070417 PARALLEL SOVEREIGNITY-Republic Of Lakotah

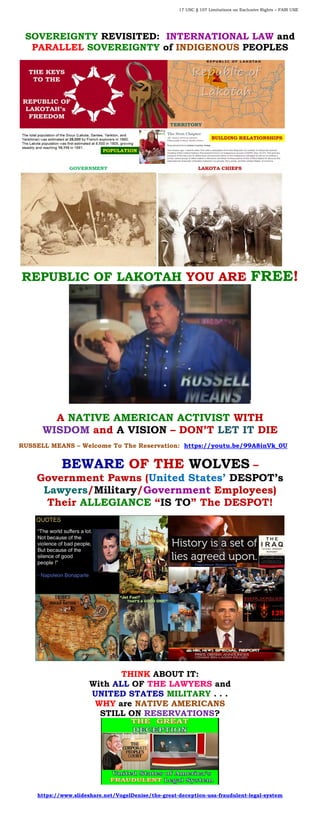

- 1. 17 USC § 107 Limitations on Exclusive Rights – FAIR USE SOVEREIGNTY REVISITED: INTERNATIONAL LAW and PARALLEL SOVEREIGNTY of INDIGENOUS PEOPLES REPUBLIC OF LAKOTAH YOU ARE FREE! A NATIVE AMERICAN ACTIVIST WITH WISDOM and A VISION – DON’T LET IT DIE RUSSELL MEANS – Welcome To The Reservation: https://youtu.be/99A8inVk_0U BEWARE OF THE WOLVES – Government Pawns (United States’ DESPOT’s Lawyers/Military/Government Employees) Their ALLEGIANCE “IS TO” The DESPOT! THINK ABOUT IT: With ALL OF THE LAWYERS and UNITED STATES MILITARY . . . WHY are NATIVE AMERICANS STILL ON RESERVATIONS? https://www.slideshare.net/VogelDenise/the-great-deception-usa-fraudulent-legal-system

- 2. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 155 Sovereignty Revisited: International Law and Parallel Sovereignty of Indigenous Peoples FEDERICO LENZERINI † SUMMARY I. INTRODUCTION: THE EVOLUTION OF THE CONCEPT OF SOVEREIGNTY FROM POLITICAL THEORY TO INTERNATIONAL LAW ....................................156 II. SOVEREIGNTY, SELF-DETERMINATION OF PEOPLES, AND DEMOCRACY ....160 III. INDIGENOUS SOVEREIGNTY ..............................................................................163 IV. MAJOR POTENTIAL TITLES OF INDIGENOUS SOVEREIGNTY .........................166 A. Recognizing the Invalidity of the Original Title of Indigenous Lands Occupation and of the Native Title’s Legal Significance.........................167 1. The relevant practice............................................................................167 2. The inadequacy of the recognition of the invalidity of the title of terra nullius and of the legal significance of the Native Title, ex se, as foundation of indigenous sovereignty......................................174 B. Delegation of Powers by the State..............................................................177 1. The practice of the delegation of sovereign powers by States in international law...................................................................................177 2. The lack of relevant practice concerning the delegation of sovereign powers by States to indigenous peoples...........................177 C. Rules of Customary International Law.....................................................180 1. The growing interest of international law for the protection of the identity and the rights of indigenous peoples.............................180 2. The foundations of the existence of a norm of customary international law concerning indigenous sovereignty ......................181 V. THE NATURE AND EXTENT OF INDIGENOUS SOVEREIGNTY UNDER CUSTOMARY INTERNATIONAL LAW.................................................................183 VI. CONCLUSION .......................................................................................................183 † Ph.D., International Law, Researcher, University of Siena, Italy. This article is the revised version of a paper presented at an international symposium on “A Modern Concept of Sovereignty: Perspectives from the US and Europe,” jointly organized by the UT Law School and the University of Siena on 31 May-1 June 2004 in Siena and on 14-16 April 2005 in Austin, TX.

- 3. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 156 TEXAS INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL VOL. 42:155 I. INTRODUCTION: THE EVOLUTION OF THE CONCEPT OF SOVEREIGNTY FROM POLITICAL THEORY TO INTERNATIONAL LAW The controversial nature of the topic of indigenous sovereignty is inherent in its very theorization, in that it constitutes a powerful challenge to the basic foundations of international law. In order to properly understand whether and to what extent such sovereignty actually exists within the framework of contemporary international law, it is necessary to have a retrospective look at the evolution and development of the concept of sovereignty in the modern world. Such preliminary investigation serves the purpose of ascertaining whether the notion of sovereignty in international law must be conceived in an absolute sense or, on the contrary, whether its scope is subject to the influence of other competing values that could therefore represent the foundations for asserting the existence of a given degree of indigenous sovereignty parallel to the sovereign power held by the State. At the time that the philosophy of sovereignty, in the modern sense of the term, first developed it was certainly conceived as an absolute prerogative of the sovereign entity. In Shakespeare’s Richard II, the former King of England, forced by Henry IV to hand over his crown, is killed in prison by Sir Pierce of Exton, who thought that it was Henry IV’s wish that Richard II be dead. When Sir Pierce of Exton brings Richard II’s body before Henry IV, the new King bitterly blames the murderer: Exton, I thank thee not, for thou hast wrought A deed of slander with thy fatal hand Upon my head and this famous land.1 Then, he banishes him from the Kingdom: With Cain go wander through shades of night, And never show thy head by day nor light.2 The prophecy of disgrace incumbent upon Henry IV and England is a corollary of the idea of the impossibility of destroying, even by assassination, the enduring nature of the King, representing the mystical dignity and justice of sovereignty.3 The inherent dignity of the King was above the earthly idea of life and death, and also above the law. The conception of the sovereign power as the supreme entity, over the law and the life and death of the subjects, was shared by most theorists and philosophers from the early modern times, such as Nicolò Machiavelli, Jean Bodin, and Thomas Hobbes, although such an idea was often the result of considerations of realpolitik rather than of supernaturalism-based thoughts. In the words of Machiavelli: 1. WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE, RICHARD II act 5, sc. 6 (John Dover Wilson ed., Cambridge Univ. Press 1961) (1597). 2. Id. 3. See ERNST HARTWIG KANTORWICZ, THE KING’S TWO BODIES: A STUDY IN MEDIEVAL POLITICAL THEOLOGY 405-09 (Princeton University Press 1997) (1957); see also Dan Philpott, Sovereignty, THE STANFORD ENCYCLOPEDIA OF PHILOSOPHY para. 1 (Edward N. Zalta ed., 2003) (explaining the enduring nature of political entities), http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/sovereignty (last visited Oct. 6, 2006).

- 4. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 2006 SOVEREIGNTY REVISITED 157 Those who have been present at any deliberative assemblies of men will have observed how erroneous their opinions often are; and in fact, unless they are directed by superior men, they are apt to be contrary to all reason.4 . . . . The only way to establish any kind of order there is to found a monarchical government; for where the body of the people is so thoroughly corrupt that the laws are powerless for restraint, it becomes necessary to establish some superior power which with a royal hand, and with full and absolute powers, may put a curb upon the excessive ambition and corruption of the powerful.5 In sum, it was just the public interest that required an absolute type of sovereignty, which justified the use, by the prince, of any kind of instrument, irrespective of its moral implications, including force (“the stick”), bribery, or deceit. From these premises, the objective idea of sovereignty that emerged in early modern Europe was of a power concentrated in the hands of an authority bundled into a single entity, which governed a collectivity unified by the sharing of a single set of interests and confined within territorial borders. The sovereign authority held supremacy in the collective interest.6 When Europe came out of the Medieval darkness (politically speaking), the internal absoluteness of sovereignty was not yet reflected in its external dimension. In particular, the Holy Roman Empire retained a nearly exclusive power over religious matters, and this allowed the Pope to interfere in the internal affairs of independent “sovereign” States. The transition from the “vertical” structure— headed by the Pope and the Holy Roman Empire—to the “horizontal” structure of independent sovereign States—which in principle were equal in authority and legal legitimacy—was consolidated in 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia (ending the Thirty Years’ War in Europe), which introduced the so-called Westphalian sovereignty. A number of States acquired uncontested independence, no longer the subject of interferences from the Holy Roman Empire; the authority of princes and kings over religion, with regard to the territories subjected to their sovereignty, was definitely established.7 The principle of non-interference by any sovereign power in the territorial affairs of other States became the main uncontested rule that governed the system of international relations, and the authority of kings and princes over their respective territories became “supreme.” This evolution resulted in a concept of sovereignty that may be defined as “supreme authority within a territory.”8 The first element of this definition is “authority,” which has been defined by the philosopher R. P. Wolff as “the right to command and correlatively the right to be obeyed”;9 the term “right” is central to the definition since it indicates the legitimacy of sovereignty—founded on some 4. NICCOLO MACHIAVELLI, THE PRINCE & THE DISCOURSES 354 (Christian E. Detmold trans., A.S. Barnes & Co., Inc. 1940) (1882). 5. Id. at 255. 6. See Philpott, supra note 3, para. 1. 7. Id. para. 2. 8. Id. para. 1 (emphasis omitted). 9. Robert Paul Wolff, The Conflict Between Authority and Autonomy, in AUTHORITY (Joseph Raz ed., 1990).

- 5. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 158 TEXAS INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL VOL. 42:155 legitimate basis.10 The second component of the concept is that “authority” is “supreme,” in the sense that the sovereign power is superior to any other authority which, to whatever extent, exercises governing functions over the territory concerned;11 in a federal State, for example, the central government, identified in the constitution of the federation, is superior to the governments of any “sub-State,” which is part of the federation itself. Finally, a sovereign authority needs a territory, delineated by political borders, over which it has the right of exercising its supreme powers. Seen in these terms, sovereignty appears as having an absolute character, characterized by the fact that no external entity may, in principle, interfere with its exercise. The world is thus composed by a number of sovereign entities that have absolute dominion within their territorial borders, all of these sovereign entities being in a relationship of parallel equality with each other. In other words, they all possess an identical set of sovereign features, and the sovereign powers belonging to each of such entities stop exactly where the sovereign powers of another begin. This is the so-called chunk theory of sovereignty, according to which sovereignty may only be possessed “in full or not at all,” being represented as a monolithic chunk of identical stones, any one of which is possessed by a sovereign entity.12 From the standpoint of international law, the translation of this theory into practical terms shows the connection between the concept of sovereignty, at least in its strict and narrowest sense, with the notion of constitutional or legal independence. Etymologically speaking, one entity is independent when it is not dependent on any other authority. In this context, the element of the territory is of particular relevance since, according to international law, independence is linked to a territorial area. It thus exists when the sovereign entity is able, at least to a satisfactory extent, to freely dispose of its own territory without external interferences; a sovereign power must have a government of its own, one not subject to the control of another governmental body. In principle, in contemporary international law, the entity which meets the necessary conditions for sovereignty is the State. As a consequence, although the concept of sovereignty is to be distinguished from the related concept of statehood, it is in fact strictly related to the existence of a State. The other sovereign entities different from States (this latter term being conceived in a strict sense), existing in the framework of contemporary international law (like the European Union), derive from States and are the result of a voluntary and conscious delegation of powers by States themselves. The conception of sovereignty as a prerogative of States as independent entities enjoying political dominion over a territorial area is clearly expressed by article 2 paragraph 4 of the Charter of the United Nations, which bans the threat or use of force “against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state.”13 Having said this, the fact that the “sovereign equality” of States, which, in terms of legal theory, is a corollary of the principle of sovereignty itself,14 exists only in principle, since the degree of independence exercised by States varies greatly in 10. See Philpott, supra note 3, para. 1. 11. Id. 12. MICHAEL ROSS FOWLER & JULIE MARIE BUNCK, LAW, POWER, AND THE SOVEREIGN STATE: THE EVOLUTION AND APPLICATION OF THE CONCEPT OF SOVEREIGNTY 64 (1995) (quoting INIS L. CLAUDE, JR., NATIONAL MINORITIES: AN INTERNATIONAL PROBLEM 32 (1955)). 13. U.N. CHARTER art. 2, para. 4. 14. John H. Jackson, Sovereignty-Modern: A New Approach to an Outdated Concept, 97 AM. J. INT’L L. 782 (2003) (noting that equality among nations solidifies the notion of sovereignty).

- 6. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 2006 SOVEREIGNTY REVISITED 159 reality. It is necessary to emphasize that even for the most powerful States in the world sovereignty is not absolute. For instance, a number of States have definitively delegated a wide range of powers to other entities, as has happened with the European Union. Thus, the so-called basket theory of sovereignty appears as much more coherent to the concrete reality existing in the real world than the chunk theory.15 According to the basket theory, sovereignty is to be seen “in variable terms, as a basket of attributes and corresponding rights and duties.”16 Any sovereign entity owns a basket, but the content of the different baskets varies considerably; certain sovereign entities have baskets with many more attributes of sovereignty than others, and as a result, entities possessing more of these attributes have a higher degree of independence. In addition, the extent of State sovereignty has been progressively circumscribed by the evolution of international law, which, through freeing itself from its original character as a corpus juridicum composed exclusively of norms reflecting reciprocal concessions made by States vis-à-vis other governments with the purpose of satisfying shared individual interests, has increasingly permeated the area of State domestic jurisdiction for the safeguarding of values of universal relevance, corresponding to interests shared by the international community as a whole. This has resulted in a global context in which State sovereignty is constrained by a number of international principles, in particular those concerning the prohibition of the use of force, the delimitation of the special sphere of powers, the obligations concerning the treatment of aliens, the protection of human rights and, more recently, the protection of the environment and of cultural heritage, and is thus limited in its scope.17 Although the beginning of such evolution of international law is commonly traced back to the end of World War II, as a reaction to the awful crimes committed during that tragic conflict, it actually began in the early nineteenth century (with Emmerich de Vattel’s The Law of Nations) when some scholars felt that the concept of sovereignty could no longer be thought of in absolute terms, recognizing that a “sovereign” could be under the authority (de jure or de facto) of another greater sovereign without losing its own “sovereignty.”18 In addition, since the first half of the twentieth century, a number of scholars, conceiving the term “State” in a broad sense, theorized the distinction between “sovereign” (i.e. “independent”) and “semi-sovereign” (i.e., “dependent”) States, both possessing, although to a different extent, the attributes of sovereignty.19 As a result of the previous considerations, it appears that, from the perspective of international law, it is no longer appropriate to refer to sovereignty as supreme authority within a territory, but rather as territorial independence subject to no legal 15. FOWLER & BUNCK, supra note 12, at 72-73. 16. Id. at 70. 17. See, e.g., Kofi Annan, Two Concepts of Sovereignty, THE ECONOMIST, Sept. 18, 1999 (“State sovereignty, in its most basic sense, is being redefined—not least by the forces of globalization and international co-operation.”). 18. U.N. ECOSOC, Comm. on Hum. Rts., Sub-Comm. on the Promotion and Protection of Hum. Rts., Final Report of the Special Rapporteur: Indigenous Peoples’ Permanent Sovereignty over Natural Resources, 19, U.N. Doc. E/CN.4/Sub.2/2004/30 (July 13, 2004) (prepared by Erica-Irene A. Daes) (quoting EMMERICH DE VATTEL, THE LAW OF NATIONS 60 (American ed. 1805)). 19. See 1 GREEN HAYWORD HACKWORTH, DIGEST OF INTERNATIONAL LAW §§ 10-11 (1940) (noting the difference between a state and a nation and the sub-categorization of states as “sovereign,” “independent,” “dependent,” or “semi-sovereign”).

- 7. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 160 TEXAS INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL VOL. 42:155 constraints except those imposed by international law. In this regard, it is evident that the actual extent of such independence depends on the degree and the scope of the constraints imposed on any sovereign entity by international law. II. SOVEREIGNTY, SELF-DETERMINATION OF PEOPLES, AND DEMOCRACY The evolution of international law that has taken place in the last decades has led not only to the restriction of the scope of State sovereignty, but also to the conditioning of its constitutive elements, particularly its legitimacy. While it may be argued that, until the second half of the twentieth century, the legitimacy of sovereignty was ipso facto inherent in the reality of an effective power over a territory and a community of people, in more recent times this situation has slightly changed due to the development of a movement, still in fieri at present, pursuing the idea that to be legitimate, sovereignty must be representative of the people living in the territory upon which it extends its scope. Under traditional international law, the forms of sovereignty and its ways of management were part of the domestic jurisdiction of States. As a consequence, the idea of sovereignty that developed in the early modern times,20 as well as its practical applications (including dictatorial governments), were in no way inconsistent with international law, for the simple reason that it was not a matter that international law could interfere with. This notwithstanding, since the eighteenth century, the philosophy of sovereignty was progressively modified, with the rising of popular movements aimed at freeing peoples from the domination of despotic governments. For example, article 3 of the Declaration of the Rights of Men and of the Citizen, approved by the National Assembly of France on August 26, 1789, solemnly declared that “[l]e principe de toute souveraineté réside essentiellement dans la Nation. Nul corps, nul individu ne peut exercer d’autorité qui n’en émane expressément.”21 Also more solemnly, the U.S. Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776 had previously considered the principle of democracy as originating from the “Laws of Nature” and by God Himself.22 Legally speaking, for nearly two centuries, the relevance of these proclamations remained limited in scope to the States concerned, although they operated as sparks for the rising of revolutionary movements pursuing the idea of democracy in 20. See HACKWORTH, supra note 19, § 1. 21. “The principle of all sovereignty resides essentially in the nation. No body nor individual may exercise any authority which does not proceed directly from the nation.” DÉCLARATION DES DROITS DE L'HOMME ET DU CITOYEN [DECLARATION OF THE RIGHTS OF MAN AND OF THE CITIZEN] art. 3 (France 1789), translation available at http://www.hrcr.org/docs/frenchdec.html. 22. “When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation. We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. --That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, --That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness.” THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE para. 1-2 (U.S. 1776).

- 8. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 2006 SOVEREIGNTY REVISITED 161 different countries. Starting in the 1950s, the practice of the United Nations led to the evolution of the principle of self-determination of peoples, already proclaimed by article 1 paragraph 2 and article 55 of the U.N. Charter, towards a principle of customary international law granting the right of independence to any people subjected to foreign colonial domination. Such a principle, at least in its external sense, exhausts its relevance to the situations of forcibly imposed foreign occupation, without supporting the secessionist aspirations of minorities or ethnically-distinct groups or meaning that any government of the world must be the expression of the majority of its population. Thus, at present, it may not yet be maintained that a principle of general international law establishing that any sovereign power must be founded on democracy actually exists, since a number of non-democratic governments still exist in the world and are tolerated by the international community. This notwithstanding, it may not be sustained that international law is totally unconcerned with this matter. Leaving aside the recent proclamations aimed at justifying the violation of the sovereignty of others by using armed force with the need of “exporting democracy,” the element of democracy is now part of the dialogue among States (not only within the framework of developed countries) to a progressively growing extent, so as to raise some doubts of the international legality of certain particularly oppressive forms of government. At the declarative level, the principle of democracy was, for example, proclaimed in 1990 by the final document of the Copenhagen Meeting of the Conference on the Human Dimension of the Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE) (representing thirty- four countries, including the USSR, plus the Holy See), which recognized, among other things, that pluralistic democracy and the rule of law are essential for ensuring respect for all human rights and fundamental freedoms, the development of human contacts and the resolution of other issues of a related humanitarian character [and welcomed] the commitment expressed by all participating States to the ideals of democracy and political pluralism as well as their common determination to build democratic societies based on free elections and the rule of law.23 More recently, with the Warsaw Declaration of June 27, 2000, the “Community of Democracies,” representing 106 States from all the different geographic, political, and cultural areas of the world, agreed to respect and uphold some core democratic principles and practices, including the rule that “[t]he will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government, as expressed by exercise of the right and civic duties of citizens to choose their representatives through regular, free and fair elections with universal and equal suffrage . . . .”24 The fact that the principle of democracy is pursued not solely by Western countries is also demonstrated by other relevant international instruments, although not binding per se, adopted at the regional level. For example, the Charter of the Organization of American States (OAS) identifies the aim of “promot[ing] and consolidat[ing] representative democracy” as one of the “essential purposes” of the 23. Conference on Security and Co-Operation in Europe: Document of the Copenhagen Meeting of the Conference of the Human Dimension, June 29, 1990, 29 I.L.M. 1305, 1306. 24. Final Warsaw Declaration: Towards a Community of Democracies, June 27, 2000, 39 I.L.M. 1306.

- 9. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 162 TEXAS INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL VOL. 42:155 Organization.25 Also at the OAS level, the Inter-American Democratic Charter solemnly states that “[t]he peoples of the Americas have a right to democracy and their governments have an obligation to promote and defend it.”26 Similarly, the 2004 Dar-Es-Salaam Declaration on Peace, Security, Democracy and Development in the Great Lakes Region, adopted under the auspices of the United Nations and the African Union, emphasizes the “need to respect democracy and good governance”27 and to develop “a regional and inclusive vision for the promotion of sustainable peace, security, democracy and development.”28 At the EU level, virtually all agreements concluded by the European Community (EC) with developing countries are characterized by non-reciprocal trade preferences. These preferences are granted with the aim of promoting the social and economic development of the developing countries, and contain a “clause of democracy” conditioning the implementation of the agreements by the EC on the respect for the principle of democracy by the developing State. Furthermore, for the purpose of the present analysis it is of paramount importance that the right “to take part in the government of [one’s own] country, directly or through freely chosen representatives” is included among fundamental human rights by nearly all pertinent international instruments.29 Such a right, as pointed out by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, becomes effective when [t]he will of the people [is] the basis of the authority of government; this will [is to] be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which [must] be by universal and equal suffrage and [must] be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures.30 In the light of the preceding observations, it appears that the question of whether a government is democratic or dictatorial is no longer a matter laying “essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state,”31 and that, a fortiori, although an international rule proclaiming the obligation for governments to be founded on the free choice of their citizens does not yet exist ex se, the absolute denial of any kind of democratic participation of the citizens in the life of the country is no longer being tolerated by the international community. It is not just a problem of democracy in a strict sense, but it is a matter that also invades the realm of fundamental rights. The 2005 elections in Iraq, with the Iraqi people risking their lives under the bullets of the rebels just for the opportunity to exercise their right to vote,32 demonstrated how the right to participate in the choice of their own government is perceived as fundamental by all the peoples of the world. 25. Protocol of Amendment to the Charter of the Organization of American States art. 2(b), Dec. 14, 1992, 33 I.L.M. 987, 989, available at http://www.oas.org/juridico/english/charter.html. 26. Organization of American States, Inter-American Democratic Charter art. 1, Sept. 11, 2001, 40 I.L.M. 1289, 1290, available at http://www.oas.org/OASpage/eng/Documents/Democratic_Charter.htm. 27. Dar-Es-Salaam Declaration on Peace, Security, Democracy and Development in the Great Lakes Region, para. 4, Nov. 19-20, 2004, available at http://www.icglr.org/common/docs/docs_repository/declarationdar-es-salaam.pdf. 28. Id. para. 13. 29. Universal Declaration of Human Rights, U.N. GAOR, 3d Sess., pt. 1, at 75, U.N. Doc. A/810 (1948), available at http://www.unhchr.ch/udhr/lang/eng.pdf. 30. Id. art. 21(3). 31. U.N. CHARTER art. 2, para. 7. 32. See Paul Wood, Courage and Euphoria as Iraq votes, BBC NEWS, Jan. 31, 2005, available at

- 10. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 2006 SOVEREIGNTY REVISITED 163 III. INDIGENOUS SOVEREIGNTY The observations developed in the previous sections serve primarily to define the general context in light of which claims for “indigenous sovereignty,” increasingly being raised in present times, are to be evaluated. This survey generally indicated that sovereignty is commonly understood as an attribute of statehood, as a result of the very nature of international law, which, having been created by Western States, is mainly an expression of their interests and conceptions. If one looks at the whole matter from a “conservative” perspective, one will conclude that, in principle, this depiction of sovereignty has not significantly changed in the present times, despite the development of certain principles, such as the self-determination of peoples, which have only been capable of giving rise to specific exceptions to the principle of sovereignty applicable solely to well-defined and limited circumstances (i.e., in the event of colonial foreign domination). The contemporary international legal order thus appears particularly impervious to claims, like those of indigenous peoples, which threaten to disrupt the unfettered exercise of State sovereignty. 33 At the same time, the international community is progressively recognizing the legal relevance of a number of values (including the right of people to participate in the government) that actually erode the traditional idea of sovereignty as the unconditioned prerogative of the State. In addition, an objective assessment of the inherent characters of most indigenous nations34 demonstrates that they possess the qualities necessary for qualifying an entity as a State according to international law, as defined by scholars35 and relevant practice:36 a) a permanent population; b) a defined territory; c) government; and d) capacity to enter into relations with the other States (i.e., independence).37 There is no doubt that most indigenous peoples have always retained permanent populations and, at the time of their defeat, controlled a defined territory. With regard to the second requirement, the fact that the frontiers of their respective territories were often not precisely defined does not preclude that http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/middle_east/4224435.stm. 33. See Dianne Otto, A Question of Law or Politics? Indigenous Claims to Sovereignty in Australia, 21 SYRACUSE J. INT’L L. & COM. 65, 79 (1995). 34. In the present work, “indigenous peoples” are treated as a unified legal category, although the different indigenous communities existing in the world are characterized by remarkable differences which may require that all general conclusions concerning the general category of “indigenous peoples” being adapted to the specific peculiarities of each community concerned. As noted by Benedict Kingsbury, the concept of “indigenous peoples” as a global concept “is . . . of great normative power for many relatively powerless groups that have suffered grievous abuses, and it bears the imprimatur of representatives of many such groups who are themselves shaping it while being shaped by it.” Benedict Kingsbury, “Indigenous Peoples” in International Law: A Constructivist Approach to the Asian Controversy, 92 AM. J. INT’L L. 414, 415 (1998). In addition, in principle the conclusions which will be drawn in the present work are of a general character and thus applicable to most indigenous communities, provided that they are adapted to the peculiarities of each group concerned when translated into concrete action in the real world. 35. See, e.g., HACKWORTH, supra note 19, at 47 (“[T]he term state . . . connotes, in the international sense, a people permanently occupying a fixed territory, bound together by common laws and customs into a body politic, possessing an organized government, and capable of conducting relations with other states.”) But see IAN BROWNLIE, PRINCIPLES OF PUBLIC INTERNATIONAL LAW 70-72 (6th ed. 2003). 36. See Convention on Rights and Duties of States, Dec. 26, 1933, 49 Stat. 3097, available at http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/intdip/interam/intam03.htm. 37. John Howard Clinebell & Jim Thomson, Sovereignty and Self-Determination: The Rights of Native Americans under International Law, 27 BUFF. L. REV. 669, 673-79 (1978).

- 11. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 164 TEXAS INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL VOL. 42:155 requirement from being satisfied, provided that they had a defined political community.38 Some doubts could be raised with regard to nomadic tribes or peoples, on account of their lack of a stable and “defined territory.”39 However, the concept of statehood is to be contextualized at the time which is relevant with respect to establishing whether a given entity could be considered as sovereign when it was occupied by foreign invaders. In the case of the tribes inhabiting the Western Sahara, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) emphasized that “sovereignty was not generally considered as effected through occupation, but through agreements concluded with local rulers.”40 This can be applied to most indigenous peoples at the time when they were defeated by foreign settlers. Under this perspective, even those indigenous peoples that were nomadic at the time of the occupation of their own lands by foreign colonizers could meet the necessary requirements for being considered “States” according to international law applicable at the relevant time. In addition, the third criterion of statehood was certainly possessed by most indigenous peoples as long as they retained control on their lands, as has been confirmed by the ICJ in the Western Sahara case, although they used “schemes” of government not recognized as such by the European settlers at the relevant time.41 Finally, their independence, i.e., their ability to enter into relations with other States, is demonstrated by the myriad of treaties concluded by such peoples with other sovereign States.42 However, it was on account of the presumed lack of sovereignty of indigenous peoples over the lands traditionally occupied by them that, at the time that the European colonizers placed their feet on the new lands the doctrine of discovery was developed, based on the fictional status of terra nullius (i.e., owned by no one, free of any internationally-recognizable legal authority), used for justifying in “legal” terms the legitimacy of the occupation of the territories newly discovered. Such legitimacy was sanctified by the Pope Alexander VI in the Bull Inter Caetera of May 3, 1493, which recognized Spain’s sovereignty over all territories discovered after Christmas 1492 that were located West of an imaginary line drawn through the Atlantic Ocean from the Artic Pole to the Antarctic Pole (to be distant one hundred leagues towards the west and south from the Azores and Cape Verde), while granting Portugal sovereignty upon whatever it discovered in Africa.43 38. BROWNLIE, supra note 35, at 71. 39. See 1 CHARLES CHENEY HYDE, INTERNATIONAL LAW CHIEFLY AS INTERPRETED AND APPLIED BY THE UNITED STATES 16 (1922). 40. Western Sahara Advisory Opinion, 1975 I.C.J. 18, para. 80 (Oct. 17). 41. Id. para. 81. 42. Clinebell & Thomson, supra note 37, at 676-77. 43. “Among other works well pleasing to the Divine Majesty and cherished of our heart, this assuredly ranks highest, that in our times especially the Catholic faith and the Christian religion be exalted and be everywhere increased and spread, that the health of souls be cared for and that barbarous nations be overthrown and brought to the faith itself . . . [Y]ou [sic] purpose also, as is your duty, to lead the peoples dwelling in those islands and countries to embrace the Christian religion . . . [W]e . . . by the authority of Almighty God conferred upon us . . . give, grant, and assign forever to you and your heirs and successors, kings of Castile and Leon, forever, together with all their dominions, cities, camps, places, and villages, and all rights, jurisdictions, and appurtenances, all islands and mainlands found and to be found, discovered and to be discovered towards the west and south, by drawing and establishing a line from the Arctic pole, namely the north, to the Antarctic pole . . . .” The Bull Inter Caetera of 1493, available at http://www.dlncoalition.org/related_issues/inter_caetera.htm (English translation); see also Peter d’Errico, Inaugural Lecture in the American Indian Civics Project at Humboldt State University, American Indian Sovereignty: Now You See It, Now You Don’t (Oct. 24, 1997), available at http://www.nativeweb.org/pages/legal/sovereignty.html.

- 12. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 2006 SOVEREIGNTY REVISITED 165 The fiction of terra nullius continued to be applied for a number of centuries, until the end of the geographic discoveries, allowing the Europeans to colonize all the newly discovered worlds. The only significant exception, at least in principle, to such kind of practice was represented by the Treaty of Waitangi, which was signed on February 6, 1840, in New Zealand between the chiefs of the Confederation of the United Tribes of New Zealand and other Maori tribal leaders on one side and the British Crown on the other side.44 Although the correct interpretation of the Treaty has always been debated on account of the different meaning of the terms used in the English version and in the Maori translation, the main content of the treaty may be summarized as follows: the first article grants the Queen of the United Kingdom “governorship” (kawanatanga) over New Zealand, while, according to the second, the Maori chiefs retain rangatiratanga, which literally means “chieftainship,” but in the light of the concrete meaning assigned to it by the Maori it may also mean “absolute sovereignty,” “self-determination” or, to a certain extent, “independence.” 45 In any event, it embraces the spiritual link the Maori have with Papatuanuku (Earthmother or Mother Earth), and recognizes a certain degree of Maori sovereignty over their ancestral lands. Nowadays, the starting point of claims for indigenous sovereignty lies exactly in the fact that indigenous peoples were, at the relevant time, illegitimately deprived of the lands ancestrally occupied and governed by them as entities actually owning the attributes of sovereignty pursuant to international law. The original perception that such lands were to be considered as freely occupiable has in fact significantly changed in more recent times.46 The fact that, for example, Native American tribes were sovereign over their territories when they were subjugated by the Europeans was already recognized in the early nineteenth century by Chief Justice Marshall of the U.S. Supreme Court, in Johnson v. M’Intosh, by affirming that, at the time that it was discovered by Columbus, North America . . . was held, occupied, and possessed, in full sovereignty, by various independent tribes or nations of Indians, who were the sovereigns of their respective portions of the territory, and the absolute owners and proprietors of the soil; and who neither acknowledged nor owed any allegiance or obedience to any European sovereign or state whatever. 47 Today, the concept of “indigenous sovereignty” (i.e., “tribal sovereignty”) is generally meant as self-government (which may be considered as equivalent to “internal self-determination”), the extent of which varies in the different States but, in any event, would never be so wide as to override the supreme sovereign powers of the national government. In other words, any “sovereign” prerogative recognized to 44. Treaty of Waitangi (N.Z. 1840), available at http://www.treatyofwaitangi.govt.nz/treaty. 45. Salmon, John et al, Te Tino Rangatiratanga, presented to the Methodist Church Council (May 1990). 46. The actual possession of sovereign powers by the native tribes of the Americas was already recognized by the majority of scholars in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. See, e.g., Clinebell and Thomson, supra note 37, at 680-81. 47. Johnson v. M’Intosh, 21 U.S. (8 Wheat.) 543, 545 (1823); Larry Sager, Rediscovering America: Recognizing the Sovereignty of Native American Indian Nations, 76 U. DET. MERCY L. REV. 745, 746 (1999).

- 13. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 166 TEXAS INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL VOL. 42:155 indigenous peoples would always be subjected to the control of the territorial State, which may constantly limit or condition, pursuant to its own relevant constitutional or legislative rules, the effective exercise of such prerogatives. The notion of “indigenous sovereignty” is strictly linked to that of “aboriginal title,” which focuses on the ownership by indigenous peoples of the lands occupied by them before the arrival of foreign settlers. The latter concept is based on the assumption that when a colonizing power has acquired sovereignty over a land belonging to indigenous peoples, it would only mean that such power has gained the imperium (right to govern), but not the dominium (ownership right), over such land.48 Such dominion would be retained by the indigenous communities concerned unless “expressly extinguished by statute or by voluntary sale or cession.”49 The fact that the title in point may be extinguished by statute means that it may be unilaterally extinguished by the State. This observation may apparently be extended to indigenous sovereignty in general, in the sense that, up to the present, its effective enjoyment has been generally based on the determination of the government of the State in which the indigenous communities concerned are located, with the implication that the government could always withdraw any sovereign prerogative to those communities. The main purpose of the following sections is to ascertain whether this apparently unconditional freedom of national governments to determine the scope of indigenous sovereignty (inclusive of the power to absolutely deny any sovereign prerogative to indigenous peoples) is today limited by international law, on account of the most recent developments achieved by such law in the fields of human and peoples’ rights and of relevant State practice. In other words, does international law, and to what extent, support the legitimate aspiration of indigenous peoples “to choose what their future will be,” as indigenous sovereignty has been efficaciously summarized by a scholar?50 IV. MAJOR POTENTIAL TITLES OF INDIGENOUS SOVEREIGNTY In light of the identification of the elements of the concept of sovereignty and of the principles which may interfere with the determination of the extent of this concept, summarily made in the previous sections, it is now possible to try to ascertain what potential legal titles may be invoked for maintaining the existence of sovereignty rights belonging to indigenous peoples under international law. At a preliminary stage, it is necessary to emphasize that, according to the notion of sovereignty followed in the present work, sovereignty of indigenous peoples may only exist if, and to the extent that international law binds States, to grant them the exercise of certain sovereign powers that indigenous peoples themselves are in principle entitled to claim and possibly enforce, to whatever extent, at the international level. The degree of indigenous sovereignty corresponds to the scope that such sovereign powers, if existing, are protected by international 48. Cathy Marr, Robin Hodge & Ben White, Crown Laws, Policies, and Practices in Relation to Flora and Fauna, 1840 – 1912, at 69 (Waitangi Tribunal 2001), available at http://www.waitangi- tribunal.govt.nz/doclibrary/public/wai262/crownlawspolicies/Prelims.pdf. 49. Id. 50. See Robert B. Porter, The Meaning of Indigenous Nation Sovereignty, 34 ARIZ. ST. L.J. 75, 75 (2002).

- 14. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 2006 SOVEREIGNTY REVISITED 167 law, in that it prevents States from having the opportunity of legally interfering with their exercise, which is thus not subject to the decisional power of the territorial government. In other words, States would not be able to condition the autonomy, although limited, of indigenous peoples, by relying on their domestic law, and would thus be compelled to respect the degree of sovereignty granted to them by international law without interfering with its exercise. In the event, and to the extent that, it exists, such kind of sovereignty would be parallel to that held by the territorial State, in the sense that it could not invade the competences of the latter which, for its part, could not inhibit indigenous peoples from enjoying their sovereign powers as recognized by international law. A. Recognizing the Invalidity of the Original Title of Indigenous Lands Occupation and of the Native Title’s Legal Significance 1. The relevant practice The “original sin” which led to the “occupation” by foreign settlers of the ancestral lands of indigenous peoples lies, as previously emphasized, within the fiction of terra nullius. At the time of the discovery and occupation of those lands, the European colonizers claimed the legality of their conduct on the basis of the alleged fact that no legal organization existed which governed such territories. 51 As previously noted, this fiction was continued for a number of centuries, but in recent times its legality has been strongly challenged, and eventually, denied. At the international level, the invalidity of the principle of terra nullius has been proclaimed by the ICJ in its 1975 Advisory Opinion on the Western Sahara, stating that at the time of colonization by Spain the territory was not a land belonging to no one, since it “was inhabited by peoples which, if nomadic, were socially and politically organized in tribes and under chiefs competent to represent them.”52 It is indisputable that at the time of the European occupation of the lands ancestrally belonging to indigenous peoples virtually all these peoples were politically organized in the sense explained by the ICJ. A similar doctrine has been developed at the domestic level by most States where indigenous communities live. In the United States, for example, the original title of sovereignty of indigenous peoples has been recognized since the first half of the nineteenth century, with the historical findings of Chief Justice John Marshall of the United States Supreme Court.53 In the two historical cases Cherokee Nation v. Georgia and Worcester v. Georgia, Chief Justice Marshall introduced a narrative of the Indian tribes as nations, although “domestic dependent nations,” clearly denying that their traditional lands were nullius at the time of their occupation by the 51. On the fiction of terra nullius and other related concepts under an historical perspective, see S. JAMES ANAYA, INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN INTERNATIONAL LAW, 29-31 (2d ed. 2004). 52. Western Sahara Advisory Opinion, supra note 40, para. 81. In stating such a principle, the Court finally endorsed what had been maintained for centuries by the most eminent international law writers, including Francisco de Vitoria and Ugo Grotius. See T. W. Bennett & C.H. Powell, Aboriginal Title in South Africa Revisited, 15 S. AFR. J. HUM. RTS. 449, 455-56 (1999). 53. See Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. 1 (1831); see also Worcester v. Georgia, 31 U.S. 515 (1832).

- 15. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 168 TEXAS INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL VOL. 42:155 Europeans.54 In the words of Justice Marshall, those nations had been admitted by the U.S. Constitution “among those powers who are capable of making treaties . . . We have applied [the words ‘treaty’ and ‘nation’] to Indians, as we have applied them to the other nations of the earth. They are applied to all in the same sense.”55 From this sentence it appears the Indian nations had sovereign rights comparable to those owned by foreign States. Nevertheless, the fact that the native peoples were recognized as “domestic dependent nations” implied that they were permanently subordinated to Congress as a matter of American law and that, as the majority of the Court held, “an Indian tribe or nation within the United States is not a foreign state in the sense of the constitution, and cannot maintain an action in the courts of the United States.”56 In more recent times, the Supreme Court explicitly recognized that “[b]efore the coming of the Europeans, the tribes were self-governing sovereign political communities,”57 and their powers are, in principle, “inherent powers of a limited sovereignty which has never been extinguished,”58 although they are “no longer ‘possessed of the full attributes of sovereignty.’”59 Thus, in the words of the Supreme Court, [the] incorporation [of Indian tribes] within the territory of the United States, and their acceptance of its protection, necessarily divested them of some aspects of the sovereignty which they had previously exercised . . . . In sum, Indian tribes still possess those aspects of sovereignty not withdrawn by treaty or statute, or by implication as a necessary result of their dependent status.60 These findings have been ultimately confirmed in the recent case of United States v. Lara, when the Court defined the power of Indian tribes over their land and people as “inherent sovereignty.”61 According to Justice Stevens, this is based on the circumstance that such tribes “governed territory on this continent long before Columbus arrived.”62 But the Court was very careful in confirming that Congress has “plenary and exclusive powers over Indian affairs . . . .”63 In concrete terms, the sovereign prerogatives of Indian nations entail, “in addition to the power to punish tribal offenders, the . . . inherent power to determine tribal membership, to regulate domestic relations among members, and to prescribe rules of inheritance for members”;64 that is, the power of legislating with regard to the matters of tribal competence and the corresponding authority to enforce respect of the relevant rules within their jurisdictional limits, through the use of the means typical of any 54. Cherokee Nation, 30 U.S. at 17; Worcester, 31 U.S. at 559-60. 55. Worcester, 31 U.S. at 559-60. Justice Marshall found the theoretical foundation of indigenous sovereignty in the fact that “a weaker power does not surrender its independence—its right to self- government, by associating with a stronger, and taking its protection.” Id. at 561. 56. Cherokee Nation, 30 U.S. at 20. 57. United States v. Wheeler, 435 U.S. 313, 322-23 (1978). 58. Id. at 322 (quoting F. COHEN, HANDBOOK OF FEDERAL INDIAN LAW 122 (1945)). 59. Id. at 323 (quoting U.S. v. Kagama, 118 U.S. 375, 381 (1886)). 60. Id. 61. U.S. v. Lara, 541 U.S. 193, 210 (2004). 62. Id. 63. Washington v. Confederated Bands and Tribes of Yakima Nation, 439 U.S. 463, 470 (1979). 64. Montana v. United States, 450 U.S. 544, 564 (1981).

- 16. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 2006 SOVEREIGNTY REVISITED 169 governmental authority, including tribal courts (existing since 1883). Although such courts do not have full jurisdiction over non-Indians,65 they may exercise civil authority over non-members within tribal lands to the extent necessary to protect health, welfare, economic interests, or political integrity of the tribal nation.66 In addition, as stated by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1990, they “possess their traditional and undisputed power to exclude persons who they deem to be undesirable from tribal lands . . . . Where jurisdiction to try and punish an offender rests outside the tribe, tribal officers may exercise their power to detain and transport him to the proper authorities.”67 Similar developments have characterized the evolution of the legal recognition of the original title of indigenous sovereignty outside the United States. In Australia, the turning point which led to a break with the past was the landmark decision pronounced by the High Court in the 1992 case Mabo v. Queensland [No.2], when the Court debunked the fiction of terra nullius as historically invalid and not in accordance with modern standards of human rights and justice.68 The Court recognized the survival of common law Native Title, in co-existence with the radical (that is to say “sovereign,” or “plenary”) title of the British Crown, as implying the right of aboriginal peoples “as against the whole world to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of” any portion of the lands owned by them prior to the establishment of the British Colony of New South Wales in 1788, except in the case that such title has been legally extinguished.69 It is a title that, in any event, may be legally extinguished by the competent governmental authorities “by valid exercise of their respective powers.”70 The principle proclaimed by the Court has successively been taken in by national legislation, through the enactment of the Native Title Act of 199371 and, following another important decision of the High Court, Wik v. Queensland of 1996,72 the Native Title Amendment Act of 1998.73 Unfortunately, in drafting such legislation, the Australian Parliament devoted primary attention to a preoccupation with placating the interests of non-aboriginals on indigenous lands threatened by the Court’s recognition of the aboriginal title.74 Also, thanks to the fact that the High Court failed to address in concrete terms the issue concerning the specific titles on the land, which could lead to the extinction of the Native Title,75 the Australian Parliament recognized that, in the event of conflict between the Native 65. Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 435 U.S. 191, 212 (1978). 66. Montana, 450 U.S. at 566. 67. Duro v. Reina, 495 U.S. 676, 696-97 (1990). 68. Mabo v. Queensland [No.2] (1992) 175 C.L.R. 1, 40-42. 69. Id. at 2. 70. Id. 71. Native Title Act, 1993, pmbl. (Austl.), available at http://scaleplus.law.gov.au/html/pasteact/2/1142/pdf/NativeTitle1993.pdf. 72. Wik v. Queensland (1996) 187 C.L.R. 1, 6-9. 73. Native Title Amendment Act, 1998, sched. 1, available at http://scaleplus.law.gov.au/html/comact/10/5874/rtf/Act97of1998rtf. 74. Carlos Scott López, Reformulating Native Title in Mabo’s Wake: Aboriginal Sovereignty and Reconciliation in Post-Centenary Australia, 11 TULSA J. COMP. & INT’L L. 21, 37-38 (2003). On “aboriginal sovereignty” in Australia, see Otto, supra note 33, at 65. Gary D. Meyers & Sally Raine, Aboriginal Land Rights in Transition (Part II): The Legislative Response to the High Court's Native Title Decisions in Mabo v. Queensland and Wik v. Queensland, 9 TULSA J. COMP. & INT’L L. 95, 115 (2001). 75. López, supra note 74, at 34.

- 17. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 170 TEXAS INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL VOL. 42:155 Title and other titles granted by the Crown, the latter prevail.76 More recently, in the 2002 judgments of Ward (also known as Miriuwung Gajerrong)77 and Wilson,78 the High Court confirmed that the Native Title may be partially or totally extinguished by competing titles granted by the Crown, such as pastoral and mining leases.79 In Canada aboriginal rights, including the Native Title, have been recognized at the constitutional level since 1982, by the Constitution Act, stating that “[t]he existing Aboriginal and treaty rights of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognised and affirmed.”80 By virtue of this provision, all native rights existing at the time of the adoption of the constitutional amendment, whether derived from common law or treaty, are protected, while those that had been previously extinguished have no constitutional protection. This protection is not absolute, and may be overridden in the presence of certain conditions, which were defined by the Supreme Court in the 1990 judgment concerning the case of Sparrow v. The Queen.81 In particular, according to the Court, “[l]egislation that affects the exercise of aboriginal rights will be valid if it meets the test for justifying an interference with a right recognized and affirmed” under the 1982 Constitution Act.82 Thus, any legislative objective “must be attained in such a way as to uphold the honour of the Crown and be in keeping with the unique contemporary relationship, grounded in history and policy, between the Crown and Canada’s aboriginal peoples.”83 To meet this condition it is necessary that, first, a prima facie interference by the legislation enacted by the Crown giving rise to an adverse restriction of the exercise of the constitutionally protected natives’ rights is found;84 and, second, the interference must be justified.85 The “justification test” involves two steps: the existence of a valid legislative objective must be ascertained and, if such objective is found, “the special trust relationship and the responsibility of the government vis-à- vis aboriginal people” must be considered.86 That is, the legislative objective is to be balanced with the special trust relationship between the Crown and aboriginal peoples. In 1995, the Canadian Government explicitly recognized the inherent right of self-government of indigenous peoples, which is based on the view that the Aboriginal peoples of Canada have the right to govern themselves in relation to matters that are internal to their communities, integral to their unique cultures, identities, traditions, 76. Id. at 39. 77. W. Australia v. Ward (2002) 213 C.L.R. 1. 78. Wilson v. Anderson (2002) 213 C.L.R. 401. 79. López, supra note 74, at 44-45. 80. Part II of the Constitution Act, 1982, Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982, ch. 11, sec. 35(1) (U.K.), as reprinted in R.S.C., No. 44 (Appendix 1982), available at http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/const/annex_e.html. On the aboriginal title in Canada see Özlem Ülgen, Aboriginal Title in Canada: Recognition and Reconciliation, 47 NETH. INT’L L. REV. 146, 150-51 (2000). 81. Sparrow v. The Queen, [1990] 1 S.C.R. 1075. 82. Id. at 1077 (under Section 35(1) of the Constitution Act). 83. Id. at 1078. 84. See id. 85. Id. at 1079. 86. Id.

- 18. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 2006 SOVEREIGNTY REVISITED 171 languages and institutions, and with respect to their special relationship to their land and their resources.87 And while differing views exist, “the Government acknowledges that the inherent right of self-government may be enforceable through the courts.”88 The Supreme Court’s 1997 judgment concerning the case Delgamuukw v. British Columbia89 is also of great importance, representing a clear step forward, “in a more expansive and culturally sensitive way,”90 with respect to the jurisprudence of the High Court of Australia concerning the Native Title. In particular, the Court emphasized that the aboriginal title “encompasses the right to exclusive use and occupation of land.”91 The “content of aboriginal title is not restricted to those uses which are elements of a practice, custom or tradition integral to the distinctive culture of the aboriginal group claiming the right,”92 but also incorporates modern uses of the land, including mineral rights and the exploitation of minerals.93 In addition, the Court considered the aboriginal title as inalienable, affirming that it “cannot be transferred, sold or surrendered to anyone other than the Crown and, as a result, is inalienable to third parties.”94 Also, the Court placed emphasis on the opportunity to resolve disputes involving conflicting interests connected to the aboriginal title through recourse to negotiations, by recalling what it had previously said in Sparrow v. The Queen, that section 35(1) of the 1982 Constitution Act “provides a solid constitutional base upon which subsequent negotiations can take place.”95 In this context, “the Crown is under a moral, if not a legal, duty to enter into and conduct those negotiations in good faith.”96 Finally, with respect to the decisions taken by the Crown concerning aboriginal lands, the involvement of aboriginal peoples is always to be ensured. This implies: There is always a duty of consultation . . . . The nature and scope of the duty of consultation will vary with the circumstances. In occasional cases, when the breach is less serious or relatively minor, it will be no more than a duty to discuss important decisions that will be taken with respect to 87. See MINISTRY OF INDIAN AFFAIRS AND NORTHERN DEVELOPMENT, ABORIGINAL SELF- GOVERNMENT: THE GOVERNMENT OF CANADA’S APPROACH TO IMPLEMENTATION OF THE INHERENT RIGHT AND THE NEGOTIATION OF ABORIGINAL SELF-GOVERNMENT 5 (Ronald A. Irwin ed., Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 1995), available at http://www.iigr.ca/pdf/documents/1227_Aboriginal_SelfGovernme.pdf. 88. Id. 89. Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, [1997] S.C.R. 1010. 90. LARISSA BEHRENDT, PARLIAMENT OF AUSTRALIA LAW AND BILLS DIGEST GROUP, THE PROTECTION OF INDIGENOUS RIGHTS: CONTEMPORARY CANADIAN COMPARISONS, RESEARCH PAPER 27 (2000), available at http://www.aph.gov.au/library/pubs/rp/1999-2000/2000rp27.htm#aboriginal. 91. Delgamuukw, [1997] S.C.R. at 1111. 92. Id. at 1087-88; see also R. v. Van der Peet, [1996] 2 S.C.R. 507, 579 (the aboriginal title “refers to a broader notion of aboriginal rights arising out of the historic occupation and use of native ancestral lands, which relate not only to aboriginal title, but also to the component elements of this larger right—such as aboriginal rights to hunt, fish or trap, and their accompanying practices, traditions and customs—as well as to other matters, not related to land, that form part of a distinctive aboriginal culture.”). 93. See Delgamuukw, [1997] S.C.R. at 1086. 94. Id. at 1081. 95. Id. at 1123 (quoting Sparrow v. The Queen, [1990] S.C.R. 1075, 1105). 96. Id.

- 19. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 172 TEXAS INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL VOL. 42:155 lands held pursuant to aboriginal title. Of course, even in these rare cases when the minimum acceptable standard is consultation, this consultation must be in good faith, and with the intention of substantially addressing the concerns of the aboriginal peoples whose lands are at issue. In most cases, it will be significantly deeper than mere consultation. Some cases may even require the full consent of an aboriginal nation, particularly when provinces enact hunting and fishing regulations in relation to aboriginal lands.97 With regard to the African continent, a recent judgment of the Constitutional Court of South Africa, concerning the Richtersveld indigenous community, is worth mentioning.98 In this dispute, the community (belonging to family of the San people) claimed restitution of its ancestral land, of which it had been progressively deprived by the South African government from 1926 onwards (the “expropriation” was completed in 1993) after the discovery of diamonds in its subsurface. The claim was based on section 2(1) of Land Rights Act (Act 22 of 1994), which, in giving effectiveness to section 25(7) of the South African Constitution of 1996, states that a community dispossessed of its own land after June 19, 1913 (the date in which the Natives Land Act 27 of 1913, which deprived black South Africans of the right to own lands and rights in the land in the great majority of South African territory, came into operation), as a result of past racially discriminatory laws or practices is “entitled to restitution of a right in land.”99 In dealing with this case, the Court preliminarily ascertained whether the Richtersveld Community could be considered as owning the subject land prior to the annexation of the relevant territory by the British Crown, which took place in 1847.100 The Court held that, at the relevant time, the “land was communally owned by the community” concerned.101 This conclusion was reached on the basis of indigenous law, i.e., “the law which governed [the] land rights” of the Richtersveld Community at the relevant time,102 which is to be evaluated in light of the social and philosophical vision and criteria proper of the community, without making the error of “view[ing] indigenous law through the prism of legal conceptions that are foreign to it,”103 and particularly, “without importing English conceptions of property law.”104 Under indigenous law, indigenous land rights included “communal ownership of the minerals and precious stones,”105 as demonstrated by the fact that the Richtersveld Community commonly used minerals for adornment purposes, that “outsiders were not entitled to prospect for or extract minerals . . . [and] that the Richtersveld Community granted mineral leases to outsiders between the years 1856 and 1910.”106 In light of this, and after having ascertained that the 1847 annexation of the territory, in which the subject land was located, by the British Crown did not imply the extinguishment of the 97. Id. at 1113. 98. See Alexkor Ltd. & Another v. Richtersveld Cmty. & Others, 2003 (5) SA 460 (CC) (S. Afr.), available at http://www.constitutionalcourt.org.za/Archimages/758.PDF. 99. Id. para. 6 (quoting Land Rights Act). 100. Id. para. 32. 101. Id. para. 58. 102. Id. para. 50. 103. Id. para. 54. 104. Alexkor, 2003 (5) SA para. 50. 105. Id. para. 64. 106. Id. para. 61.

- 20. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 2006 SOVEREIGNTY REVISITED 173 indigenous title over such land, the Court went on to consider whether, pursuant to section 2(1) of the Land Rights Act, the dispossession of the rights of the Richtersveld Community taking place after 1913 was the result of racially discriminatory laws or practices.107 The conclusion was that, “given that indigenous law ownership is the way in which black communities have held land in South Africa since time immemorial,” the “inevitable impact” of the dispossession of land rights belonging to the Richtersveld Community, in that it entailed the “failure to recognise indigenous law ownership,” and “was racially discriminatory against black people who were indigenous law owners.”108 In other words, according to the Court, “the racial discrimination lay in the failure to recognize and accord protection to indigenous law ownership while, on the other hand, according protection to registered title[s]” of white diamond exploiters.109 The Court thus declared that the Richtersveld Community was entitled to “restitution of the right to ownership of the subject land (including its minerals and precious stones) and to the exclusive beneficial use and occupation thereof.”110 The practice referred to in the present paragraph is not limited to a restricted group of States, since most countries in whose territories indigenous peoples are living have surrendered to the duty of recognizing a given degree of autonomy (i.e., sovereignty) in favor of such peoples. This has happened, for instance, in Norway,111 where, since 1971, significant legislative112 and judicial steps have eventually led to the approval, in 1988, of the new article 110(a) of the Constitution, affirming that “it is the responsibility of the authorities of the State to create conditions enabling the Sami people to preserve and develop its language, culture and way of life.”113 In New Zealand, the Treaty of Waitangi Act of 1975 finally gave effectiveness to the treaty signed in 1840 by the British Crown with the Maori chiefs, by instituting the Waitangi Tribunal and regulating disputes concerning the land and related rights between indigenous and European-originated people according to a scheme not dissimilar to that of intergovernmental negotiations.114 Also, in 1993, the Constitutional Court of Colombia recognized that the exploitation of natural resources in indigenous lands raised a constitutional problem which involved the ethnic, cultural, social, and economic integrity of the communities that live therein.115 Last but not least, in recent years, Malaysian courts have recognized, the indigenous right of ownership of their ancestral land based on customary law, although such 107. Id. para. 69, 82. 108. Id. para. 96. 109. Id. para. 99. 110. Alexkor, 2003 (5) SA para. 103. 111. With regard to North European countries, see Lauri Hannikainen, The Status of Minorities, Indigenous Peoples, and Immigrant and Refugee Groups in Four Nordic States, 65 NORD. J. INT’L L. 1 (1996). 112. See Lov om reindrift [Reindriftsloven] [Reindeer Herding Act] (Norges lover 1978:49) (Nor.); Lov om Sametinget og andre samiske rettsforhold [Sameloven] [Sami Act] (Norges lover 1987:56) (Nor.). 113. Norges grunnlov [Constitution] art. 110a (Nor.). 114. See López, supra note 74, at 74. 115. See Sentencia No. T-380/93, para. 7 (1993) (“La explotación de recursos naturales en territorios indígenas plantea un problema constitucional que involucra la integridad étnica, cultural, social y económica de las comunidades que sobre ellas se asientan.”), available at http://bib.minjusticia.gov.co/jurisprudencia/CorteConstitucional/1993/Tutela/T-380-93.htm.

- 21. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 174 TEXAS INTERNATIONAL LAW JOURNAL VOL. 42:155 right may be terminated by the government, which retains the power to acquire the lands concerned through the payment of adequate compensation.116 2. The inadequacy of the recognition of the invalidity of the title of terra nullius and of the legal significance of the Native Title, ex se, as foundation of indigenous sovereignty Having ascertained the existence of a widespread practice, both at the international and (especially) domestic level, that recognizes the original invalidity of the title of occupation (based on the invention of the concept of terra nullius) of the lands originally belonging to indigenous communities, the question which arises concerns the relevance of such recognition in the framework of international law. In other words, is such recognition capable of producing significant consequences at the international level, thus creating some kind of foundation for indigenous claims of sovereignty and corresponding State obligations? A pragmatic and objective assessment of the whole matter shows quite clearly that the answer to the question, in purely legal terms, is negative. According to international law, sovereignty is linked to the effective control of a territory, and when this effectiveness exists (accompanied by effective independence) it normally amounts to sovereignty, irrespective of the way in which this control has been attained. Relevant practice demonstrates that, also in recent history, the fact that a territory has been acquired by using unlawful means has never constituted an obstacle to the effective acquisition of sovereignty over the territory, except in specific cases, essentially linked to the movement for decolonization. In the contemporary international legal regime, the existing division of sovereignty among States is well-crystallized, and the principle of (external) self-determination of peoples may only attract (with the exception of colonial peoples) new situations generated after the end of World War II.117 It is thus not applicable to the occupation of the lands of indigenous peoples. It is true that the express denial of the relevance of the original title of terra nullius resulting from the practice illustrated in the preceding paragraph has an indisputable moral significance, which may result in a strong pressure over States aimed at persuading them to recognize a given degree of autonomy in favor of indigenous peoples. Nevertheless, in strictly legal terms, the choice whether such autonomy is to be granted or not, if considered solely under the perspective examined in the present paragraph, lies in the free determination of the sovereign territorial State. Logically speaking, this conclusion could appear to change when considering the whole matter from the perspective of decolonization, based on the principle of self-determination of peoples. The fact that most indigenous peoples, as peoples 116. See Federico Lenzerini, The Interplay Between Environmental Protection and Human and People’s Rights in International Law, 10 AFR. Y.B. INT’L L. 63, 105 (2002); Botswana bushmen win land ruling, BBC NEWS, Dec. 13, 2006, available at http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/africa/6174709.stm; see also the very recent judgment (13 December 2006) of the High Court of Lobatse, Botswana, which held that the national government had acted illegally in forcibly evicting the last tribal Bushmen (also known as the Basarwa) from the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, in 2002, in order to exploit the diamond and mineral resources located in that area. Consequently, the Court found that the Basarwa are entitled to live and hunt on their ancestral lands in the Reserve. 117. See BENEDETTO CONFORTI, DIRITTO INTERNAZIONALE 22 (Napoli 2006).

- 22. 09 Lenzerini Publication 3/29/2007 1:43:55 PM 2006 SOVEREIGNTY REVISITED 175 originally subject to alien domination, would factually meet the legal requirements for having access to self-determination (in the meaning of the term which led to decolonization) is logically undeniable on the basis of the ICJ’s decision in the Western Sahara case118 and of the 1960 Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples;119 in addition, the fact that the rejection of the legal fiction of terra nullius, both at the international and domestic level, implies the acknowledgement of the prior occupation by indigenous peoples of their ancestral lands. Nevertheless, the fact remains that the content of international law is determined only by States, which may establish, through their consistent practice and mental behaviour (i.e., opinio juris), whether a given rule exists or not, often at the prejudice of legal coherence. This circumstance was recalled by the U.S. Court of Appeals in the recent judgment United States v. Yousef, when the Court stated that, for determining the content of international law, one must primarily consider “the formal lawmaking and official actions of States and only secondarily . . . the works of scholars as evidence of the established practice of States.”120 With this incontestable dogma in mind, prior consideration is to be attributed to the fact that States have always strongly opposed (and continue to oppose) the recognition of the right to self-determination, conceived in its external connotation, in favor of indigenous peoples. This is demonstrated, in particular, by the very first article of the only binding international instrument in force at the universal level specifically dealing with such peoples, the 1989 ILO Convention No. 169 Concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries, which makes it clear that “[t]he use of the term ‘peoples’ in this Convention shall not be construed as having any implications as regards the rights which may attach to the term under international law.”121 In addition, it is a fact that most States, although recognizing a limited degree of indigenous sovereignty, consider such sovereignty as subordinated to the circumstance that the territorial government does not exercise its right to extinguish the aboriginal title within the context of the exercise of its sovereign power over the national territory. Most of the aforementioned judgments have been based on acts, laws, or statutes enacted by the States concerned that, as they have been adopted, in principle, may always be abrogated. Furthermore, in some countries, like Australia, the Native Title, although recognized in principle, is very precarious in practice, and may be easily extinguished by granting alternative titles over the land to non- aboriginals. Consequently, the recognition of such title at the domestic level, within the restricted terms just noted, may not, on its own, be considered as an argument capable of granting indigenous peoples the chance to claim and enforce their sovereign rights under international law against the “plenary” sovereign title of the territorial State. However, the most recent developments concerning the matter at issue could support the inference that this conclusion should be subject to change. In particular, twelve years after its approval by the Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights (formerly “Sub-Commission on Prevention of 118. See supra note 40 and corresponding text. 119. G.A. Res. 1514, at 66, U.N. GAOR, 15th Sess., Supp. No. 16, U.N. Doc. A/4494 (Dec. 14, 1960). 120. United States v. Yousef, 327 F.3d 56, 103 (2d Cir. 2003). 121. Int’l Labour Org. [ILO], Convention (No. 169) Concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries (Sept. 5, 1991) [hereinafter ILO Convention (No. 169)] (adopted by the General Conference of the International Labour Organisation on June 27, 1989, in force beginning September 5, 1991), available at http://www.ilo.org/ilolex/english/convdisp1.htm.