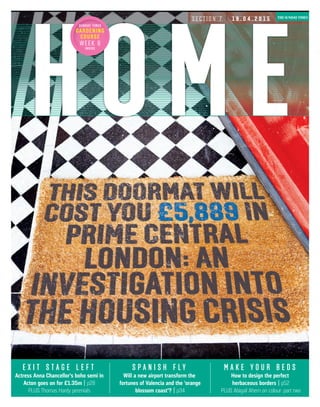

Home truths: Sunday Times housing crisis investigation

- 1. S P A N I S H F L Y Will a new airport transform the fortunes of Valencia and the ‘orange blossom coast’? | p34 M A K E Y O U R B E D S How to design the perfect herbaceous borders | p52 PLUS Abigail Ahern on colour: part two E X I T S T A G E L E F T Actress Anna Chancellor’s boho semi in Acton goes on for £1.35m | p28 PLUS Thomas Hardy perenials S E C T I O N 7 1 9 . 0 4 . 2 0 1 5 HOMEHOME SUNDAY TIMES GARDENING COURSE WEEK 6 INSIDE

- 2. 19.04.2015 / 13 SUNDAY TIMES DIGITAL Confused by the housing crisis? Watch a 90-second video guide on tablet and at thesundaytimes.co.uk/homevideo Ask Dame Kate Barker what her housing crisis looks like, and she tells you: “My younger son is homeless.” Like more than 3m parents across Britain, the economist, who blew the whistle on the country’s house-building shortage more than a decade ago, now has a boomerang child at home — her 24-year-old graduate son earns too little to rent. Ever since Barker’s influential government review of 2004, the term housing crisis has remained in the headlines — and been the subject of kitchen supper parties in the suburbs. In the 20th century, people fought for equal rights, gay rights, animal rights. In the 21st century, housing rights have hit the streets. It is now the subject of mass rallies in Westminster, celebrity-led crusades against redevelopment and even protests against rising property prices at a Foxtons branch in London. Every week brings new figures: the average age of a first-time buyer in the capital is now 37, yet some banks have started to reject mortgage applications from those in their forties. More than 10,000 streets now boast an average house price of £1m, but the number of 55- to 64-year-olds taking in lodgers has soared by 75% in the past two years according to research from SpareRoom.co.uk. There are an estimated 610,000 empty homes in England, but 2,714 people slept rough on any one night last year. What does it all mean? Is it really a crisis that a 26-year-old can’t buy their first home in their preferred location, that a mortgage-free baby gloomer can’t sell their main asset for as much as they’d like or a multimillionaire has to pay a mansion tax? You might argue not, and a lot of people have done very well from bricks and mortar, but that doesn’t mean there isn’t a problem — and it’s beginning to affect all of us. In London, business leaders surveyed by KPMG for the CBI named housing as one of the biggest threats to competitiveness, and Mark Carney, the governor of the Bank of England, has called the housing shortage and the resulting distorted market “the biggest risk to financial stability, and therefore to the durability of the [economic] expansion”. There is a shortage of about 2m homes across Britain — following more than 30 years of building far too few — and it affects everyone. The backlog has pushed up house prices at a rate that, if applied to food since 1971, would see us fork out £54.56 for a 2.5kg chicken, according to the charity Shelter. It is no longer about the 1.4m people on social housing waiting lists; now owners of multimillion-pound empty nests worry about where their children will live. “Everybody under the age of 40 has some kind of housing problem: they can’t buy or can’t move,” says Lord Best, an independent peer and chairman of the all-party parliamentary group on housing. “The older generation has done very nicely, but it hits you in the pocket as well when your children or grandchildren need large sums from you.” ANATOMY OF A CRISIS Exclusive research by Hamptons International for Home has revealed the full extent of the property generation gap across almost 3,000 postcode districts in today’s money. At present, the average household, which means a £40,000 income, could afford a small two-bedroom flat with 643 sq ft of living space. In 1975, that household would have been able to buy a three-bedroom house more than a third bigger at 1,024 sq ft. Of course, the gap manifests itself in more ways than simply how much space you can buy, says Johnny Morris, head of research at Hamptons. “For millennials [born between 1980 and 2000], many simply can’t afford to buy, having to rent long-term or live at home with their parents. Others will compromise on location, space and quality of property.” The gap between the have-properties and the have-nots is widening. Almost half (48%) of households aged 25 to 34 rented privately in the year to March — more than doubling in the past decade to 1.6m, according to the English Housing Survey. Meanwhile those who own their homes outright overtook those with a mortgage last year, driven by a 38% rise in outright ownership among over-65s since 2004. The Hamptons data, which takes into account how the value of money has changed because of inflation and mortgage affordability rules, pinpoints the areas with the biggest gulfs: E8 in Hackney, east London, tops the chart with 441% real price growth. A £40,000 income would now buy you a 293 sq ft studio there, compared with a 940 sq ft, three-bedroom terraced house in 1975. That skyrocketing growth has enabled Richard Blanco to amass a buy-to-let portfolio of 13 properties across London and Nottinghamshire on the back of a two-bedroom flat in E8 that he bought as a twentysomething in 1995. (It’s still his home.) “It was partly luck. I wanted to buy in Clerkenwell or Islington, but couldn’t afford it, so, reluctantly, moved to Hackney. Of course it grew on me and now I love it,” he says. In 2003, he remortgaged his flat to buy another just like it around the corner, starting a career. He is now a representative for the National Landlords Association. On the flipside are millennials such as Heather Elliott, a graphic designer, 26, who rents in a six-bedroom Victorian house in the borough with six other media and design types, all under 29, for £3,600 a month. “I’d love to buy, but it’s a million miles away. At least I’m managing to save because there are so many of us to share the costs.” If they have a repeat of their 5% rent rise last year, however, several housemates will be priced out. Outside London, Brighton (240%), Bristol (174%) and Bath (164%) have the biggest property-generation gaps. Yet in a reminder that Britain’s housing market is far from uniform, real prices fell in four areas, all in the north: Hull (-14%), Hartlepool (-8%), Middlesbrough (-2%) and Grimsby (-1%). At the extreme, Home A SPACE THE SIZE OF THIS PAGE IN PRIME CENTRAL LONDON WOULD COST YOU £1,830 Lonres/Dataloft The housing crisis is moving up the political agenda. It’s not only hurting first-time buyers: it’s affecting all of us, from families squeezed into flats to millionaires despairing about taxes. What does it mean for you, asks Martina Lees truths HOUSING HOUSING CRISIS CRISIS CRISIS 2015 HOME HOUSING HOUSING CRISIS CRISIS

- 3. problems,” says Alan Ward, chairman of the Residential Landlords Association and owner of 10 rental properties around Manchester — two of which he built himself. “We are in a business to provide a good product to a growing demand.” What about landlords who break the law? “There are enough rules, but they are not enforced.” FIRST-TIME BUYERS For the past year Lucia and Conor Hull, with their daughters, Juliet, 1, and Ella, 3, have been living with Lucia’s parents in Ealing, west London. With joint earnings of £60,000 a year, they can’t even afford to rent in the area (useful for childcare), let alone buy. “Renting would cost half of our income,” says Lucia, 33. And buying? Hamptons’ generation- gap data show the couple would be able to get a mortgage for a 445 sq ft one- bedroom flat locally — provided they could save more than a year’s income for a 20% deposit of about £62,000. In 1975, they would have been able to afford a three-bedroom terraced house (974 sq ft) with a £37,000 deposit in today’s money. “I think it’s appalling,” says Lucia, who works as an events organiser while Conor is training to be a physics teacher. “For my husband, it’s difficult to live with his in-laws. It puts a lot of pressure on our marriage.” Lucia’s father, Richard Platings, 66, who runs an events lighting business with his wife, Isobel, 59, says they would have liked to help their daughters buy. “Unfortunately we don’t have the means.” Over the past decade, the proportion of Making ends meet From left, Nathan Jackson, Grace Hall, Hannah Wright, Antoine Thevenet, Heather Elliott, Jamie Hall and Stephanie Ronson. They share a six-bedroom house in Hackney, where prices have risen 441% in a generation years ago with huge debts, she lost their three-bedroom house in a shared- ownership scheme in Hertford and gave up her full-time job as a manager in the probation service so she could pick up Anna from school. Scully found a part-time role at a French holiday lettings firm, “but now I can’t even get a rented home for myself”. The only landlord who would accept them on partial housing benefit let them a damp two-bedroom house without central heating in nearby Ware. It was so icy that, after Scully complained, the council’s environmental health service ordered him to do £20,000 worth of repairs for “a significant hazard of excess cold”. The landlord has since served Scully notice that she will be evicted in June. “My daughter keeps asking me where we’re going to live and I can’t tell her.” They now face homelessness, as all the local lettings agents refuse tenants on benefits, even if they work. “The irony is, my story can happen to anyone,” Scully says. She’s right: middle-income earners such as her made up two-thirds of all new housing benefit claimants in the past six years, reports the National Housing Federation. About 213,000 private tenants were evicted last year after asking for basic repairs, the House of Commons Library reported in November. (A new law passed last month means courts can no longer enforce such evictions.) And the end of a private tenancy is now the most common cause of homelessness, says a recent study by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation. “I’m not denying that there are shoes,” Frey says. “We don’t interact because there’s no place to do it. It becomes a place to sleep, not to live.” The compromise means her room costs a below-average £450 a month, “which is why I stay”. One in six shared homes across Britain has no living room — up from one in 10 three years ago, SpareRoom.co.uk found in its annual survey of more than 10,000 flatsharers. It’s a symptom of the rise of the private rented sector, which has more than doubled since the early 2000s from 2m to 4.4m households in England. It’s good news for anyone wanting to go into buy-to-let, but it is harder for a private tenant to save up for a deposit while spending an average of 40% of their income on rent — compared with the 20% that a homeowner pays on their mortgage. Those high costs cause more than half of 24- to 29-year-olds to delay having children for as much as five years, a recent YouGov poll for Shelter found. A 10th of those surveyed admitted they wanted to leave their partner, but hadn’t because they couldn’t afford a new place to live. Yet the worst affected, according to Danny Dorling, professor of geography at Oxford University and author of All That Is Solid, are children in their early teens who have had to move schools and lose friends several times “because mum or dad cannot pay the rent the landlord wants”. A million families with children joined the private rented sector in the past decade. One of them is Sonia Scully, 41, and her daughter, Anna, 10. When Scully’s husband left her two in Hull’s HU4, you can now get almost double the space for your money compared with 1975. “The shift of the economy southwards and the decline of industrial employment has had a particular impact,” Morris says. This also shows how the crisis is not merely about building too few homes. Too often, we’ve built the wrong type of homes in the wrong places. In the six years since the financial crisis, more than twice as many homes have been completed in struggling Hull (2,880) than in soaring Brighton (1,360), Home’s analysis of government figures shows. In total, England needs about 240,000 new homes a year just to meet the population growth — let alone make a dent in that 2m backlog. Yet, last year, it completed less than half that at 112,400. As the wealth gap grows, we are also using homes less efficiently. “Space is income elastic,” says Kate Barker. “The richer you are, the more space you want.” (Surely everyone needs a leather- lined cigar parlour in the basement?) Rebecca Tunstall, director of the Centre for Housing Policy at the University of York, used census data to calculate the growing mismatch between people and rooms. In 2011, the best-off 10th of the population had five times as many rooms per person in their houses as the worst- off 10th — up from 3.7 times in 2001, the fastest rise in a century. Behind all those numbers, however, are real people’s lives. Here is what they look like. RENTERS The primary-school teacher Nicola Frey, 33, has no living room in the house in Kingsbury, northwest London, that she shares with three other thirtysomethings. “Home should be a place that you come back to and enjoy; here it’s just four walls to keep your BRITAIN’S NET HOUSING WEALTH IS UP 58% SINCE 2003 TO £3.2 TRILLION, A THIRD OF WHICH IS HELD BY OVER-65S Chartered Institute of Housing Kate Mably and her partner, Ant Fanshaw, sold their complex of barn conversions near St Austell in Cornwall for about £1m, but have been living in a caravan for nine months as they cannot find a suitable home to downsize to. Ironically, Fanshawe’s pod-building business is thriving on the downsizer market (halodesign.co) HOUSING HOUSING CRISIS CRISIS 2015 HOME 14 HOUSING HOUSING CRISIS CRISIS

- 4. 19.04.2015 / 15 £70,000 in tax and fees, according to research by Dataloft for Landmark Lofts. The loft conversion firm reports a 64% jump in inquiries in the first two months of this year compared with the same period in 2014. DOWNSIZERS Lord Best has campaigned for tax incentives to help older people downsize, but on the eve of turning 70, he has yet to persuade his wife to leave the four-bedroom home near York where they raised four children. “In keeping with so many others of our generation, Lindy and I discuss downsizing endlessly, but somehow fail to agree on where and when we should move,” says the peer. “We love the house, but the children have all left home. While I am fighting fit in my ‘extended middle age’, we should definitely be planning a move to somewhere smaller and more manageable — without steps and stairs, within a stroll to shops. If we leave it until a health crisis, our choices will be more limited. However, the housing on offer is often simply not attractive enough.” The Bests are among 2.3m households of over-65s with two or more empty bedrooms, according to the 2011 census. Most only move once the death of a spouse, an accident or a maintenance disaster forces them to do so. “Culturally we just hang in there as long as we possibly can,” Best says. Michael Longcroft, 74, lost his wife, Diane, to cancer a few years ago. “I miss her terribly and I find living on my own bloody awful,” says the retired engineer, who is now selling the four-bedroom house in Hail Weston, Cambridgeshire, Wilkeses have borrowed 95% of their home’s value. As Jo puts it: “We’re mortgaged up to our eyeballs. How will we be able to help Molly one day?” Since the credit crunch, the plight of the second stepper has become more prevalent. Simply getting onto the property ladder is no longer a guarantee of being able to move up it. “While a lot of emphasis is placed on the difficulty faced by first-time buyers, the effect on second steppers are often underestimated,” says Lucian Cook, head of research at Savills. Those who bought their first property after the financial crisis “haven’t seen enough growth on their home to fund a step up the housing ladder”. Cook calculates that the average home bought by a first-timer five years ago has risen in value by about £23,000. Yet mortgage rules are stricter and bigger homes have gone up proportionally more, which means those families need an (often insurmountable) deposit of £61,500 to trade up. Some compromise by squeezing into smaller homes to keep children in their favoured school; others buy further out and commute longer. Many, such as Andre Ribeiro, a property manager, and his wife, Alfke, a financier, extend instead. The couple paid £60,000 for a loft conversion that added two bedrooms, a bathroom and a roof terrace to their two- bed flat in Balham, south London. “We moved up, instead of out,” says Andre, 42. Upsizing from three bedrooms to a four-bedroom house in the Ribeiros’ borough of Wandsworth costs an estimated £280,000, plus more than Conor and Lucia Hull have a joint income of £60,000 a year. They and their daughters, Ella and Juliet, live with Lucia’s parents in Ealing ”Renting would cost half of our income. For my husband, it’s difficult to live with his in-laws. It puts a lot of pressure on our marriage” 25- to 34-year-olds who own their homes has plummeted from 59% to 36%, the English Housing Survey reports. Where do they all go? They rent. Or, like Lucia, one in four adults under 35 live in their childhood bedroom, according to the Office for National Statistics. Of those that do buy, the Council of Mortgage Lenders estimates that almost two thirds get a leg up from their parents — and that amounts to about £2bn a year. A gulf is opening up between those who can borrow from the bank of mum and dad and those who can’t, says Kate Barker. “It’s made more uneven, I bet, not only by whether your parents have housing wealth, but whether they develop Alzheimer’s. I know that’s a really tasteless remark, but it’s true — they’d have to pay for the care.” That makes Elizabeth Wood, 39, an exception: in January, the personal assistant bought her first home, a two- bedroom new-build flat in Warmley, near Bristol, without any help, for £118,000. “It took me 15 years to save money for a deposit, and in order to do that, I’ve spent the past two decades of my life renting in shared houses.” No wonder it took so long: the average deposit for a first-time buyer is now £26,000 — more than eight months of their gross annual earnings. That is double the four months’ salary required on average in the five years before the financial crisis, exclusive research by Savills estate agency shows. In London, it’s far worse. First-time buyers earn £56,300 a year on average — and have to stump up more than 14 months’ income (£67,000) for a deposit on the average first-time buyer house price of £238,600. That is forcing the age of the average first-time buyer in the capital to 37, analysis by JLL shows. SECOND STEPPERS With a toddler and no garden, Jo and Iain Wilkes, both 40, were bursting out of their small two-bedroom in Shoreham, East Sussex — yet on their NHS salaries, upsizing seemed out of reach even in neighbouring , and less fashionable, Worthing. “We couldn’t afford Brighton, so we had moved to Shoreham. But house prices there went up something like 17% in two years,” says Jo, a physiotherapist. After a six-month search, they came across a three-bedroom house at Cissbury Chase, a new Barratt development in Worthing, where they could buy with a 5% deposit and a 20% Help to Buy equity loan. “Without it, we wouldn’t have been able to buy a bigger home,” Jo says. The Wilkeses moved into the £270,000 property in November. Molly, now 3, “loves her pink and purple bedroom”. And for the first time, she has a garden to play in. However, the Vicki Couchman; Francesco Guidicini; John Lawrence

- 5. 16 “summarised people’s hopes to better themselves”, says Deborah Mattinson, founder of the research and strategy consultancy Britain Thinks. Today, however, policies aimed at easing the housing crisis fail to capture the public imagination. “It’s about fear and not about hope,” she adds. In 2001, when homeownership in England and Wales peaked at 69%, all the councils combined built only 160 new homes. Private housebuilders never filled the gap, and not-for-profit housing associations have built only about 19,000 homes a year on average since 1978, government figures show. House prices rocketed, homeownership fell to 64% and buy-to-let landlords took on the social tenants who could no longer find council homes. Over the past 20 years, the housing benefit bill doubled to about £25bn a year. The financial crisis amplified it all, more than halving the number of home purchases to 730,000 in 2009 and doubling demand for private renting. It also cut the number of smaller housebuilders by half to 2,400. “Put simply, if buyers can’t buy, builders can’t build,” says Stewart Baseley, executive chairman of the Home Builders Federation. The result is a market where, for those lucky enough to own, more and more of their wealth is tied up in property. over-60s would be interested in buying a retirement property. If all of them were able to do so, it would free up 3.29m properties for the next generation, including almost 2m three-bedroom homes. HOW DID WE GET HERE? In 1918, more than three-quarters of families in England and Wales were renting privately while the rest owned property. Then came the “homes fit for heroes” campaign and, after the Second World War, a three-decade building boom during which councils delivered about 90,000 homes a year. By 1980, when almost a third of the population were social tenants, Margaret Thatcher introduced policies for a “property- owning democracy”, including the right for council tenants to buy their homes at a discount. Since then, 2.5m homes with a total value of more than £100bn have been sold under Right to Buy, reports Professor Steve Wilcox of the Centre for Housing Policy at the University of York. Half of that has gone into the buyer discounts, and £55bn to the Treasury. “Only an insignificant amount has gone back into housing,” Best says. Despite that, Right to Buy was one of the most popular policies ever because it where they lived for more than 30 years for £550,000. “As lovely a home as it is, it’s too lonely. Recently I had a mild stroke, which made it difficult to walk.” After looking through the specialist Retirement Homesearch, he has his eye on a riverside three-bedroom flat in a nearby village, down the road from one of his two sons. “I’m a boating man and there I could moor up outside the door.” With the baby boomers hitting retirement, demand is rising for aspirational property to “rightsize” to, rather than downsize with a sense of dread. Yet supply is far from keeping up: retirement housing make up less than 3% of new homes in the pipeline, according to a report by Knight Frank estate agency. Research by the independent think tank Demos found that a quarter of HOUSING HOUSING CRISIS CRISIS CRISIS 2015 HOME HOUSING HOUSING CRISIS CRISIS “THE LAND ASSEMBLED FOR HS2 IS ENOUGH TO BUILD 220,000 HOMES ON — ALMOST AS MUCH AS ENGLAND NEEDS IN A YEAR” NHF Philippa Roberts wants to downsize from her eight-bedroom house in Ascot after her six children have flown the nest, but hasn’t found a buyer in a year (£3.5m; bartonwyatt.co.uk) Peter Tarry; Matt Reading

- 6. 19.04.2015 / 17 Home has become an investment, like gold or art, not just a place to live. HOW DO WE SOLVE IT? Political decisions got us into this mess; political vision is the only way out. Last month, for the first time, the whole housing sector — those who build, rent, plan, design and campaign for homes — came together at the Homes for Britain rally in Westminster, demanding that the new government draw up a long-term plan to solve the housing crisis within a generation. “Honk for homes,” one placard read; and another, held by a blonde in her twenties: “We don’t want to stay home 4ever.” “There has been a complete failure by successive governments to tackle the housing crisis,” says David Orr, chief executive of the National Housing Federation, the umbrella body for housing associations, which organised the rally. Over the past five years, the coalition has made more than 500 announcements that included references to housing and had four housing ministers. We don’t need any more short-term vote-winners, Orr adds. “What we need is politicians with vision, who will make housing a priority and look to long-term solutions that go beyond their five-year term.” “I’m 100% behind that,” Best says. Kevin McCloud, the Grand Designs presenter, and Sir Michael Lyons, the former BBC Trust chairman who authored the most significant property review of recent years, have also backed the campaign . So have 34 cross- industry organisations including the Royal Institute of British Architects, the Residential Landlords Association, the Home Builders Federation and Shelter. Barker agrees that no government has grasped the nettle of housing since she published her report. Measures such as Help to Buy or Right to Buy make a particular group happy, while others — such as those renting privately — suffer. n How is the housing crisis affecting you? Tell us on Twitter at @TheSTHome using the hashtag #housingcrisis Ataxonallyourhouses A decade or two ago, you bought a normal house in a normal area, and now — thanks to the property price boom and a dose of luck — you are one of Britain’s 400,000 “homillionaires”. Which makes you rich in equity, (probably) poor in cash and a political target. Soaring house prices, the result of decades of building far too few homes, have also made it entirely rational to invest in property. In turn, our drive for bigger properties, second homes and buy-to-lets has made prices even less affordable for the next generation. We need to break that cycle, argues the economist Dame Kate Barker. “The idea that you can do it just through supply seems to me optimistic,” she says. How do you even out demand in a property- obsessed nation? With tax, says Barker, who proposes a capital gains tax on main homes rolled up through our lifetimes. “But, you know, this is political suicide.” Labour’s proposed mansion tax on £2m-plus homes, confirmed in its manifesto, is another stab at this idea. A more widely supported alternative is to reform council tax, as Wales did in 2005. Countrywide, Britain’s biggest residential estate agency, suggests a new band I at the top that pays 3.3 times what band A pays, up from three times. A £5m band H home in Camden, which now pays £2,640, would pay £4,620 as band I. A mansion tax would cost £10,640. At the same time, the 1991 house values on which council tax is based should be brought up to date. “At the moment, a £350,000 home and a £35m home pays the same – that’s just weird,” says Lord Best, chairman of the all-party parliamentary group on housing. This idea was backed by 68% of respondents to a YouGov survey for the HomeOwners Alliance last month, compared with 60% who supported a mansion tax. Any tax is unpopular, Barker admits. “People don’t want houses built and they don’t want houses taxed. But if they say that, they can’t turn round and say, ‘Hey, my child can’t afford a house.’” Martina Lees you? Tell us on The Wilkeses used Help to Buy TIMES+ Members can save 25% at Charles Tyrwhitt. To find out more, visit mytimesplus.co.uk

- 7. Franck Reporter/Getty A new dawngeneration” of them (no word on where). Garden cities with green spaces and spacious homes herald a return to big developments on new sites, but Milton Keynes, the last of the postwar new towns, delivered only 3,500 homes a year at its peak. And they take decades to build: Northstowe, a new town of up to 10,000 homes on the edge of Cambridge, was discussed 10 years ago, but construction has only just started. The fixes Remember Labour’s failed eco-towns? The nimbys will likely be the biggest stumbling block. Given the scale of the crisis, say KPMG and the charity Shelter, starting at least five garden cities should be a legacy of a new government. 3GO UP The facts Height restrictions make it impossible to build above seven storeys in about three-quarters of central London, which is why it has fewer skyscrapers per person than most cities in the developed world, according to the LSE. Still, there are 120 towers under construction or with consent in the capital, providing homes for 120,000 people — equivalent to the population of Cambridge The fixes “London’s population grew by 1.1m over the past 10 years and is forecast to grow by 1m over the next decade,” says Nick Whitten, associate director of residential research at JLL. “Upwards is the only realistic option.” Can we build more homes? Yes, we can. Industry experts offer 10 ways to fix the shortage HOUSING HOUSING CRISIS CRISIS 2015 HOME 20 HOUSING HOUSING CRISIS CRISIS It’s easy to point to £350m-worth of empty mansions rotting away in Belgravia or the Bishops Avenue, north London, and blame the faceless foreign speculators who own them for Britain’s housing crisis. It’s much harder to solve the real problem: each year we build 100,000 fewer homes than we need. So how do we get to 240,000 new homes a year? Home asked more than 30 of the housing industry’s top movers and shakers for their solutions. Here are their answers (banning overseas investors is not one of them). 1GO OUT The facts Seven in 10 new homes are built on brownfield land, yet the government estimates that there is only enough of it for 200,000 new homes by 2020 — less than 14% of what we need. Where else can we go? Out into the green belt. That does not mean concreting over the countryside, says Paul Cheshire, professor of economic geography at the London School of Economics (LSE). He found that only a quarter of green belt inside London’s boundary consists of parks or protected or public-access land. The remainder is mainly intensive farmland (with less biodiversity than suburban gardens) — and golf courses, which cover more of Surrey than houses do. The fixes Review what we call green belt, says Countrywide, Britain’s biggest estate agency. It points out that the concept dates from more than 70 years ago, when cities were in decline. The Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (Rics) wants a new “amberfield” category for “brownfield land and low-quality green belt and greenfield land that’s ready to go”. But how to get past the nimbys? Pay them. Dame Kate Barker, the economist who first identified the housing shortage in 2004, suggests direct payments and council tax cuts for those affected. 2BUILD NEW TOWNS The facts The Conservatives back “locally led” garden cities of about 15,000 people, including at Ebbsfleet, Kent, and Bicester, Oxfordshire; the Liberal Democrats want at least 10 and Labour says it will build a “new

- 8. 19.04.2015 / 21 SUNDAY TIMES DIGITAL Discover how Britain’s housing market has evolved over the past 35 years in our interactive guide, on tablet and at thesundaytimes.co.uk/home 7ENCOURAGE DOWNSIZERS The facts Some 3.4m households consisting of over-65s are potential “right-sizers”: 1.1m have one spare bedroom and 2.3m have two or more spare bedrooms, according to census data. Yet Britain has only about 530,000 retirement properties, of which only a fifth can be bought, the think tank Demos has found. The fixes Lord Best wants developers to meet this need and a “help to move” government scheme offering over-65s stamp-duty breaks on properties under £250,000, and loans to bridge any gap between their previous and new home. 8FINE-TUNE PLANNING The facts “We have a crisis in planning,” says Kevin McCloud, the Grand Designs presenter and chairman of HAB Housing. “It has stopped being a creative process and become a reactionary one, with skeleton staff who moderate mediocrity.” Mark Clare agrees that “the level of planning just takes too long”. The Home Builders Federation (HBF) estimates that 150,000 plots are stuck in the planning system awaiting final approval. The fixes Housebuilders don’t want any large-scale planning reforms. The National Planning Policy Framework, which cut some 1,300 pages of planning rules to 65 three years ago, should have time to bed in. However, it should be homes over five years, the Chartered Institute of Housing estimates. “The simplest first step,” says Naomi Heaton, chief executive of the property fund London Central Portfolio, “is to bring derelict and often local-authority-owned empty homes back into circulation.” 6IMPROVE RENTING The facts Britain’s 9m private tenants, who include 1.5m families, rent from about 1.4m landlords, estimates the National Landlords Association (NLA). The coalition’s £1bn Build to Rent scheme, aimed at getting institutional investors such as pension funds to back new managed blocks, has seen only £150m worth of contracts signed since 2012. The fixes Matt Hutchinson, director of the flatshare site SpareRoom.co.uk, says raising the tax-free allowance on letting out a room in your home would increase supply and help keep rents down. “The current £4,250 threshold hasn’t changed since 1997,” he says. Longer tenancies would make renting more family friendly, says Shelter, which wants five-year terms as the default. And, despite the fact that there are already more than 100 laws and regulations governing the private rented sector, in 2012, 150,000 more people were prosecuted for not having a TV licence than for poor or criminal property practices. 4RELEASE PUBLIC LAND The facts The public sector owns about 40% of larger sites suitable for housing development. The fixes If Mark Clare, chief executive of Barratt, Britain’s biggest housebuilder, became prime minister, he says he would “prioritise the identification and release of surplus public-sector land that would both raise funds and increase the supply of land for housing”. Savills estimates that we could build as many as 2m new homes on government land. 5BUILD MORE SOCIAL HOUSING The facts Housebuilding by councils has dropped 99% since 1980; last year, housing associations built 23,920 homes. Between 2011 and 2015, the government spent £4.5bn on affordable homes, while housing associations put in £15bn of privately raised money. About 40% of the annual £25bn housing-benefit bill goes to private landlords. The fixes Raise government funding for housing associations to double their output, says Lord Best, chairman of the all-party parliamentary group on housing. “It’s like Crossrail or HS2 — it’s investment that pays back in the long term.” Councils, too, should be brought back into play by allowing them to borrow more against the future rent from their social homes, he adds. This would allow councils to build 75,000 new enforced, says Stewart Baseley, chairman of the HBF. A fifth of councils still don’t have — as required — a local plan in place for a five-year supply of housing land, and the lack of such policies is the biggest cause of planning appeals. 9FAST-TRACK DELIVERY The facts Housing markets don’t respect local authority boundaries. Lack of co-operation across council boundaries is a big barrier to the delivery of new homes, according to Rics. The fixes Set up Olympics-style delivery units with compulsory purchase orders to assemble land named in local plans. 10DIVERSIFY HOUSEBUILDING The facts Since 1988, severe land restrictions and red tape have reduced the number of developers building 100 homes a year or less by 80%, to about 2,400 last year, the HBF estimates. Since the credit crunch, construction costs have spiralled — hitting builders of all sizes. Andy Hill, a regional housebuilder, says he now has to pay nearly twice as much for scaffolding as he did last year. The fixes The planning solutions, outlined above, would help the small guys, as would investment in training, says the NHBC. The architect Lord Rogers says he would also set up factories for housing, “allowing for much faster and more cost-effective construction.” What do you think should be done? Tell us @TheSTHome #housingcrisis

- 9. 19.04.2015 / 23 1946 1950 1955 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2013 1960 £350,000 £300,000 £250,000 £200,000 £150,000 £100,000 £50,000 £0 350,000 300,000 250,000 200,000 150,000 100,000 50,000 0 Nominal house price Labour Labour LabourConservativeLabour Conservative CoalitionCon Nominal house price Local authorities Private market Housing associations Sources: Department for Communities and Local Government, Nationwide, HM Treasury, Shelter/KPMG HousingsupplyinEnglandsince1946 Councils have stopped building homes, but the market and housing associations have failed to plug the gap — so prices have soared New dwellings per year along a reopened Oxford-to-Cambridge railway line. n Review laws on compulsory purchase to help assemble land at low cost and to allow the uplift in value when it is developed to be captured for infrastructure. n The Lib Dems’ big idea is “rent to own” — a kind of hire-purchase system that lies between renting and owning. Occupants of housing-association homes would pay rent, but after 30 years of rental payments the property would become theirs. It is not clear what happens if they want to move earlier. n New energy-efficiency targets for both homes and buy-to-lets. Homeowners who improved their property by at least two bands would have their council tax reduced by £100 for 10 years. There would be a “feed-out tariff” to reward homeowners who insulate walls. n “Encourage multi-year tenancies”, and offer help-to-rent loans to tenants to cover their deposits. n Order landlords who fail to improve defective properties to refund rent. n Make new developments subject to planning conditions that they be occupied — or double their council tax. UKIP n Ukip hasn’t set a target for housebuilding other than to say that it wants 1m new homes to be built on brownfield sites by 2025. It would create a register of available brownfield sites and grants of up to £10,000 per plot to help with decontamination. Houses built on brownfield sites and sold for no more than £250,000 would be exempt from stamp duty on the first sale. n Local authorities would no longer be forced into housebuilding targets set by central government. n Residents could overturn planning permission granted to large developments — if they could collect the signatures of 5% of the local electorate, there would be a binding referendum. n The Help to Buy scheme would only apply to British nationals. n Legislation would allow lenders to offer heritable mortgages, making it easier, the party claims, for older people to buy property with a mortgage. The four leading parties agree on the need for a housing shake-up, but the devil is in the detail. We assess their strategies for home help C H A N G E S W E W A N T T O S E E n Commitment to a target of how many new homes will be built and where. Ensure a mix of property types to suit local and long-term needs. Properties should be well designed, with high-quality construction methods. n Stop the right to buy. Enable councils to build more by raising their borrowing cap and relax rules for housing associations, so councils can double their output. n Add new council-tax bands at the top end and revalue all homes for council-tax purposes. Stop discounts for single households and empty homes. n Raise the £4,250 tax-free allowance for letting out spare bedrooms to increase supply (and help people stay in their homes if they need extra support). Introduce standard six-month, one-year and three-year tenancy contracts. Encourage build-to-rent. n Help older people who want to downsize with stamp-duty breaks on purchases under £250,000 by over-65s, and offer equity loans to bridge price gaps between their previous and new homes. This would also encourage private housebuilders to build more for this age group. n Swap low-value green belt for protecting better-quality land elsewhere. Introduce a new “amberfield” category for brownfield and low-value green-belt land identified by councils as ready to go. n Resource planning departments properly, and force all councils to adopt a local plan within six months. n Treat large housing projects as infrastructure, with Olympics-inspired delivery bodies. Include big-picture thinkers, regional representatives and detailed infrastructure groups. n Build both new towns and urban extensions. Reduce council tax of residents who are directly affected by development. n Boost the status of the housing minister and appoint a capable, charismatic lobbyist. CONSERVATIVES n Extend the right to buy to 2.5m housing-association tenants. n Local authorities would have to sell the most valuable council homes when they become vacant and replace them with cheaper properties. The money raised would also be paid into a fund to help develop brownfield land. n First-time buyers could register for a new home at what is claimed to be a 20% discount. Under the Starter Home scheme, developers on brownfield sites would be excused from paying towards infrastructure, and from the requirement to add affordable housing, in return for offering homes for less than £250,000 — or less than £450,000 in London. n A new London Land Commission will identify and release public-owned land. n Local authorities will be obliged to allocate land for individual building plots, to give self-builders a chance. n The equity loan part of the Help to Buy scheme will be extended to 2020. A Help to Buy ISA will be available to top up deposits by up to £3,000. n Properties worth up to £1m will be free of inheritance tax. LABOUR n Build 200,000 new homes a year by 2020, possibly by forcing providers of Help to Buy ISAs — a coalition policy it would enact — to invest money from savers in a future-homes fund. It claims this would provide £5bn to build an extra 125,000 homes over five years. n “Use it or lose it” powers to make builders develop land that has been granted planning or force them to sell it. n “Right to grow”, whereby towns that have overstepped their boundaries would be able to force neighbouring authorities to release land for development. HOUSING HOUSING CRISIS CRISIS CONSERVATIVES CRISIS 2015 HOME HOUSING HOUSING CRISIS CRISIS Who holds Dan Kitwood/Getty n Reform tenancy law. Three-year tenancies would become the norm, though with break clauses allowing tenants to leave the property early. n Ban “unfair” letting fees and restrict the rate of rent rises. nRaise council tax on empty properties. the key? LIBERAL DEMOCRATS n The Lib Dems have out-promised Labour by saying they will help 300,000 homes a year to be constructed. This will be achieved partly by building 10 new garden cities, five of which will be SUNDAY TIMES DIGITAL Hear from all the parties in a video interview, on tablet and thesundaytimes.co.uk/ homevideo