This document provides an overview and editorial for The Indigenous World 2010 publication. It summarizes some of the key developments and issues impacting indigenous peoples in 2009, as reported in the publication's country reports. These include Greenland gaining greater autonomy from Denmark and Bolivia approving a new constitution recognizing indigenous rights. However, it also notes ongoing threats to indigenous lands, rights, and cultures from large-scale development projects, climate change impacts, criminalization of protests, and failure to implement laws protecting indigenous peoples. The editorial frames these as ongoing struggles between indigenous self-determination and development aggression. It highlights the importance of mechanisms like the UNDRIP and ILO 169 in advocating for indigenous rights.

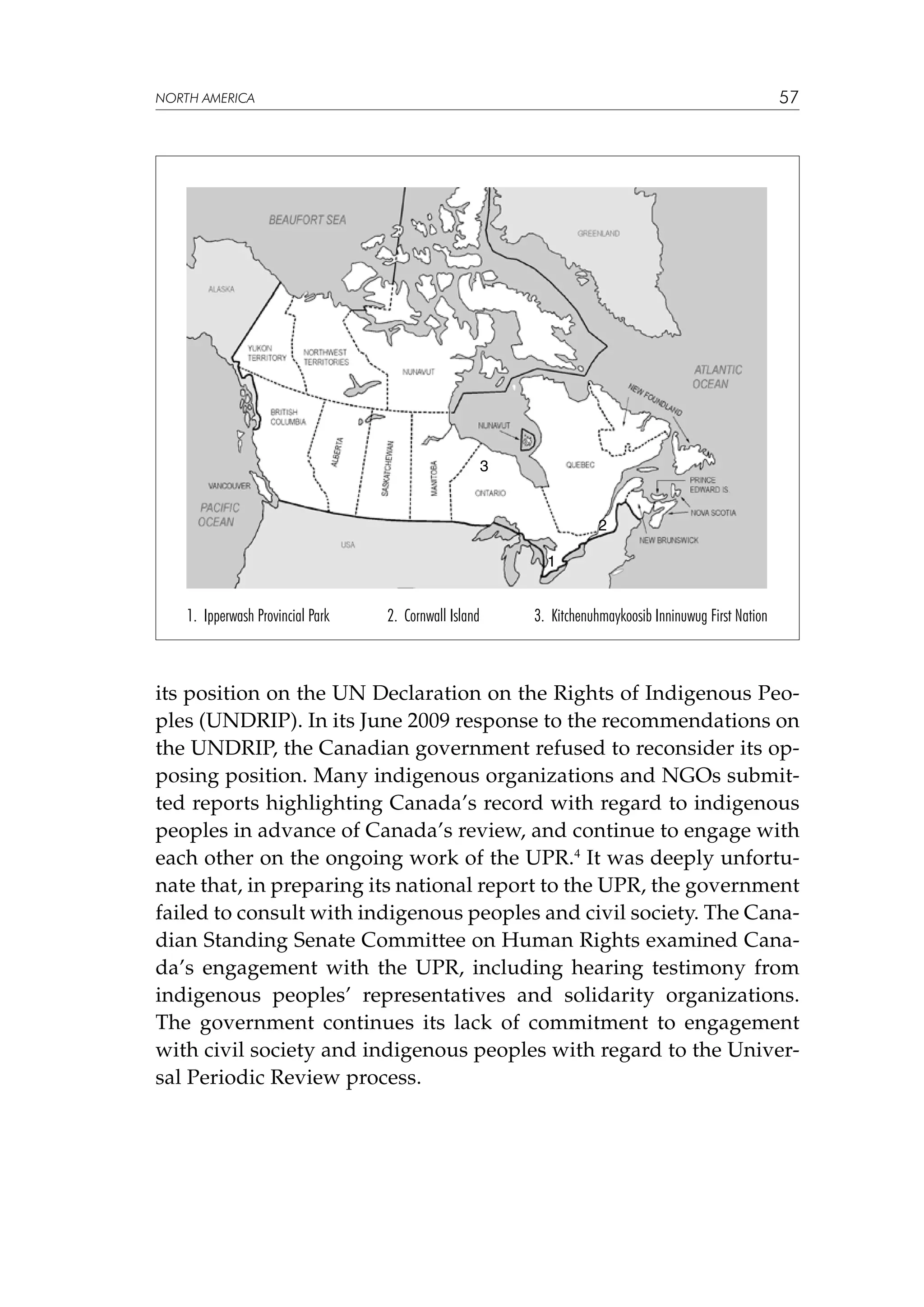

![NORTH AMERICA

65

fought for 11 years to stop Platinex from drilling for platinum on its

traditional lands. KI chief Donny Morris and five other community

members were sentenced to six months in jail last year for civil contempt of court after disobeying a court order to allow Platinex to explore on their territory. The Ontario Minister of Northern Development, Mines and Forestry, said that the government had responded to

the community’s concerns by withdrawing lands at Big Trout Lake

from mineral exploration.

Donny Morris has said he went to jail because his community

wanted the government to adhere to numerous Supreme Court of

Canada decisions affirming the duty to consult over development on

Aboriginal lands. The Ontario government has now also reformed the

province’s mining laws. The amended law now includes consultation

requirements but does not clarify the specific procedures to be followed by government and industry. The amendments also fail to require free, prior and informed consent. In the Haida Nation case, Canada’s highest court has ruled that the nature and scope of the Crown’s

duty to consult would require the “full consent of [the] aboriginal na

tion …on very serious issues”.17

Notes and references

1

2

3

4

5

Statistics Canada. 2009. Aboriginal Peoples of Canada: 2006 Census. Released 29

January 2009.

http://www.statcan.gc.ca/bsolc/olc-cel/olc-cel?lang=eng&catno=92-593-X

The Indian Act remains the principal vehicle for the exercise of federal jurisdiction over «status Indians», and governs most aspects of their lives. It defines

who is an Indian and regulates band membership and government, taxation,

lands and resources, money management, wills and estates, and education.

Hurley, Mary C., 1999: The Indian Act. http://dsp-psd.pwgsc.gc.ca/CollectionR/LoPBdP/EB/prb9923-e.htm

Human Rights Council. 2009, Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review: Canada, UN Doc. A/HRC/11/17 (3 Mar. 2009).

See, e.g., Grand Council of the Crees (Eeyou Istchee) et al 2008, Joint Submission to the United Nations Human Rights Council in regard to the Universal Periodic

Review Concerning Canada (Sept. 2008): http://lib.ohchr.org/HRBodies/UPR/

Documents/Session4/CA/JS4_EI_CAN_UPR_S4_2009_GrandCounciloftheCreesEeyouIstchee_Etal_JOINT.pdf.

This report and the accompanying release can be found at http://www.cfsc.

quaker.ca/pages/un.html.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0001i2010eb-140101004315-phpapp01/75/0001-i-_2010_eb-64-2048.jpg)

![66

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

IWGIA - THE INDIGENOUS WORLD - 2010

Jeffrey Simpson, “Canada and climate change: Nothing gets done, fingers get

pointed”, Globe and Mail (2 October 2009).

United Nations Environment Programme (Catherine P. McMullen and Jason

Jabbour (eds.)), Climate Change Science Compendium (Nairobi: EarthPrint,

2009) at ii (Forward by UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon).

Kathryn Tucker, “Ottawa flouts its legal obligations in tar sands development”,

The CCPA Monitor, Economic, Social and Environmental Perspectives, Canadian

Centre for Policy Alternatives, Vol. 16, No. 8, February 2010 at 22.

Human Rights Council. 2009. Report of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on the relationship between climate change and human

rights, UN Doc. A/HRC/10/61 (15 January 2009), para. 53.

Amnesty International Canada. 2009. Critical Human Right Tribunal hearings begin today. September 14, 2009. http://www.amnesty.ca/blog2.php?blog=hr_indigenous_peoples&month=9&year=2009.

The First Nations Child and Family Caring Society of Canada. 2009. I am a

Witness. December 31, 2009 http://www.fnwitness.ca/.

Native Women’s Association of Canada. 2009. Voices of Our Sisters In Spirit: A

Report to Families and Communities, (2d ed., 2009):

www.nwac-hq.org/en/documents/NWAC_VoicesofOurSistersInSpiritII_

March2009FINAL.pdf

Amnesty International. 2009. No More Stolen Sisters: The Need for a Comprehensive Response to Discrimination and Violence against Indigenous Women in Canada

(2009): www.amnesty.ca/amnestynews/upload/AMR200122009.pdf

See McIvor’s response to the government proposal. “Sharon McIvor’s Response

to the August 2009 Proposal of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada to Amend

the 1985 Indian Act”. October 6, 2009 http://www.nwac-hq.org/en/documents/SharonMcIvorResponsetoINACProposal.pdf and the Quebec Native

Women’s response: “Quebec Native Women’s Memoir on the McIvor Case” November 13, 2009 at http://www.faq-qnw.org/news.html

See, e.g. “QNW is concerned by the lack of consultation of Aboriginal peoples

from the government on the McIvor case.” At http://www.faq-qnw.org/news.

html

http://www.trc-cvr.ca/about.html

Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), [2004] 3 S.C.R. 511, para.

24.

Jennifer Preston is the Programme Coordinator for Aboriginal Affairs for

Canadian Friends Service Committee (Quakers). Her work focuses on international and domestic strategies relating to indigenous peoples’ human rights.

This includes the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous

Peoples. In this context, she has worked closely with indigenous and state

representatives as well as human rights organizations in various regions of

the world.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0001i2010eb-140101004315-phpapp01/75/0001-i-_2010_eb-65-2048.jpg)

![142

IWGIA - THE INDIGENOUS WORLD - 2010

sons for hope. In the judicial branch “there are judges, magistrates and

staff […] who behave like true officials, respectful of the law and who

sometimes even heroically protect the law”.19 A substantial proportion

of the Constitutional Court’s case law20 and the actions of the Supreme

Court of Justice against paramilitarism and its state supporters are a

considerable indication of this.

In its Ruling 004 of 2009, the Constitutional Court noted that the

indigenous peoples were suffering from “alarming patterns of forced

displacement, murder, lack of food and other serious problems because of the country’s armed conflict and other underlying factors”,

giving rise to urgent situations that had received no corresponding

state response. As a result, the Constitutional Court indicated that

many indigenous peoples across the country were being threatened

“with cultural and physical extinction” and called on the state to provide an integral and effective response to the pressures that were bearing down on both the indigenous and the Afro-Colombian peoples

(Ruling 005 called for a similar response for these latter).

It is not only the Constitutional Court that has stood up for this

broken country. The Supreme Court of Justice has also taken an exemplary role in defending the rule of law, forming the only obstacle to a

state takeover by narco-para-politics. The determination of these judges

to tackle the “white collar” crime that is rife within the state apparatus

has been exemplary, with a good part of the country’s political class

being brought to justice for drugs crimes and paramilitarism (as of

September 2009, 53 Congressmen or women had arrest warrants issued against them). Initially, these Congressmen were going to be tried

for “conspiracy to commit a crime” but, in a complex jurisprudential

twist on the part of the Supreme Court, the “para-politicians will no

longer be charged with conspiracy but with ‘crimes against humanity’

because they were involved in a political project that involved the use

of force to commit atrocities. This relates to an explicit military strategy, with armies supported by social and territorial power bases, to promote a project to “reshape the nation”21 and legalise the interests of

these illegal powers, in alliance with the so-called “legal powers” of

cattle ranchers, palm oil growers, environmental resource extractors,

etc.22](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0001i2010eb-140101004315-phpapp01/75/0001-i-_2010_eb-141-2048.jpg)

![SOUTH AMERICA

143

Other judges in the country took similar action to avoid the AfroColombian peoples from being dispossessed of their lands. On 5 October 2009, for example, the Chocó Administrative Court ordered nine

palm oil companies, two cattle ranches and 24 people to immediately

return land that had been taken by violent means to the black communities of Curvaradó and Jiguamiandó.23

Visit of the UN Special Rapporteur

In his visit to Colombia in July, James Anaya, the UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of

indigenous people, described “the human rights situation of the indigenous peoples as serious, critical and deeply concerning”, just as the

previous Special Rapporteur, Rodolfo Stavenhagen, had also noted

during his visit in 2004. The testimonies heard by the Special Rapporteur from various indigenous representatives with regard to the effects

of the armed conflict confirmed the Constitutional Court’s appraisal in

its Ruling 004.

It was only to be expected, given that almost 20 years on from ratifying ILO Convention 169, the violence against indigenous peoples

has not diminished in the country. According to data from ONIC, between 2002 and 2009 1,032 indigenous people were murdered in the

country. In the year 2009, up to the end of November, 76 murders had

been recorded. One of the indigenous peoples most affected is the

Awa, who lost 35 people over the course of 2009, 11 of whom, including children, were murdered at knifepoint by the FARC. The Awa state

that this was retaliation on the part of the FARC, which believed that

soldiers from the national army were sheltering in the houses of the

indigenous people, and that indigenous people were collaborating

with them. These people are suffering a process of ethnocide because,

“The terror they suffer…and the military pressures, external territorial

control, political conditioning and economic pressures to which their

communities are being subjected […] prevent them from designing a

life plan or successfully managing their future...”24

In relation to the armed conflict, the Special Rapporteur indicated

in his report that, according to the information received from the indig-](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0001i2010eb-140101004315-phpapp01/75/0001-i-_2010_eb-142-2048.jpg)

![146

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

IWGIA - THE INDIGENOUS WORLD - 2010

ignored by the different programmes planned by the government…” http://realidades.lacoctelera.net/

bogota.usembassy.gov/.../wwwfseriehouston2007alejandroreyes.pdf

Nuevo Arco Iris Corporation: Informe 2009 ¿El declive de la Seguridad Democrática? http://www.nuevoarcoiris.org.co/sac/?q=node/605

Colombia: the case of the Naya. IWGIA Report No. 2. 2008, Copenhagen-Bogota.

Moderation in the use of resources and their opposition to waste and destruction is condemned by President Uribe as “running counter to national development and progress”.

Revista Cambio: “Programa Agro Ingreso Seguro ha beneficiado a hijos de políticos y reinas de belleza”. http://www.cambio.com.co/paiscambio/847/ARTICULO-WEB-NOTA_INTERIOR_CAMBIO-6185730.html

Mondragón, Héctor: “The idea of a leadership convinced of a community of

interests between landowners, state, businessmen, peasant farmers, workers

[…] was extensively implemented by the “new” Fascist Italy of Mussolini. […]

a state organisation was promoted with decision-making power over policies,

programmes and budgets and which involved everyone around the interests of

large landowners, disguised as “national interests”. http://colombia.indymedia.org/news/2009/10/108419.php

This is the term used to denote the extrajudicial murder of unemployed youth

by members of the security forces, who were deceived with promises of work.

They were later presented as fallen guerrilla combatants. The aim of these fateful events was to achieve promotion, obtain licences and gain rewards. www.

dhcolombia.info/spip.php?article434

Giving of gifts with the aim of winning Congress’s approval of constitutional

changes aimed at a possible re-election of the President. www.elespectador.

com/tags/yidispolítica

The most well-known case was that of the President’s children, who through

their influence achieved a change in land use (from agricultural to commercial)

in order to establish free trade zones, thus increasing the value of the land onehundred-fold from what they had paid three months earlier. www.eltiempo.

com/archivo/.../MAM-3408439

The negligence and reluctance to seek the return of lands to those displaced by

violence. www.elperiodico.com.co/seccion.php?codigo=0

The victims’ law, by which it was sought to compensate the victims of violence,

was rejected by the Senate, following President Uribe’s decision not to support

it. www.cinep.org.co/node/708

Government opposition to signing a “humanitarian agreement” (“we don’t negotiation with terrorists”) to free those kidnapped (including members of the

security forces) and who have been held by the guerrilla for 10 years or more.

The level of “open” unemployment (which excludes under-employment and

informal sector work) is the highest the country has ever known and also the

highest in Latin America. www.banrep.gov.co/docum/ftp/borra176.pdf

http://www.senado.gov.co/portalsenado/index.php?option=com_

content&view=article&id=1014](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0001i2010eb-140101004315-phpapp01/75/0001-i-_2010_eb-145-2048.jpg)

![228

5

6

7

8

9

IWGIA - THE INDIGENOUS WORLD - 2010

Cf. Document from the “First meeting of indigenous peoples from AMA urban

territories” [AMA – Metropolitan Area of Asunción], National Secretariat for

Childhood and Adolescence, 11 October 2009.

Cf. Report presented by the Sawhoyamaxa to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights during the oversight hearing for the ruling, held in La Paz (Bolivia),

15 July 2009.

Cf. Journal of sessions of the Chamber of Senators, Ordinary session of 15 October 2009.

Cf. Report from the Centre for Study and Research into Rural Law and Agrarian

Reform (Ceidra), made public on 24 July 2009.

Article 64. “On community ownership their removal or transfer from their habitat without their express consent is prohibited”.

Oscar Ayala Amarilla is a lawyer and the executive coordinator of the human

rights NGO Tierraviva a los Pueblos Indígenas del Chaco. Over the last

15 years, he has devoted his time to litigation and research into the human

rights of indigenous peoples.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0001i2010eb-140101004315-phpapp01/75/0001-i-_2010_eb-227-2048.jpg)

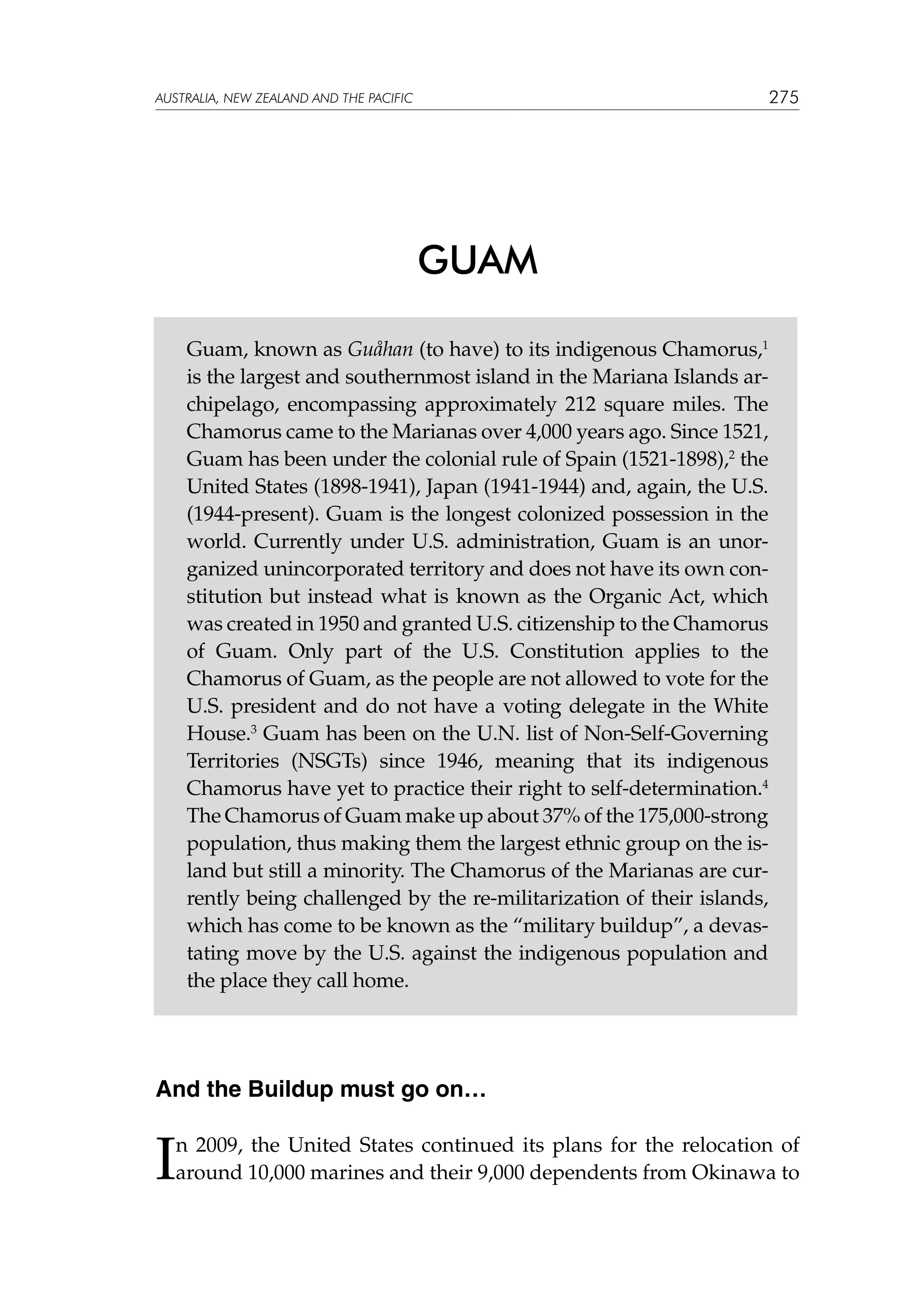

![278

IWGIA - THE INDIGENOUS WORLD - 2010

Fishing rights

The indigenous fishing rights bill was also a major issue in 2009. The

bill, initially known as Bill 327 and now known as Bill 190, was proposed by Senators Judith Guthertz and Rory Respicio and would allow for the Guam Department of Agriculture (DOA) to create programs and regulations that would recognize Chamoru fishing rights

and practices. It also proposes that indigenous Chamorus should be

able to fish off-shore and harvest ocean resources through the creation

of a Guam Aquatic Resources Council, composed of six indigenous

Chamorus from six Chamoru grassroots organizations. However,

while the bill calls for Chamoru fishing rights and practices to be recognized, it does not necessarily allow for fishing in Guam’s aquatic

preserves, though many people have interpreted the bill as allowing

such action.12 The Chamoru proponents of the bill have stated that they

“do not fish for profit but to put food on the table” and that they do not

overfish because they know the appropriate places and times to fish.

To the Chamorus, who have always been fishermen, fishing is moreover a cultural practice that allows them to connect with their past and

the people they come from. However, opponents to the bill have argued that it is discriminatory to non-Chamorus and could harm

Guam’s aquatic preserves. Yet according to Article 11 of the U.N. Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (which the U.S. continues

to fail to recognize), “Indigenous peoples have the right to practise and

revitalize their cultural traditions and customs. This includes the right

to maintain, protect, and develop the past, present, and future manifestations of their cultures [….].” The preliminary hearing for the bill

was held in August. The final hearing and decision-making have yet to

take place.

Notes and references

1

The Chamorus are the indigenous people of the Marianas Islands. Chamoru

also refers to the indigenous culture and language of the Marianas. In the early

1990s, there was debate over the spelling of Chamoru. The various spellings of

Chamoru included the following: Chamoru, Chamorro, and CHamoru. The author chooses to use “Chamoru”.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0001i2010eb-140101004315-phpapp01/75/0001-i-_2010_eb-277-2048.jpg)

![EAST SOUTH EAST ASIA

345

measures to promote the

perception

that

the

Orang Asli were being

well cared for by the

government. To this end,

a series of paid advertorials were placed in the

mainstream newspapers

informing the general

public of the amounts of

money that had been allocated for the upliftment of the Orang Asli,

and of the various programmes aimed at encouraging them to accept

modernity.

The public relations

campaign was also levelled at the United Nations. In response to concerns raised by the indigenous peoples of Malaysia via the Human

Rights Council’s Universal Periodic Review of

Malaysia, the Malaysian

Permanent Mission informed the General Assembly that “…ensuring

the protection of the

rights and the development of our indigenous

populations has always

been a national priority,

[and that] … the status

of indigenous people in](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0001i2010eb-140101004315-phpapp01/75/0001-i-_2010_eb-344-2048.jpg)

![354

IWGIA - THE INDIGENOUS WORLD - 2010

sentenced on the explicit charge of “causing global warming”. Two

cases are worthy of note:

Between February and April 2008, forestry officials arrested Mr. Dipaepho and Mrs. Nawhemui, both from the Karen indigenous people,

as they were preparing their fields for planting chillies and upland

rice. The charges against them relate to clearing of land, felling trees

and burning the forest within a national forest. This was considered as

contributing to the degradation of national forest land, damaging a

water source without permission and causing a rise in temperature.

Mr. Dipaepho was charged with damaging 21 rai and 89 wah (8.2

acres] of land at a value of 3,181,500 baht (US$91,000). Mrs. Nawhemui

was charged with damaging 13 rai and 8 wah (5.2 acres) of land at a

value of 1,963,500 baht (US$56,000). Both have been sentenced to pay

full compensation for these “damages”. The court further ordered that

Mr. Dipaepho be sent to prison for two years and six months but, as he

had confessed to the so-called “crime”, this was reduced to one year

and three months. Mrs. Nawhemui was also sentenced to two years in

prison, which was later reduced to one year after she also confessed to

the so-called “crime”.

Both of them had been released on bail, which was guaranteed by

the Local Administration Unit members from Maewaluang Sub-district. Both of them petitioned the Appeal Court. The Appeal Court

ruled that the case had not followed proper court procedure, as the

defendant claimed, and has therefore ordered the reopening of the

case. It is now ongoing and NIPT is concerned that it will set a precedent for future action by the government, which will have drastic impacts on indigenous peoples.

The DNP used different rates to assess the “damages” caused by

the accused, depending on the type of forest and the type of damage

such as, for example, “loss of nutrients”, “causing soil not to be able to

absorb rain water” and “causing a rise in temperature”. The latter was

assessed at 4,453 Thai Baht (135 USD) per rai (0.16 ha) per year. The

methods used by the DNP to assess the cost of the “damage” are highly questionable in term of their scientific basis and accuracy. These calculations are not only based on rather arbitrary assumptions but betray a poor understanding of hydrological and edaphic processes in](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0001i2010eb-140101004315-phpapp01/75/0001-i-_2010_eb-353-2048.jpg)

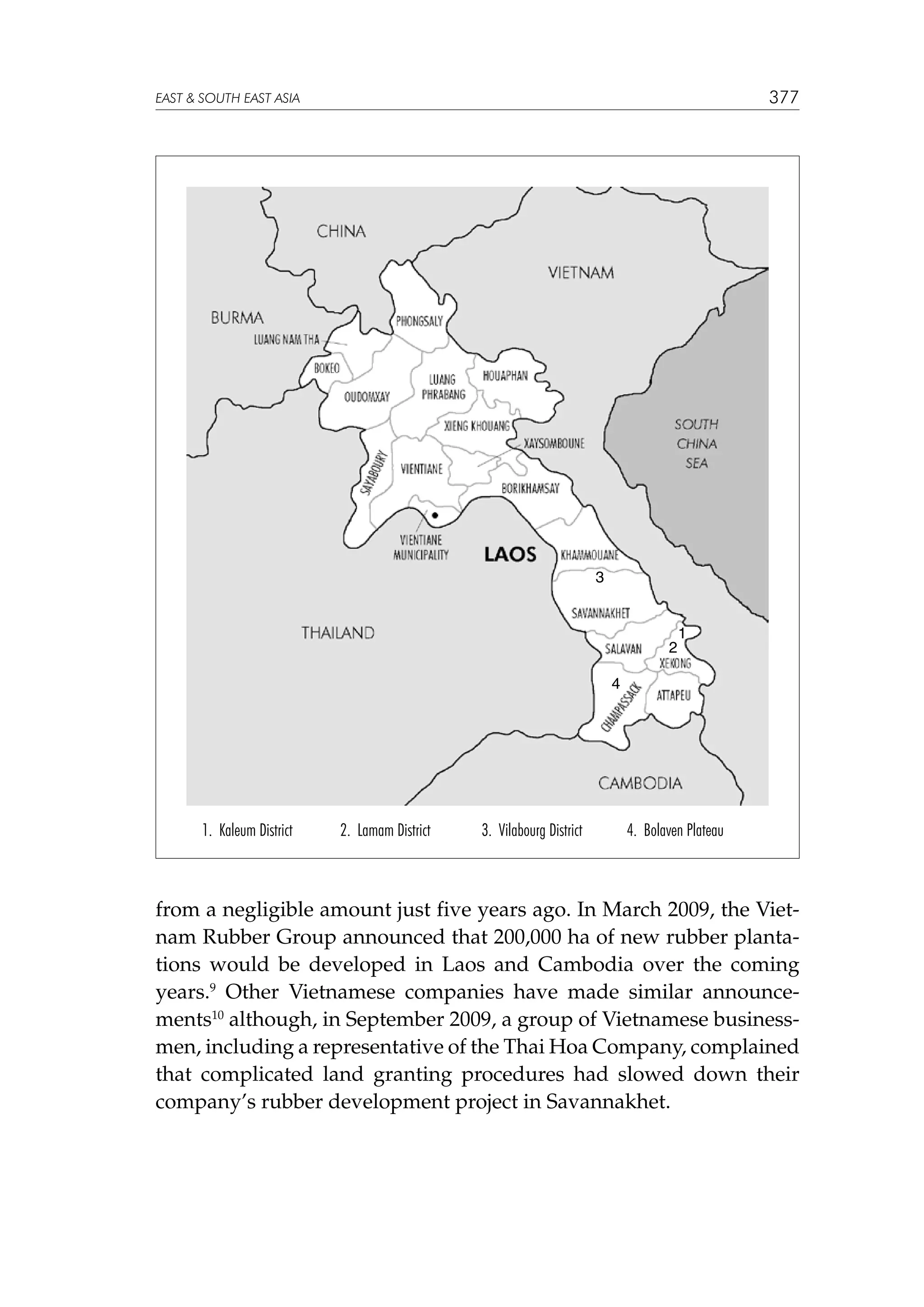

![376

IWGIA - THE INDIGENOUS WORLD - 2010

nous World 2009). In mid-2009, the government again began officially

issuing large land concessions, with concessions over 150 ha needing

the approval of the National Land Management Authority (NMLA).2

However, just a few weeks later the government announced that the

moratorium would be resumed. According to the Vientiane Times, during the week prior to the cabinet’s decision, members of the National

Assembly had urged the government to address problems of land concessions, claiming that people in their constituencies were complaining that these were having negative impacts on livelihoods and national protected areas.3 But it appears that the new moratorium is even

weaker than the first one. It only applies to concessions larger than

1,000 ha. More importantly, the Vientiane Times reported that, “[I]f an

urgent case arises, with an investor needing more than 1,000 hectares

of land to carry out a business, the sectors concerned will advise the

cabinet in making a decision”.4 Indeed, a number of large concessions

have been approved since the moratorium was reinstated.

Many questions are being asked about the wisdom of expanding

rubber in Laos. In 2008, international prices for rubber dropped rapidly, leading government officials to question whether planting so

much rubber was really the right decision.5 Also, some members of the

National Assembly have proposed that rubber expansion be frozen

due to land conflicts with local people.6 The deputy governor of the

predominantly indigenous Xekong Province, Phonephet Khewlavong,

who is himself from the indigenous Harak (Alak) ethnic group, told a

Vientiane Times reporter in July 2009 that the government was having a

hard time finding the land requested by investors for growing rubber.

He claimed that 19,000 ha of rubber had already been approved for the

province by central government but that so far only 5,000 ha had been

allocated. He also claimed that the province could not even provide

8,000 ha, as the land had already all been allocated as the private plots

of villagers, communal village land, forestry land and watershed protection forests. The deputy governor also claimed that increased mechanization and the use of herbicides in rubber plantations were leaving

villagers with less employment opportunities.7

Despite the Lao government’s land concession moratoriums and its

apparent desire to limit rubber expansion, as of June 2009 it was estimated that there were 180,000 ha of rubber plantations in Laos,8 up](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0001i2010eb-140101004315-phpapp01/75/0001-i-_2010_eb-375-2048.jpg)

![SOUTH ASIA

421

43 Naga seeks aid for displaced, The Telegraph, 2 April 2009 available at http://

www.telegraphindia.com/1090402/jsp/northeast/story_10760783.jsp

44 Information received from Asian Centre for Human Rights (ACHR), available

in ACHR. The State of Conflict Induced IDPs in India, a forthcoming report.

45 Human Rights Watch. 2008. India: Stop Evicting Displaced people,, 13 April 2008,

available at

http://www.hrw.org/en/news/2008/04/13/india-stop-evicting-displacedpeople

46 Burnt in oil: A fact-finding report on operation Green hunt in Dantewada in September-October 2009, op.cit.

47 Plight of internally displaced is of national concern: NCPCR, The Hindu, 18 December 2009 available at

http://www.hindu.com/2009/12/18/stories/2009121854970500.htm

48 Ministry of Tribal Affairs. 2010. Status report on implementation of the Scheduled

Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006

[for the period ending 31st December, 2009], available at http://www.tribal.nic.

in/writereaddata/mainlinkFile/File1190.pdf

49 Jhabua tribals denied land under Forest Rights Act, The Hindu, 27 August 2009

50 Entire village in Jharkhand faces arrest over felling trees, The Times of India, 6

February 2009.

51 Jharkhand withdraws 1L cases against tribals, The Times of India, 13 October

2009.

52 Govt will use secret key to unlock SC/ST quota jobs, The Asian Age, 14 December 2009.

53 Ibid.

54 Second Report of Parliamentary Standing Committee on Social Justice and Empowerment (2009-2010) (Fifteenth Lok Sabha) on Ministry of Tribal Affairs – “Demands

for Grants (2009-2010)”, Page 18 and 33, available at http://164.100.47.132/lsscommittee/Social%20Justice%20%20Empowerment/Report%20for%20

DFG%20(2009-10)%20of%20Tribal%20Affairs.pdf

55 Ibid.

Paritosh Chakma is Programmes Coordinator at the Asia Indigenous and

Tribal Peoples Network (AITPN) based in Delhi, India.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0001i2010eb-140101004315-phpapp01/75/0001-i-_2010_eb-420-2048.jpg)