1Health Insurance MatrixAs you learn about health care del.docx

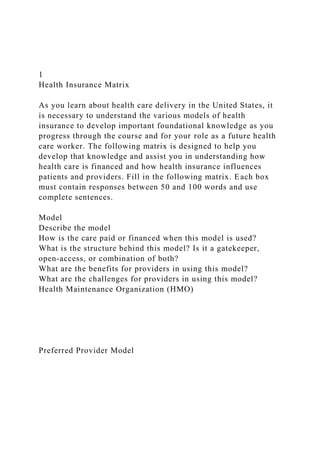

- 1. 1 Health Insurance Matrix As you learn about health care delivery in the United States, it is necessary to understand the various models of health insurance to develop important foundational knowledge as you progress through the course and for your role as a future health care worker. The following matrix is designed to help you develop that knowledge and assist you in understanding how health care is financed and how health insurance influences patients and providers. Fill in the following matrix. Each box must contain responses between 50 and 100 words and use complete sentences. Model Describe the model How is the care paid or financed when this model is used? What is the structure behind this model? Is it a gatekeeper, open-access, or combination of both? What are the benefits for providers in using this model? What are the challenges for providers in using this model? Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) Preferred Provider Model

- 2. Point-of-Service Model Provider Sponsored Organization High Deductible Health Plans and Savings Options Cite your sources below. References H 235: Health Care Services Textbook: Niles, N. J. (2014). Basics of the US health care system (2nd ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. Shi, L., & Singh, D.A. (2015) Delivering health care in America: A systems approach (6th ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning. Instructions: Please ensure to substantiate your response with scholarly sources and/or also a personal account of your own experience in the work place or personal life. Cite and reference work! QUESTIONS 1 – 11 USE TEXBOOK ABOVE & FOR QUESTIONS 1, 4 & 5 PLEASE SEE ATTACHED DOCUMENTS. 1. Read Chapter 8 Healthcare Financing and discuss what you

- 3. found the most or least interesting. See Chapter 8 attached. Must be 200 word count. 1. Glenn: This chapter covers the different types and costs of health care. According to our reading, the cost of health care increases about 6% annually, and the new concentration of the health care industry is controlling overall cost. In the past, health care spending was not controlled, so providers could submit a claim for reimbursement and be automatically reimbursed with no penalty or incentive to control spending. I am sure that many claims were summited that were grossly over estimated, leading to higher health care costs for insurance companies and the consumers. I thought that the portion CDHPs was interesting. CDHPs allow consumers to control health care costs by giving them the opportunity to save money for health care, by letting consumers bank tax free money from paychecks to use towards medical expenses. I wish the data was more up to date, because I seem to remember reading somewhere in the Los Angeles Times that health care costs were due to increase well above the average annual increase in 2015. I know that a lot of those costs get passed on to the consumer, and it would be interesting to see just how much of that is due to the affordable care act or "Obama care". What reactions do you have to the ideas they presented? Include examples from the course readings or your own experience to support your perspective, and raise questions to continue the dialogue. 100 to 150 words 1. Managed care model for Healthcare delivery was developed for the primary purpose of containing Healthcare costs. The industry felt that this model would be very cost-effective from administering both Healthcare services and the reimbursement of these services, and therefore eliminating a third party health insurer. As the managed care evolved the models developed allowed more choice for the consumer and the physician. Soon there were models that allowed consumers to more freely choose their providers. What reactions do you have to the ideas

- 4. they presented? Include examples from the course readings or your own experience to support your perspective, and raise questions to continue the dialogue. 100 to 150 words 1. Read Chapter 6 Health Services Financing and discuss what you found the most or least interesting. See Chapter 6 attached. Must be 200 word count. 1. Read Chapter 9 Managed Care and Integrated Organizations and discuss what you found the most or least interesting. See Chapter 9 attached. Must be 200 word count 1. This Chapter focused on the evolution of managed care through the 19th and 20th centuries, and how it has become the dominant trend that the majority of Americans use to obtain health care services. Managed care forced integration among health care providers and hospitals, and has continued to grow since the Affordable Care Act was put into play. It also. The chapter suggest that managed care will play a large role in health care insurance through financing from the federal government. This chapter also talked about the different forms of health care insurance and their models. For some reason I get drawn into HMO information, and I think it is because of Nixon and the Kaiser Permente group and how incredibly corrupt the whole thing seems. One other section that caught my attention was all of the statistics regarding the different forms of health care insurance and what the majority of people chose or have. PPO is very popular and I remember enjoying my PPO plan that I used to have, but it was like a hybrid between PPO and HMO. I had to pick an approved physician from a very large network, but could change primary care physicians as I saw fit. I also did not need a referral to see a specialist, which was probably what I enjoyed most. What reactions do you have to the ideas they presented? Include examples from the course readings or your own experience to support your perspective, and raise questions

- 5. to continue the dialogue. 100 to 150 words 1. What could be done to slow, stop, or even reverse the growth of health care expenditures in our nation? 200 words count. 1. U.S. health care expenditures have quickly risen in the last couple of years, creating stress on families, businesses, and public budgets. Health spending is rising faster than the economy as a whole and faster than a person's salary. In recent years, insurance administrative overhead has been rising faster than other sectors of health spending, while pharmaceutical seem to be spending more money than other health care services. I think the best bet is to address high and growing health care costs would involve the following: Getting rid of doubled up or unnecessary care and reducing administrative overhead, focus on preventative medicine in order to detect illness in its early stages, try and avoid any unneeded hospitalizations, and enhance productivity and effectiveness in providing care for patients. There might be a time when the nation may want to make a trade off between either spending money health care and other high national priorities, but there is a possibility that we can achieve savings and efficient payment, insurance, and care delivery systems and still be able to improve health outcomes, quality of care, and access to care. Some factors that tend to drive up the cost of health care are: introducing new technologies/innovations without comparative information on clinical outcomes or cost- effectiveness to guide decisions on adoption and use, wages and prices of other hospital-purchased goods and services growing market power and consolidation of insurers, providers, the health industry including pharmaceutical companies, device manufacturers, and other suppliers contributing to less choice and higher prices and the increasing prevalence of chronic diseases. What reactions do you have to the ideas they presented? Include examples from the course readings or your own experience to support your perspective, and raise questions

- 6. to continue the dialogue. 100 to 150 words 1. Why is long-term care one of the greatest challenges facing the health care delivery system today? 1. Read and discuss the article Investing in Value-Based Health Care in 150 words http://www.hhnmag.com/articles/6031- investing-in-value-based-health-care 1. Health Insurance Matrix There are 5 insurance models listed (e.g. HMO, point-of- service, preferred provider organizations, provider sponsored organization, and high deductible health plans and savings options), which you must fill out 5 columns for each insurance model. As you learn about health care delivery in the United States, it is necessary to understand the various models of health insurance to develop important foundational knowledge as you progress through the course and for your role as a future health care worker. The following matrix is designed to help you develop that knowledge and assist you in understanding how health care is financed and how health insurance influences patients and providers. Fill in the following matrix. Each box must contain responses between 50 and 100 words and use complete sentences. Model Describe the model How is the care paid or financed when this model is used? What is the structure behind this model? Is it a gatekeeper, open-access, or combination of both? What are the benefits for providers in using this model? What are the challenges for providers in using this model?

- 7. Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) Preferred Provider Model Point-of-Service Model Provider Sponsored Organization High Deductible Health Plans and Savings Options Cite your sources below. References . H 475: Leadership and Performance Development

- 8. Texbook: Ledlow, G. R., & Coppola, M. N. (2014). Leadership for Health Professionals (2nd ed.). Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett. QUESTIONS 12– 23 USE TEXBOOK ABOVE & FOR QUESTIONS 12 & 13. PLEASE SEE ATTACHED DOCUMENT. Must be 200 words 1. Read Chapter 6 Leadership CompetenceII and discuss what you found the most or least interesting. See Chapter 6 attached. 1. Read Chapter 10 ETHICS IN HEALTH Leadership and discuss what you found the most or least interesting. See Chapter 10 attached. 1. Leaders need to determine the values of the organization and hoe the organization holds themselves accountable. Many times this is done through systems, policies and procedures. We also need to take into account the patient, and how we ethically treat them. This means communication and listening to the patient. It also means that we need to protect their information. The information is also protected under HIPAA, but just the other day I saw another story on the news of a nurse taking pictures of a patient with their personal cell phone and sharing with their friends. Because this not only violated HIPAA, it violated the hospitals code of conduct and ethics. The nurse was terminated and may face criminal charges too. To keep the policies up to date and relevant it is important to have a committee that meets monthly to discuss and ensure that the hospital is holding true to their core ethics. Fostering a positive environment that allows a positive ethical open communication. What reactions do you have to the ideas they presented? Include examples from the course readings or your own experience to support your perspective, and raise questions to continue the dialogue. 100 to 150 words

- 9. 1. How do you think managers and leaders use the problem- solving steps differently? 200 words 1. Leaders find an issue or problem and they look to solve them for long term or they look to stop the issue or problem permanently. Managers for the most part look at a problem or issue and want to stop it but do not normally look for a long term solution. They usually just want to fix it and move on with no view of looking at the big picture. How does your manager look at issues or problems? Does your manager see the big picture? 100 to 150 words 1. When I am giving someone a chance to solve a problem I like to let them take the lead and if they need help from me they can ask otherwise I follow up with them after they say they have completed the problem. I talk to the other employees and see how they feel about the way the leader worked with them then I follow up with the leader. Class how important is it to follow up with the leader to help the see how their problem solving skills were accepted by the employees? 100 to 150 words 1. It is good to have someone to plan with. When there are issues you must have someone to work with and someone you can depend on. I normally work with managers that I feel can see the big picture and those are the types of managers that I like to hire so we can bond as a team. I like to have someone that I can give issues to and depend on them to get the job done. Class when you hire someone what characteristic are you looking for? 100 to 150 words. 1. Provide at least two specific examples of situations in your life in which you have seen the benefits of delegation. What have you seen as being obstacles to effective delegation? 200 words

- 10. 1. Delegation is an art and if you use it right you can get a lot of work out of your employees but you must follow up with them to make sure they have completed their task. I asked an Assistant Director of Nursing to go to all the rooms in the nursing home and make sure that all clothes were at least 18 inches from the ceiling in their closets because we were having an inspection and that was one of the first things the inspectors will look for. The inspectors came in and wrote us up for that the first day and I went to her and asked her why she did not do what I asked and she said she asked the CNAs to do it. I asked her if she followed up with them to make sure they completed the tasks and she said no. How important is it to make sure the person delegating follows up to make sure the task is completed? 100 to 150 words. 1. How is understanding the problem-solving process helpful when working within a team? What techniques have you used to ensure your team is effective? 200 words 1. What steps are involved in the delegation process? Are there any steps that should be included that are not already included? How does an effective delegation process affect an organization? Provide an example of a time when you applied problem-solving steps to resolve a specific situation. What did you do effectively? What could you have done better? 200 words 1. The Importance of Accountability Paper Grading Criteria- Write a 1,050- to 1,400-word paper that addresses the following: · Why is accountability important in the health care industry? · How is an employee's accountability measured in the health care industry? · How does accountability apply to ethical considerations in leadership and management? · What does a checks-and-balances process look like in a

- 11. successful organization? · How does accountability affect an organization's working culture? · How can you maintain a positive working culture and avoid a working culture of blame? Cite a minimum of 4 references. Format your paper according to APA guidelines. CHAPTER 10 Ethics in Health Leadership © artemisphoto/ShutterStock, Inc. Healthcare executives should view ethics as a special charge and responsibility to the patient, client, or others served, the organization and its personnel, themselves and the profession, and, ultimately, but less directly, to society. American College of Healthcare Executives, 2009 In recent years, the United States has seen the near-collapse of much of its banking system. In hindsight, the chaos was largely attributable to unethical practices and procedures enacted by a few unscrupulous, greedy members of the industry. With the collapse of WorldCom and Enron—both companies that manipulated the stock market and defrauded investors—and the conviction of Bernard Madoff, the mastermind behind a record- setting Ponzi scheme, higher education is realizing the essential need to study ethics and to incorporate those ethical principles and moral practices into the development schema of the next generation of business and health leaders. In support of this view, a review of the top 50 master of business administration (MBA) and master of health administration (MHA) programs in the United States over the last 5 years, as profiled by U.S. News and World Report, suggests that many graduate programs are

- 12. incorporating ethics-based courses into their curriculums. Clearly, it is critical for nascent health leaders to study health ethics so that they can develop a sound foundation upon which to base decisions, allocate resources, and develop organizational culture. This chapter presents the ethical responsibilities of health leaders from an organizational perspective. Several ethical theories and frameworks are presented as structures to open up the discussion of ethics. Additionally, regulatory compliance, essential to organizational morality, is presented from the aspect of a health organization. The chapter also discusses professional, educational, and contractual relationships affecting the operation of the health organization. LEARNING OBJECTIVES · 1. Define distributive justice, ethics, morals, values, promise keeping, and leadership bankruptcy. Describe how they are used by leaders in decision making based in an ethical framework. · 2. Explain four ethical principles and four statutes or regulations that guide decision making associated with patient care. · 3. Apply at least two ethical frameworks or distributive justice theories, with examples of moral practice of a leader, to an ethical issue in a health organization. · 4. Analyze arguments and make a recommendation for health leaders to adopt utilitarian or deontological postures in their organization, and differentiate potential decisions leaders would make between the two frameworks to support your analysis and recommendation. · 5. Compile a list of options that a leader in a health organization has to develop for an integrated system of ethics and moral practice, and summarize the potential impact of each option regarding appropriate ethical adaptation across the organization. · 6. Compare and contrast at least three ethical frameworks or distributive justice theories for the topics of patient autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice, and interpret the

- 13. moral practice associated with those frameworks (at least three) for a right-to-life issue and for the practice of euthanasia. INTRODUCTION Defining ethics can be difficult. According to Pozgar, ethics is a moral philosophy between concepts of right and wrong behaviors. Pozgar suggests that ethics “deals with values relating to human conduct with respect to the rightness and wrongness of actions and the goodness and badness of motives and ends.”1 In the context of the health leader, ethics refers to a set of moral guidelines, principles, and suggested standards of conduct for health professionals. All health leaders, regardless of their status as patient care providers, encounter ethical dilemmas or challenges.2 The ethical tone and moral expectations in any organization are set by the leader. Unethical leaders set the stage for harmful activities and outcomes that will eventually affect all people and all stakeholders in the organization. It may be said that ethical leaders have a moral responsibility to treat their followers with dignity and respect, and that they must act in ways that promote the welfare of others—most immediately, the welfare of their followers. This consideration is of particular importance for health leaders who rely on actions that involve intrinsic aspects of an individual’s values and behaviors to achieve motivational and goal-directed outcomes that support organizational success. Health ethicists have suggested that health organizations have an ethical and moral obligation to provide care that is not only of high quality, but also ethically driven and managed.3 Too often, ethics, ethical practice, and discussions of ethics are placed in a legal context of liability reduction and “legalism.” In fact, the ethical component of many U.S. educational degree programs, both undergraduate and graduate, is embedded in some sort of “legal” or “law” course; the practice of ethics in a profession is likewise relegated to a “legal counsel office.” This reality is based on the litigious environment of the health industry; lawsuits and settlements for breaches of ethical

- 14. expectations and errors in health services delivery run rampant in today’s world. Health leaders model the behavior expected in the organization, including being a moral actor—a visible moral actor—in the health organization. Remember, leaders “do the right thing.” Sometimes doing the right thing does not always agree with actions that limit the organization’s legal liability, but that has to be the leader’s decision. By the end of this chapter, you should be able to answer a key question in this arena: How will you balance “legalism” and “leadership practice” with regard to ethics and moral practice? WHAT IS ETHICS? Professional organizations and prospective employers frequently suggest that they are looking for ethical leaders. In response, we might ask ourselves, “What is ethics?” Within the literature, ethics is defined as a moral philosophy that focuses on concepts of right and wrong behaviors as linked to resource allocation. It deals with values relating to human conduct with respect to the rightness and wrongness of actions and the “goodness” and “badness” of motives. Ethics in the health field can further be defined as a set of moral principles and rules of conduct for health professionals to follow.4,5 Ethics can, at times, be culturally defined. What may be considered ethically and morally appropriate by one culture may be seen as inappropriate and immoral by another culture. For example, the triage and medical treatment of persons by gender, race, and age may be unethical, if not illegal, in the United States. In the United States, providers may find it extremely unethical to make medical decisions based on a patient’s age. In fact, Americans may find it extremely distasteful that some countries with socialized medicine and national healthcare systems ration medical care for certain ailments for patients who have passed a certain age.6 Americans find this form of triage “unethical” or, more simply, “not the right thing to do.” At a general and broad level, however, the United States holds to a system where medical triage is based on a patient’s ability

- 15. to pay. In many ways, persons who have health insurance coverage have access to the entire continuum of care, whereas those without coverage are severely limited in their ability to access the appropriate services within the continuum of care. Many democratic nations find the practice of basing medical care on remuneration “unethical,” and not in keeping with the practice of “goodness.” This practice, they suggest, violates a sense of beneficence and distributive justice attributed to health services. Clearly, ethics may not only be cultural driven, but also nationally recognized and lawfully upheld based on the beliefs and cultural norms advocated by a national government.7 Despite the ineffable and difficult-to-understand nature of ethics, health leaders should study ethics so that they can better understand the human condition and better appreciate the differing points of views presented in the environment. Areas in health where ethics may assist in decision making are highly eclectic. For example, the study of ethics can assist in decision making associated with finance, risk management, resource allocation, customer advocacy, law, and organizational standing policies, to name only a few areas. A health leader in possession of a wider point of view of the dynamic field is better able to handle the complex and challenging issues presented to him or her. This chapter covers some of the areas from which both an early careerist and a seasoned professional may base ethical decision making. The Difference Between Ethics, Values, and Morals Ethics is the practice of “goodness and rightness” over “wrongness and badness” within a system of resource allocation and preferences. These principles are based on several factors gleaned from a myriad of experiences, which include, but are not limited to, constructs of values and morals. Societal norms and mores greatly influence ethical frameworks and moral practice; those norms and mores are embedded in the beliefs and values held by the members of that society. Values are enduring beliefs based on some early form of

- 16. indoctrination and experience. They are learned from parents, the community, school, peers, professional organizations, and personal self-development, to name only a few areas. Values inform beliefs; beliefs facilitate the development of attitudes; and attitudes contribute to behaviors. Changing attitudes is easier than changing beliefs; in turn, changing beliefs is easier than changing values. A health leader’s values provide a basis from which to make decisions and establish preferences. For example, one controversial health debate centered on values focuses on a fetus’s right to life. Health leaders who have embraced a belief from their own personal experience that life begins at conception may question the “ethics” of abortion. Such an early belief may be based on spiritual experiences or parental teachings. These enduring beliefs are difficult to change and are rarely modified within an individual’s lifetime. All values are based on some internalized experience or learned behavior. To unlearn and reorient values is difficult; value change is a complex issue for any individual. Morals are applied practices derived from an ethical framework that is based on values and beliefs. These practices are based on behaviors learned through experience and internalized principles. Different from values, morals comprise the principles on which decision making is based. Morality is the level of compliance to an ethical framework. One way of conceptualizing morality is to think of it as a yardstick that measures each action, decision, or distribution of resources from the standpoint of the accepted ethical framework of a society, organization, community, group, or individual. Principles are those immutable characteristics of value-based decision making that are broken down into mutually exclusive categories (nominal data) of outcomes or answers such as “yes/no” or “I strongly agree/agree/disagree/strongly disagree” (ordinal data). A principle may be a screening behavior upon which a decision is based. For example, one principle may be the belief, “All those who break the law need to be punished.” Once this screening criterion is put into place (yes/no, I

- 17. agree/disagree), the second step in the process may be acted upon. The progenitor step is to take action and to continue with the consequences of that principle based on an action; in this case, the action is to determine the degree of the punishment. In this second stage, more values-based and evaluative criteria are put into place based on the circumstances and factors associated with the actual breaking of the law. Because values are evaluative and subject to interpretation, a values-driven behavior of providing a “second chance” may result in no punishment for the law breaker or a larger consequence and penalty if forgiveness is not an option in the evaluative process. Following this discussion, we can simply say that morals are the actions and outcomes of the human condition processed over time as evaluated against the ethical framework based on values and resource allocation principles. They arise when values, principles, and preferences (and other factors) are generally internalized through lived experiences. In reality, these lived experiences may take years to compile and practice. Because morals are so difficult to embrace without lived experiences, they are generally taught through storytelling and lessons. Consequently, we learn about the lived experiences of populations in communities, groups in the organizations, and individual experiences in one’s own life through the sharing of moral tales. One such example is the moral tale of the Grasshopper and the Ants from Aesop’s fables. In Aesop’s fable, the ants diligently work through the warm summer days preparing for winter by constructing a summer nest and stockpiling food. During the period of time when the ants are working hard, the grasshopper plays the days away singing (Figure 10-1). When winter finally comes, and no food or shelter can be foraged above ground, the grasshopper finds itself starving and cold, while the ants are warm and well fed below ground. It is then that the grasshopper states the lesson of the story: “It is best to prepare for the days of necessity.”8 As an analogy, a health leader might simply suggest that eating right and taking care of your body and mind today ensures a

- 18. higher quality of life tomorrow. FIGURE 10-1 The Grasshopper and the Ants. Source: Reproduced from The Aesop for Children with Pictures by Milo Winter. Copyright © 1919, by Rand McNally & Company. The “moral” of this story is that it is always best to prepare for one’s future in the face of the uncertainty of the environment. However, because this “lived experience” may take an individual’s entire lifetime to learn, the experience is shared through the lived experience of others through moral tales. Similar to propositional statements, morals can be statements of opinion presented as if they were true. As a result, they become the “moral compass” by which some leaders conduct their lives in both the personal and professional spheres. Setting an Ethical Standard in the Health Organization Health leaders face ethical dilemmas in their daily work of delivering health services and products within the health organization. This stands in contrast to the experiences of their “strictly business”-oriented peers in a nonhealth, for-profit environment. In respect to patient care options, the ethical considerations of the health leader may often be tied to those of the physician, but not always. The physician’s ethical duty derives from the Hippocratic Oath and (for many) Section 5 of the Code of Ethics of the American Medical Association, which states that in an emergency physicians should do their best to render service to the patient, despite prejudice of any kind. By comparison, the health leader of an organization may have less of an ethical and legal duty to provide care that exceeds the standing policies and procedures established by the governing board. Health leaders may often find themselves torn between owing allegiance to the financial stability of the organization and the charitable nature of the health profession. As a result, the health organization’s policies, screening criteria, and guidelines for services (such as preadmission procedures in a hospital) may often come into conflict with the health of the

- 19. patient and the patient’s compensatory reimbursement potential. Many hospitals attempt to overcome this dilemma by achieving a balance between the business aspect of operating a health facility and the social aspect of caring for the indigent through the establishment of ethics committees within their managed care organization.9-11 Another critical element is the incorporation of stakeholders’ ethical expectations for the health organization. Stakeholder expectations are expressed and integrated into the organization in the following ways: through the board of directors or board of trustees membership, which represents the communities served; through advocacy on behalf of stakeholder expectations carried out by senior leadership of the health entity; and within internal committee structures of the organization, such as with the ethics committee. Establishing an ethics committee, in particular, is a necessary element in health organization operations and strategy. The ethics committee has three main purposes: education, consultation, and policy review. Challenges faced by the members of this committee include conflicting internal organizational principles, values contradiction, leadership team decision making, and community and industry ethical attitudinal changes. Other challenges include targeted education, proactive initiatives, and accreditation. Finally, it should be noted that the ethics committee seeks to assess implications for stakeholders during its review of policies. Stakeholders may include the institution and its culture, patients, individuals who receive training in the institution, volunteers, and other health providers in the region.12,13 To aid in the establishment of an ethical organization, the health organization should have an individual appointed on staff as the resident ethicist to assist in decision and policy making. The establishment of an ethics committee that meets on a regular and reoccurring basis can likewise keep the leadership informed of relevant and legitimate ethical issues confronting the health organization.

- 20. The health leader may partner with outside stakeholders and agencies to ensure it is meeting certain ethical norms and standards within the environmental setting.14 Moreover, the organization can seek guidance from ethical policy statements and positions published by such organizations as the American College of Healthcare Executives (ACHE), the American Hospital Association (AHA), the Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), the Association of University Programs in Health Administration (AUPHA), the Joint Commission, state organizations, and other regional quasi-government organizations. Health leaders who are leading a well-rounded organization made up of participatory stakeholders and consumers will ensure that the organization’s posture on policies and principles regarding ethics is maintained consistently.15 A health leader must remember that it will never be enough to have an organization that claims that it is an ethical entity; rather, it must behave, advocate, and have systems that foster moral action, such as having recognized committees or boards that separately address clinical and/or research ethics. One such committee is the institutional review board (IRB), the entity that reviews and approves research within a health organization; its role is especially important in the review and strict adherence to human subject laws, policies, and procedures. These ethically associated committees or bodies must have the power and the ability to act and foster change.16 Unfortunately, according to national polls, 50% of health ethics committee chairs feel inadequately prepared to address issues in the health environment.17 To overcome this problem, a wise health leadership team will invest in professional education and training of the organization’s chief ethicist, as well as the members of the committees that make up any advisory panels within the faculty. This investment may offer dividends in future complex leadership dilemmas. Example: When Actions and Ethics Collide During the financial collapse of many U.S.-based organizations

- 21. in the fall of 2008, Congress reacted by providing more than $700 billion to organizations that had run themselves into the ground through bad business practices and risky financial behaviors. It was later learned that the CEOs of many of these financially insoluble organizations would receive annual bonus checks of as much as $620,000.18 The public was outraged that the leaders of these mammoth financial institutions could be rewarded for incompetency that ruined the financial health of their own organizations and sent hundreds of employees to the unemployment line. Many industry leaders replied by stating the bonuses that were received were contractually legal. Taxpayers countered by suggesting that although the bonuses may have been legally provided, it was unethical to receive such bonuses when so many people were out of work, and when so many outside stakeholders, including taxpayers, had assumed financial responsibility for the corporate mess. In an effort to establish a new leadership and ethical tone during the financial collapse of 2008–2009, and in response to taxpayer outrage, one financial organization, American International Group (AIG), made an attempt to change the message. AIG’s CEO, Edward M. Liddy, stated that, “I have asked the employees of AIG Financial Products to step up and do the right thing. Specifically, I have asked those who received retention payments of $100,000 or more to return at least half of those payments.”19 In response to his request, 15 of AIG’s 20 executives receiving the highest bonuses later agreed to return the money. This good-faith, ethical gesture helped AIG to reclaim some of the public’s trust in the banking industry. Common Ethical Dilemmas in Health Organizations Ethical dilemmas in health organizations generally arise out of professional or values-based conflicts of interest. According to the American College of Healthcare Executives, a conflict of interest occurs when a person has conflicting duties or responsibilities and meeting one of them makes it impossible to meet the other. The classic example occurs when a decision

- 22. maker for one organization is also a decision maker or influencer for another organization with which business is transacted. Often, the potential conflict of interest becomes an actual conflict of interest because the decision maker cannot meet the duty of fidelity (loyalty) to both organizations when a decision that impacts both is needed.20 Relationship Morality Ethical dilemmas in the health organization are inevitable. In the field of health leadership, such dilemmas occur at three levels: micro, macro, and meso. The micro level involves individual issues, such as relationships between individuals and leaders. An example of a micro-level ethical dilemma in the health setting is the reduced decision- making power accorded to some health professionals, such as a physician being forced to order a cheaper test with less diagnostic power. The micro level of management usually is dyadic, occurring on a person-to-person basis. It is exemplified by health professionals who work directly with patients and face a number of ethical dilemmas in a provider-agent role. Health leaders should remember to praise in public and correct in private. All positive actions, behaviors, or performance and, especially, all negative actions, behaviors, or performance (extra emphasis on ethical breaches) should be documented regarding subordinates, staff, and peers. If you observe an ethical breach by a superior leader, privately discuss the issue with the individual and ask the person to correct the situation and report the issue to his or her superior leader. If the individual refuses or does not comply, it is your duty to discuss the ethical breach with that person’s superior leader. This is tremendously difficult to do—but it is the right thing to do. Always confront the leader who has committed an ethical breach immediately and, at first, privately; always document the scenario in a confidential memorandum that you keep in a secured location unless you need to provide evidence to senior leadership at a later time. You cannot let ethical breaches go without confronting the person who committed the ethical error;

- 23. you cannot let the ethical breach go uncorrected and unreported. If you do, you are modeling a negative behavior—namely, corruption and ethical cover-up. Although the choice is sometimes difficult, it is up to you to decide to be moral (or not). This decision-making process includes not only your actions and behaviors, but also, as a leader, the actions and behaviors you observe in others. The macro level of ethical dilemmas involves societal or community issues that reflect governmental actions or social policies. These dilemmas are typically culturally based. For example, closing down a hospital’s emergency department when it may be the only source of entry into the health system for the uninsured may be a prudent business decision, but the lack of consideration shown for the impoverished by this decision may violate the value of the health organization’s responsibility to provide care. The meso level involves organizational or professional issues. A restrictive agreement between health organizations and managed care organizations, such as the use and contractual arrangement for durable medical equipment, is an example of a meso-level ethical dilemma.21 Business and Financial Ethics Business and financial ethics has been acutely observed since the Enron and other scandals began to erupt at the beginning of the twenty-first century. The Sarbanes-Oxley Act, which requires a firm’s senior leader to validate and confirm financial statements and performance, is a governmental reaction to the public outrage over unethical business and financial behavior by organizations. Health leaders need to deal fairly and honestly in business and financial matters. In the health business, telling the truth is paramount. Of course, telling every financial or business secret and breaking confidentiality are neither reasonable nor moral. If you cannot tell the truth, it is better to say nothing. The golden rule applies to business and financial operations of the health enterprise: “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” Avoid and acknowledge

- 24. conflicts of interest; remove yourself from situations where conflicts of interest might compromise your ability to make decisions fairly. Follow the law, regulatory requirements, accreditation recommendations, and good business practices. Never leverage “good” for “bad” intentions. Build systems that are efficient, effective, and efficacious while treating people with respect, dignity, and honesty. Apply those same principles to the moral application of day-to-day business activities. This is never more important than when you are in discussions with bond raters; those organizations decide your organization’s bond rating (e.g., AAA, B, C), which has a direct correspondence with the interest rates charged on your organization’s loans. Tell the truth, and act according to that truth. A good bond rating, for example, does not get better if trust is broken; a poor bond rating does not get better with broken trust. These ratings do improve, however, if trust is the basis of discussions and interactions. In addition, health organizations must have regular external audits of their financial records, flow of funds, and policy compliance, conducted by a firm with a solid reputation. Especially important is the audit of financial information and systems of claims and reimbursement to taxpayer-funded programs such as Medicare and Medicaid. If errors or systemic problems are found, either by the external audit firm or by internal staff, immediate communication with the appropriate fiscal intermediaries and government agencies must occur. As an ethical health organization, application of this process is also appropriate with any commercial payer or for any contract with an outside entity. Contracts and Negotiations Ethical standards regarding negotiations and contracts are of particular interest and importance. Whenever a health organization is engaged in a negotiation or contract process, the organization is most likely working with some external entity. A successful negotiation usually concludes with a contract; this contract may be written or verbal and should specify terms,

- 25. conditions of performance, payment, liability conditions, and outcomes if either party breaches the contract (i.e., does not perform its agreed-upon actions to the level of quality stated). Representing the health organization honestly by stating the needs and conditions of a particular negotiation or contract event, the elements of performance, the payment, and the commitment to comply with the ultimate terms are paramount in this type of negotiation. A successfully completed negotiation and signed or verbally agreed-to contract must be complied with; when compliance may be at risk, communication with the other party or parties must occur in a timely fashion. Negotiations and contracts should include involvement of the health organization’s legal counsel to ensure compliance with all applicable laws and regulations, and to ensure a reasonable amount of liability protection. All negotiations and contract processes should consist of well-thought-out elements that adhere to the values and ethical expectations of the organization. Health leaders must not engage in negotiations or contracts that are inherently illegal—for example, making inappropriate payments. This is the professional ethical expectation for all negotiations and contracts. Right-to-Life Issues It is not possible for a health leader, especially a CEO, of a large and munificent health organization to avoid policy discussions on right-to-life issues. The term right to life has transcended boundaries in the recent era and is no longer associated with only abortion-related issues. Health leaders will find themselves faced with a variety of right-to-life issues that include abortion, the death penalty, and euthanasia. Despite the increased number of situations associated with the generalization of right-to-life issues, health leaders in government, secular, nonsecular, for-profit, and nonprofit health organizations alike will be faced with decisions brought to their attention regarding abortion issues from the medical staff, stakeholders, and patients. In response, they may have to

- 26. issue a policy statement on abortion procedures in the facility or provide institutional guidance on the practice. In doing so, health leaders must balance their personal views and organizational goals simultaneously and perhaps select one value and principle over the other if the personal and professional dilemmas related to abortion procedures cannot be reconciled. For health leaders who have very specific and partisan views regarding abortion, the selection of a health organization as an employer may need to be carefully evaluated. For example, if you believe that abortion is wrong and immoral, seeking a position in a health organization that refuses to abort a fetus should be your focus. Many religious-based health organizations, such as Catholic-, Lutheran-, Baptist-, and Methodist-based or value-founding organizations, will not perform procedures that go against their values regarding right to life. The famous Roe v. Wade debate is an example worth noting regarding the contradiction of values within a society. These contradictions in values, especially as health is concerned, in a society are at the heart of ethical challenges faced by health leaders. As health leaders progress up the ladder of responsibility and accountability, the ethical issues encountered become both more frequent and more challenging. Roe v. Wade The following excerpt was adapted from Harris’s Contemporary Issues in Healthcare Law and Ethics:22 · In 1973, the U.S. Supreme Court delivered a decision in the case of Roe v. Wade based on a woman fictitiously named Jane Roe who sought an abortion in the state of Texas but did not “fit within the sole exception” as a medical necessity to save the life of the mother. The ruling gave women the right to abort a fetus for any reason up until the fetus became viable. The term viable was defined as a fetus brought to 28 weeks gestational age, or a fetus that could live on its own outside the womb with reasonable medical aid. Women were still given the option to

- 27. pursue an abortion after 29 weeks if there was/is substantial cause to protect the life of the mother. · The Court further ruled that the Texas abortion statute violated the constitutional right of personal privacy and it “emphasized the physician’s right to practice medicine without interference by the state.” The ruling additionally gave states opportunities for placing more regulations and statutes to protect maternal health and potential life. · In 1992, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on the case of Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey, in which the court upheld the ruling of Roe v. Wade [stating that] a woman had the right to terminate a pregnancy prior to the point of viability, but the court rejected the trimester framework as previously ruled in Roe v. Wade. However, the court left open the interpretation of “point of viability” to future medical developments. · In 2000, the Supreme Court ruled that a statute banning partial-birth abortions in Nebraska was unconstitutional as it contained an exception to “preserve the life of the mother,” but not an exception to “preserve the health of the mother.” In 2002, President George W. Bush signed into law the Born-Alive Infants Protection Act, which treats every infant who is born alive, including those as a result of abortion, as a “person.” The debate continues. Euthanasia Euthanasia can be defined as the active termination of an otherwise viable human life in a painless manner. It can also be defined as a passive methodology in which life-sustaining treatment is withheld or withdrawn. Euthanasia issues are generally grouped with right-to-life issues in health facilities, and provide similar dilemmas for leaders to ponder. Euthanasia is becoming an acceptable alternative to heroic medical care as some patients are securing advanced directives that state life support should not be provided to them under certain medical conditions. Research also suggests that hospice and palliative care may actually increase incidence of

- 28. euthanasia requests, because individuals who seek out these services are more accepting of their condition and may be more likely to “plan” for their deaths. Additionally, the concept of the “slippery slope” may be justified in the argument against legislation of voluntary euthanasia for elderly individuals who are pressured to “opt for death when they perceive themselves to be a burden for loved ones.”23 THE ETHICS OF POLICY MAKING AND TREATMENT IN THE UNITED STATES The first thing U.S. healthcare leaders need to understand is that our view of healthcare ethics in regard to medical treatment and healthcare access is very different from that of many other countries. Healthcare ethics is defined very differently by other nations. We also need to know that ethics in health care can, at times, be culturally defined. What may be considered ethically and morally appropriate for one culture or one nation may seem to be inappropriate and immoral to another culture or nation. As mentioned earlier in the chapter, the triage for medical treatment of persons by gender, race, and age may be unethical, if not illegal, in the United States. In the United States, we find it extremely unethical to make medical decisions based on a patient’s age, gender, or race. In fact, Americans may find it extremely distasteful that some countries with socialized medicine and national healthcare systems do ration medical care for certain aliments for patients who have passed a certain age. American’s find this form of triage “unethical,” or simply, “not the right thing to do.” However, the United States has a system in place where medical triage is based (in some cases) on a patient’s ability to pay. Many nations outside the United States find the practice of basing medical care on remuneration “unethical,” and not in keeping with the practice of “goodness.” To some cultures and nations, the U.S. healthcare policy of basing care on payment violates a sense of beneficence and distributive justice. Unique to the U.S. healthcare system is the availability of healthcare treatment and access through a variety of financial-

- 29. based structures, such as for-profit, not-for-profit, county, state, and government entities (to name the major actors in the field). However, each entity will have unique stakeholder dynamics guiding its views and policies regarding reimbursements, uncompensated care, and unfinanced requirements for quality initiatives. Ethics and Advocacy The definition of advocacy in the legal sense is the act of pleading for, supporting, or recommending; however, in the health professions, the application of this perspective is problematic because health providers must consider whether advocating for one patient will in any way compromise the health of this individual or of others. In the current structure of the U.S. health system, professionals also must often weigh the quality of care versus the cost of that care. Advocacy is also an effort that must contribute positively to the exercise of self- determination. It is the effort to help patients become clear about what they want in a situation, and to assist them in discerning and clarifying their values and examining available options in light of those values. A patient’s right to self- determination is often a source of moral contention, because this fundamental right is constrained by the patient’s limited knowledge of his or her health issues and inexperience with the healthcare system. As a result, patient advocacy is not an optional activity for health professionals; however, most professional organizational codes lack a discussion of how health professionals can best apply advocacy in practice.24,25 Understanding the Patient’s Spirituality Base in Decision Making Despite the Joint Commission’s 2010 publication, Advancing Effective Communication, Cultural Competence, and Patient- and Family-Centered Care, which specifically identifies the importance of understanding spiritual beliefs and practices as part of the domain for provision of care, healthcare executives and providers are hesitant to openly discuss spirituality in their organizations. However, it is well known that spiritual

- 30. principles are the basis for many decisions made by consumers in today’s healthcare environment. Furthermore, policies and procedures currently in place in many healthcare organizations may already be linked to spiritual principals—albeit they are presented as ethical, cultural competence, clinical, and/or bioethical practices. Within the health and general leadership environment, the topic of spirituality in leadership is often considered taboo and may even be a career-ending conversation for executives and practitioners. This stance is beginning to soften in society; spirituality in leadership is beginning to be discussed more openly in more organizations. At the same time, it is well known that spiritual principles are the basis for many values and enduring beliefs that guide the moral and ethical development of health leadership practices in our society.26,27 Therefore, spirituality as a construct of discussion and examination in health leadership practice should not be overlooked in future research examining leadership theory. A national survey of spirituality conducted by Baylor University in 2011 reaffirmed that over 85% of the U.S. population consider themselves religious. Furthermore, this same study suggested that over 75% of the U.S. population believes that God has a purpose for their lives. Certainly, spirituality plays an important role in the decision to use, and consume, health resources. A similar study of Canadians found that 72% claimed to have spiritual needs, and 70% believed in miraculous healing. These factors have tremendous implications for health professionals in terms of meeting the physical, emotional, and personal needs of their patients and their patients’ families. As Pesut has suggested, “professionals are now expected to play a role that was once borne by the institutional church, which may include helping individuals to reconcile spiritual beliefs with their health care decisions.”28 Within the study of leadership theory, it has been suggested that the distinct absence of the study of spirituality in ethics and

- 31. leadership results in a gap in the process that seeks to understand the decisions ultimately reached by patients in regard to end-of-life decisions. End-of-life decisions, do-not- resuscitate requests, cord blood recovery, stem cell studies, pregnancy termination, sexual abstinence, organ donation, and volunteering for human subjects research are only some of the relevant issues faced by patients and families for which spiritual teachings (spanning a variety of religious affiliations) are known to influence decision making. Healthcare executives and providers are similarly faced with issues in decision making, healthcare policy interpretation, and ethics for which both judgment and course of action selection are influenced by those enduring beliefs learned through spiritual teachings. Unfortunately, spirituality is often directly omitted from these important conversations regardless of known influence. As a result, the concept of spirituality in leadership should not be overlooked when discussing ethical decisions in the modern health environment.29-31 To adjust to the spiritual needs of patients entering the health system, leaders should strive to be aware of the diverse beliefs within their organization and foster a high degree of sensitivity and respect for those beliefs. Specific beliefs and practices to consider include, but are not limited to, the following: · • Healing rituals · • Dying, death, and care of dead bodies · • Harvesting and transplanting organs · • End-of-life and right-to-life decisions · • Use of reproductive technologies In an article published in 2009 titled “Incorporating Patients’ Spirituality into Care Using Gadow’s Ethical Framework,”32 Pesut suggests that there is a growing need to address spirituality in client care. In addition, Pesut notes that several health professional organizations are now addressing spirituality as an ethical obligation to care. She further states that in many situations, spiritual values and beliefs provide a source of encouragement as patients endure experiences of

- 32. suffering. One challenge of addressing spirituality in health is the use of language and narratives that may be foreign to health professionals outside of a specific faith. Language and terminology that are consistent and easily understood by one faith-based group of individuals may be misunderstood or misconstrued by an individual unfamiliar with that faith-based group’s tradition. As an elementary example, if we describe our friend Pat as a “religious person,” are we operationalizing “religious” as someone who is spiritual, or someone who is Christian, Confucianist, Mormon, or Muslim in that they are in good concordance with that particular mindset and belief system? In conclusion, although understanding faith-based beliefs is important for health professionals so that they will be sensitive to and respectful of those beliefs, the leader should be careful when asked to provide faith-based advice. ETHICAL CODES ADOPTED BY THE HEALTH INDUSTRY Over the last 100-plus years, guidelines, codes, and other regulations have been created to help guide the conduct of research involving human participants. Some of these guidelines were created in response to ethical lapses in judgment committed by individuals or organizations. Other guidelines have evolved in an attempt to provide answers to new problems and challenges created by the ever-changing research environment. Finally, some guidelines and laws are currently being addressed in order to better serve the changing world of research, including issues such as cloning. Regardless of how ethical principles and frameworks have arrived, it is imperative for health leaders to be aware of the current environment and history of research ethics if the healthcare system is going to continue to be a ready and relevant force of community service and political direction in the future. This section discusses some of the philosophical viewpoints associated with ethical decision making. Understanding these values-driven apertures may assist you in your own decision-making process in future ethical

- 33. events where your individual judgment will have to be exercised. It is always prudent to remember that not all individuals exercise ethical decision making in the same way or consistently over time. In understanding both his or her own personality dynamic and the various apertures from which health professionals make decisions, the health leader will have an advantage in elucidating the dynamics of the patients and human resources in the organization. The philosophies or ethical frameworks discussed here are distributive justice, utilitarianism, egalitarianism, libertarianism, deontology, and pluralism. Distributive Justice At the foundation of ethics is distributive justice. This set of theories or ideologies attempts to instill a set of values, ideals of fairness based on those values, and beliefs in the allocation of resources (e.g., food, water, housing, wealth/money, opportunities, materials) throughout a society. At its roots, ethics is a framework that is based on a distributive justice theory or combination of those theories; ethics is an extension of resource allocation and the methods of that allocation, whereas morality or morals are the level of congruence to that ethical framework. “Principles of distributive justice are normative principles designed to guide the allocation of the benefits and burdens of economic activity.”33 Taken individually, distributive justice theories are neither right nor wrong in and of themselves. Instead, situations, contingencies, and values must be considered in the selection (creating an ethical framework) and application (level of morality) of the distribution of resources. Would the distribution of resources be the same in a mass-casualty situation in an emergency room, such as an influx of patients from a bus accident, as when conducting cholesterol checks at a health fair in the community? Of course not. The tough part of selecting an ethical framework based on values and beliefs and the application of that framework (morality) comes down to one simple truth: Resources are scarce in society, in health

- 34. organizations, in departments, in units, in families, and for individuals. Resource scarcity—the reality responsible for creation of disciplines such as economics, political science, and distributive justice/ethics—is the catalyst that requires a method for resource distribution. If all resources were abundant, how many conflicts, political maneuvers, or crimes would society have to deal with or resolve? Selection of a distributive justice theory based on the values and beliefs of a society, organization, group, or individual; developing an ethical framework from that theory; and applying that framework are responsible for some of the cultural conflicts, group tensions, and individual conflicts in the world, society, organization, or group. If two groups are strongly attached to their different ethical frameworks, resource distribution that fosters “fairness” for both groups can be difficult; that is one reason why negotiation is a valued skill. Lastly, avarice or greed may play into the scenario; scarcity can motivate greed and motivate competition. (In ancient Greece, avarice or greed was considered one of the seven deadly sins.) In health, social justice and market justice discussions are integrated as part of the selection of resource distribution mechanisms. Social justice advocates that: · [I]n a just society, minimal levels of basic needs like income, housing, education, and health should be provided to all citizens as fundamental rights. These basic needs are usually provided through various forms of social insurance; while market justice supports that the inexorable logic of supply and demand operating within the economic marketplace are key to determining the optimal outcomes of health care resources (with minimal or no intervention by government).34 These issues muddy the waters surrounding distribution of resources, especially in the health industry. Some of the well- known distributive justice theories are presented here in summary. What theories work best in health organizations? Does one theory fit all health situations?

- 35. Utilitarianism Utilitarianism, as a theory, aims to maximize the possible happiness of society as a whole. This goal requires that it be ascertained what makes every individual in that society happy and how to satisfy the greatest number of them. A policy that makes the highest number of people happy—or at dissatisfies the least—is the correct option to choose according to the dictates of this theory.35 Utilitarianism thus seeks to maximize utility (usefulness) from the distribution of resources in a society. This theory would balance social and market justice. Egalitarianism · Egalitarianism is a set of closely related theories that . . . advocate the thesis that all members of a society should have exactly equal amount of resources. Simpler theories of this kind are satisfied with the claim that everyone should be given, at all costs, completely equal quantities of certain crucial material goods, like money.36 John Rawls, in A Theory of Justice (1971),37 posited a supplementary position to egalitarianism known as the difference principle. In essence, egalitarianism negatively affects those who are less fortunate, such as the disabled and mentally challenged; based on this reality, more resources should be allocated to those who are less capable of performing productive work. This theory is more aligned with social justice. Libertarianism Libertarianism suggests that the market or market forces should determine the distribution of resources in a society. The Nobel Prize–winning economist Milton Friedman, who died in 2006 at the age of 94, was the best-known advocate on behalf of modern market forces as the key factors in an economy; he joined a long line of economists associated with this model, including the major historical figures Adam Smith and John Keynes. According to this perspective, market justice is the force that controls distribution. No pattern or criteria are important in the distribution of resources in a market-based approach; instead,

- 36. those persons who work diligently and intelligently should receive the fruits of their labor. Market justice is strongly associated with libertarianism. Deontology Deontology is the opposite of utilitarianism. It is an ethical framework and philosophy of resource allocation that suggests actions should be judged right or wrong based on their own values and principle-driven characteristics. Within this theory, there is no planning for the consequences of an action. As a result, the preponderance of the masses is not a major consideration, and the needs of the one can outweigh the needs of the many. In many ways, deontology is a case-by-case or individual-based framework for resource allocation considering the factors associated with that individual. Social and market justice are both considered valid considerations in this framework. Pluralism · Pluralists hold that goods which are normally distributed in any society are too different to be distributed according to only one criterion… To be just, a criterion which holds in one sphere should not be applied in another one. For instance, rewards and punishments should be distributed according to performance, jobs according to ability, political positions according to [election results], medical care according to needs, income according to success on the market, and the like.38 Both social and market justice are applicable in a pluralistic view. THE ETHICS OF HUMAN SUBJECT RESEARCH: A BRIEF HISTORY The ethical issues in human subject research have received increasing attention from health leaders over the last 50 years. Several ethical issues usually arise when designing research that will involve human beings. Among these are issues such as safety of the participant, informed consent, privacy, confidentiality, and adverse effects. Along with ethical issues, there are also ethical principles that govern research. Three

- 37. primary ethical principles, which are traditionally cited as originating in the Belmont Report, are autonomy, which deals with a participant making an informed decision regarding participation in a research study; beneficence, which refers to maximizing benefits and minimizing risk of harm to the individual; and justice, which demands equitable selection of participants and equality in distribution of benefits and burdens. Nuremberg Code: The history of research on unwilling and uninformed subjects is long and tragic. One of the main historical events that had an impact on establishing federal regulations for the protection of human research subjects was the Nuremberg Trial. This was the first high-profile case questioning of medical research. The trial occurred in 1949 when Adolph Hitler’s personal doctor, Karl Brandt, and 22 other doctors were accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity for conducting cruel and unusual experiments on Jews and other minorities. The Nuremberg Code, which emerged from the trial, emphasizes the importance of capacity to consent, freedom from coercion, and comprehension of the consequences of a person’s involvement in medical research (informed consent). Other provisions require the minimization of risk of harm, a favorable harm/benefit ratio, qualified investigators using appropriate research designs to answer questions, and freedom for the subject to withdraw at any time. The modern era of human subject protection is routinely dated from the promulgation of the Nuremberg Code. Its standards have been accepted and expanded upon by the international research community. Declaration of Helsinki: The World Medical Association (WMA) adopted the Declaration of Helsinki in June 1964. Its recommendations signaled the first efforts to attempt to distinguish between research that intended to directly benefit the volunteer clinically (therapeutic) and research whose primary purpose was to answer a scientific question (nontherapeutic). Emphasis was placed on the fiduciary relationship that exists between the physician and his or her

- 38. patients. “The Declaration of Geneva of the WMA binds the physician with the words, ‘The health of my patient will be my first consideration,’ and the International Code of Medical Ethics declares that, ‘A physician shall act only in the patient’s interest when providing medical care.’” According to the Declaration of Helsinki, all experimental procedures involving human subjects should be clearly formulated in an experimental protocol. The Belmont Report: Another regulation to protect human subjects was established in the United States by the National Research Act of 1974, which established the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research. The Commission issued the Belmont Report in 1978, which contained guidelines for the conduct of research based on the applied principles of autonomy (respect for persons), beneficence (maximize benefits/minimize harms), and justice (fairness in distribution). Human research ethics rests on these three basic principles that are considered the foundation of all regulations or guidelines governing research ethics. The Common Rule: In 1981, the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) published convergent regulations that were based on the Belmont principles. These mandated that members of an institutional review board (IRB) have broad backgrounds and include people who could represent community attitudes. Informed consent was required for research participants, and specific elements of information were required. The IRB is a review committee established to help protect the rights and welfare of human research subjects. Regulations require IRB review and approval for research involving human subjects if it is funded or regulated by the federal government. Most research institutions, professional organizations, and scholarly journals apply the same requirements to all human research. The jurisdiction of the IRBs includes the authority to review,

- 39. disapprove, or modify research as well as conduct reviews, observe/verify changes, and suspend or terminate approval. Societal Application of Distributive Justice Theories How does a society justly distribute resources? Resources include goods, materials, technologies, and funding/money—but also time and effort. As a health leader, the cost, quality, and access paradigm should be considered along with distributive justice considerations. Because health organizations are a scarce resource in a community, how resources are allocated and to whom are particularly salient issues and can be thorny points for health leaders. Does everyone get all the health services they need? How do you know? Does everyone get all of the services they want? How do you know? Has your organization done needs assessments and other analyses to determine these needs and wants? An example of the application of distributive justice theories can be found straight out the window of the health organization’s facility. Look at the parking lot. Parking in many places is a scarce resource. How are parking spaces allocated by your health organization, by your university or college, your clinic, your agency, or your association? In most health organizations, spots close to entries of the facility are reserved for disabled patrons, customers, patients and family members, and expecting or recent mothers (deontology); these are prime parking spaces that remain empty on many occasions. Other spaces may be reserved for surgeons, physicians, nurses, pharmacists, administrators, emergency room staff, and possibly others (utilitarianism) so that those professionals can get to work and start performing their various missions in the facility so as to do the greatest good, using scarce skills, for the greatest number of patients. Other spaces may be reserved by payment of a lease for the parking space (or valet parking) for those persons who do not want to hunt for a parking space (libertarianism); spaces more advantageous or closer to the facility usually cost more in terms of the monthly lease payment. The rest of the spaces are open on a first come, first

- 40. served basis, so that everyone has an equal chance at the space (egalitarianism). In the totality of the parking lot situation, pluralism is used to allocate this scarce resource. Thus distributive justice theories are the foundation of the ethical framework used to allocate parking spaces in a manner that society can justify within the norms and mores of that society. Surely you can see how resources are distributed in other areas of society and which distributive justice theory(ies) would apply to those areas. Selected Application of Philosophies Distributive justice theories can serve as ethical frameworks that may assist a health leader in framing his or her decision- making policies, systems, and processes. Two of these theories are presented in this section as contrasting frameworks for discussion: utilitarianism and deontology. Not all health organizations use only utilitarianism or deontological frameworks; for example, a health department’s immunization program most likely uses an egalitarian framework. Issues surrounding patient rights of autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice are addressed here as well. The selected ethical codes or frameworks should be integrated with the cost, quality, and access paradigm after considering any changes to the health system or resource allocation of health resources. Although these topics could take several chapters of discussion, we address them here for consistency and familiarization within the leadership framework. Health Leader Framework: Utilitarianism Utilitarianism is the view that an action is deemed morally acceptable because it produces the greatest balance of good over evil, taking into account all individuals affected. This theory posits that the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few. It also suggests that the end results and outcomes outweigh the process and the procedure used to reach those results and outcomes. The ultimate goal with utilitarianism is “mass happiness,” or the bringing of the greatest good to the preponderance of the people. Due to the end-results focus of

- 41. this methodology for decision making, the outcomes are often viewed as justifiable measures despite the consequences of the process. Under this perspective, the outcomes dictate the rules, and decisions are based on the predetermined desires of leaders.39,40 Medicare and Medicaid may be thought of as a utilitarian decision when the benefits were first introduced in 1963. The decision to redistribute the income of working persons in the United States by taking a certain percentage of every employee’s wages so that other certain individuals who were older than the age of 65 or who were indigent could receive subsidized care was initially (by many) seen as a socialist movement in the United States. The policy itself, almost by definition, provides for the greater good at the expense of others.41 These programs are different, however. Medicare is an entitlement program; most people have to pay into the program over time to become eligible for the program. In contrast, Medicaid is a welfare program, for which eligibility is based on various criteria and for which a citizen does not have to pay into to become eligible. From a macro view, however, both programs could be seen as utilitarian in nature. As the CEO of a health organization, you may someday be involved in a bond initiative where you lobby the county or local jurisdiction to increase local taxes in support of a new health venture in your local community. Your argument for this bond initiative may be based on a utilitarian effort.42 Health Leader Framework: Deontology Deontology is the opposite of utilitarianism. This ethical framework and philosophy suggests actions should be judged right or wrong based on their own values and principle-driven characteristics. Within this theory, there is no planning for the consequences of an action. As a result, the preponderance of the masses is not a major consideration in this theory, and the needs of the one can outweigh the needs of the many. This system of thought also focuses on personal responsibility and “what one ought to do.” According to this principle, the