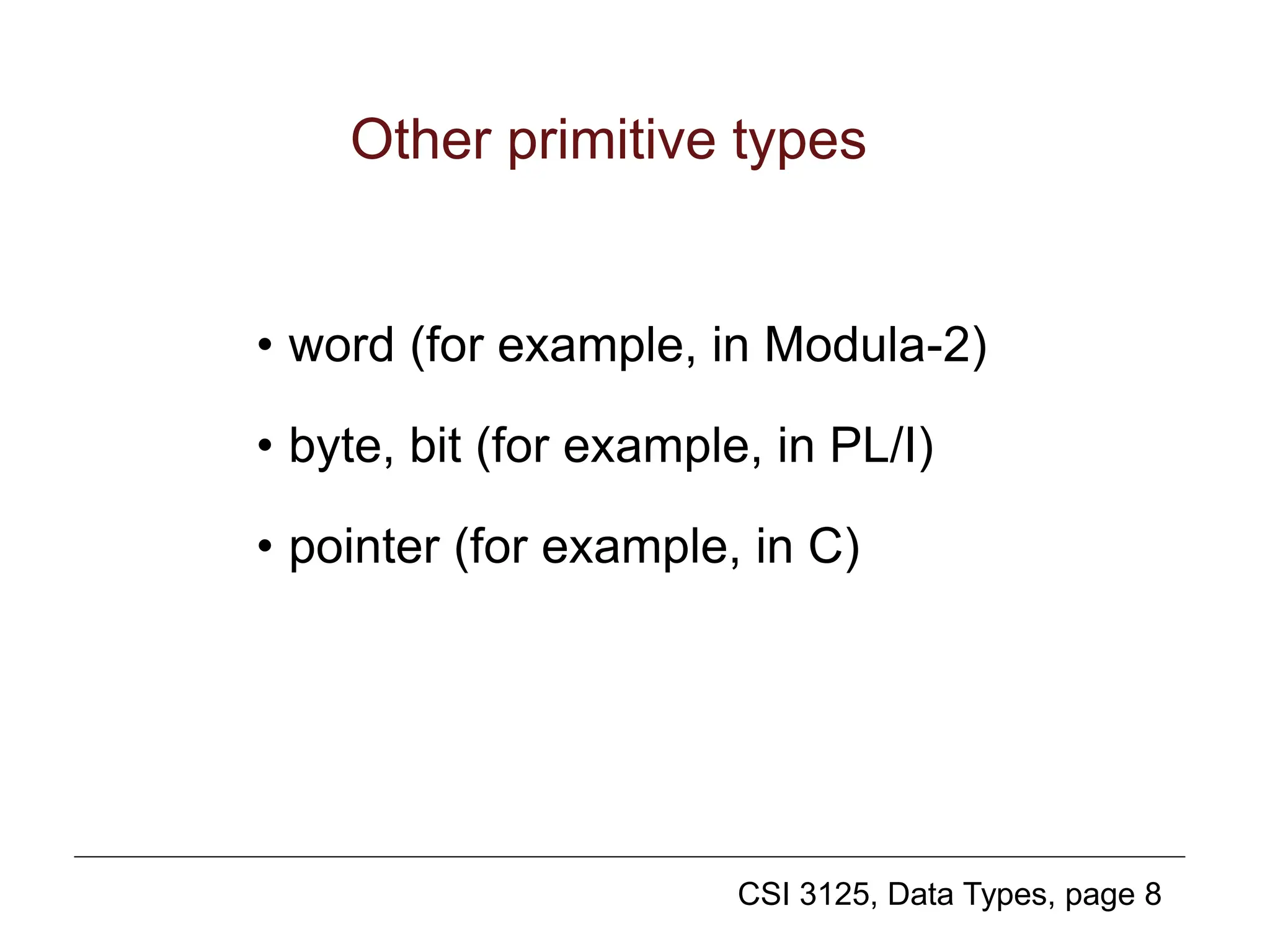

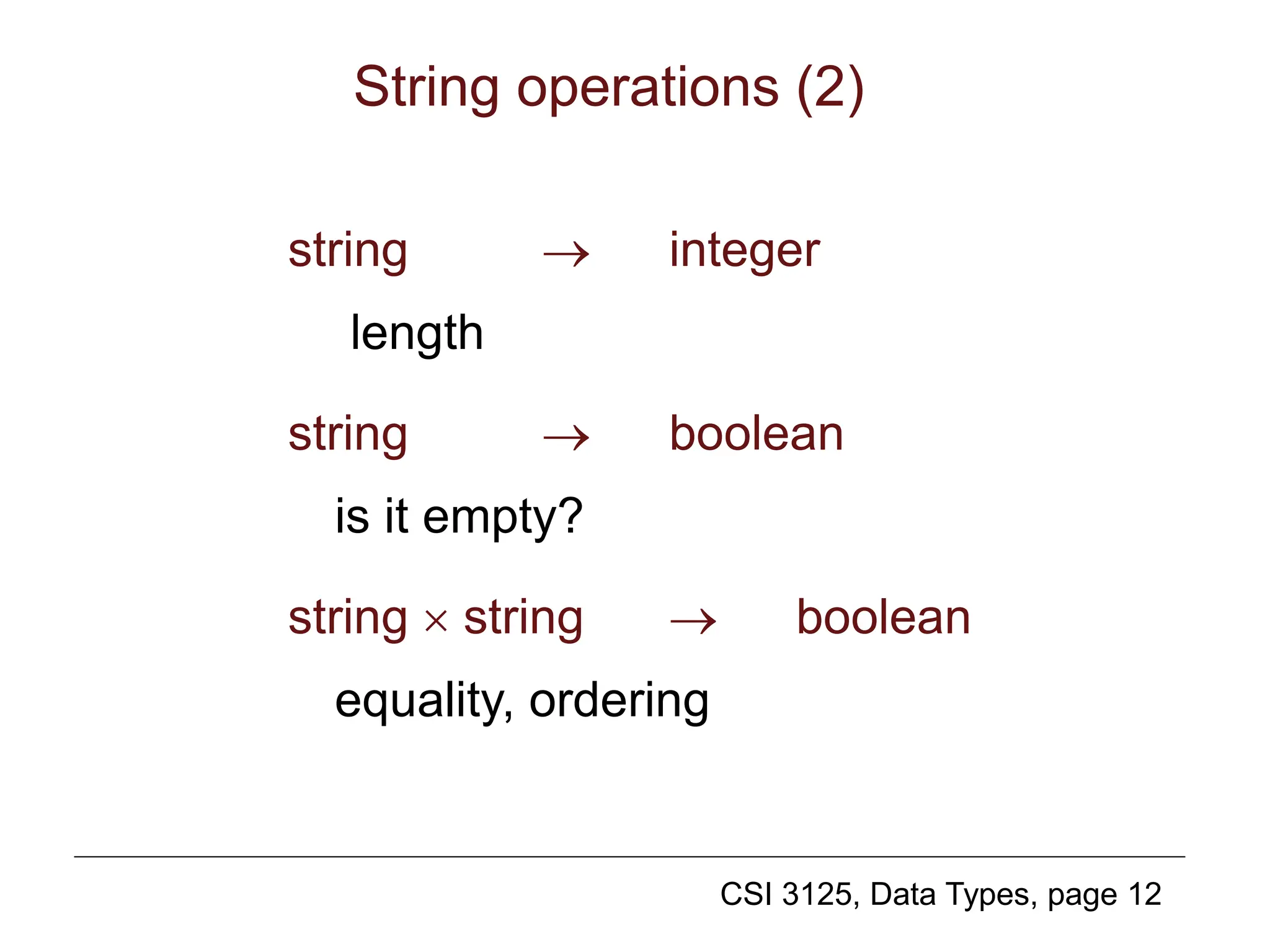

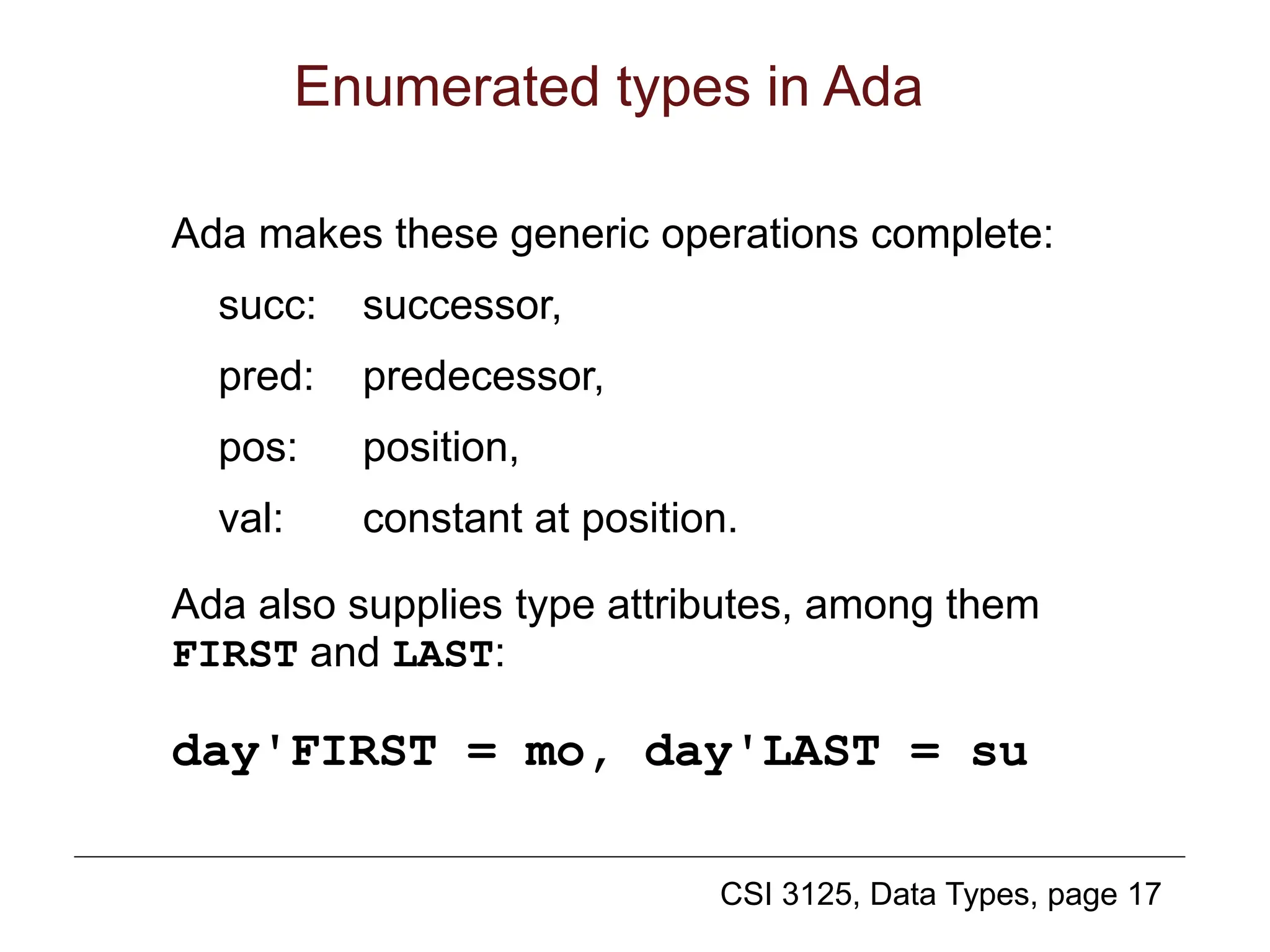

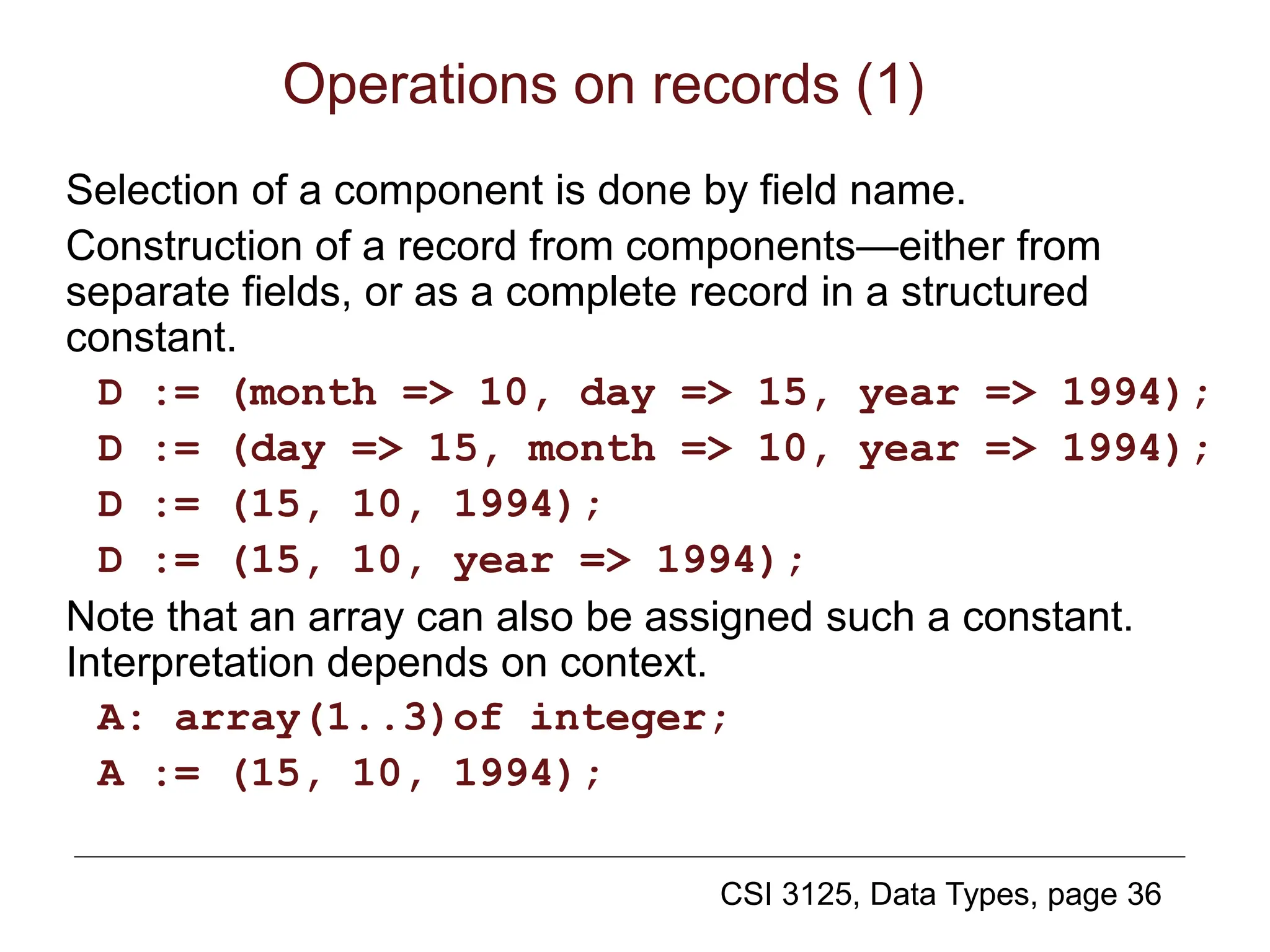

Enumerated types

Also called: user-defined ordinal types

[read Section 6.4]

We can declare a list of symbolic constants that are

to be treated literally, just like in Prolog or Scheme.

We also specify the implicit ordering of those newly

introduced symbolic constants. In Pascal:

type day =

(mo, tu, we, th, fr, sa, su);

Here, we have mo < tu < we < th < fr < sa < su.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/09datatypes-240420100358-35269b6b/75/09_java_DataTypesand-associated-class-ppt-15-2048.jpg)

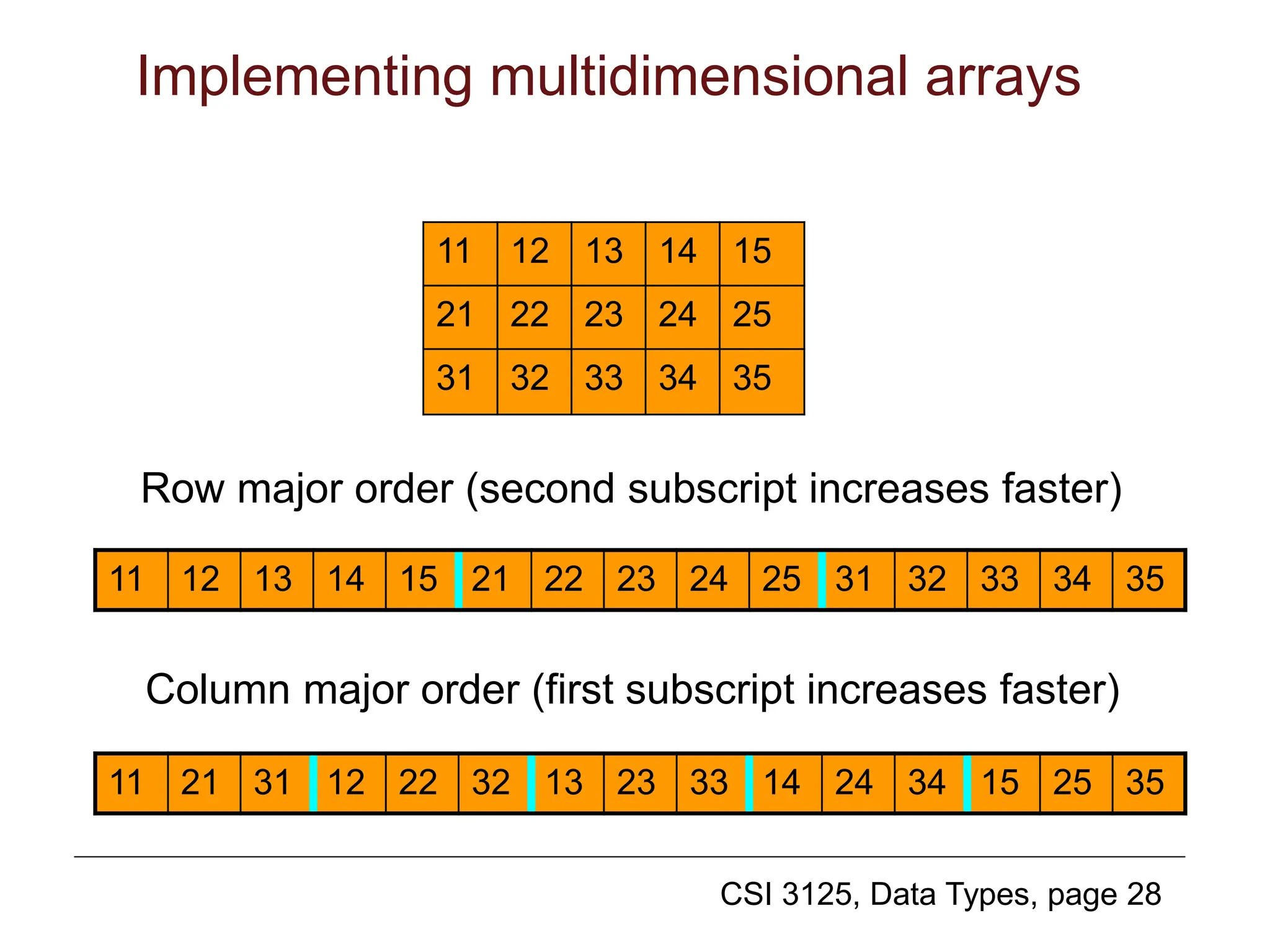

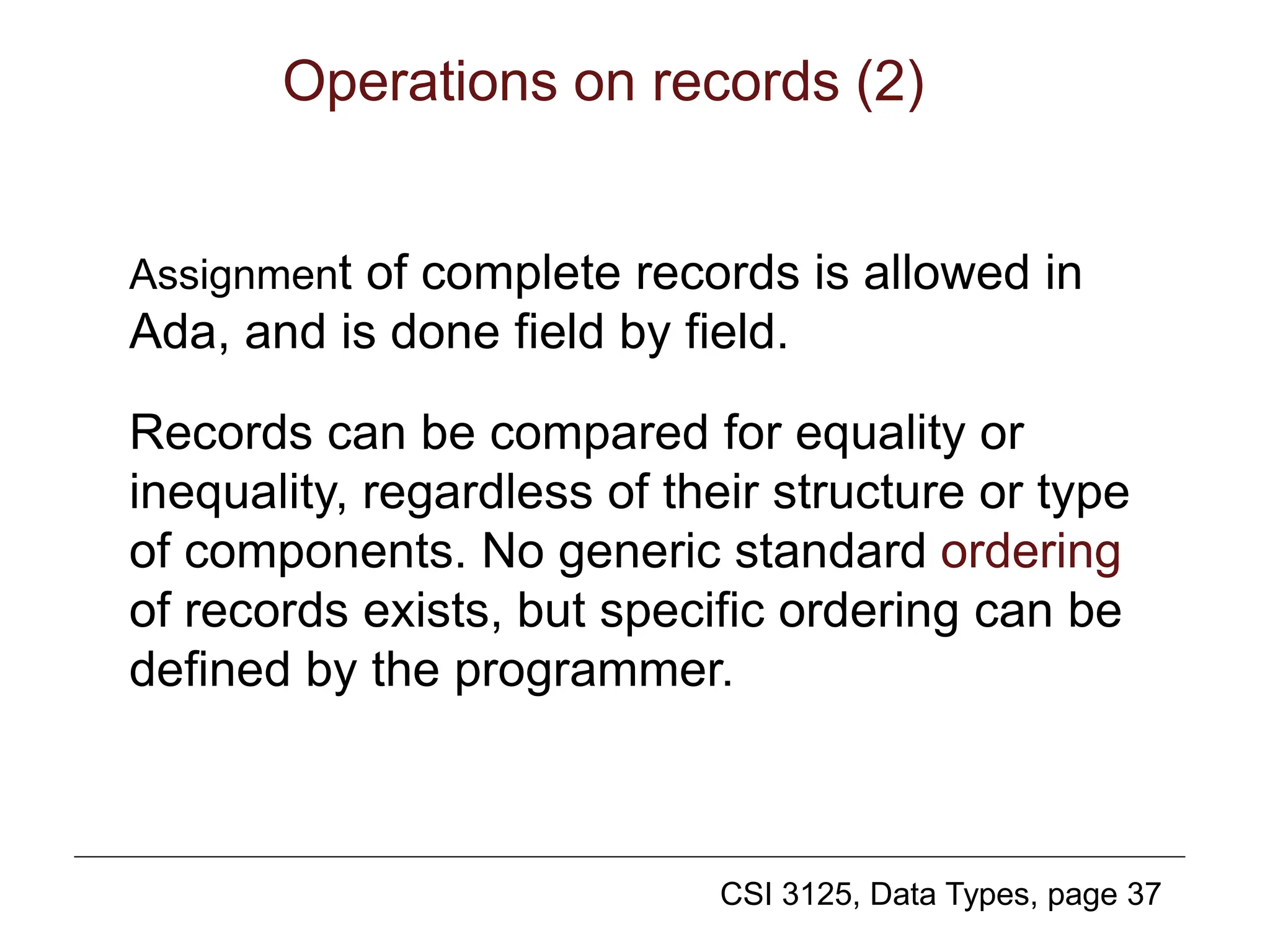

![CSI 3125, Data Types, page 21

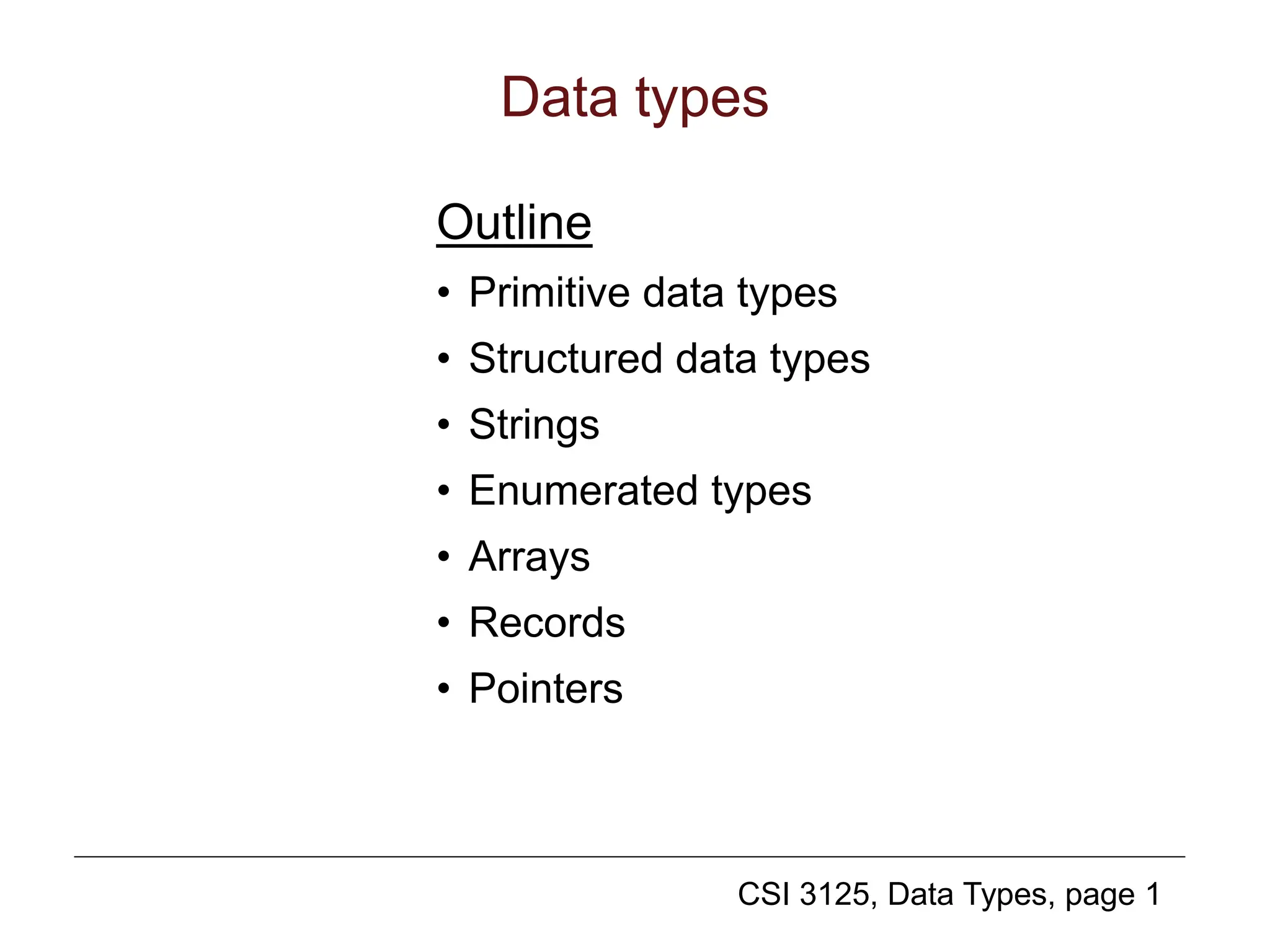

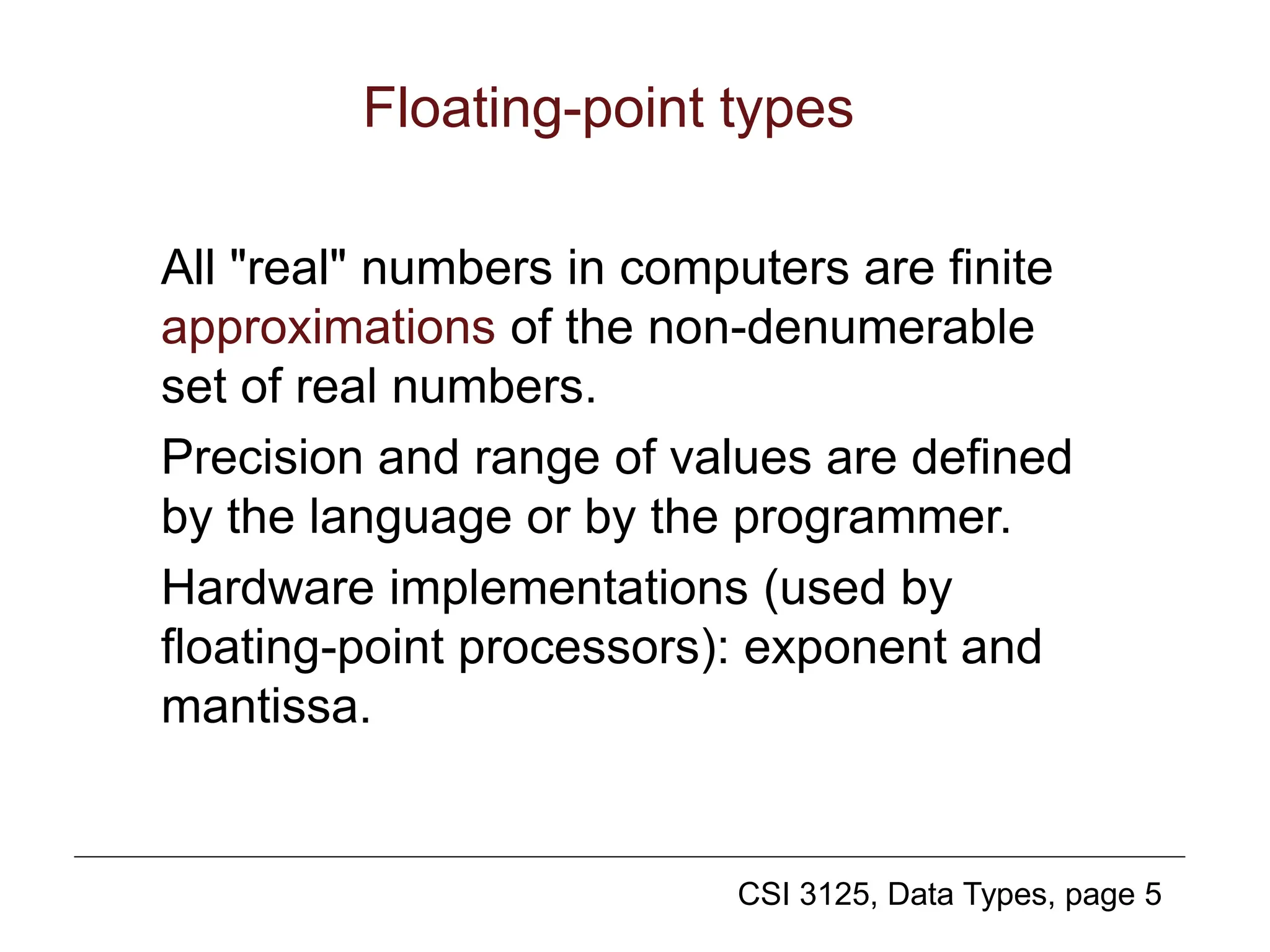

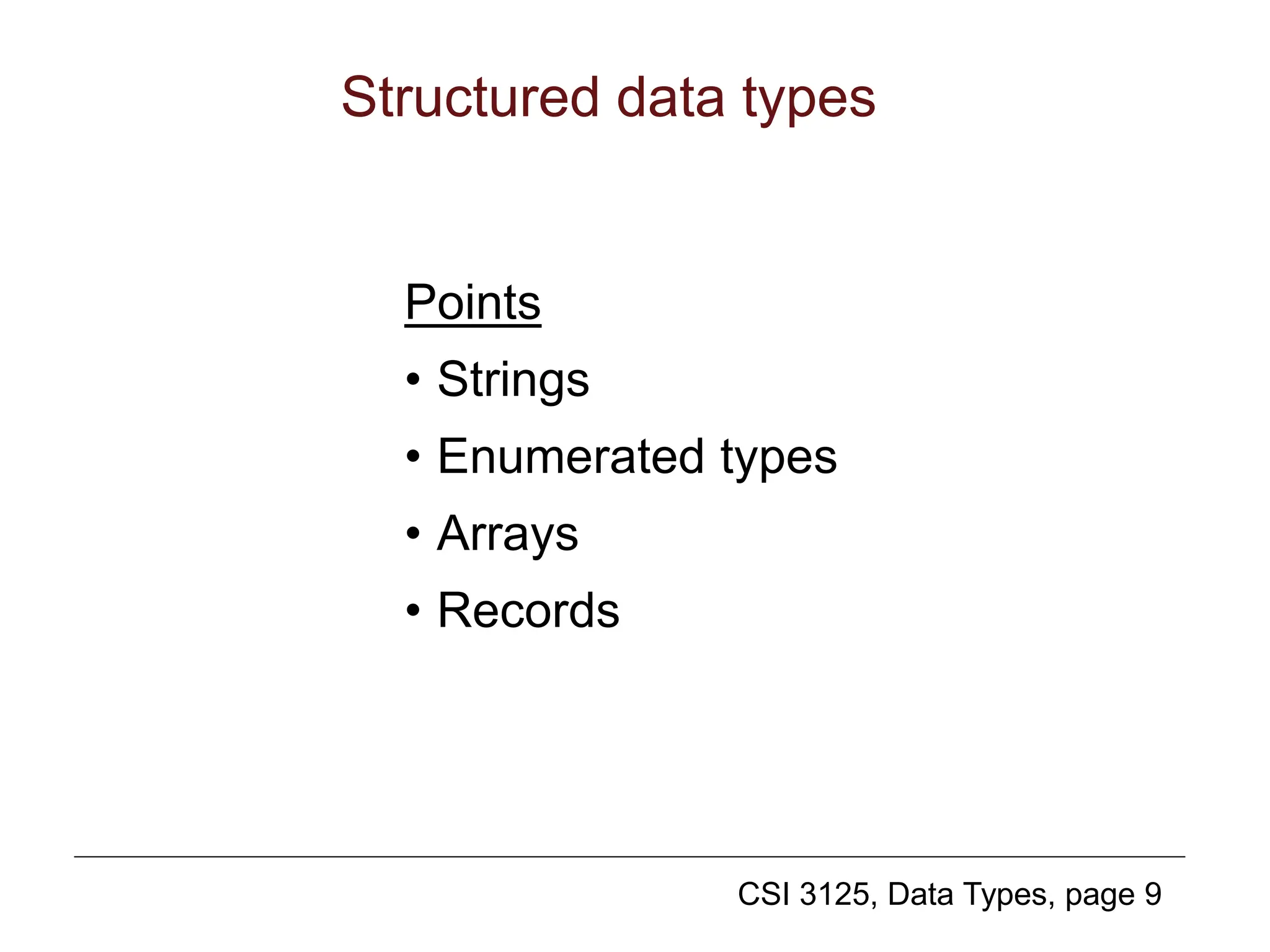

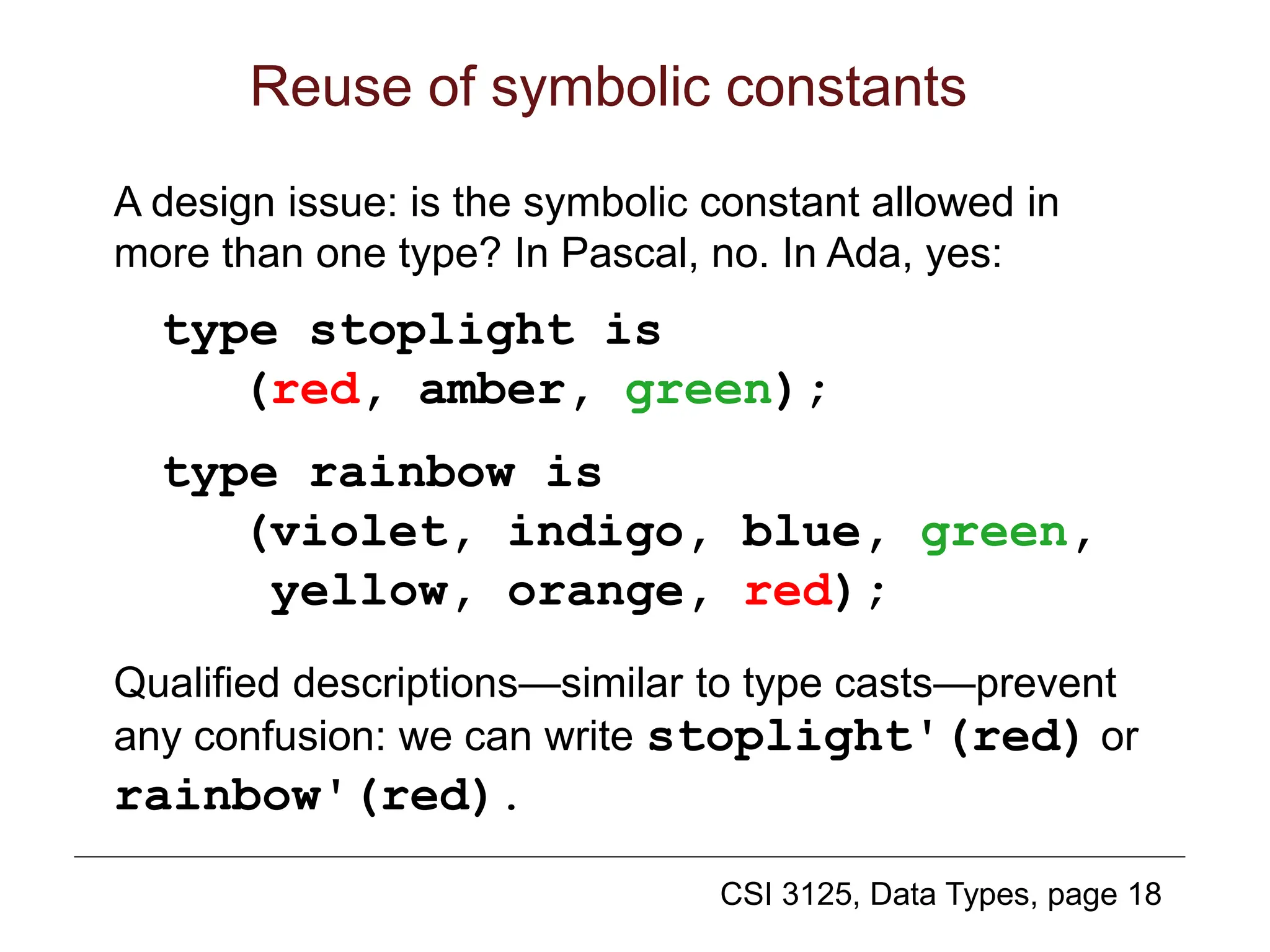

Multidimensional arrays

Multidimensional arrays can be defined in two

ways (for simplicity, we show only dimension 2):

index_type1 index_type2 component_type

This corresponds to references such as A[I,J].

Algol, Pascal, Ada work like this.

index_type1 (index_type2 component_type)

This corresponds to references such as A[I][J].

Java works like this.

Perl sticks to one dimension](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/09datatypes-240420100358-35269b6b/75/09_java_DataTypesand-associated-class-ppt-21-2048.jpg)

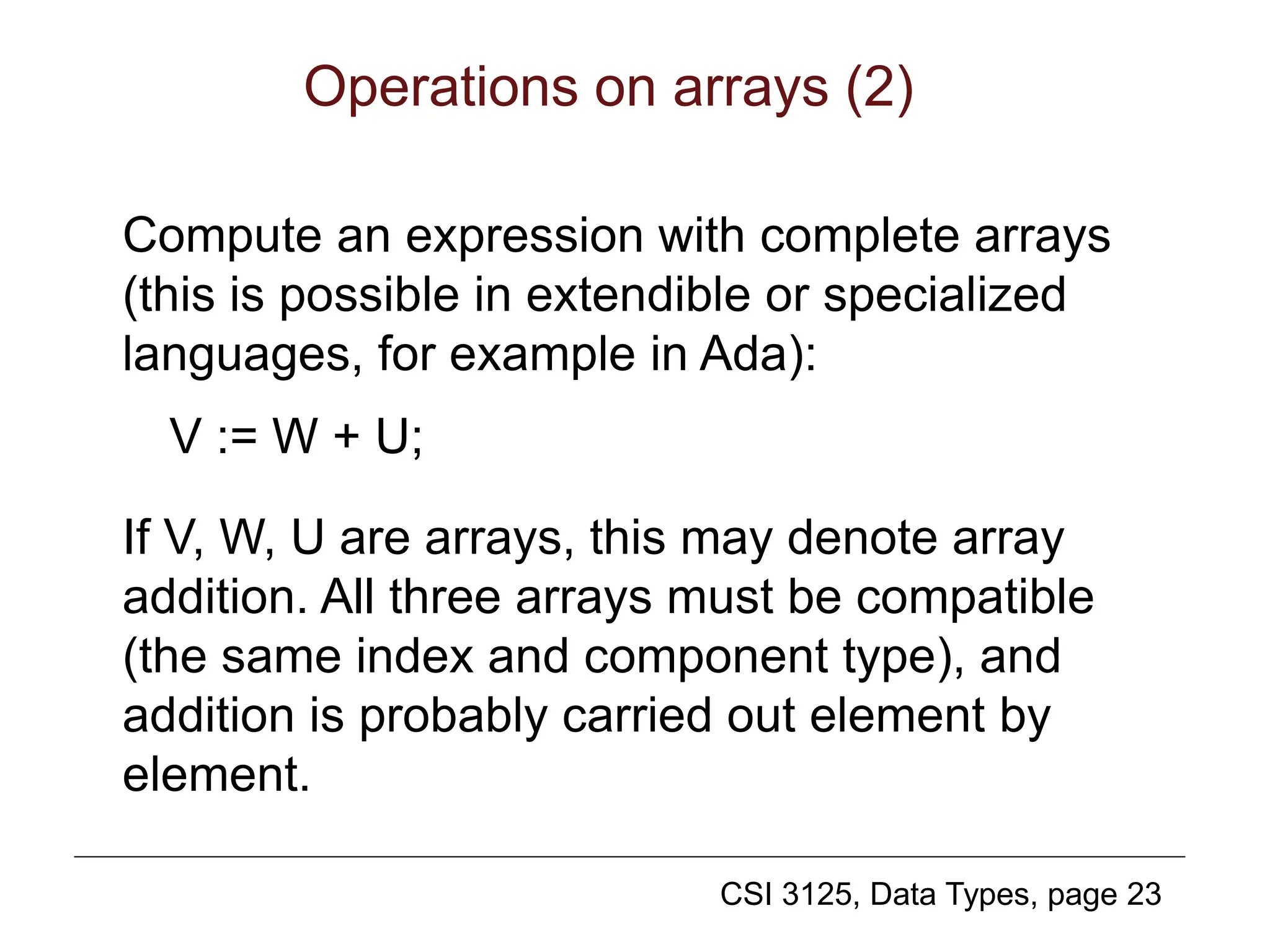

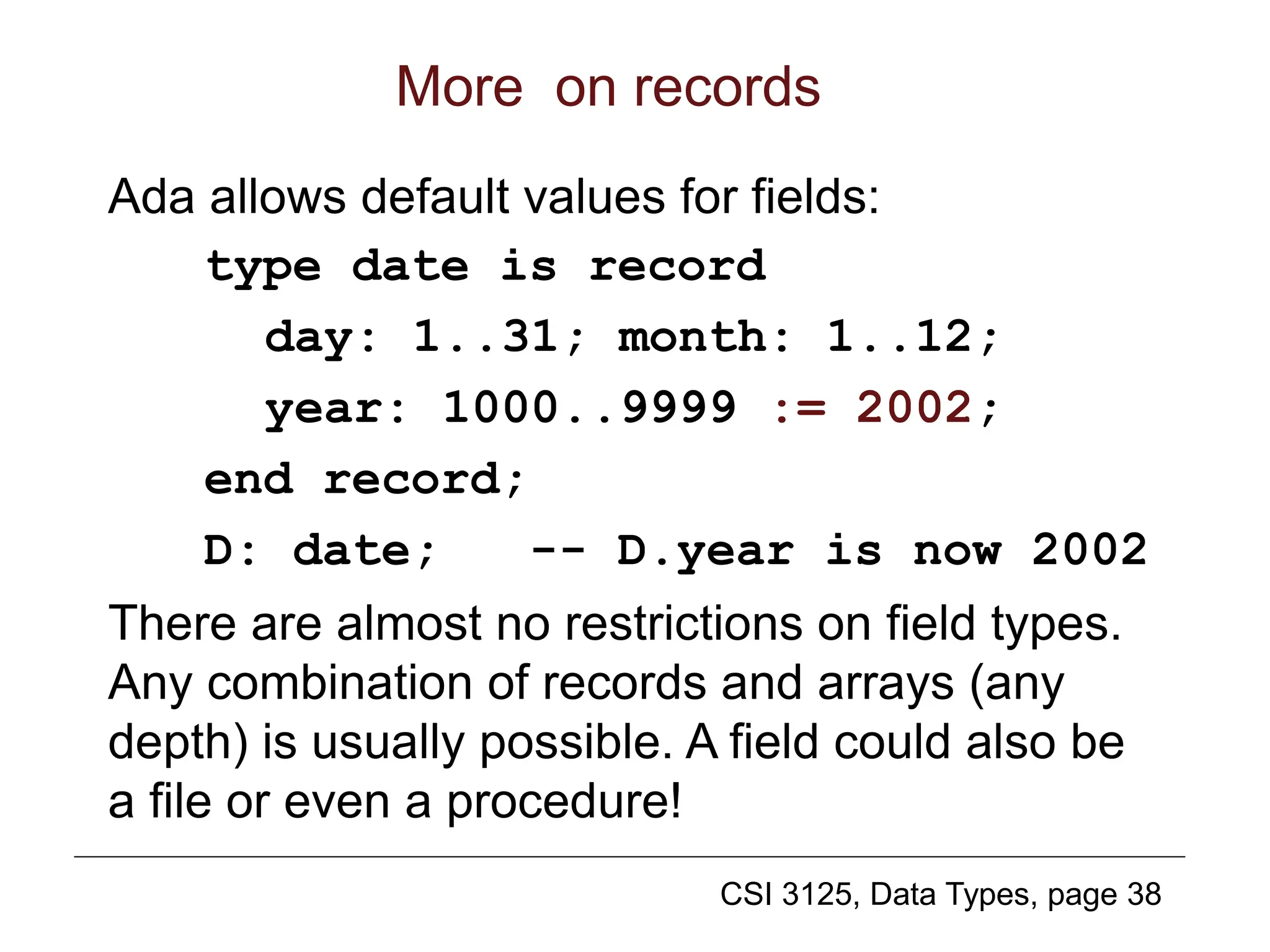

![CSI 3125, Data Types, page 22

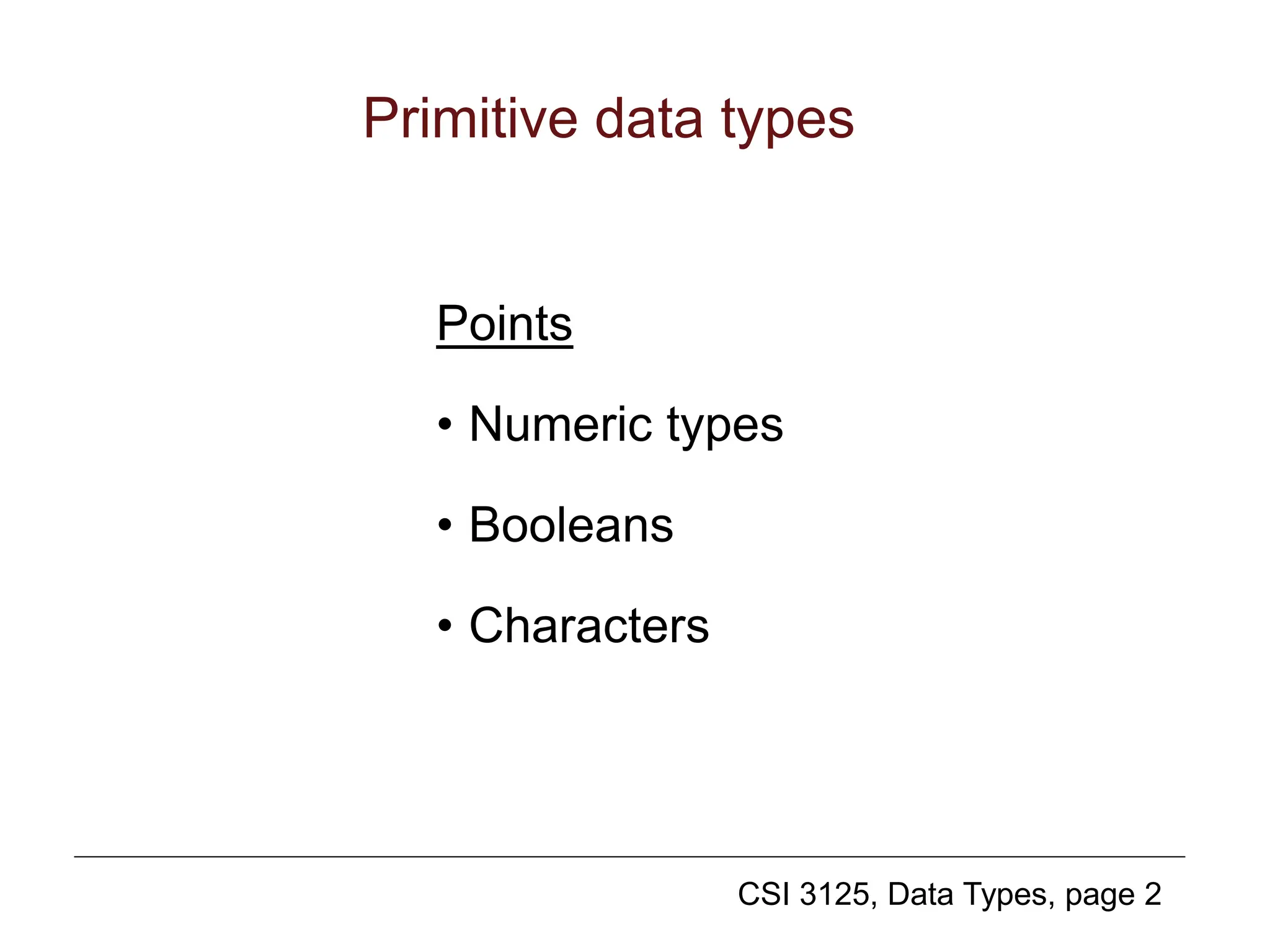

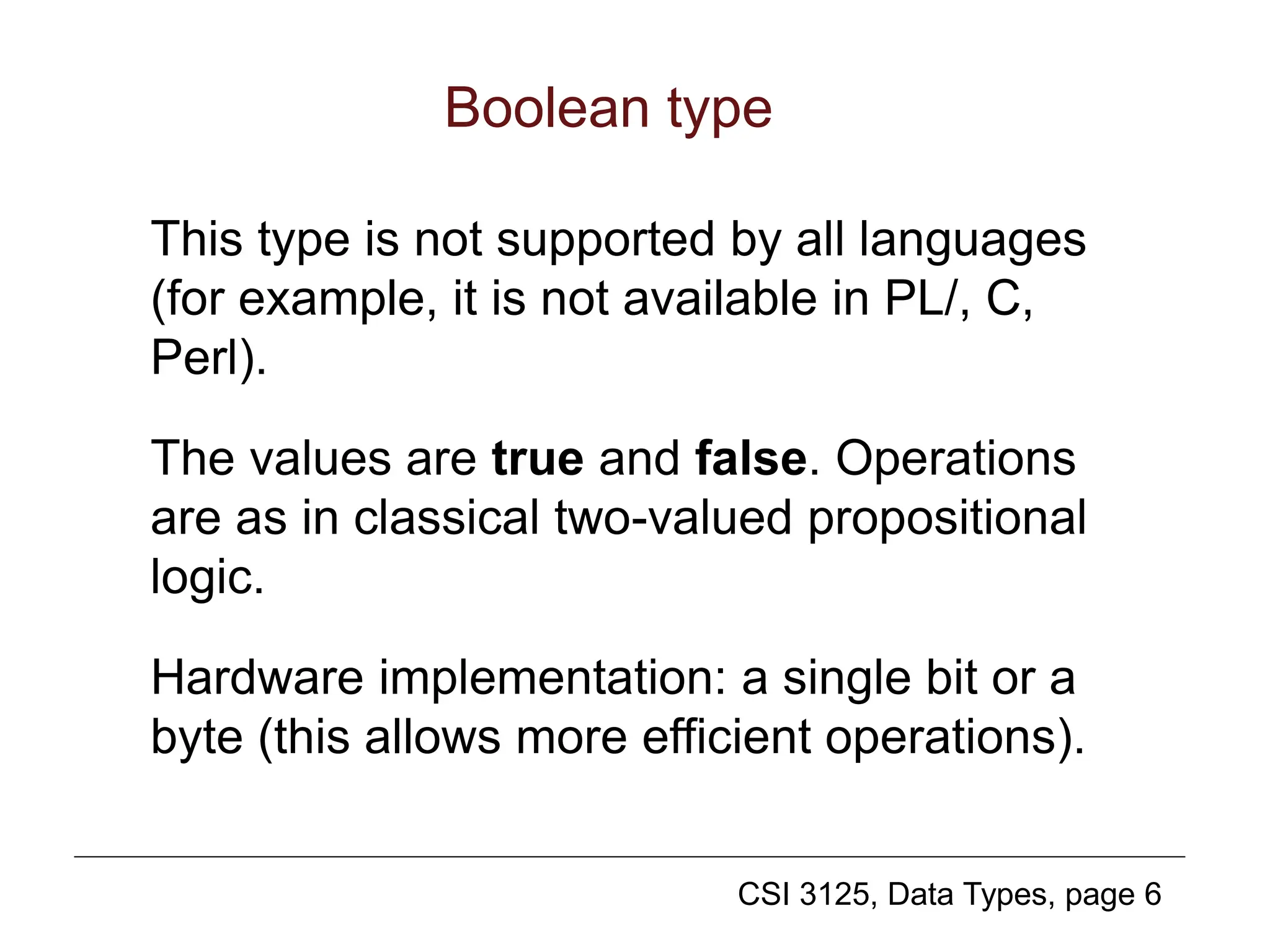

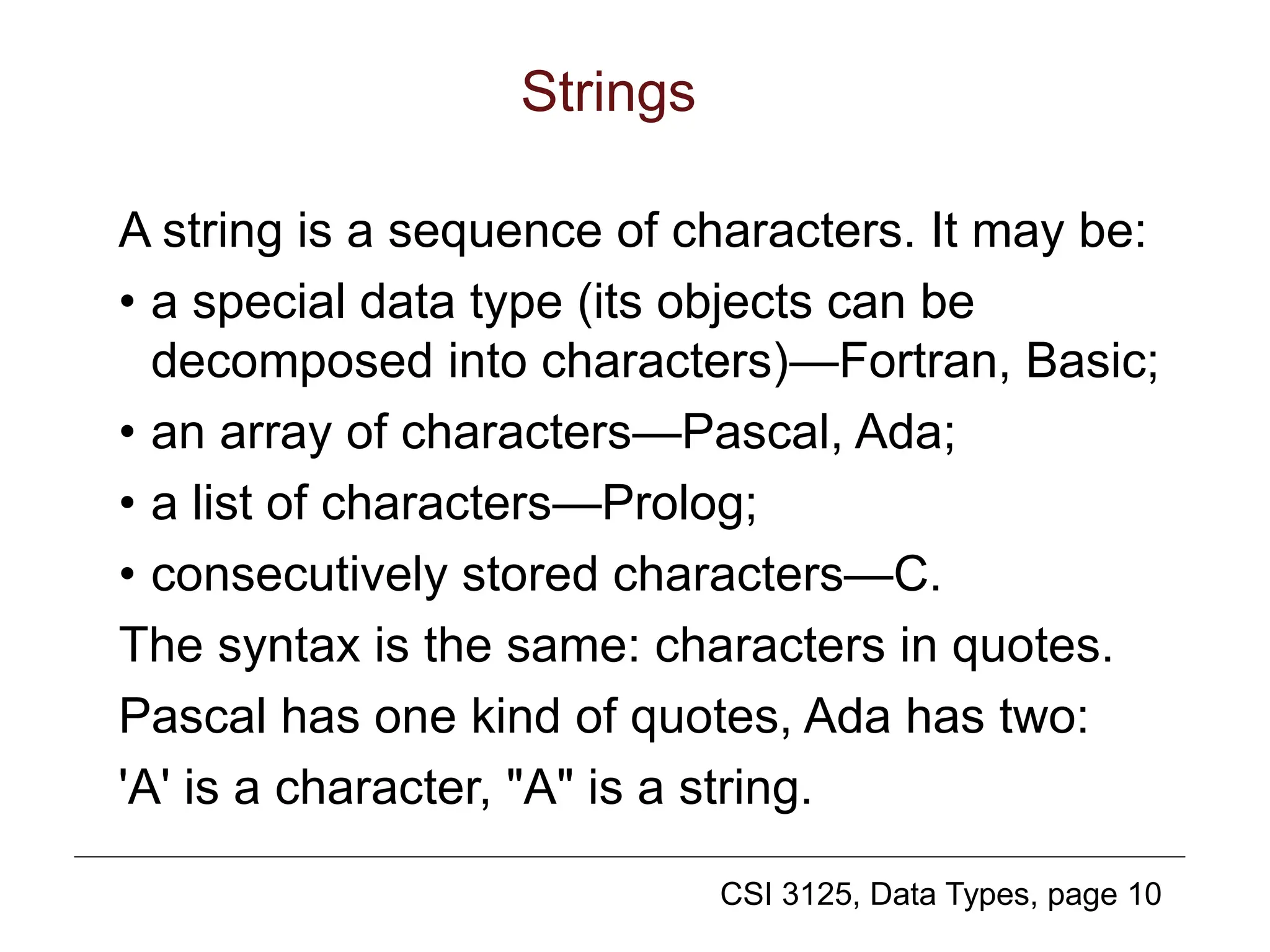

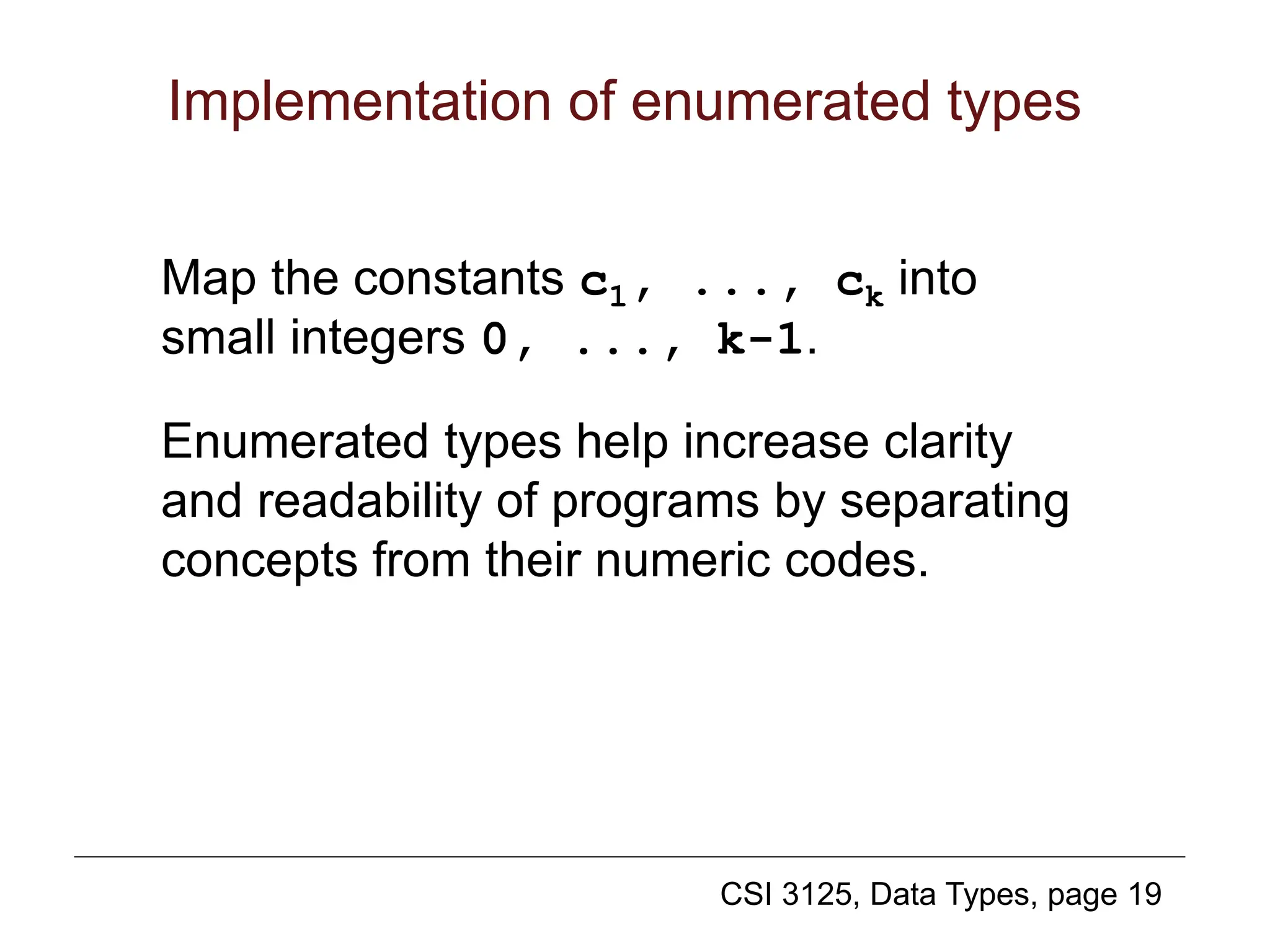

Operations on arrays (1)

select an element (get or change its value):

A[J]

select a slice of an array:

(read the textbook, Section 6.5.7)

assign a complete array to a complete array:

A := B;

There is an implicit loop here.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/09datatypes-240420100358-35269b6b/75/09_java_DataTypesand-associated-class-ppt-22-2048.jpg)

![CSI 3125, Data Types, page 25

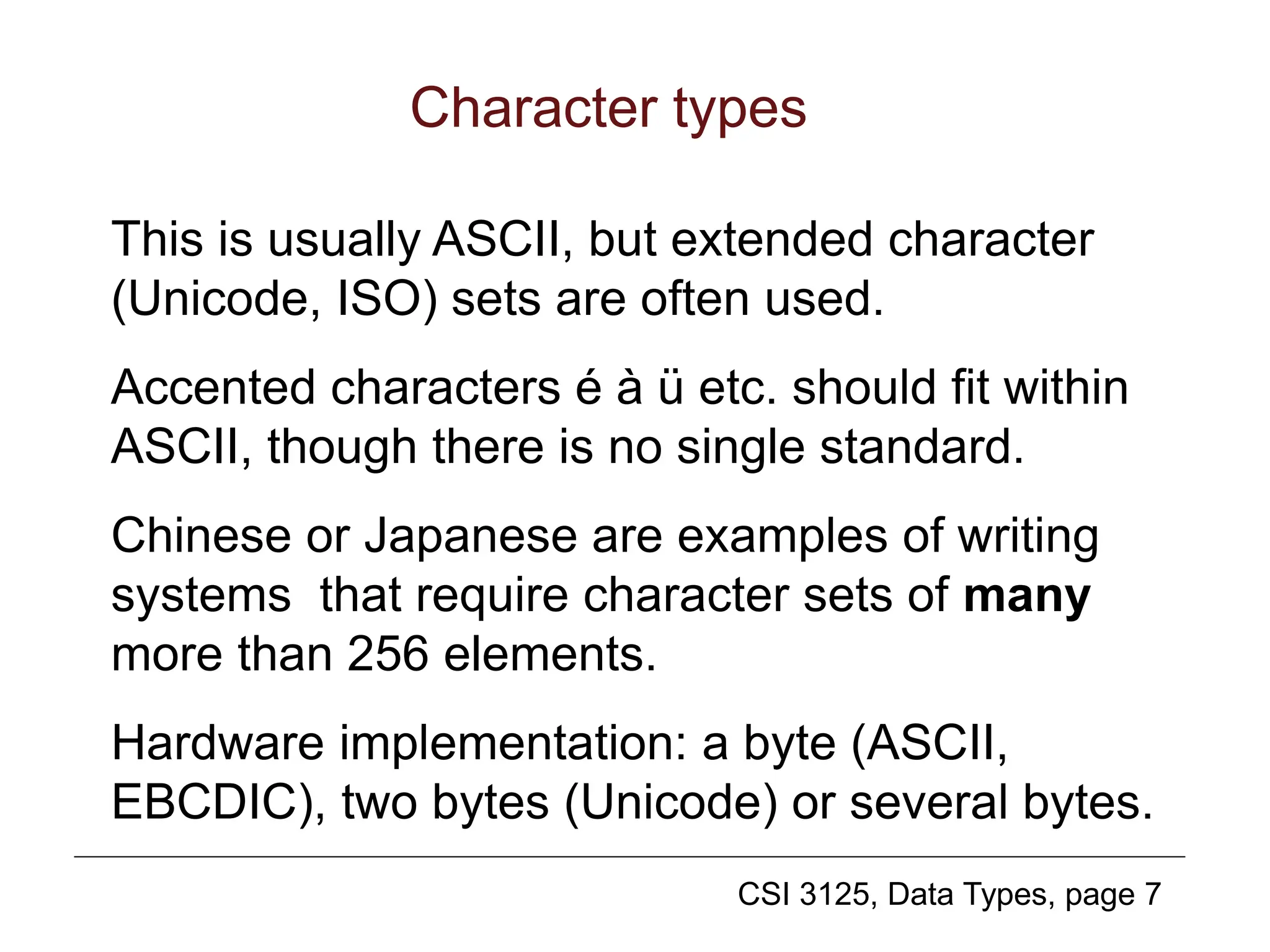

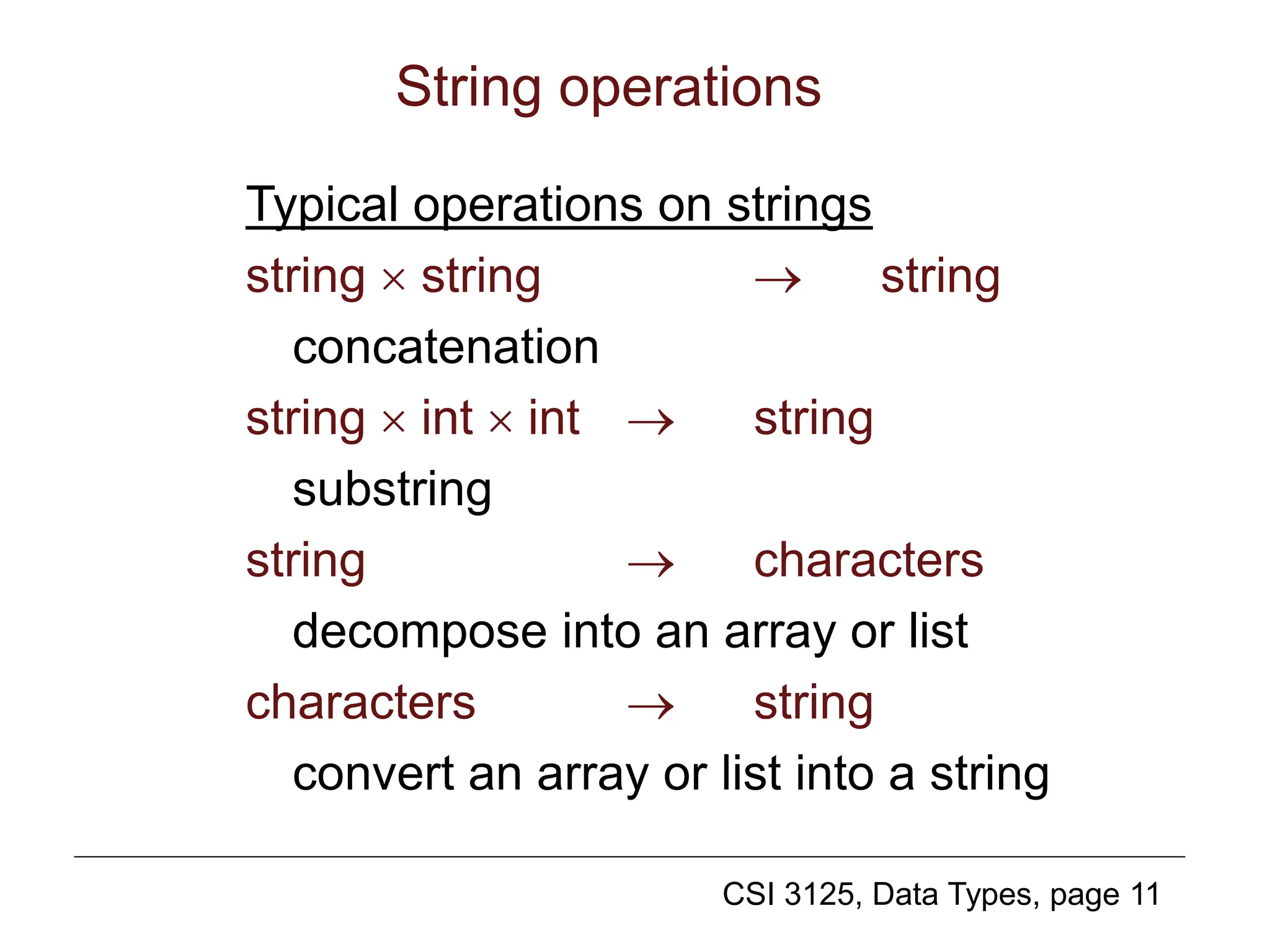

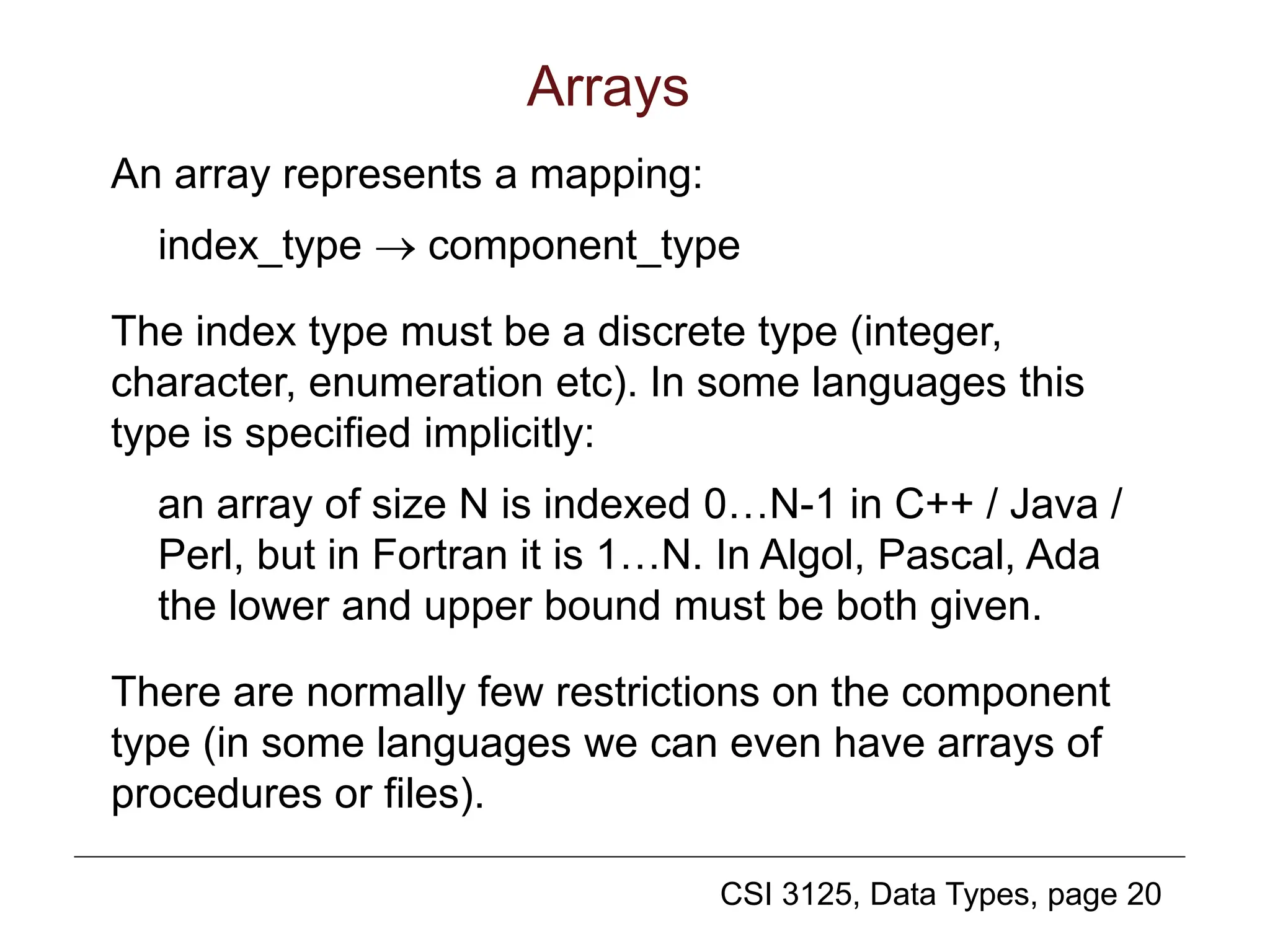

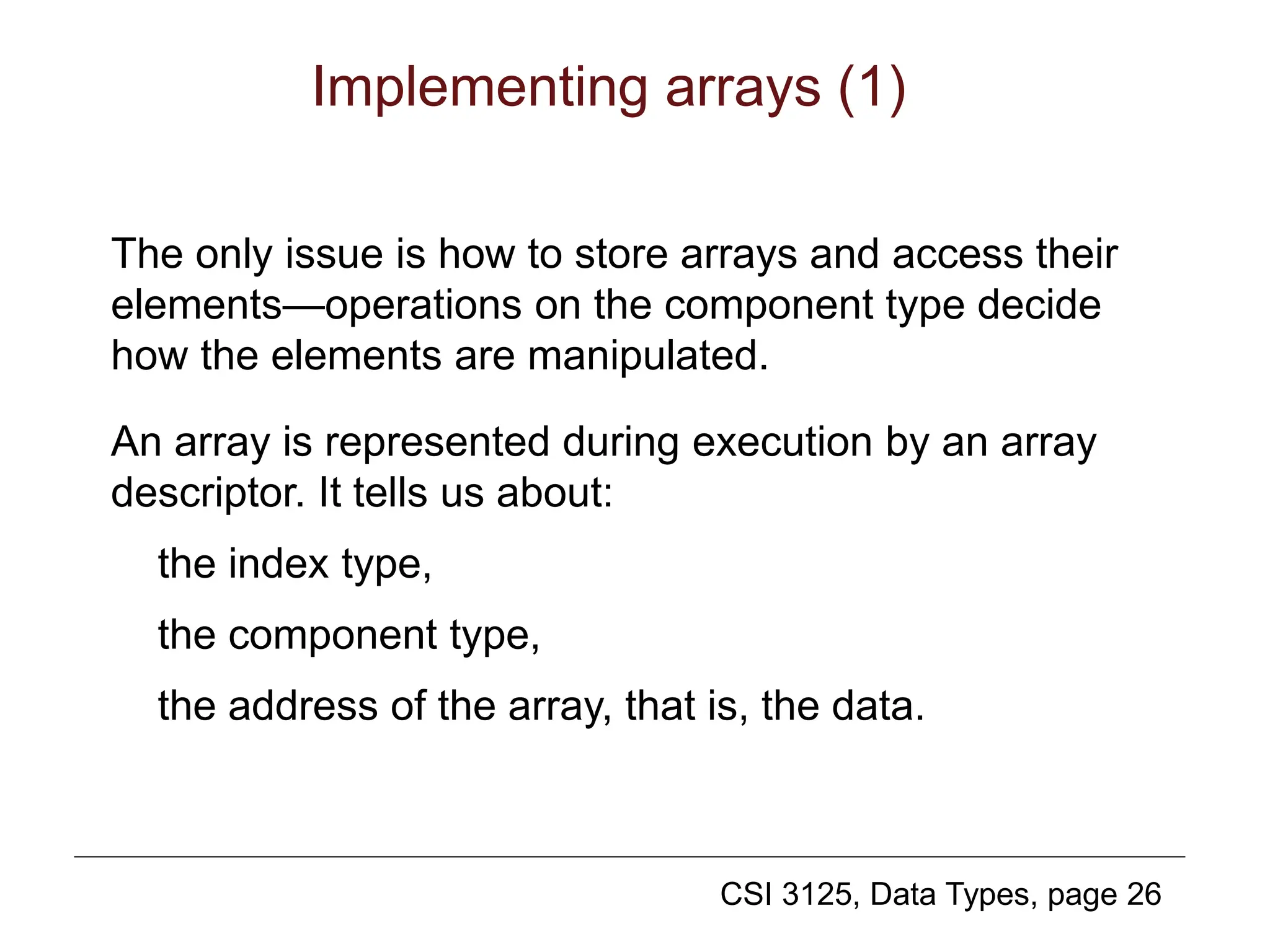

Array-type constants and initialization

Many languages allow initialization of arrays to be

specified together with declarations:

C int vector [] = {10,20,30};

Ada vector: array(0..2)

of integer := (10,20,30);

Array constants in Ada

temp is array(mo..su)of -40..40;

T: temp;

T := (15,12,18,22,22,30,22);

T := (mo=>15, we=>18, tu=>12,

sa=>30, others=>22);

T := (15,12,18, sa=>30, others=>22);](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/09datatypes-240420100358-35269b6b/75/09_java_DataTypesand-associated-class-ppt-25-2048.jpg)

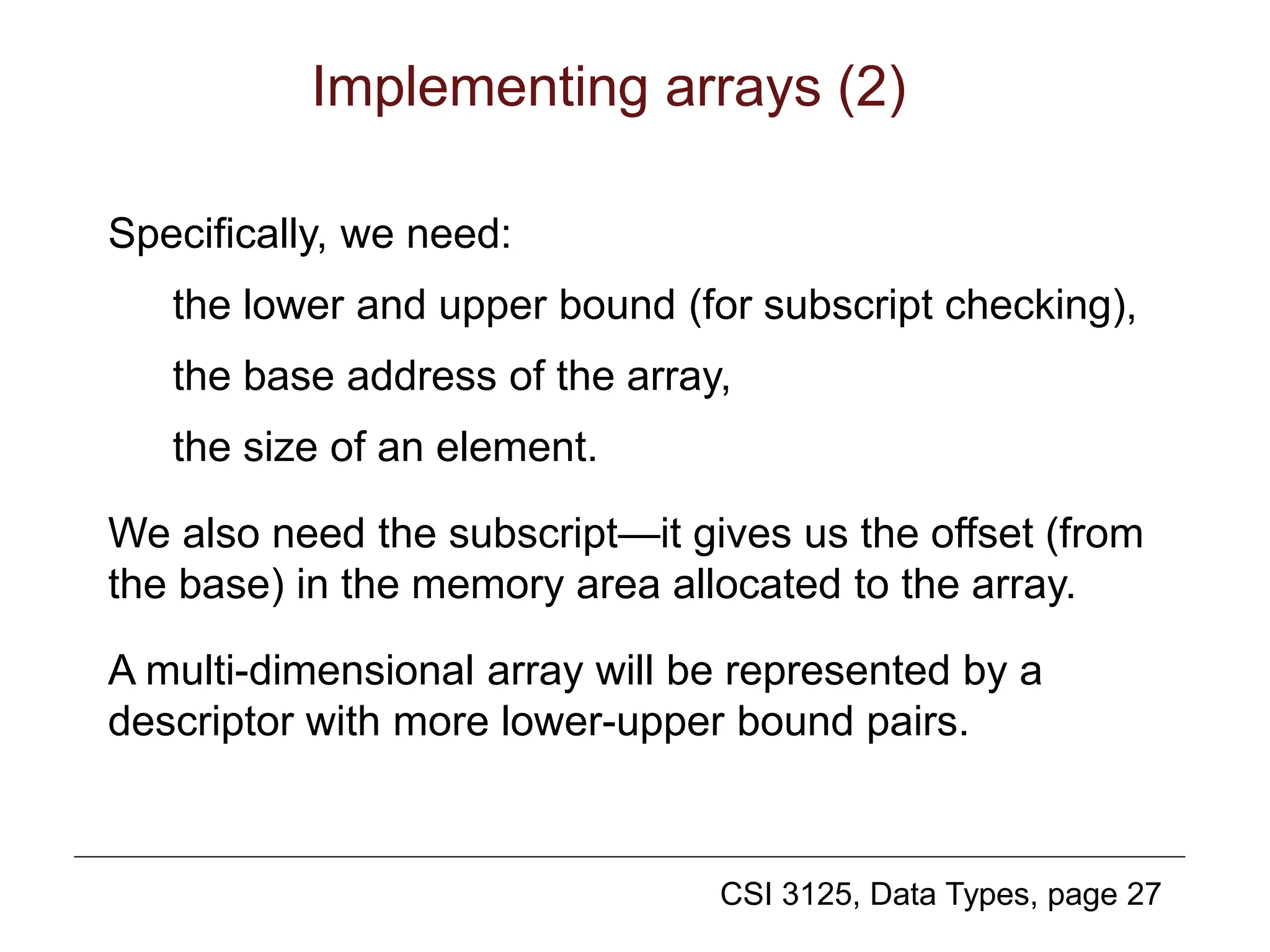

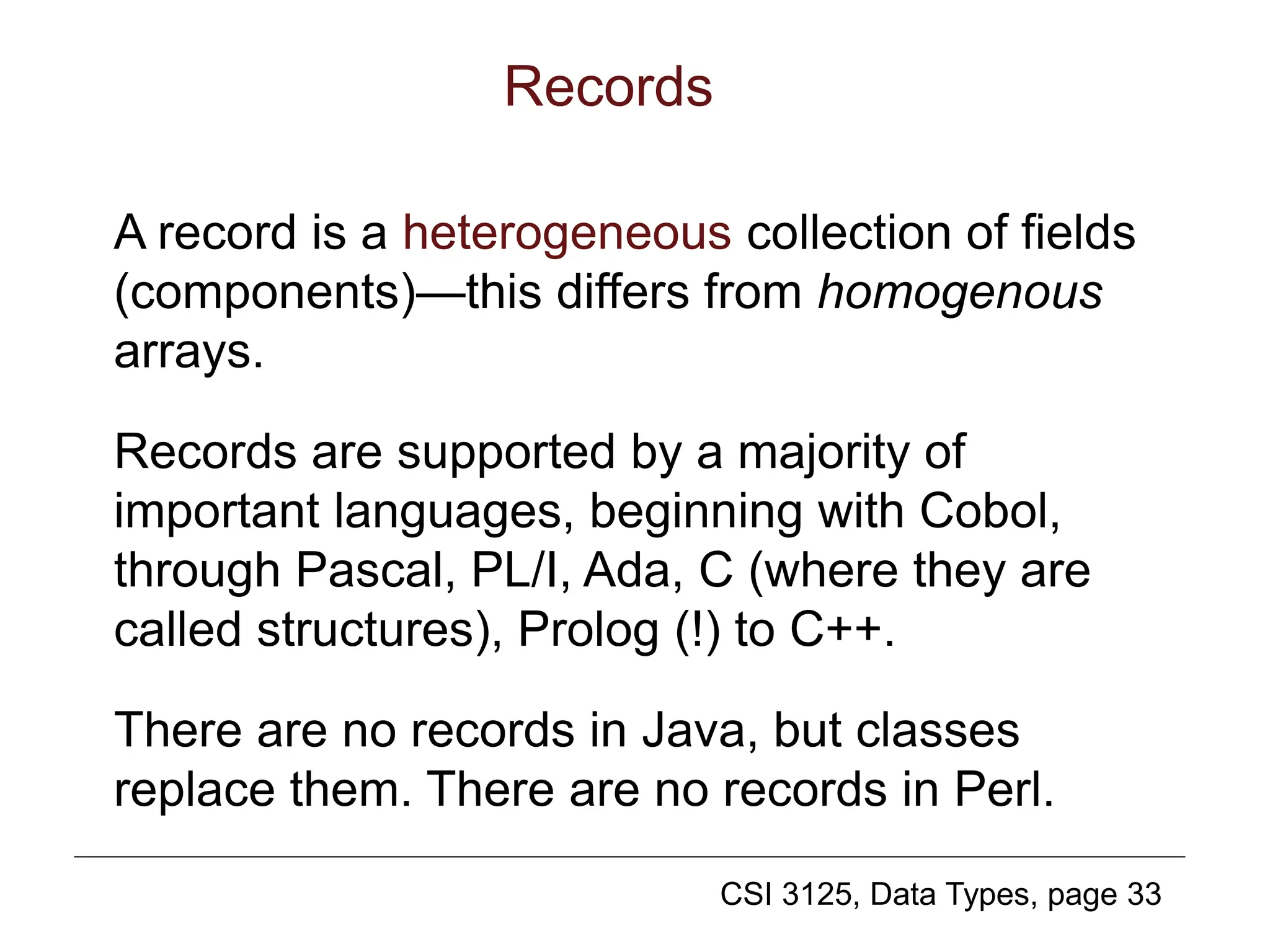

![CSI 3125, Data Types, page 29

Suppose that we have this array:

A: array [LOW1..HIGH1,

LOW2..HIGH2] of ELT;

where the size of each entity of type ELT is

SIZE.

This calculation is done for row-major

(calculations for column-major are quite

similar). We need the base—for example,

the address LOC of A[LOW1, LOW2].

Implementing multidimensional arrays (2)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/09datatypes-240420100358-35269b6b/75/09_java_DataTypesand-associated-class-ppt-29-2048.jpg)

![CSI 3125, Data Types, page 30

We can calculate the address of A[I,J] in the

row-major order, given the base.

Let the length of each row in the array be:

ROWLENGTH = HIGH2 - LOW2 + 1

The address of A[I,J] is:

(I - LOW1) * ROWLENGTH * SIZE +

(J - LOW2) * SIZE + LOC

Implementing multidimensional arrays (3)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/09datatypes-240420100358-35269b6b/75/09_java_DataTypesand-associated-class-ppt-30-2048.jpg)

![CSI 3125, Data Types, page 31

Here is an example.

VEC: array [1..10, 5..24] of integer;

The length of each row in the array is:

ROWLENGTH = 24 - 5 + 1 = 20

Let the base address be 1000, and let the size of

an integer be 4.

The address of VEC[i,j] is:

(i - 1) * 20 * 4 + (j - 5) * 4 + 1000

For example, VEC[7,16] is located in 4 bytes at

1524 = (7 - 1) * 20 * 4 +

(16 - 5) * 4 + 1000

Implementing multidimensional arrays (4)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/09datatypes-240420100358-35269b6b/75/09_java_DataTypesand-associated-class-ppt-31-2048.jpg)

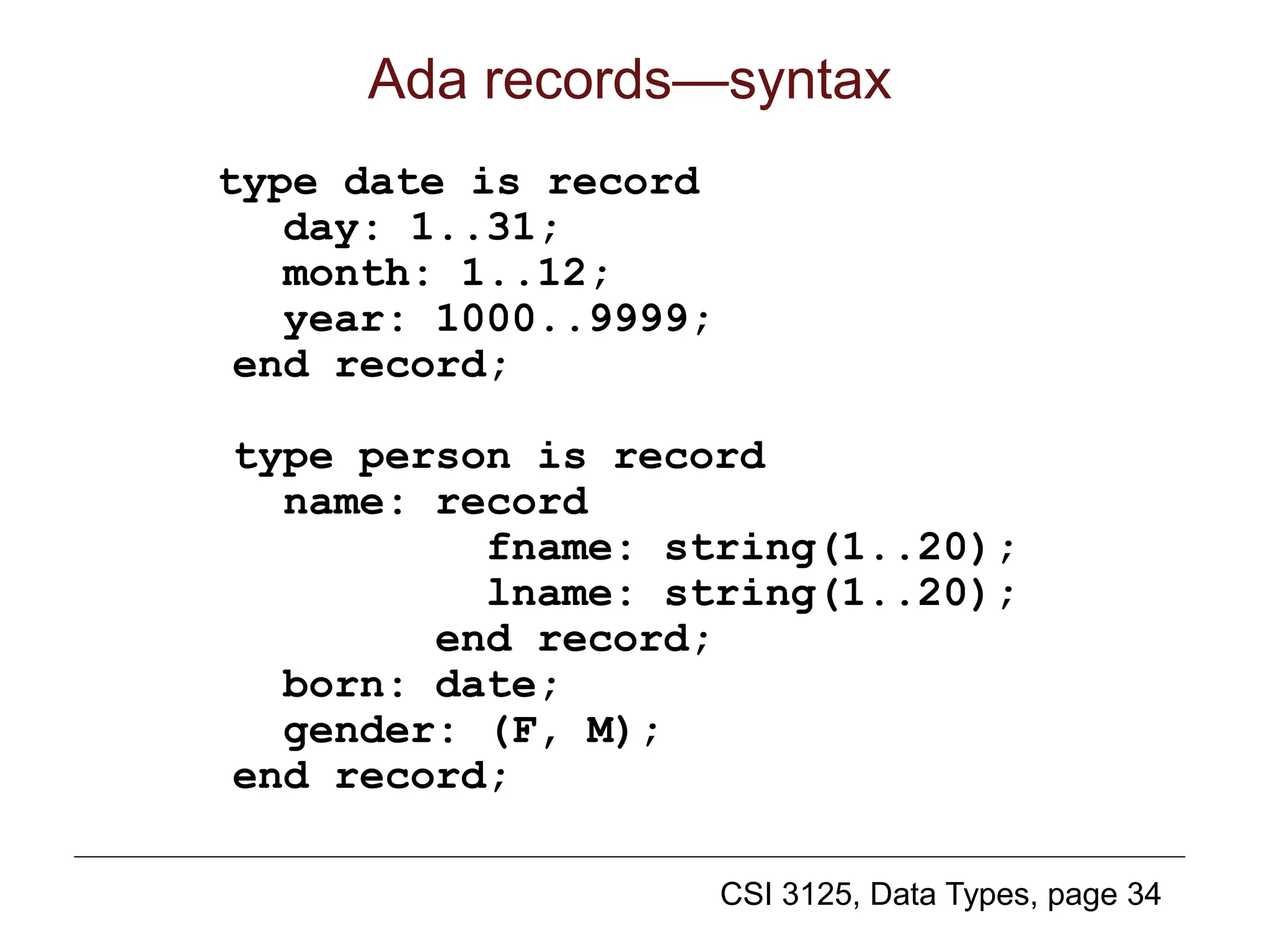

![CSI 3125, Data Types, page 32

Languages without arrays

A final word on arrays: they are not supported

by standard Prolog and pure Scheme. An array

can be simulated by a list, which is the basic

data structure in Scheme and a very important

data structure in Prolog.

Assume that the index type is always 1..N.

Treat a list of N elements:

[x1, x2, ..., xN] (Prolog)

(x1 x2 ... xN) (Scheme)

as the (structured) value of an array](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/09datatypes-240420100358-35269b6b/75/09_java_DataTypesand-associated-class-ppt-32-2048.jpg)

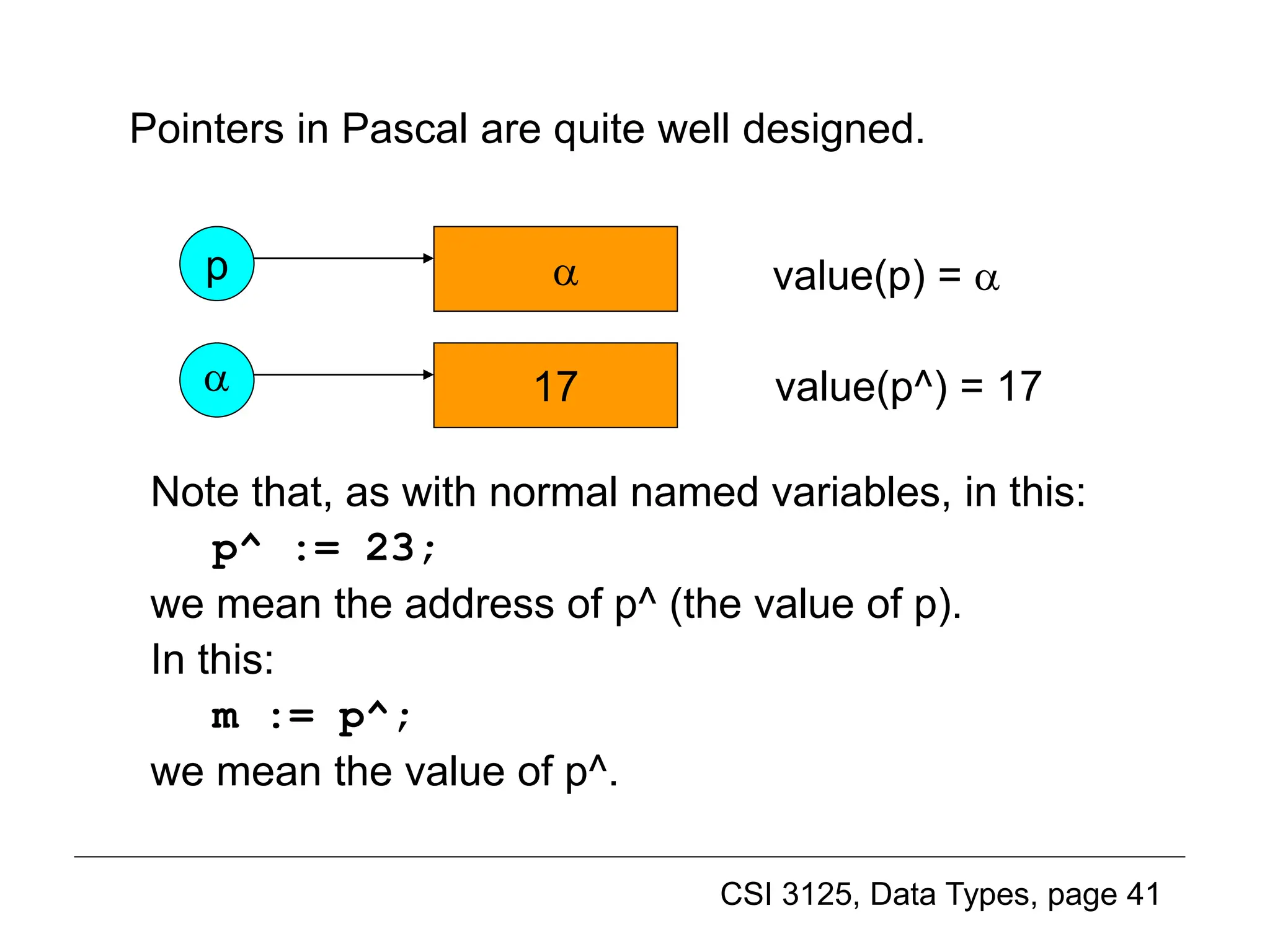

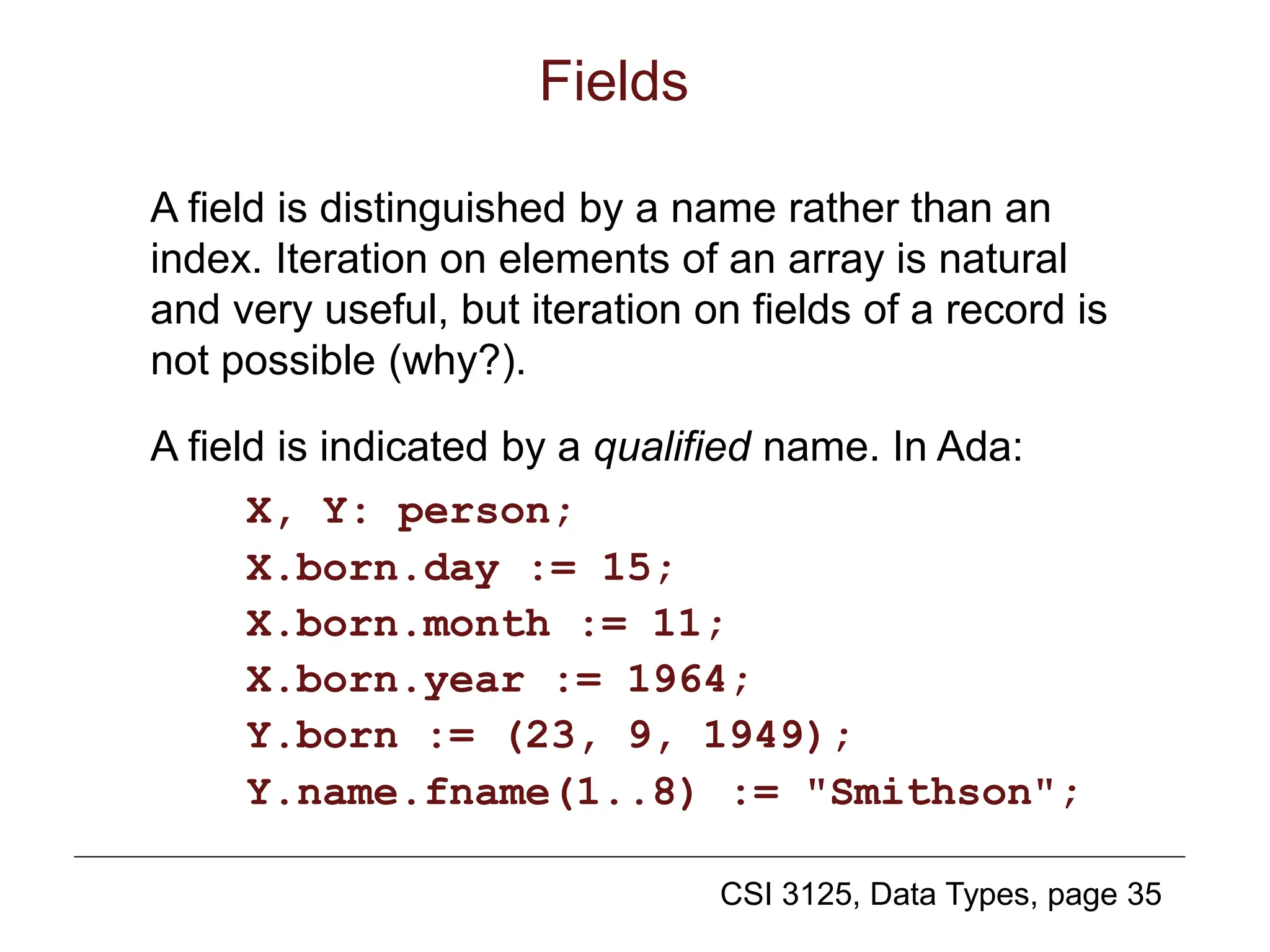

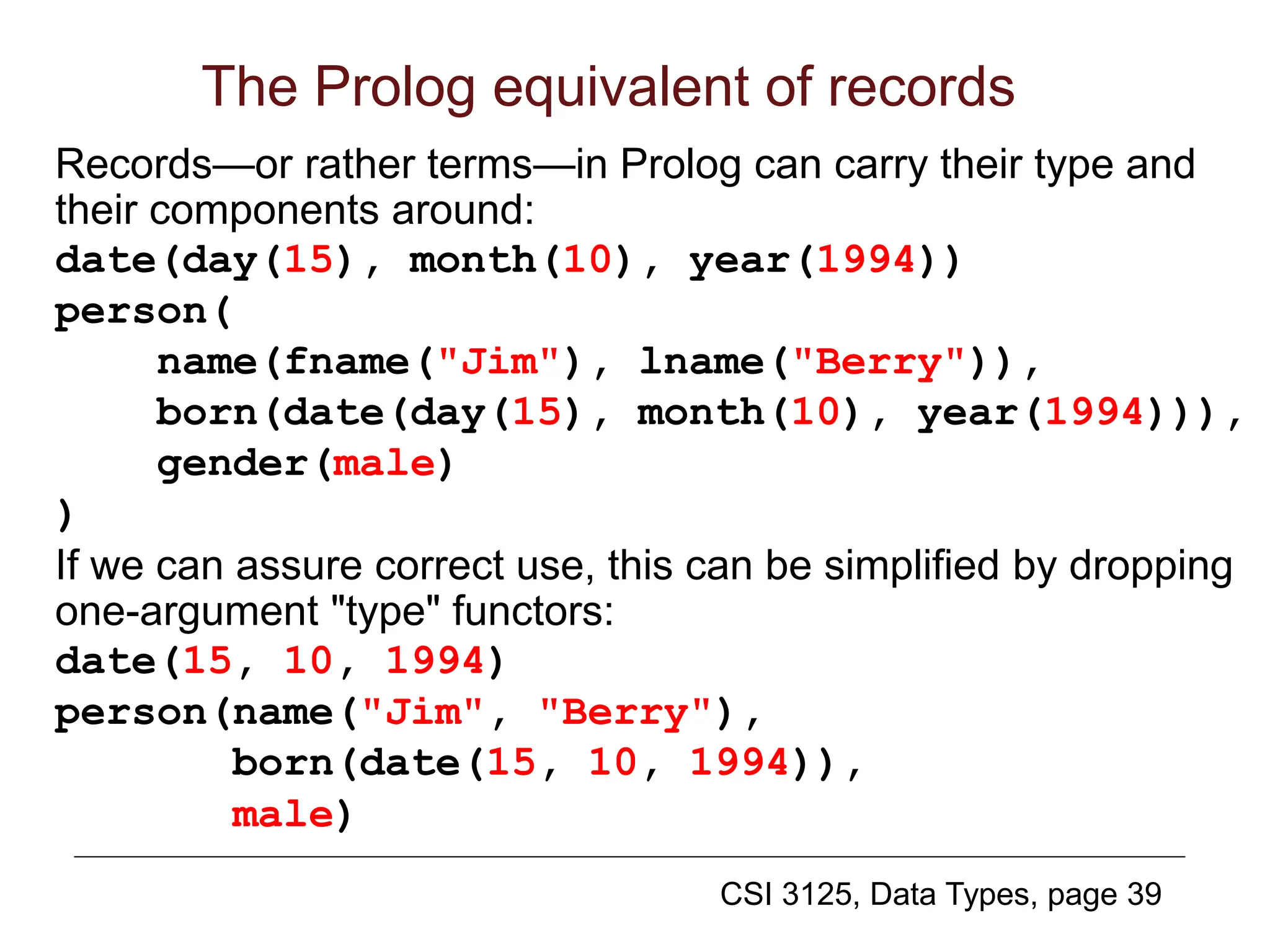

![CSI 3125, Data Types, page 40

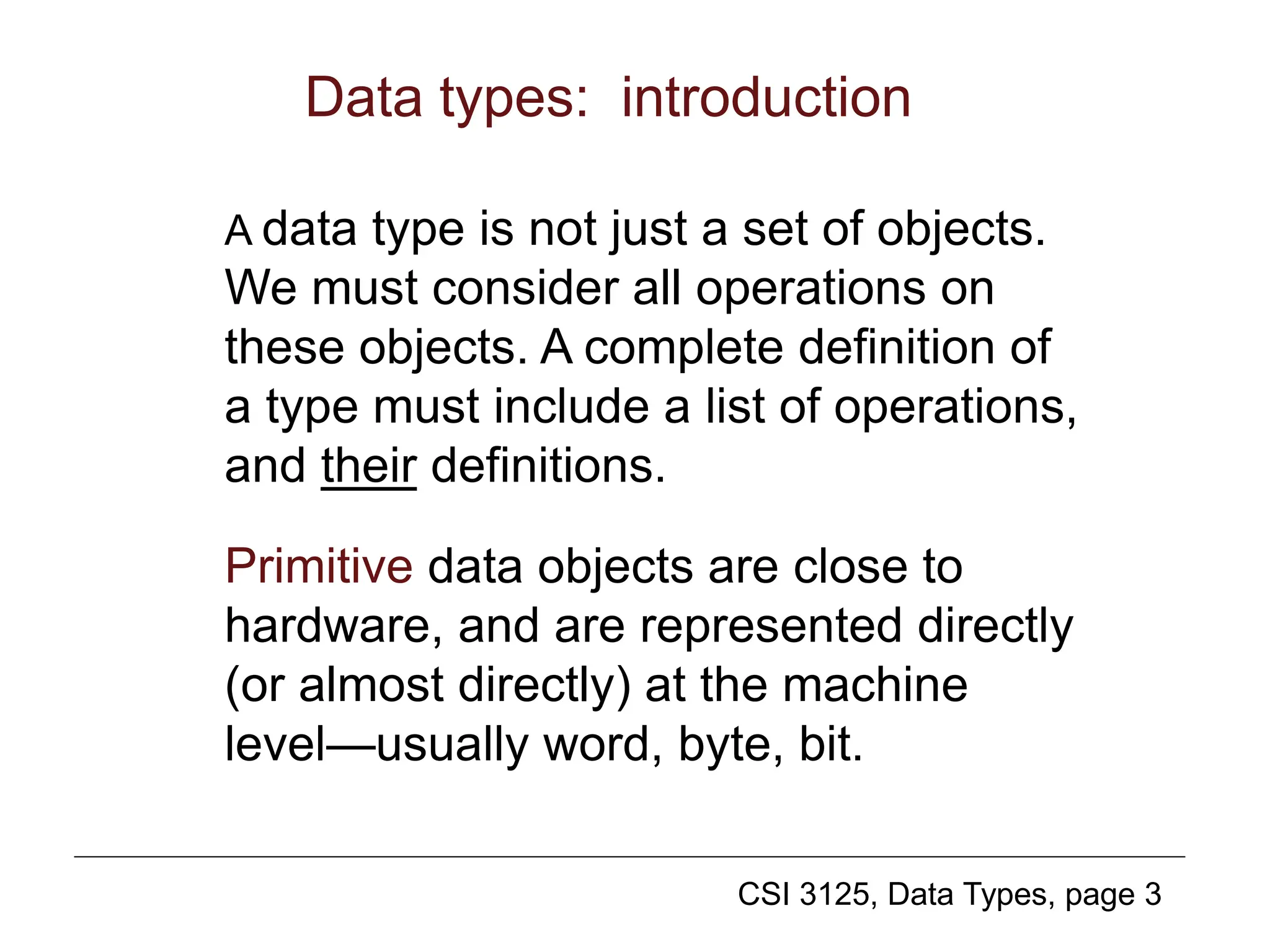

Back to pointers

[Note: We’re skipping 6.9.9]

A pointer variable has addresses as values (and a

special address nil or null for "no value"). They are used

primarily to build structures with unpredictable shapes

and sizes—lists, trees, graphs—from small fragments

allocated dynamically at run time.

A pointer to a procedure is possible, but normally we

have pointers to data (simple and composite). An

address, a value and usually a type of a data item

together make up a variable. We call it an anonymous

variable: no name is bound to it. Its value is accessed

by dereferencing the pointer.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/09datatypes-240420100358-35269b6b/75/09_java_DataTypesand-associated-class-ppt-40-2048.jpg)