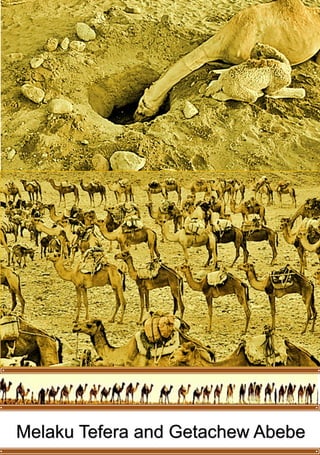

Camel in ethiopia

- 1. Melaku Tefera and Getachew Abebe

- 2. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 The Camel in Ethiopia 2012 Edited by: Melaku Tefera and Getachew Abebe Cover design: Melaku Tefera Layout: Melaku Tefera Production manager: Fisseha Abnet ______© Ethiopian Veterinary Association ISBN 9789994498192 All rights reserved

- 3. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012

- 4. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 PREFACE “Going lower to get higher” The pastoral regions of Ethiopia are traditionally lowland, namely those areas less than 1500 meters above sea level (masl). The most extreme of these is the Afar Triangle which at its lowest point is to 116m below sea level in temperatures range from 25°C in the rainy season to 45°C in the dry season. . It can be said that it is the opposite of the polar regions of our planet where only thermophilic species and life style can survive. The lowlanders are linked to the highlanders socially and economically via what is called the string of nature: water is discharged in the form of rain on the mountain roofs of Ethiopia and agriculturalists plow and cultivate cereals. Streams run to the lowland plains forming several perennial rivers which are the last refuge of pastoral people during the driest periods. The pastoral area of Ethiopia is the main camel belt in the horn of Africa. It is known by a camel culture, a monoculture which is expressed as adaptation to arid ecology through dependence on the camel which is based on uniform husbandry methods and mobility. The camel is the only large mammal capable of inhabiting the arid lowlands. Although official surveys estimate a total camel population of some two million head in Ethiopia this is most likely an under-estimate. The unique geographical, economic, social and cultural fabric of this biosphere is less known to the outside world even to many Ethiopians, as pastoralists were marginalized in the past. Furthermore, Ethiopia was considered as terra incognita vis a vis camel pastoralism and camel research. In this book we tried to distill the scattered and scanty literature on Ethiopian camel, the pastoralist, the environment, the market and camel health and welfare.We relied heavily on our experience of the past 25 years of on and off teaching and research on camels, blended with results and experience from other countries. The economic importance and adaptive value to climate change of the camel are on the rise which means that camels are considered as a priority for policy makers and researchers. Thus it is timely to compile such information in the form of book. Although camel production and health has, for the past last three decades, featured in the curricula of Ethiopian Veterinary and Agriculture colleges there has been no textbook on Ethiopian camels. This book is intended for undergraduate veterinary and animal science students, policy makers and researchers.

- 5. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 We are grateful to the following organizations organizations and all people who helped us in the preparation of this book, including FAO, for finacing the book project. The Ethiopian Veterinary Association (EVA) for coordinating and supervision of the project, Dr. Abrha Tesfay, Mr. Sirak Alemayehu for generously providing some of the photographs and those people who shared their photographs in public domain with no copyright restrictions, and Dr Peter Morehouse for taking his valuable time to go through all the cahapters of the book “If Mona Lisa is mysterious art then the camel is a mysterious creature” Melaku Tefera Associate Professor College of Veterinary Medicine, Haramaya University P.O.Box 144 Haramaya Campus. Ethiopia. 251-0914722459, < melaku22@yahoo.com > Getachew Abebe Professor, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

- 6. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 I FOREWORD The camel which is an economically, socially and environmentaly important animal is the least studied domestic species. The writing of such book is timely and will rekindle camel research in Ethiopia. Haramaya University being located at the pastoral and agropastoral interface has served as a brige between the highland and the lowlands research over the last 50 years. The camel research center at Babile and the Institute of Pastoral and Agropastoral at Haramaya University contributed to the meager research on the camel. This book is a culmination and milestone in camel research in endeavour Ethiopia. The camel as the bonanza of the drylands has an incomparable advantge compared with other livestock as it is the only livestock species capable of producing meat and milk when all other animals are limited by dehydration. Furthermore most of its products are nutritious, healthy and have medicinal value. This book attempts to create awareness of these aspects. Indigenous knowledge provides the basis for problem-solving strategies for local communities. The most important element to survive in the drlands is knowledge. A key factor is balancing livestock with the available plant biomass and moisture. The pastoralist experience of severlal millena is incorporated in this book. Intensification of camel production and advances are blended to encourage alternative techniques to extensionists, development professionals and researchers. The book, emphasizes on the importance of the camel husbandry in a holistic approach as a result it is of value to government bodies and policy makers in addressing climate change and sustainable livelihood. This book being the first on Ethiopian camels, is educative, informative and will inspire and guide young Ethiopians to pursue carrierrs on camel. “… one man camels safeguards for he owns them legally another man does so for the benefits he from them derives while a third man does so, too for the love he for the camel has…” (Somali oral tradition; Abokor, 1987) Professor Belay Kassa President, Haramaya University

- 7. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 I I CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION The dry land ecosystem Pastorlalism and pastoralists Camel pastoral tribes 1 CHAPTER TWO: CAMEL FEED, FEEDING AND NUTRITION Feed and Feeding of Camels Brows species of Camels Salt Lick and Water Resources and Management Watering 32 CHAPTER THREE: CAMEL BREEDS AND BREEDING Breeds Breed classification based on location Breed classification based on production performance Reproductive performance of male camel Reproductive performance of female camel 49 CHAPTER FOUR: CAMEL PRODUCTS AND PRODUCTIVITY Meat Milk Camel Hides Work Performance (pack and transport) 68 CHAPTER FIVE: CAMEL MARKETING AND ITS VALUE CHAIN Milk marketing Milk market value chain Structure of the livestock Supply markets Primary market Secondary market Terminal markets Live animal and meat export value chains 85 CHAPTER SIX : CAMEL WELFARE 110 CHAPTER 7: DISEASES OF CAMEL Bacterial diseases Viral diseases Parastic diseases Saddle soures and wounds 118 CAHPTER 8 :CAMEL RESEARCH AND THEWAY FORWARD 151 ANNEX 159 REFERENCES 169

- 8. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 1 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION Melaku Tefera, College of Veterinary Medicine, Haramaya University, P. O. Box 144, Haramaya Campus, Ethiopia, melaku22@yahoo.com he camel is a versatile animal; it can be milked, ridden, loaded, eaten, harnessed to plow or wagon, traded for goods or wives, exhibited in zoos or turned into sandals and camel hair coat (Faye, 1997). Despite the vital role of the camel in the arid zones its status vis a vis disease is not different from other domestic animals (Tefera, 1985).The camel in Ethiopia is not well studied. Camels are raised under traditional management systems details of which are not well documented. Pastoral camel production is under pressure because of multiple changes in the production environment (Scoones, 1994). Increasing human population pressure on pastoral grazing areas and the economic implications resulting from diseases and lack of veterinary services are some of the factors that adversely affect traditional camel production (Tefera, 2004). As camel owners become sedentary, the camel disappears. In many places of the world the development of infrastructure, especially roads, has caused the camel to lose its value as a riding animal or beast of burden. Despite the ecological, economical, environmental and social benefits of the camel it has remained the least studied domesticated animal (Payne, 1990). One reason is the main camel belt area is located in three poor countries, namely Ethiopia, Somalia, and Sudan accounting for 60% of the world camel population (Mukassa Mugerewa, 1981). The objective of this chapter is to document the origin distribution of the camel and to describe the habitat of the camel and the pastoralists in Ethiopia who look after them. 1.1.Origin and distribution of the camel All camels in Ethiopia are dromedaries (Camelus dromedarius). The history and origin of the domestic camel remain elusive when compared with those of cattle and small ruminants. A molar tooth and metatarsal bone was found by a team of Paleontological researchers in Ethiopia in the lower Omo valley, and these the fossils date from 2.6 million year ago (Pleistocene) and seem to be those of Bactrian camels. These are the first camel remains to be recognized in eastern Africa (Howell, et al. 1969). However during the Holocene period Bactrian camels became extinct in Africa (Kohler, 1993 cited by Getahun, 1998). The one-humped camel or dromedary is generally thought to have evolved from the two-humped Bactrian species. This theory is partly based on embryological evidence showing that during prenatal development the dromedary fetus actually has two humps De la Tour, 1971 (Cited by Mukasa Mugerwa, 1981) while a vestigial anterior hump is present in the adult. Williamson and Payne (1990) speculate that the one-humped species probably evolved in one of the hotter and more arid areas of western Asia. Dromedaries were probably domesticated in coastal settlements along the southern Arabian Peninsula somewhere between 3000 and 2500 BC (Wilson, T

- 9. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 2 1984). Once in Africa, Mikesell (1955) suggests that the camel spread west and southwards from Egypt, although Bulliet (1975) is of the view that the camels of the Horn of Africa are more likely to have come across the sea from the Arabian Peninsula than spread southwards from Egypt and Sudan. Curasson (1947) and Epstein (1971) indicate that the dromedary was introduced into North Africa (Egypt) from southwest Asia (Arabia and Persia). The camel was introduced into Ethiopia around 1000 BC. There are historical accounts describing the Queen of Sheba of the ancient Abyssinia kingdom at the head of a caravan of riches when she visited Israel's King Solomon and established trade in the Middle East. However, other reports suggest that camels were introduced into Eastern Ethiopia around 500 AD together with the introduction and spread of Islam. (Tefera, 2004). Archeological evidence shows that a camel tooth was discovered in Axum probable date 500 AD (Philipson, 1993). Cave Paintings of Lega–Oda near Diredawa presented as Figure 1.2, dated to the 1st centuary AD depict a camel. Thus the camels in North and Eastern Ethiopia appear to be distinct breeds and two routes of introduction were suggested as shown on Figure 1.3. Figure 1.1: Painting of Queen of Sheba and King Solomon The domestication of the dromedary, like many other domesticated mammals, has promoted unprecedented progress in cultural and economic development of human societies, representing a great leap forward for human civilization. Figure 1.2: Cave painting of camel at lega- oda, diredawa 1st century ad (Cervicek, 1971)

- 10. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 3 In Ethiopia camels were involved in the salt trade when salt blocks locally known as Amole were used as money in trading goods. All camel raising areas In Ethiopia have many similarities and one can conclude that it is a mono culture. 1.2 Abundance and distribution According to FAO (1979) statistics, there were about 17 million camels in the world, of which 12 million are found in Africa and 5 million in Asia. Of this estimated world population, 15.1 million are believed to be one-humped camels. There are 2 million camels in Ethiopia (CSA, 2009). Ownership varied from several hundreds, 50-100 and less 5-10 camels. Mostly in the large herds females were dominant 75%. Males were sold for as pack animals and meat. While in small herds mainly males were dominant in number and they were used for transport of goods. The distribution of the camel coincided with that of the drylands, and of T. evansi, and overlaps with the area occupied by Muslim societies as shown on Figure 1.4 A-D. In these areas there were no horses and mules. But in the south western lowlands there are no camels due to cyclically (tsetse) transmitted Trypanosomosis. There were four breeds: milk, meat, dual purpose and baggage camels. These were identified by their coat color conformation and production. Population growth was estimated (Tefera, 1985),using predictive formula: [Population growth estimate . Where A= % adult females above 4 years of age, B= % of infertile she camel, C= calving interval. D= survival rate of neonates and E=10% being the allowance for population mortality and slaughter. Figure 1.3: Origin and distribution of camels in Ethiopia (Tefera, unpublished)

- 11. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 4 In 1985, the camel herd was growing annually by 2.5 %. Taking the following parameters as determined in our study: e A= 60 %, B= 10% C= 2 years. D= 0.5 and E=10%. 1.3 The dryland ecosystem Ethiopia is topographically classified into two areas: highland and lowland. The periphery encircling the country generally consist of lowland plains, with an elevation below 1500 masl and mean annual rainfall below 500mm. The lowlands cover some 65 million hectares (61%) of the total area of Ethiopia and consist mainly of rangeland which is home to 12% of the human population and 26% of the livestock (Coppock, 1994). The climate in the lowlands is arid and, owing to the unreliable rainfall, the ecosystem in these environments never achieves equilibrium between grazing and fixed number of settled livestock. With increasing drought and erratic rainfall, cultivation of land is difficult and crop failure is common resulting in reduced per capita food production. Thus, traditional pastoralism constitutes the only efficient means of exploitation of the dryland resources (Payne 1990; Wilson 1984) otherwise heavy investment or irrigation and moisture harvesting technologies would be required. In the drylads where biomass is meager, resource utilization should be optimized through appropriate livestock production system (Njeuru, 1996). Multiple herd species have ecological and socioeconomic adaptive value, risk spreading and conservation of resources, identified as energy extraction pathways: a) the reliable pathway, shrub-camel-milk-human, b) the opportunistic pathway grass-cattle-milk- human and c) contingency, sale for cash pathway grass-small stock-meat-human as shown in Table 1.1. Camels cause less environmental harm compared to other livestock species (Schwartz and Dioli 1992). As climate change is drastically altering the global landscape, camels raising could become an alternative livelihood which is second to none. In Figure 1.4: Map of Ethiopia showing the peripheral lawlands ( a), distribution of camels ( b), muslim society (c) ,non existence of horses and trypanosoma evansi (d),(Tefera and Gebreab, 2001).

- 12. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 5 comparison to other livestock, camel production would appear insignificant, if viewed in isolation from the environment. Howevere camels can produce milk under very harsh conditions when and where other livestock species cease producing (Yagil, 1985). Most of the drylands in Ethiopia are range land and primarily arid and semi arid where other land uses such as agriculture is not economically feasible but it may also include areas that have in the past or could in the future be used for forestry. The environment is basic determinant of the nature and productivity of the range ecosystem. Physical environmental factors, which includes, climate, topography and soil determine the potential of the range land to support certain types and levels of land use hence in the following sections we will describe the dryland ecosystem in Ethiopia. 1.3.1 Temperature Except at high altitude temperature is seldom a limiting factor to plant growth. In the arid zones of Afar one of the hottest areas in the world mean annual maximum and mean annual minimum temperatures are 35 - 27°C respectively. The temperature on the hottest day reaches a maximum of 45°C. There is little variation in the temperature regime either seasonally or annually. 1.3.2 Evaporation Evaporative demand is another important environmental factor which determines range productivity. Water vapor is formed by evaporation (from solid surface such as water, soil, rocks and wet vegetation) and transpiration (mostly by plants). Evapotranspiration is the combined effects of these two processes. However, as actual evapotranspiration is often limited by the availability of water thepotential evapotranspiration, which reflects conditions where water is not limiting, is a better measure of evaporative demand on vegetation. In East Africa it is in the high range of over 150 - 250mm/year. This high evaporative demand is an important environmental factor for the region’s vegetation because the balance between it and rainfall is strong determinant of the amount of water that eventually becomes available for plant use. As with temperature, potential evapotranspiration varies little on an annual basis although the regional differences are marked. 1.3.3 Potential Evapotranspiration The ratio of annual rainfall to evapotranspiration p(R/Etp) is frequently used as indicator of relative aridity. Potential evapotranspiration is the amount of water vapor that would be transported into the atmosphere by evaporation and transpiration when water is freely available, as at the surface of the ocean. The greatest deficit between rainfall and evaporative demand occurs in eastern Ethiopia, Northern Somalia and Eastern Eritrea where rainfall is lowest and potential evapotranspiration is highest. The deficit is least in the highlands.

- 13. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 6 Table 1.1: Data on rainfall, evapotranspiration and aridity index for 250 stations in Ethiopia (Hawando, 1995) Figure 1.5: Dryland areas in Ethiopia delinated on bases of RR/PET ratio (Hawando, 1995) Figure 1.6: Distribution of rainfall seasons (Hurni, 1998)

- 14. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 7 Figure 1.7: Precipitation map of Ethiopia (CSA, 2009) Figure 1.8: Length of growing period in (CSA, 2009) Figure 1.9: Vegetation map of Ethiopia (Compiled from Mesfin Weldemariam, 1970 and Groombridge, 1992)

- 15. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 8 1.3.4 Rainfall Unlike temperature and potential evapotranspiration, rainfall shows considerable variability within the region in both space and time. Therefore it is closely associated with rangeland vegetation pattern. Rainfall is highest in the highland areas where up to 2000 mm/year of rain falls and lowest along the eastern border with 250 mm/year. Rainfall is highly seasonal and either unimodal or bimodal. The timing of the rainy season also varies. Mean annual rainfall is not considered in itself to be the best climatological indicator of the influence of rainfall on plant growth. Rainfall in eastern Africa is highly erratic and unreliable in terms of amount in- time and space. For instance Ellis, et al 1993 found annual rainfall to have varied from 85% to 12% of the long term mean over 63 years. Dry years were more common than wet periods. Arid regions differ from wet regions only in having more evapotranspiration per year. High intensity rainfall causes significant increase in surface runoff, which results in large amount of water becoming inaccessible to plants. The greater the loss by run off the less effective rainfall is in supporting plant growth. Tropical regions tend to have higher intensity rainfall than temperate regions. Rainfall events as high as 279-381 mm/day have been recorded in eastern Africa (Pratt and Gwynne, 1977). Minimal requirements regarding the amount of rainfall, the period of time over which it occurs and the ratio of rainfall to potential evapotranspiration must be met to initiate and maintain growth of range land plants. In order to initiate effective growth (of annual grasses) in arid areas a minimum of 15 mm of rainfall must fall within a week, the first rain must wet the seed for at least 3 days, and enough rain must fall to compensate for evaporation. However, under the high potential evapotraspiration typical of arid eastern Ethiopia, growth is still insignificant with rainfall of 25 mm over a 10 day period which exceeds a quarter of the potential evapotranspiration that is usually enough to initiate growth in semi arid range lands. King (1993) reported that, about 25 mm of precipitation is needed for growth of perennial grasses and shrubs and 40-60 mm for seed germination of annual grassland. 1.3.5 Soil Soils reflect the influence of climate, parent material, topography, time and living organisms (principally vegetation). The stronger influence of climate, in this case rainfall, is seen in the broad regional soil units of Eastern Africa. The specific nature of local soil types as reflected in their depth, horizonation, texture, color, fertility, etc which results from the degree to which the parent material, topography and time (in particular) combine to interact with and modify the effects of climate on soil development. Thus rangeland areas which share the same climate but which differ in terms of topography, underlying parent material or geological age are apt to have different soils.

- 16. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 9 Usually land units demonstrated by a particular kind of topography and or/parent material are smaller in area than those primarily due to regional climate. Therefore, soil units tend to be relatively small and thus have more a localized effect on the nature and distribution of vegetation. This is especially true in drier areas where rainfall and leaching, the major operational climatic factor in East Africa, are less influential. Even in those areas of eastern Africa where rainfall exceeds 1500 mm/year and climate is the overriding factor determining soil characteristics, the abundant latosols/red soils tend to differentiate locally into topographically related Catenas (associations of topographically differentiated soils). Soil fertility and available soil moisture are the major determinants of plant growth and production in tropical regions. Soil fertility is more likely to be the principal limiting factors in sub humid and humid regions because of the leaching effect of rainfall. In semiarid and arid regions available soil moisture is limiting factor. At lower rainfall soil parent material becomes an increasingly important influence on soil texture, structure and soil depth which are primary determinants of soil moisture availability to plant roots and there is strong correlation between soil texture and total soil nutrients. Sandy soils tend to be infertile and have very low water holding capacities, although at the same time virtually all water is available to plants. Thus sandy soils provide a better soil-moisture regime than clays. The deeper sandy soils tend to support more deep-rooted woody vegetation than herbs and grasses. Grass roots usually do not extend much beyond one meter in depth. Heavy textured clay soils hold more water than sandy soils but do not give it up to plant use as easily. They also tend to be more fertile and, when adequate moisture is available, produce more palatable and nutritious fodder. However, unpalatable and highly drought resistant grasses may also dominate clay soils. 1.3.6 Vegetation Rangeland vegetation not only changes over time but also strongly varies from one region to another. These differences, which reflect the influence of climate and soil, have important implications for potential rangeland production and therefore, for the management of rangeland resources. With increasing aridity (generally expressed by increasing temperatures, decreased rainfall and increasing number of dry months per year), grass height decreases, botanical composition changes, annual grasses replace perennial grasses in dominance and livestock and human carrying capacities decreases. Short annual grasses and mid-height perennial grasses dominate the arid and hyper-arid zones. Annuals dominate in areas where the original perennial grasses have been lost to drought. The nature of the vegetation is sometimes influenced by the predominance of certain types of soils. For instance, an abundance of sands, which improve the availability of soil moisture, allows the growth of perennial grasses in arid and hyper arid climates. Woody plants also abundant and important contributors to rangeland value. As rainfall decreases the probable physiognomic climax vegetation type becomes lower in height and more open. Across the same

- 17. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 10 rainfall gradient the major woody growth changes from tree to shrub to dwarf shrub. Forage produced by trees, shrubs and dwarf shrubs is especially important in arid and hyper-arid environments where herbaceous productivity is low and highly erratic 1.4 Geology of the Afar Depression The Afar Depression is an area of lowland plains dotted with shield volcanoes. It is cut by faults which separate areas of higher ground (or fault blocks) from the rest of the plain. It is bound to the west by the Ethiopian Plateau and escarpment, to the northeast by the Danakil block, to the southeast by the Ali-Sabieh block and to the south by the Somalian Plateau and escarpment. To the north, the southern Red Sea rift is extending down through the Gulf of Zula into the northern Afar Depression. To the east, the Gulf of Aden rift, is spreading through the Gulf of Tajura into the eastern Afar Depression, and to the southwest, extension continues through the Main Ethiopian Rift to the East African Rift System (Figure 1.10). Along the edges of the Afar Depression are large faults up to 60km long. These developed during the Oligo-Miocene (29-26 million years ago) as the Earth’s crust in the region began to be pulled apart by the movement of the plates. The faults led to the centre of the Depression dropping down relative to the Ethiopian and Somalian Plateaux and the formation of the rift valley. The area is now close to or, in parts, below sea level. Between about 6 and 7 million years ago, as the plates continued to separate and extension increased across the region, magma from deep in the Earth rose through the crust warming and weakening it. Movement on the border faults ceased, although they still command the landscape, and smaller faults developed along narrow bands in the centre of the rift valley. These narrow bands have continued to develop with thin vertical sheets of magma (dykes) being injected along them and erupting at the surface as volcanoes. In simple terms, a rift can be thought of as a fracture in the earth's surface that widens over time, or more technically, as an elongate basin bounded by opposed steeply dipping normal faults. Geologists are still debating exactly how rifting comes about, but the process is so well displayed in East Africa (Ethiopia-Kenya- Uganda-Tanzania) that geologists have attached a name to the new plate-to-be; the Nubian Plate makes up most of Africa, while the smaller plate that is pulling away has been named the Somalian Plate (Figure 1). These two plates are moving away from each other and also away from the Arabian plate to the north. The point where these three plates meet in the Afar region of Ethiopia forms what is called a triple-junction. However, all the rifting in East Africa is not confined to the

- 18. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 11 Horn of Africa; there is a lot of rifting activity further south as well, extending into Kenya and Tanzania and Great Lakes region of Africa. Figure 1.10 Rift segment names for the East African Rift System. Smaller segments are sometimes given their own names, and the names given to the main rift segments change depending on the source. (Makris & Ginzburg, 1987, Simon, 2010)

- 19. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 12 Summary Many arid and semi-arid grazing ecosystems are not at equilibrium and external factors (e.g. rainfall) determine livestock numbers and vegetation status. The productivity of rangelands is heterogeneous in space and variable overtime; therefore it is critical that the livestock movement must respond to spatial changes in feed availability. In uncertain environments fodder availability fluctuates widely over time and space. Grass production may range from zero to several tons per hectare, depending on rainfall. Such variation is spatially differentiated with same areas showing more stable patterns of primary production while others are highly unstable. Making use of such variable fodder resource requires tracking. Tracking involves the matching of available feed supply with animal numbers at a particular site. This is opportunistic management. Opportunistic management involves seizing opportunities when and where they exist and thus highly flexible and responsive. Effective tracking may be achieved in four ways: Increasing locally available fodder by importing feed from elsewhere or by enhancing fodder production, especially drought feed through investment in key resource site. Moving animals to areas where fodder is available, reducing animal feed intake during drought, reducing parasite burdens or breeding for animals with low basal metabolic (Larege animals) rates. Destocking animals through sales during drought and then restocking when fodder is available after drought. Ethiopia has sufficient water in the western part and rivers in the vast lands of the east, thus an alternative is the use of irrigated agriculture to boost crop or fodder production. However, most of the range land soil is salt affected, 11 million hectares of land in Ethiopia are salt affected (saline, saline sodic and sodic). The salt affected soils are a challenge to agricultural production. In the Middle Awash Valley eight years after an irrigation project was commenced salinity became very severe. Many productive agricultural lands were abandoned and became barren land due to lack of appropriate irrigation water management facilitated secondary salinization. The drylands are rich in energy sources such as uranium, oil, gas and geothermal power which are an as yet untapped potential treasure of wealth. Will these bonanzas sustain the camel to be the king of the desert?

- 20. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 13 1.5 Pastoralism and pastoralists / Biocultural diversity Pastoralism is defined as socioeconomic entity, which is based on subsistence production by making use of available rangeland resource through appropriate livestock production system identified as energy extraction pathways a) the reliable pathway represented by shrubs-camel-milk-human b) the opportunistic pathway grass-cattle-milk –human and c) the contingency pathway grass-small stock-market-human. Today there are three main livestock production systems in Ethiopia: a draught oriented system in the highlands, a milk oriented system in the lowlands (subsistence) and a minor commercial dairy system in periurban areas. However, farming systems are not static and change overtime and between locations owing to changes in resource availability and demand patterns. Traditionally the highlands and lowlands are linked economically in the form of trade. The highlands supply the cereal requirement of the pastoralists. In return the pastoralist supply livestock to the sedentary farmers, which they use them as plough oxen, see Figure 1 Figure 1.13 Livestock and cereal rotation in sedentary and pastoral interface In all pastoral systems the consumption of milk or blood seems to be most important diet although nowadays it is steadily dropping, and there are few, if any, which rely almost totally on milk or milk products. In some communities the reliance is still fairly high. The Borana of the southern rangelands of Ethiopia for

- 21. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 14 example, with some seasonal variations, still consume up to 59% of their diet as milk or milk products with the balance of the diet being increasingly made up of grain. For the Afar, milk probably constitutes less than 60% of total energy requirements, and grain again is increasingly the main food substitute. This increase of grain and decrease of milk consumption is in fact more and more the pattern in pastoral Africa. Nevertheless the African pastoralist is still firmly oriented towards a milk production mode as far as circumstances will allow and has not yet dramatically changed this in favor of selling meat or growing crops. Pastoralism relies on livestock diversity to exploit and make use of the diverse rangeland resources, and typical pastoral herds and flocks include grazing cattle, donkeys and sheep and browsing camels and goats. Pastoralism also relies on diverse livestock products including milk, hides, meat, blood and draft power. Camel pastoralism is most sustainable livestock production system in the drylands, as the dromedary is a livestock species uniquely adapted to hot and arid environments. It is also highly versatile; it produces milk, meat, and work, in an environment where no other livestock can survive. Camel pastoralists are those populations whose livelihood is based largely on camel production. Camel keeping is their major occupation although at times they diversify into keeping other livestock mainly sheep goat, cattle and sometimes engage in agricultural operations. Their vocation is suited to exploitation of natural resources. The main Ethnic groups and their herd composition are shown in Table 1.2 Table 1.2 Location and size of livestock in pastoral areas of Ethiopia (,000)* Pastoral region (Location in Ethiopia) Sheep Goat Cattle donkeys Camel Horses and mules 1 Afar (North Eastern ) 2000 3000 3600 200 900 0 2 Somali (Eastern) 6600 3300 5200 360 1100 0 3 Oromo/Borena (South Eastern) 1000 500 1400 60 530 0 Oromo/Kereyou(South Eastern) 200 300 300 20 10 0 4 Benshangul and Gambella ( western) 100 100 100 20 0 0 5 Southern nations and nationalities(Southern 340 500 450 40 0 0 6 Kunama (Northwestern) 100 150 200 10 0 0 * Central Statistical Agency, 2009 (population in thousands)

- 22. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 15 Figure1.14:CamelBeltareaofEthiopia(TeferaandGebreab2001)

- 23. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 16 Figure1.15MajorriverbasinsinEthiopia(UNOCHA-Ethiopia.2005)

- 24. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 17 1.6 Camel complex The camel is considered as a form of productive capital and also investment capital of herders. It is well known fact that livestock reproduce themselves even without market forces. The survival strategies of pure pastoralists are very much tied to the desire to reproduce and preserve the camel from which they also derive social capital. In the latter case, wealth and prestige are conceptualized with reference to camel. The camel herders are extremely affectionate to their camels expressed through a culture of complex customs which has developed as a form of ecological adaptation from an emotional attachment to the camel and expressed through affection and naming, collectively known as the camel complex. The Afar names each individual camel, and camels were involved in rituals such as birth. The Afar had a tradition called Budubta under which when a child is born it was given one female animal from each species. With good fortune the female animal will reproduce and become plenty. Apiece of the child’s umbilicus was put in small pocket and is tied to the neck of the animal as a talisman. The camel is also the store of value and the conventional medium for exchange of pastoralists’ bride wealth and payment. Camels are appreciated as dowry in marriage, and for social and religious ceremonies particularly during Eid al-Adha when camels are sacrificed. Camels are also used as compensation for crimes or inflicted wounds: if a young man is killed the cost is 20 camels, if an eye is wounded about two camels, each body part had a price and each crime had to be paid in terms of camels. Camels are never ridden, except by sick or tired women and children during migration. There are a number of sayings about the camel “A father without a camel is not a father”. Large number of camel stock signified high social status. Each pastoral group has its own territories. The Kunama reside in Tekeze valley, Irobe/Saho in Alitena valley, Raya –Kobo in Raya valley, the Afar in the Awash Valley, Somali in the Wabishebele valley and the Borena in Genalle valley. The Afars and Somalis are predominantly herders and are true pastoralists in the sense that they do not practice agriculture besides animals. 1.7 Risk spreading In the arid and semi arid lands crop farming through rain fed agriculture is unpredictable and least productive. In an effort to reduce risk pastoralist have developed various coping strategies. Herd diversification, involving multi species of livestock with different products, growth rate and functions allows exploitation of different niches. Mobility is a key strategy to the survival of pastoralists. With highly variable rainfall, the pastoral economy is typically of the “bust and boom” type. It booms when rainfall is plentiful and herds and flocks grow and are productive. It is bust when extended dry periods and drought occur. During this period livestock production and productivity rapidly decline to the extent of causing mortality. Local climatic, topographic, soil and vegetation variations necessitate the movement of people and livestock.

- 25. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 18 1.7.1 Conservation of resource In uncertain environments, livestock populations are limited by mortality associated with frequent droughts, disease and the like and cause degradation when purposely allowed to concentrate in one area. In order to minimize the risk of resource degradation pastoralists employ resource conservation strategies as listed below Traditional rotational uses of resource, allows regeneration of vegetation and avoids over utilization of the range lands. During feed scarcity in particular area, pastoralists keep livestock densities low by spreading out into other areas in order to avoid pressure on the grazing and water resources and pastoral traditional decision making processes reinforce regulation in determining the degree of concentration and dispersion of animals with respect to sustainable range resource utilization 1.7.2 Mobility Tracking rainfall, by moving herds oportunistically to follow the rains is a coping strategy of pastoralists to drought. Sometimes tracking rain-fed forage did not follow a regular pattern. For example the Afar pastoralists had a flexible migration pattern which could take the form of oscillatory type of movement up and down the Awash valley and into new territories in periods of severe drought. In the recent past many pastoralists became sedentarized either practicing farming, trade or taking employment thus breaking former traditional values as well as the value of the camel. Movement to key resources is also an option. During the dry season livestock concentrate around water points and during wet season they graze far from flooding rivers near to the permanent village sites. Figure 1.16: Altitudinal zonation of Livestock in East Africa (Gulliver, 1955)

- 26. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 19 Given altitude/rainfall correlation, pastoralists adjust their annual cycle to put herds in lowest (driest) part of range in the rainy season, gradually moving to higher elevations so as to end up at highest elevation at end of the dry season. Movement decisions are very complex, as they must plan for whole year but have many contingency plans, taking many variables into account; hence pastoralists have great need for up-to-date information. The information flow is channeled via kinship ties and sodalities (age-sets). Each household has large variety of stock, with minimal number of each (in traditional subsistence regime) being 25-30 cattle, 10 camels, 100 small stock (goats & sheep), and 10-12 donkeys (Note: household = women + children associated with a single adult male; homestead = group of related men + families). Each species has to be handled in certain way: e.g., cattle can be watered every other day, small stock need water every day, and camels every 3 days. Hence, in the dry season several herds and herding parties are required, which is a very labor intensive system. Table 1.3 Livestock movement pattern of Afar community Name of Zone/Sub zone Majour areas of mobility Wet season Dry season Drought time Zone 1: Dubti, Asayta and Afambo Subzones Doka: Chifra and Aura subzones between Hida and Uwa rivers Awassa: close to Awash river Close to Awash river Zone 2 Herders move eastwards in to Erebti and Afdera Woredas Retreat areas are in the eastern parts of Dalol, Koneba, Berehale, Aba-Ala and Megale subzones Zone 3 and 5 East and west of the Awash river south of the Kombolcha –Mile road Herders move east to Gewane and Alledege plains and west to the foothills below the Manin escarpment Most retreat areas are next to, or near to, the Awash river Amhara region (Cheffa valley) and Argoba Zone 4 and chifra Herders move eastwards into Teru and Aura subzones and the eastern parts of Yallo, Gulina, Ewa, Chifra and Mille Woredas Western parts of Yallo, Gulina, Ewa and Mille subzones Oromia Zone of Amhara region close to Awash river and Teru (Source: PFE, IIRR and DF. 2010)

- 27. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 20 Table 1.4: Wet and dry season grazing pattern in Somali Region Zone Wet Season Dry Season Gode Foot hills and uplands Along the Wabishebele river Afder Cheerti, Dolloban, Baren, Hargelle, Gorobagagsa Along Genale, Web, Wabishebelle rivers, El Har, Yabow, Dhan Adir, Shakissa, Budhi, Bali Baako, Qorsadula, Gerar Elgojo, Qundi, Goroba, Gagsa Fiq Qubi, Dooya, Dargamo, Qaruaqod and Maymuliqa Gebre Abood, Digiweyne, Jajale, Afmeer, Birqod, Malayko, Sulul, Ela Sibi, Qarri Deghabur Jig, Boholole, Dayr, Dig, Sibi Fafan, Jerer, Galaisha, Dakhata, Sibi Jijiga Babile, Gursum, Karamara Jerer, Fafan Dakhata Valley Qorehey Jool Jeeh, Nusdaaring, Handheer, Bank, Dhobweyn , Kalajeen, Hannan, Har-Ano, Jiracle, El-Ogaden, Melka Afweyn, Qorjeeh, Mario Ado, Elhaar, Banka Qoraheey, Banka Shaykosh Gabagabo, Mariaado, Subaarco, El Har, Giid, Guoglo, Subauke, Shey Hoosn, Alla Gadwene, Higloley, Quruh, Jeehdin, Herweyn Liben Ayinile, Gunway, Walenso, Moyale, Wayamo,Chianqo, Biyoley,Biyaoley, Boqolmayo, Triyangolo, Jarso Dhafabulaale extensive grazing areas far away from rivers birkas and ellas Seru, Sora, Dinbi, and along Dawa and Genale rivers Shinile Hils and uplands Araq, Bisiq, Muli, Qandaras, Erer river and Somaliland Warder Laheelow, Dhurwa, Hararaf, Aado,Qorile, Darafole, Markha, Lifo, Agaarweywe, Danod, Burawo and Las Anod in Somali land Wasdhug, Garlogubay, Yuub, Uband Taale, Warder, Galadi, Walwal (Source: PFE, IIRR and DF. 2010) 1.8 The dynamism of pastoralism Nintheenth century social evolutionists Morgan and Engles believed nomadic pastoralism was an evolutionary stage between foraging and settled agriculture. The current consensus is that pastoralists probably arose from marginalized surplus population of agriculturalists who for one reason or another lost their land base or abandoned farming and turned to full time herding Pastoralism is a dynamic system; pastoral societies pursue multiple resource economies in which the balance between pastoral and non pastoral activities is constantly changing in response to changing circumstances. The pastoralists do not by any chance discriminate against other forms of production. Based on their many years of experience they value livestock raising as the most valuable mode of

- 28. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 21 production. Otherwise the pastoralists do practice mixed socioeconomic (pastoral and off-pastoral, like trade etc.) changes that determine the growth or decline of the system. The impact of change on viability of camel raising within pastoral system is increasing its fragile or is destroyed it all together as the system itself is subject to pressure. Pastoralism is a subsistence system based primarily on domesticated animal production and excludes groups specializing in wild animals. The term subsisting is intended to exclude those who raise animals strictly for exchange value rather than direct consumption (e.g., commercial ranchers and dairy farmers, though as we will see most subsistence pastoralists rely on trade. Pastoralists can be categorized in terms of frequency of movement into three groups: a) Settled pastoralism: Animals are kept in one place most of all year b) Transhumance requires round trips from the home base to pastures on seasonal or emergency movements , without any major dwellings or barns in any location c) Nomadic: Moving herds to any available pasture, often on opportunistic basis over long distances with no fixed pattern 1.9 Pastoralists and climate change Droughts are inevitable in the drylands, they may occur frequently or less frequently depending on climatic conditions. Drought is one of the most limiting factors and a predicament for pastoralist communities. In order to understand how droughts affect pastoralism it is important to ask how pastoralists livelihoods are affected by drought? The most direct impact of a shortage in rainfall on pastoralist’s livelihood is the drying up of water sources and declining forage resources for livestock. Water and forage are the most important resources for pastoralism and changes in their availability greately influence livestock conditions, milk production and ultimately pastoralists’ livelihood. The experiences of major droughts during the last four decade in the horn of Africa show that pastoralists have been affected more than other groups. Climate variability is very high in the pastoral areas of this sub-region and often people have to cope with long periods without rainfall. Sommer 1998 argues that metrological drought cannot be avoided but its impact such as famine, disease outbreak and destitution can be greately influenced by timely and effective intervention. Droughts are not the only disaster that hit people in the drylands as conflict, disase and floods also create havoc. Disasters can be managed as the drought model shown in Figure 1:17 illustrates: A drought cycle consists of four stages: 1) Normal stage: Rainfall is adequate and there are no major problems. The danger of drought is always present and one should prepare for the worst.

- 29. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 22 During this normal stage pastoralists try to build up their herds, vary the composition of their herds, and build up social networks. Strong ties mean they can rely on others to help them during time of trouble. Crops can be grown to supplement their diet. 2) Alert or Alarm stage: The rains fail and the early signs of drought appear. During this time efforts concentrate on mitigating the effects of drought by migrating to distant grazing reserves, concentrating around water sources, selling extra animals, and giving gifts to relatives. 3) Emergency stage: Food and water run short causing severe malnutrition and high death toll of livestock and the peoples’ efforts shift to relief measures. At this stage people skip meals to reduce amount of food consumed, they harvest wild plants, hunt wild animals, sell fuel wood and appeal to government and donors for help. 4) Recovery stage: The rains return and people and animals can begin recovery. Reconstruction activities are set in motion. During this period they rebuild their herds. There is overlap between these stages. Some particularly vulunerable people feel the effects of drought sooner than others. Not all droughts go through all four stages. Adequate preparations during normal and alert stages may prevent the worst effect. Clearly, these droughts also affect natural resources. The amount of available food decreases and water points dry up. But in most of the drylands the vegetation shows a remarkable capacity for regeneration once rains return. Herds can build up rapidly by grazing on fresh vegetation. Pastoralist and crop farmers do different things at aach stage in the cycle and in different places. What they do depends on the availability of other sources of food and income, local traditions and the skills of individuals and households. In general pastoralism can respond more easily and quickly to drought than can crop farmers. They can buy or sell animals or move to new areas in search of water and grazing. Crop farmers are tied to their land and must wait for several months before crop is ready for harvesting.

- 30. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 23 Cereal price increase Livestock price fall Drought Forced to sell off livestock Smaller herd size unable to restock during recovery Abandon Pastoralism Figure 1.17: Extream consequence of climate change on pastoral livelihood 1.10 The camel people: clans and tribes A clan is a group of people related by blood and marriage and consists of a group of families of a patrilinear or matrilinear culture united by actual kinship and descent. Clan members may be organized around a founding member or apical ancestor. The kinship-based bonds may be symbolical, whereby the clan shares a "stipulated" common ancestor that is a symbol of the clan's unity. A tribe is a sociopolitical organization consisting of a number of families, clans, or other groups who share a common ancestry or perceived kinship descending from the same progenitor kept distinct culture, and also linked by social, economic, religious ideological belief. 1.10.1 Kunama The Kunama clan lives in north western Ethiopia around the town of Barentu and close to the border of Eritrea. The Kunama, thought to be among the aboriginal inhabitants of the region some are Christian, some Muslim, but many follow their own faith, centered on worship of the creator, and veneration of ancestral heroes. Their society is strongly egalitarian with distinctive matrilineal elements. The Kunama speak a Nilo-Saharan language unrelated to the dominant languages in Ethiopia and Eritrea. Formerly nomadic, today they are Agro-pastoralists whose cattle are also important sources of wealth and prestige. The Kunamas keep

- 31. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 24 camels which they ride and use as work animals in mills and for ploughing. Such traditional use is absent in the eastern part of Ethiopia. Figure 1.19 Kunama men Figure 1.18: Kunama women

- 32. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 25 Figure 1.20 Kunama women leading a camel

- 33. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 26 1.10.2 Irob The Irob people also spelled Erob are an ethnic group who occupy a predominantly highland, mountainous area in northeastern Tigray Region, Ethiopia. In general, the Irob are a bi-cultural community, they are Christians and Muslim. Their language is Saho and Tigrigna. The Irob economy is primarily based on agriculture, including animal husbandry. The region is also renowned for its excellent honey. Irobs raise camels; mainly male camel acquired from the Afar which they use in trade such as wood and charcoal. Figure 1.21 Irob town women

- 34. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 27 1.10. 3 Raya –Kobo The Raya Valley lies in Alamata, Raya Azebo and Hintalo Wajirat woredas in Tigray. It shares a border with Kobo of north Wollo to the south, Afar region to the east. The area is multicultural Christan and Muslim mix and the main languages are Tigrigna, Amharic and Afan oromo. The Raya -Kobo is known for cultivation of sorghum and teff. Other important economic activities in the zone are salt trading, cow’s milk and hiring of donkeys and camel for transport purposes. Camels generate income from transporting salt in Afar region. Figure 1.22 The people of Raya kobo 1.10.4 Afar The Afars are located in the East Ethiopia and in Djibouti, and Eritrea. Most of the Afars are nomads who herd composed of sheep, goats, cattle, and camels. A man's wealth is measured by the size of his herds. Meat and milk are the major components of the Afar diet. Milk is also an important social "offering", for instance, when aguest is given fresh warm milk to drink, the host is implying that he will provide immediate protection for the guest. Afar pastoral communities have indigenous institutions that govern the behaviour of each individual member. The traditional mutual support system is locally known as Hatota, which is practiced through clan ties. Afar society has its own information communication system, locally called Dagu system. The Dagu involves exchange of information

- 35. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 28 about daily life and general situations they observe, listen, or see on their ways or from their areas of residence or from markets. Figure 1.23 Afar man andFossil of Lucy Figure 1.24 Afar Girls and Boys

- 36. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 29 1.10.5 Somali Somali: are ethnic groups located in the Horn of Africa, also known as the Somali Peninsula. The Somalis speak the Somali language, which is part of the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic language family. Ethnic Somalis number around 15-17 million and are principally concentrated in Somalia (more than 9 million) and in Ethiopia (4.6 million) The name "Somali" is, derived from the words soo and maal, which together mean "go and milk" a reference to the ubiquitous pastoralism of the Somali people. Figure 1.25 Somali men and women 1.10.6 Borana The Borana or Borena are part of a very much larger group of the Oromo culture group. The Borana predominantly live in Ethiopia and Kenya. The economy and life style are organized around cattle, though the formerly taboo camels are becoming more important, and they now herd sheep and goats. Young men do the daily herding while the women do all family nurturing. The homestead groups may be required to move three or four times each year, often as far as 100 km, because of the low rainfall and poor land. Figure 1.26 Borana women

- 37. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 30 Figure 1.27 Borana man 1.10.7 Kereyou The Kereyou are pastoralist nomads. Their tribe plies the arid lands around the Awash River down in the rift valley for pasture for their cattle, goats and camels. Their range area is located in the rift valley and Eastern Showa areas. They are camel breeders, in addition they keep other livestock and recently they are shifting to cultivate cereals and vegetables. Figure 1.28 Kereyou man

- 38. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 31 Figure 1.30 Kerayou camel caravan

- 39. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 32 CHAPTER TWO: FEED, FEEDING AND NUTRITION OF CAMELS IN ETHIOPIA Gijs van’t Klooster1 , Solomon Nega1 and Melaku Tefera2 1 FAO Ethiopia, Addis Ababa 2 College of Veterinary Medicine, Haramaya University. P.O. Box 144 Haramaya Campus. Ethiopia. 251-0914722459, <melaku22@yahoo.com> ver large tracts of the Ethiopian rangelands, trees and shrubs are at least as important as grass forage, and over large areas provide the only feed for livestock. They are the dominant vegetation over vast areas of rangeland and support large livestock populations, especially of camel and goat, both of which are primarily browsers. Most likely due to the fact that camels are raised under traditional management systems, there is not much literature available about the feed, feeding and nutrition of camels in Ethiopia. Changing socio-economic and environmental conditions will lead to a change in pastoral production systems from mainly subsistence towards a more market orientated livestock production system and this will require an improved understanding of supplementary feeding This chapter provides an overview of the current knowledge on the quality of feeds selected by camels and feed preferences in order to understand the relationship between the forage availability and camel production. Understanding the browsing/grazing behavior of the camel, dietary preferences and their nutritive value together with a thorough knowledge of the environment is important to develop sound husbandry practices. Improved understanding may ultimately facilitate sustainable utilization of arid and semi-arid ecosystems. According to the pastoral area development study of 2004, browsing resources are under-exploited, leaving ample space for the further expansion of camel rearing. The study also mentioned that browsing animals have a much more environment- friendly impact than grazing animals like cattle, sheep and donkeys. 2.1 Feed and Feeding of Camels Camels are very versatile and opportunistic feeders, they accept a wide range of browse species that are often avoided by other species, but also some grasses. Foraging camels normally spread over a large area thus minimizing pressure on a particular area. Their long legs and neck enables them to browse up to 3-3.5m above the ground, a height that is not reached by other livestock. Due to their specific forage preferences and feeding at higher levels, camels are rarely in direct competition with other animals (notably cattle and sheep) for grazing and O

- 40. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 33 therefore a combination of these species results in increased productivity per unit of land. Some other adaptive features include the ability to select a high-quality diet that provides all the nutrients required by the body and the ability to survive on low quality fibrous roughages. They adapt well to different diets and dietary conditions. During the dry season, when other forages are scarce, camels can browse on the green tips of trees (e.g. Acacia sp.) that other livestock species do not, enabling them to survive droughts To avoid damaging the rangelands the Afar uses an elaborate herd splitting strategy (IIRR, 2004). Camel herds are split into five groups. Very young camels (dayna) are often kept in night camps and are handfed with browse, while the slightly older camels (neriga) browse nearby on their own. Older boys and girls herd the weaned camels (ekale) separately around the settlements. Lactating camels (homa): those normally herded by men (gudgudo) and those that are not herded but return to their settlement areas every night (areyu). Dry and pregnant female and male camels (adi galla) are herded by strong men the furthest away from settlements. After calving the lactating females are herded as homa. The location of the base camp and satellite herd depend on the availability of feed, water and labor. If drought is imminent, some of the base camp herd may be move to the satellite herd. A study conducted in Moyale, Kenya (Adan, 1995) shows that some of the specific Somali (Garri) camel herding and range management practices include rotational browsing, herd splitting, salt supplementation and watering. The Somali camel herders divide their grazing habitat into four micro-categories based on plant cover and soil type: i) thick bush, clay soil (Harqaan/gabiib), ii) thick bush, black soil (agricultural Adable/dhoobey), iii) open bush, red soil with good water conservation (dooy) and iv) open bush, mixed grey and red soil (Bay) The intimate knowledge of the environment common to many of the pastoralists allows a great flexibility in decision-making and enhanced ability to utilize all resources available (Farah et al., 1996). The present study reveals that the Somali camel herders of Moyale (Kenya) District adopt herd splitting as a risk spreading strategy. They split their herds into home-based herds (usually lactating) and nomadic herds (mostly dry). Home-based herds were kept close to settlements with possible deficiency in forage supply, whereas nomadic herds utilized better distant pastures. Herd splitting aims at reducing competition for forage and water resources between herds, thereby optimizing pasture utilization. The strategy appears to be a desirable and realistic attempt to utilize range resources more

- 41. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 34 evenly while maintaining the productivity of the animals. The strategy also guarantees continued provision of milk for settled families. When surplus milk is available, it is sold in settlements to provide cash income for other family needs. Thus, the strategy responds to both the needs of the camel and those of the family. In this way the management of the herd ensures a sustainable flow of benefits from the camels to the households while coping with production constraints. A study on the behavioral preference and quality selected forage by camels (Dereje, 2005.) was conducted in the Erer valley of Somali region, with an altitude of between 1300 and 1600m above sea level, to determine the behavior, dietary preference and forage quality of free ranging dromedary. The vegetation cover includes dwarf shrubs such as Indigofera species, large shrubs and trees such as Acacia and Boscia species and is also highly populated by cacti. The annual precipitation is between 400-500mm. The study was conducted both in the dry and wet season and for different age and sex groups, i.e. young female, young male, adult males and adult females. Browsing and grazing was the dominant activity during the day (about 65% of the 10.5 to 12.5 hours per day they are outside the corral) in both seasons. During the dry season the time devoted to browsing was significantly longer and in general young animals spent more time browsing than adults. The study also looked at the browsing preference of camels both in the dry and wet season. The camels selected a total of 21 species of plants in the dry season and 30 in the wet season. On average 79 and 83 percent of the camel’s diet was comprised of perennial woody plants in the dry and wet season respectively. The difference in behavioral activities within seasons seemed to be attributed to age differences. Young camels, especially in the dry season, were observed facing difficulties eating thorny plants such as Opunta and dry twigs, which leads them to spend more time on selecting smaller and more delicate parts of plants to meet their nutritional requirements. Camels were also seen to favor flowers and fruits when available. It was also observed that camels did not eat from a single plant for a long time; instead they moved around and took small portions from each plant, causing a low browsing pressure on each plant. The researchers recorded the ten most preferred plant species that occupied 87 percent and 80 percent of the total feeding time in the dry and wet season respectively (Table 2.1.). Opuntia (18 percent) was the highest ranked plant in the dry season, while Acacia brevispica (22 percent) was the highest ranked plant in the wet season. The high water content of Opuntia may be the reason for its

- 42. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 35 popularity in the dry season. The A. brevispica had the highest CP content, both in the wet and dry season. Table 2.1 Forage plant species preferred by dromedary camels during the dry and wet seasons. Vernacular name (Somali) Scientific name Proportion of time spent feeding Category Dry season Tin Opuntia sp. 0.18 Shrub Iswadh Acacia brevispica 0.15 Tree Qudaahtol Plepharis Sponisa 0.11 Herb Gidirmaan Indigofera oblongifolia 0.09 Vine Timirlog Canthium bogosensis 0.07 Shrub Adaad Acacia Senegal 0.06 Shrub Keddi Balanitus Aegyptiaca 0.06 Tree Qalqalcha Boscia angustifolia 0.06 Tree Dhigrii Becium filamentosum 0.05 Shrub Dhigriaas Becium sp. 0.05 Shrub Merodimakaraan Acacia sp. 0.02 Shrub Kalijog 0.02 Tree Anannoo Euphorbia tirucalli 0.01 Shrub Eriaad 0.01 Shrub Others, unidentified. 0.01 Mixed Karfaaweyn Lantana camara 0.01 Shrub Je’ee Boscia cariaca 0.01 Shrub Kediqus Balanitus glabra 0.01 Tree Eriqurn Vepris glomerata 0.01 Shrub Warsaames Dichrostochys cinerea 0.01 Shrub Awus Mixed grass sp 0.01 Grass Wet Season Iswadh Acacia brevispica 0.22 Tree Qudaahtol Plepharis Sponisa 0.12 Herb Galol Acacia bussei 0.09 Tree Midhayoo Acacia melifera 0.08 Tree Adaad Acacia Senegal 0.06 Shrub Gob Ziziphus 0.05 Tree

- 43. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 36 mauritanea Dhabi Grewia tembensis 0.05 Tree Tin Opuntia sp. 0.04 Shrub Maran Caucanthus edulis 0.04 Tree Gidirmaan Indigofera oblongifolia 0.04 Vine Others, unidentified. 0.02 Mixed Keddi Balanitus Aegyptiaca 0.02 Tree Je’ee Boscia cariaca 0.02 Tree Eriqurn Vepris glomerata 0.01 Shrub Qalqalcha Boscia angustifolia 0.01 Tree Dhigrii Becium filamentosum 0.01 Shrub Merodimakaraan Acacia sp. 0.01 Shrub Anannoo Euphorbia tirucalli 0.01 Shrub Awus Mixed grass sp 0.01 Grass Cekaa Calpurnia aurea 0.01 Shrub Kabbaw Commiphora africana 0.01 Tree Futawadher 0.01 Shrub Timirlog Canthium bogosensis 0.01 Shrub Hiil Vernonia cinerances 0.01 Shrub Warsaames Dichrostochys cinaerea 0.01 Shrub Kalojog 0.004 Tree Qarfaawein Lantana camara 0.004 Shrub Kediqus Balanitus glabra 0.004 Tree Dhigriaas Becium sp. 0.004 Shrub Eriaad 0.003 Shrub (Adopted from Dereje, 2005) Another publication (IIRR. 2004) mentioned common native trees in pastoral rangelands that are useful to the pastoralists, these include: Acacia bussei, Acacia millifera, Acacia seyal, Acacia tortilis, Balanites spp., Commiphora spp., Euclea shimperi, Gewia tembensii and Grevia bicolor. The livestock master plan study mentions the species mentioned below as major browse species (Kuchar et al. 1995a). Camel feed is almost all browse: browse

- 44. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 37 provides 95-99% in dry season, 90-97 in wet season. The rest is grazing, except in dry season, fallow and residues each contribute 0.5%. Acacia senegal, depending on soils and rainfall varies from a bush to a 10m high tree, especially if heavily browsed by camels becomes a dwarf tree. Cactus (Opuntia), O. ficusindica is especially in the dry season regarded outstanding dry- season camel fodder by the Somali. Cordia sinensis was rated by camel owners the no.2 camel browse in Turkana District of Kenya. Probably all Acacia spp. are browsed at one time or other by stock; Studies have found, however, that in some regions even the camel, an animal with a reputation for eating almost any plant, will shun some acacias. In Ethiopia, the species most valuable for livestock are A. nilotica, A. senegal, A. seyal, A. sieberiana, A. tortilis and perhaps A. mellifera and Faidherbia albida. All have palatable browse and moreover nutritious pods that can be very important for camels. Singled out as preferred or important camel food in the literature are A. drepanolobium, A. oerfota and perhaps A. reficiens. In NE Ethiopia, Kahurananga (n.d.) found that acacias formed the largest part of the camel diet; all species were browsed but the most important were A. asak, A. mellifera, A. oerfota and A. Senegal, and A. tortilis pods were considered excellent in camel milk production. The importance of A. tortilis as a forage resource has been recognized by the Southern Ranehland Development Unit (SORDU) project, and it encourages multiplication, and fencing of seedlings. Studies in the Borana rangelands indicated that there are about 15 woody plant spp considered to be encroachers (OWWDSE, 2010). The major spp include Commiphora afiricana, Acacia brevispica, Acacia nilotica, Acacia drepanolobium, Acacia bussei and Acacia horida. A recent estimate indicated that about 52% of the Borana rangeland is encroached by bushes and shrubs (Gemedo, 2004). Livestock diet and palatability studies have recognized the importance of commiphoras in camel and goat diets. The majority of the rangeland Burseraceae is palatable to especially camel and shoats, even some of the sap-spraying species appear to be good browse. Another obviously hedged species in this section is C. truncata. It is an outstanding browse, the no.1 camel food plant according to some Somali pastoralists. C. sphaerophylla (sec. Hemprichia) with its distinctly sweet-smelling sap is almost its equal. Many members of sec. Opobalsameae are highly rated but exhibit little or no browse impact. Among the boswellias, B. microphylla and B. neglecta, both relatively large trees, are palatable and outstanding feed sources for camel.

- 45. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 38 According to the pastoral area development study of 2004, browsing resources are under-exploited, leaving ample space for the further expansion of camel rearing. The study also mentioned that browsing animals have a much more environment- friendly impact than grazing animals like cattle, sheep and donkeys. Acacia brevispica: a Weed or a Browse? Browse: Although called a common encroacher in a southern Ethiopia rangeland study (GRM 1989), Acacia brevispica is regarded as an outstanding browse of livestock in another study conducted in southern Ethiopia (Woodward & Coppock 1995), particularly in the wet season when it constitutes 76% of the camel’s diet, 56% of the goat’s and 23% of the sheep’s; also a major dry-season browse of camel (22%) and goat (30%) though apparently not browsed by sheep in the dry season. This is in line with the study done by Dereje, M., 2005, that found Acacia brevispica was the number one browse in the wet and the number two browse in the dry season. Weed: Impenetrable Acacia brevispica thickets of this prickly shrub have replaced normal evergreen bush land toward its lower altitudinal limits in Samburu District, Kenya (FAO 1970). It forms fast-growing thickets difficult to eradicate (Pratt & Gwynne 1977), and considered one of the most undesirable components of thickets that have invaded woodland (Thomas & Pratt 1967). When cut or burnt it regenerates more rapidly than any other acacia and can easily produce 2 m of growth in one season. "It is perhaps the most difficult of our acacias to eradicate." (Bogdan & Pratt 1974) In his book on East African weeds, Ivens (1968) singles out this plant as the worst of the acacias as a bush-encroachment species. Pratt & Gwynne (1977) rank it among the 4 most troublesome woody species in East African rangelands. The study on the behavioral preference and quality of selected forage by camels (Moges, 2005) also collected feed samples of the ten most preferred species (Table 2.2.) in the dry season as well as the wet season were collected, dried and analyzed using standard methods. All chemically analyzed samples had relatively high crude protein levels. In both seasons, based on analysis of the ten most

- 46. Camel in Ethiopia - 2012 39 consumed plants, the average diet consisted of 170g CP/kg dry matter, which is similar to the amount required by high producing dairy cows. The range and composition of the ten most preferred species (g/kg dry matter (DM)) were for crude protein (CP) 88-228, P 1.3-3.3, Ca 12-48, soluble tannins 29-216 and condensed tannins 9.4-129 absorbance unit/g. In vitro dry matter digestibility (IVDMD) varied between 0.41 and 0.65. The Ca: P ratios in the plant species are all very high, ranging from 6 to 16 in the dry season and from 4 to 29g/kg DM in the wet season. Based on the chemical analysis A. brevispica has the highest CP level in both seasons, while Opuntia has the highest IVDMD level in both seasons. The results also indicate the high level of tolerance of camels to the ingestion of tanniniferous plants 2.2 Feeding of Camels Lactating dromedary camels on range in the Erer valley of eastern Ethiopia substantially increased milk yield when supplemented with protein or energy feeds (Dereje, 2005). Their experiment revealed that camels showed a good response to supplementation with both CP (groundnut cake) and energy (maize), but with a higher response to protein. Feeding 4kg of groundnut cake daily per head improved not only the milk yield, but also the net income by 88% in the dry season and 71% in the wet season. A higher milk yield could reduce the competition between the calves and the family for milk and thus increase calf survival. In turn this will have a positive effect on overall herd productivity. Oil seed by-products in the region may thus have an important role to play in improving the economic base of sedentary camel herders. It is well known that anti-nutritional factors such as tannins from range plants have a negative effect on nutrient availability, particular proteins (Kumar and Vaithiyanathan, 1990) and therefore in this experiment it is possible that there was a substantial increase in amino-acid uptake by the camels from protein supplementation (groundnut cake).

- 47. Camel in Ethiopia – 2012 40 Table 2.2: Composition (g/kg dry matter) and in vitro dry matter digestibility of the ten most preferred plant species by camels Tc= tannins condensed ts = tanisis soluble Vernacular name (Somali) Scientific name DM Ash OM CP P Ca IVDMD TS TC Dry season Tin Opuntia sp. 213 173 827 133 2.6 38 0.654 144 9.4 Iswadh Acacia brevispica 725 80 920 214 2.3 21 0.486 110 28.9 Qudaahtol Plepharis Sponisa 777 127 873 126 2.4 39 0.453 55 13.8 Gidirmaan Indigofera oblongifolia 207 157 843 150 2.1 28 0.498 51 12.7 Timirlog Canthium bogosensis 666 72 928 165 2.2 18 0.469 146 83.1 Adaad Acacia Senegal 517 111 889 191 2.2 25 0.491 80 22.2 Keddi Balanitus Aegyptiaca 263 81 919 200 2.4 15 0.497 78 17.7 Qalqalcha Boscia angustifolia 405 115 885 206 2.4 22 0.507 110 22.7 Dhigrii Becium filamentosum 646 86 914 160 2.6 25 0.457 113 30.8 Dhigriaas Becium sp. 713 80 920 165 2.4 25 0.450 110 26.7 Dry season Iswadh Acacia brevispica 420 77 923 228 2.3 23 0.512 128 29.9 Qudaahtol Plepharis Sponisa 256 153 847 131 1.6 46 0.484 46 14.8 Galol Acacia bussei 344 65 935 199 2.4 12 0.481 216 56.9 Midhayoo Acacia melifera 261 70 930 116 1.7 21 0.467 76 29.2 Adaad Acacia Senegal 374 58 942 180 2.1 14 0.538 147 27.4 Gob Ziziphus mauritanea 172 64 936 189 3.3 14 0.599 44 39.2 Dhabi Grewia tembensis 386 91 909 171 2.1 26 0.491 178 129.0 Tin Opuntia sp. 72 155 845 88 2.4 32 0.619 119 22.8 Maran Caucanthus edulis 401 79 921 201 1.3 27 0.408 138 38.4 Gidirmaan Indigofera oblongifolia 138 198 802 218 2.4 48 0.610 29 11.4

- 48. Camel in Ethiopia – 2012 41 DM: dry matter, OM: organic matter, CP crude protein, IVDMD: In vitro dry matter digestibility, Tannins condensed: absorbance units/g dry matter. Table adopted from M. Dereje, P.Uden / animal feed science and technology 121 (2005) 297-308. Table 2.3 Effects of supplement treatment and season on milk yield and milk composition and economic evaluation of diet supplementation. Dry Season Wet Season Contro l Energy supplemen t Protein supplemen t Contro l Energy supplemen t Protein supplemen t Production Milk (kg/Day) 6.9 8.6 12.2 8.2 9.5 13.6 Fat (g/l) 36 37 39 38 37 39 Protein (g/l) 26 27 26 28 27 28 Economic evaluation Costs Supplement s n/a 6.2 3.4 n/a 6.2 3.4 Other/dc 6 6 6 6 6 6 Income Milk 17.25 21.5 30.5 16.4 19.0 27.2 Net 11.25 9.3 21.1 10.4 6.8 17.8 2.3 Salt Lick and Water Resources and Management In traditional systems the only supplement provided by the herders is a salt. It could be common salt (NaCl) or a particular type of soil dug from a specific location. Camels also forage on salty plants or are watered from salty wells if available. Camels have a higher salt requirement than other livestock (Wilson, 1994). Supplementation is in the form of mineral salt, or allowing grazing on salty grasses on saline soils for at least 5 days. Many Ethiopian Somalis offer ½ kg table salt per head at 2 month intervals especially during wet season. In general, ruminants in tropical regions do not receive mineral supplements other than ordinary common salt (sodium chloride), but depend on pastures for their mineral needs (Mcdowell et al., 1995). The observation of Macdowell (1995) that such animals consume a considerable amount of earth was confirmed by the present study. However, the mineral contents in soils are highly variable. The

- 49. Camel in Ethiopia – 2012 42 importance of salt for camels is common knowledge among camel herders. In the study area, camels depend on salt plants (halophytes), salty soils (kuro) and sometimes commercial salt supplements for their mineral needs. Most herders (70%) claim to follow a regular deficiency preventive routine. Camels kept in the home-based herd were more frequently supplemented with purchased salt. This was attributed to the fact that they had limited access to distant grazing areas with salt plants. “Salt deficiency symptoms” revealed by the herders included chewing bones, eating soils from anthills, reduced milk yield, reduced water intake, and increased straying in search of salty plants. Periodic salt supplementation was reportedly done once or twice a year in Somalia (Elmi, 1989) and six to seven times in Kenya (Ayuko, 1985). Mineral deficiency can cause a high susceptibility to skin disease (Dioli and Stimmelmayr, 1992; Bornstein, 1995) and consequently affects production. In addition, there are risks of loss or predation when animals stray or break out of night enclosures in search of salty plants. Camels manifesting bone chewing (pica), an indication of poor mineral nutrition, was reported by 98% of the respondents. Further, 81% of the respondents claimed to have seen their calves born with bent or weak legs, which recovered later in life. A possible reason for the calf-hood defects is the insufficient concentration of calcium and phosphorus in the bone matrices (rickets) in calves from deficient dams. This suggests that mineral deficiency is widespread, posing constraints to the performance of camels. In the Afar Aba-Ala there is salt feeding proactice to lactating camels. The camels respond to salt feeding calls from about 500 meters, they voraciously consume the salt each camel was supplemented about 100g/camel/ day. Also seasonally camels were sent to a place called Dergha a sort of special soil where animals were able to lick mineral on voluntary basis. Its content was not dermined. Salt supplementation was known to increase milk production. Sodium facilitates the absorbtion of propionate a precursor of lactose in the rumen and also increases water intake which inturn increases milk yield. Animals had access to water based on groups, pregnant camels and males were watered every eight days. Lactating came every other day and those at the end of lactation everty 5 days. 2.4 Water supply to camels Water is by far the most important nutrient and an indispensable necessity for the camel and livestock. The camel is highly resistant to water deprivation it can loose upto 20% of its body weight and drink upto 200 liters in 20 min. However, the ablity of the camel to withsand water deprivation should not be over exploited for production puropses. It is necessity and must be provided on daily basis if water is