Module 01 Discussion- Oxygenation and Physiological Needs Rubric

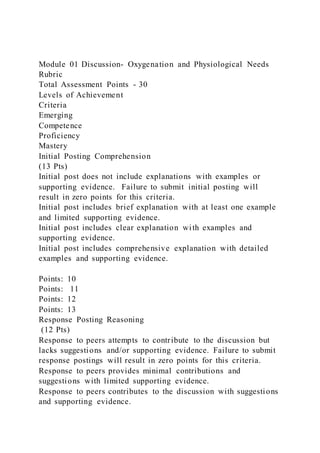

- 1. Module 01 Discussion- Oxygenation and Physiological Needs Rubric Total Assessment Points - 30 Levels of Achievement Criteria Emerging Competence Proficiency Mastery Initial Posting Comprehension (13 Pts) Initial post does not include explanations with examples or supporting evidence. Failure to submit initial posting will result in zero points for this criteria. Initial post includes brief explanation with at least one example and limited supporting evidence. Initial post includes clear explanation with examples and supporting evidence. Initial post includes comprehensive explanation with detailed examples and supporting evidence. Points: 10 Points: 11 Points: 12 Points: 13 Response Posting Reasoning (12 Pts) Response to peers attempts to contribute to the discussion but lacks suggestions and/or supporting evidence. Failure to submit response postings will result in zero points for this criteria. Response to peers provides minimal contributions and suggestions with limited supporting evidence. Response to peers contributes to the discussion with suggestions and supporting evidence.

- 2. Response to peers offers substantial contributions and detailed suggestions with supporting evidence. Points: 9 Points: 10 Points: 11 Points: 12 Spelling and Grammar (3 Pts) Six or more spelling or grammar errors. Detracts from the readability of the submission. No more than five spelling or grammar errors, minimally detracts from the readability of the submission. No more than three spelling or grammar errors. Does not detract from the readability of the submission. No spelling or grammar errors. Points: 1 Points: 2 Points: 2.5 Points: 3 APA Citation (2 Pts) Six or more APA errors reflected throughout initial and response postings. No more than five APA errors reflected throughout initial and response postings. No more than three APA errors reflected throughout initial and response postings. APA in-text citations and references are used correctly with no errors in initial and response postings. Points: 0 Points: 0.5

- 3. Points: 1 Points: 2 Roles of Shared Leadership, Autonomy, and Knowledge Sharing in Construction Project Success Hassan Imam, Ph.D.1 Abstract: Drawing upon self-determination theory, this study discusses in depth the role of team members’ autonomy and knowledge sharing in construction projects. The main purpose of the study is to investigate the rarely discussed role of shared leadership in the successful completion of these types of projects. The data were collected from 216 site engineers working in Tier 3 construction companies on two time points. PROCESS Macro was used to test the hypothesized framework. The results showed that shared leadership plays a direct, significant role in the successful delivery of projects and, through members’ autonomy, meets individual psychological needs. Slope analysis revealed that knowledge sharing moderates the relationship between shared leadership and autonomy. The present study’s framework deepens the understanding of construction projects with self- determination theory that shared leadership fulfills workers’ psychological needs (competence, relatedness, and autonomy) and leads project deliverables. With a multifaceted project approach, this study highlighted that

- 4. shared leadership is not limited to one dimension of project success but positively impacts project cost, client use, effectiveness, satisfaction, performance, and time management. DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0002084. © 2021 American Society of Civil Engineers. Author keywords: Shared leadership; Knowledge sharing; Project success; Self-determination theory; Autonomy. Introduction The construction industry is one of the most costly, technically de- manding, and risky industries and commonly involves long time frames (Ahmad et al. 2020). The general purpose of a project is to meet all stakeholders’ needs (including project workers), but professionals, building contractors, and even researchers tend to place much of their emphasis on technical aspects and how triple constraints (time, cost, and scope) can be efficient in meeting project deliverables (Fulford and Standing 2014). A large number of construction management and engineering studies discuss these technical aspects, but rarely do researchers ever discuss the human role in projects as a critical success factor (Phua 2012). Likewise, individual-level constructs (i.e., workers’ psychological needs) are seldom taken into consideration in connection with construction project performance (Phua 2013). It is equally important to discuss project leadership and the development of construction workers’ skills because both of these are significant, practical factors —

- 5. for two major reasons. First, inappropriate leadership style increases uncertainty of authority, power, and directions, thereby posing a threat to project success (Müller and Turner 2007). Second, sustain- able human development (i.e., expansion of human capabilities and well-being) falls under the scope of project leadership, and thus far, this aspect has attracted very little attention from project researchers (Byrne and Barling 2015; Muñiz Castillo and Gasper 2012). Leadership style can be seen as one of the major reasons for a project’s failure because in traditional projects (particularly in conventional construction projects), an appointed leader at the top gives directions and then assesses the progress being made through- out the project (Nixon et al. 2012; Turner and Müller 2005). These types of leaders do not strengthen worker autonomy, and they do not share project information well (Ellerman 2004, 2009). The concept of shared leadership, in which the role of leadership is shared among team members and where cooperation could be a common practice, has emerged in the management literature as an effective leadership behavior in organizations (particularly those in which task complexity and team interdependence are high) (Huang 2013; Kozlowski et al. 1996; Pearce and Sims 2002). Put

- 6. simply, a shared approach from leadership to achieve the goals amplifies the employees’ performance (Gupta et al. 2010). Observing the posi- tive results of shared leadership in different domains (e.g., health- care, education, and management) (Carson et al. 2007; Judge and Ryman 2001; Printy and Marks 2006) led project researchers to think about how shared leadership could improve team functioning and project performance (Clarke 2012; Imam and Zaheer 2021). Owing to the fact that a project requires cooperation and collabo- ration between team members—and based on shared leadership properties (e.g., self-organized problem solving)—this is likely to result in positive project outcomes. Therefore, in light of the recent call for research, this paper seeks to answer how a shared style of leadership contributes to project success (PS) and human development (Imam and Zaheer 2021; Scott-Young et al. 2019). The context of this study is a construction project, where it is assumed that bureaucratic rules exist and that labor typically has less autonomy to initiate or improve project tasks (Holt et al. 2000; Silver 1990; Walker 2011). Thus, the present study takes a sustain- able human development approach to understanding the extent to which shared leadership fosters autonomy in project teams (Dainty et al. 2002). Normally, construction projects will have to deal with

- 7. changes (i.e., material, design, cost, or scope) from clients that require an adequate degree of communication between client and project manager to discuss the changes (Sun and Meng 2009; Yang and Wei 2010). A traditional project approach has one person influencing the project downward (vertical leader), who then com- municates the change requirement(s) to the concerned project team members, rather than to all members. This is because vertical lead- ership is heavily focused on the scientific management approach (i.e., task specialization and less involvement in decision- making) 1Riphah School of Business and Management, Riphah International Univ., Lahore Campus, Lahore 54000, Pakistan. ORCID: https://orcid .org/0000-0002-0740-0897. Email: [email protected] Note. This manuscript was submitted on June 26, 2020; approved on January 26, 2021; published online on May 11, 2021. Discussion period open until October 11, 2021; separate discussions must be submitted for individual papers. This paper is part of the Journal of Construction En- gineering and Management, © ASCE, ISSN 0733-9364. © ASCE 04021067-1 J. Constr. Eng. Manage. J. Constr. Eng. Manage., 2021, 147(7): 04021067 D

- 11. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943-7862.0002084 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0740-0897 https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0740-0897 mailto:[email protected] http://crossmark.crossref.org/dialog/?doi=10.1061%2F%28ASC E%29CO.1943-7862.0002084&domain=pdf&date_stamp=2021- 05-11 (Ensley et al. 2006). Because of high task interdependence in con- struction, limited circulation of information about change increases uncertainty and may affect the overall project (Fong and Lung 2007). There is also an increased chance that, when all the power and control are held by a single or dominant leader, then members may be involved in political games (Clarke 2012; Pinto 2000). Thus, an autonomous and knowledge sharing (KS) environment is vital for the construction team to use less time, remain within budget, and stay on schedule (Kuenzel et al. 2016). Therefor e, this study contemplates that sharing the role of leadership in the project not only increases KS among members but also makes members more autonomous and able to cope with project challenges (Worley and Lawler 2006) and adds to their knowledge, skills, and abilities (Swart and Kinnie 2003). This paper contributes to the project literature by taking the micro (individual) level and meso (project) level perspectives, in two ways: first, the human role in projects (particularly the

- 12. project leadership) is in its establishment phase and requires researchers’ attention (Byrne and Barling 2015); and second, to highlight that appropriate leadership not only fulfills clients’ requirements but at the same time also increases the capacity of people who are en- gaged in these projects by providing autonomy, transferring knowl- edge and skills so that they can help themselves (Ellerman 2009). Essentially, in response to the recent call for research (Scott- Young et al. 2019), this study focuses on project workers as agents of change, where shared leadership increases their ability to act and achieve project goals, rather than only communicating orders to get things done with minimum (or no) support (Imam and Zaheer 2021). Self-Determination Theory Self-determination theory, a metatheory, addresses why (and what) motivates humans to pursue a particular task/goal (Deci and Ryan 2000) and mainly focuses on “people’s inherent growth tendencies and innate psychological needs” (Ryan and Deci 2000, p. 68). The core of self-determination theory is made up of two distinct motiva- tional behaviors. The first behavior is autonomous motivational behavior—out of free will. Individuals’ goal/task achieving

- 13. behav- ior is not entirely dependent upon functional purposes (e.g., wage/ salary); they also act based on interest and fun (Fernet et al. 2010) or personal value fulfillment related to psychological needs (Millette and Gagné 2008) and expend extra effort in this connec- tion (De Cooman et al. 2013). The second behavior involves a feel- ing of external pressure and having to engage in an activity or to avoid punishment or feelings of guilt. This is called controlled motivation. Such behaviors, in which individuals feel obliged or a sense of external pressure, may negatively affect their well- being (Gagné 2003). Three main aspects—autonomy, relatedness, and competence— have been identified that promote motivation and are directly linked with innate psychological needs (Ryan and Deci 2017). Autonomy relates to people’s need to feel that they are in control of their behavior because they want to feel that they are the masters of their own destiny. Likewise, given the limited freedom with responsibil- ities and accountability to construction workers, autonomy may provide better project results. Competence is heavily related to achievement and the advancement of knowledge and skills, and so people need to build up their competence and develop a mastery over tasks. They are more likely to act because those tasks help them to achieve their personal/professional goals. Relatedness is

- 14. concerned with individuals’ need for belongingness and attachment to others, interdependence to some degree. The fulfillment of these three psychological needs help to attain the necessary self-determination level to achieve positive (personal and profes- sional) outcomes. Of the three aspects, autonomy is one of the most powerful influences on motivation, along with competence (Deci and Ryan 2000, p. 235). In light of self-determination theory, this study examines the question of how shared leadership fulfills workers’ psychological needs by leveraging autonomy at work and creates an environment of KS that expands worker knowledge and skills (Deci and Ryan 2000). Likewise, within the context of a project team, leadership sharing works as a multidirectional social process and as a collec- tive activity that allows for sense making and is embedded within a project (Fletcher and Kaufer 2003). Hypothesis Development Construction projects are complex and multifaceted undertakings that demand teamwork, cooperation, and collaboration among project members who share common goals and face common issues (Spatz 1999). Therefore, the increasing emphasis on teamwork (which involves a significant investment of intellectual capi tal

- 15. by a group of skilled professionals) has gradually led researchers to shift their focus from individual leadership to shared leadership (Houghton et al. 2003). Merely working on a team is not always associated with increased effectiveness (Ashley 1992), and teams often fail to live up to their potential owing to an inability to smoothly coordinate team members’ actions and a lack of effective leadership to guide this process (Burke et al. 2003). As a result, it is important to maintain practices of team leadership that are more predictive of successful outcomes, such as efficiency and produc- tivity. Shared leadership is explained as “a dynamic, interactive influence process among individuals in groups for which the ob- jective is to lead one another to the achievement of group or organi- zational goals or both” (Pearce and Conger 2003, p. 1). The difference between shared leadership and shared responsibility is abundantly evident in literature: the former distributes responsibil- ities and influence (Carson et al. 2007), while the latter emphasizes individual cooperative actions and attitudes, with team members then converting individual input into team output (Hollenbeck et al. 2012; LePine et al. 2008). Shared leadership creates a pattern of reciprocal influence in which the leader’s behavior influences members—and, in the same way, a member’s actions, such as coordination, increases mutual understanding with the leader (Carson et al. 2007). Applying

- 16. the shared leadership concept to a construction project promotes relationships among members that further facilitate the project’s key functions (i.e., cooperation, coordination, and problem sharing) (Crevani et al. 2007). Shared leadership divides power according to team members’ responsibilities and incorporates members into the process of decision-making (Robert and You 2018), and in con- struction projects, this division of the leader’s role may range from high to low (Robert 2013). Project success largely depends on leadership style (Müller and Turner 2007), and sharing a leader’s role among members creates a similar understanding of goals and objectives (Crevani et al. 2007). With an example from the plant construction and engineering industry, Hauschildt and Kirchmann (2001) found that performance (innovation success) increased by 30%–50% when multiple individuals took on a leadership role within project. This study argues that shared leadership is an intan- gible project resource where members develop trust and respect and are open to influences that improve team functioning, thereby meeting the success criteria (Carson et al. 2007). Therefore, the first hypothesis is as follows: H1: Shared leadership behavior increases the likelihood of project success. © ASCE 04021067-2 J. Constr. Eng. Manage.

- 17. J. Constr. Eng. Manage., 2021, 147(7): 04021067 D ow nl oa de d fr om a sc el ib ra ry .o rg b y A ra b A

- 20. er ve d. In construction projects, it is generally understood that tasks are repetitive and that authoritarian leadership is enough to complete all tasks (Giritli and Oraz 2004; Holt et al. 2000). However, this may not be correct in the current business climate, in which construction projects face industry-specific challenges (i.e., fluctuating con- struction activity), operating environment challenges (i.e., the need to integrate an increasingly large number of processes), and general business challenges (i.e., the growing size of projects and increased participation of foreign companies in domestic industries due to globalization) (Toor and Ofori 2008b). In this context, the role of leadership becomes more crucial for dealing with industry (as well as workforce) challenges (i.e., aging workforce) and dealing with change/transition, as well as teamwork and communicating project goals (Toor and Ofori 2008a). Therefore, project research- ers emphasize applying different styles of leadership in the con- struction industry to deal with overall challenges (Chan and Chan 2005; Toor and Ofori 2008b). It is pertinent to mention that project risk management is typically limited to technical aspects (i.e., fluc-

- 21. tuations in material costs and delayed cash flow); however, project managers face unknowns during the course of a project, in which human aspects (e.g., teamwork and goal communication) are also critical to project success and directly come under the purview of project leadership (Clarke 2012). For the smooth functioning of (non)routine tasks and dealing with uncertain situations, project team members require autonomy— the extent of individual freedom, discretion, and independence in carry- ing out tasks (Chiniara and Bentein 2016). Gemünden et al. (2005, pp. 366–367) identified four types of project autonomy: (1) goal de- fining, freedom to set personal goals, and their priority; (2) social autonomy, choices available for self-organizing within a project, including interaction with other members; (3) structural autonomy, maintaining one’s own identity and boundaries with others; and (4) resource autonomy, where one has the choice to use resources to complete an assigned task. All four types of autonomy are needed for construction project workers to be able to deal with client change requirements and maintain control over project tasks. Self- determination theory indicates that autonomy is an influential indi-

- 22. vidual’s psychological need that initiates self-motivated behavior toward need fulfillment. This study postulates, in light of self-determination theory, that shared leadership increases self-motivation by delegating influ- ence, authority in tasks, and responsibilities among members to ful- fill individuals’ psychological needs (Deci and Ryan 2000; Fausing et al. 2013). This autonomy provides confidence in members to devote their best efforts to a project and enables them to better deal with changing situations (Drescher et al. 2014; Fausing et al. 2013). Construction projects have more distinct and dispersed functions (logistically complex and very resource-intensive, with a major fo- cus on activity-based planning) than other projects (e.g., supply chain and risk management) (Al-Bahar and Crandall 1990; Turner and Cochrane 1993; Vrijhoef and Koskela 2005). Therefore, autonomy is crucial in obtaining better results, and shared leader- ship fosters required autonomy on a team (Fausing et al. 2013). In light of the preceding considerations, the second hypothesis is as follows: H2: Autonomy positively mediates the relationship between shared leadership and project success. Because of the diversity of tasks in construction projects, mem- bers with broader skill sets and educational backgrounds are re -

- 23. quired, and so autonomy becomes a prerequisite for performing assigned tasks. Likewise, to increase project efficiency, it is a leader’s responsibility to create a productive work environment where members can share their expertise and skills. Studies have demonstrated that shared leadership makes for efficient team functioning by creating a collaborative environment (Drescher et al. 2014) and increased social interaction among members (Conger and Pearce 2003). Working in an environment where employees have a higher degree of information sharing is better for mobilizing their creative potential (Wang and Noe 2010). They are able to solve tasks optimally and quickly by utilizing the available infor- mation than they would have otherwise—known as knowledge sharing (Christensen 2007), which is connected to an individual’s intelligence, convictions, and values (Hoegl and Schulze 2005). The exchange of information and ideas also becomes more impor- tant in construction projects because of their greater (financial and social) value and because of the technical tasks involved. Likewise, researchers have suggested that shared leadership is a better prac- tice for responding to the dynamic and changing characteristics of most projects (Clarke 2012). The human side of work brings skills and motivation to com- plete projects on time; however, employees expect that their psychological needs will be met. Owing to the temporally bound nature of projects, workers may not be motivated or committed

- 24. to a project, but they can still be motivated if they believe that they will acquire new knowledge and learn new things (Deci and Ryan 2000). Competence is related to achievement, knowledge, and skills that one feels are important to grow. For this, one needs to develop mastery over tasks in order to remain employable. To ex- pand project workers’ existing skills, an environment of knowledge sharing (where team members can share their project-related ideas and information) is important because one person alone may not possess all the skills required to complete a task (Pearce and Manz 2005). This study postulates that in a project where a leadership role is shared, members can share their knowledge and expertise with each other (Coun et al. 2019; Houghton et al. 2003). This KS environment increases workers’ skills, and they then feel more autonomous in carrying out their tasks (Pearce and Manz 2005). In construction projects, workers perform their jobs as a team, and a recent study demonstrated that team functioning improves by providing autonomy to workers (van Zijl et al. 2019). Drawing on self-determination theory, this study argues that shared leader- ship increases workers’ joint responsibility by providing autonomy and a trust environment that is conducive to cooperation and sharing knowledge with each other (Coun et al. 2019). However, in an environment where KS is frequent, workers will feel less dependent upon their so-called structural supervisor and others, and the level of perceived autonomy at work will be high. Thus, the third hypothesis is as follows:

- 25. H3: Knowledge sharing moderates the relationship of shared leadership and autonomy such that higher knowledge sharing on a project will increase autonomy, and vice versa. This study proposes a model in light of self-determination theory (Fig. 1) for construction projects by taking into account the human perspective and discusses the psychological needs Shared Leadership Project Success Members’ autonomy Knowledge sharing Proposed research model H1 H2 H3 Fig. 1. Proposed research model. © ASCE 04021067-3 J. Constr. Eng. Manage. J. Constr. Eng. Manage., 2021, 147(7): 04021067 D ow nl

- 29. and motivations of construction workers. The proposed model highlights that implementing shared leadership increases the like- lihood of success of construction projects, because such a leader- ship style addresses workers’ psychological needs by leveraging task autonomy and creating a KS culture. This distorts the general assumption that authoritarian leadership is sufficient to achieve project deliverables in construction projects, due to the repetitive nature of tasks (Holt et al. 2000), and highlights that shared leadership deals with contemporary challenges faced by the construction industry—particularly fluctuations in construction activity—and increases the participation of foreign construction companies in the domestic market (Toor and Ofori 2008b). Fig. 1 shows the proposed model and directions of the hypoth- esized relationships. Methods Data and Sampling The data were obtained from construction companies in two cities in Pakistan (Lahore and Islamabad). The author contacted 953 construction companies (Tier 3 construction companies involved in typically residential and small-scale commercial projects) contacted and asked to provide the contact information of site en- gineers, team size, and nature of their last completed project. Out of the 953 companies contacted, 565 responses were received, from which 459 companies were selected, because these companies were homogeneous in terms of their budgets [installed costs

- 30. were between $250,000 and $550,000, converted from Pakistani rupees (PKR) to USD based on the definition of medium-sized projects] and team size (10–25 members) in their last completed projects. Such projects are considered to be medium-sized projects (Byrne 1999) and are, with respect to team size, suitable for gauging the significance of shared leadership because “with increases in team size, the psychological distance between individuals can increase” (Pearce and Herbik 2004, p. 297). Site engineers were taken as a sample because they are respon- sible for managing parts of construction projects, overseeing building work, and liaising with quantity surveyors about the order- ing and pricing of materials, and they are also in close contact with project managers and workers. Thus, the site engineer’s response will be less biased and suitable as a source of information about leadership style of project managers, knowledge sharing on projects, workers’ perception of autonomy, and project success (Podsakoff et al. 2012). Paper-and-pencil surveys were distributed to site engineers from the selected companies. The questionnaire contained three filter questions to obtain information on the following factors: one must have completed a project on a team, the size of the team worked with, and the size of the budget on the last completed project. For respondents’ convenience, the questionnaire was

- 31. translated into the national (Urdu) language of Pakistan and then checked by two language experts. Few items were modified or back-translated (Brislin 1970). Before administering the survey, a pilot study was carried out to test the validity and reliability of the translated questionnaire, and the results were found to be reliable (De Vaus 2013, p. 114). The data were collected in two stages, with a 3-week interval to avoid common-method variance (Podsakoff et al. 2012), and in both stages, a separate page at the front of the questionnaire was attached that explained the purpose of the study and defined the variables. In the first stage, 371 responses out of 459 were re- ceived, in which questions on shared leadership and knowledge sharing were asked, along with demographic information. To match both stage responses, respondents were asked to identify their Pakistan Engineering Council registration number, which was then used as a unique identifier. After 3 weeks came the second stage, in which questions were posed about autonomy and project success, and 255 responses were received out of 371. After screening, 39 responses were discarded owing to incomplete or missing infor- mation. In the end, 216 usable responses were accepted for final analysis (overall response rate of 47.06%). The surveyed demographic characteristics were gender, educa- tion, and age. The sample was composed of 91.7% males and 8.3% females. Age was categorized in brackets, and the sample

- 32. contained 18- to 25-year-olds (29.6%), 26- to 33-year-olds (46.8%), and 34- to 41-year-olds (12.5%). In addition, 40.3% of the sample held a college-level degree, 39.4% a bachelor’s degree, 16.2% a master’s degree, 2.3% a technical degree, and only 1.9% had matriculated. Measures Independent Variable Shared leadership: This study operationalizes the concept of shared leadership (with sets of behaviors) in which the leader’s role is distributed among members of a team (at different points), rather than having a particular person directing a team (Lord et al. 2017; Wang et al. 2014). This was measured through a 26-item short scale adopted from Hoch et al. (2010). This five-facet scale is a combi- nation of transformational, directive, empowering, transactional, and aversive leadership behaviors [X2ð290Þ ¼ 607.38, comparative fit index ðCFIÞ ¼ 0.90, Tucker–Lewis index ðTLIÞ ¼ 0.89, and root mean square error of approximation ðRMSEAÞ ¼ 0.07]. Respondents were asked to rate on a five-point Likert-scale, where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. A sample item is: “My team members encourage me to rethink ideas that have never been questioned before,” α ¼ 0.91. Moderating Variable

- 33. Knowledge sharing is operationalized as the working environment in which employees share information for mobilizing their creative potential and use available information for optimal task solutions (Christensen 2007; Wang and Noe 2010). A six-item scale was adapted from Bock et al. (2005) to measure the degree to which individuals perceived their team members as sharing different forms of knowledge (Choi et al. 2010). This measure was previ - ously used in the project context by Park and Lee (2014). A five- point Likert scale was used, where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. A sample item is: “In the last project, we shared project plans and the project status in an effective way,” α ¼ 0.80. Mediating Variable Autonomy was measured by four items adapted from Lee and Xia (2010) based on earlier work of Breaugh (1985) and Zmud (1982). The scale measured all four facets of project autonomy— (1) goal defining, (2) social autonomy, (3) structural autonomy, and (4) resource autonomy (Gemünden et al. 2005)—and items were modified in the context of leadership and construction. A sample item is: “In my last project, my project manager was granted autonomy on how to handle user requirement changes,” α ¼ 0.76. Dependent Variable Project success has multiple angles in the literature, and no uniform approach exists (even in the project literature) to measure project success—and there is an ongoing debate as to what project success

- 34. means (Ika 2009; Todorović et al. 2015). Consistent with previous studies, this study takes a site engineer’s perspective and asks about the extent to which the project team is productive in its tasks and © ASCE 04021067-4 J. Constr. Eng. Manage. J. Constr. Eng. Manage., 2021, 147(7): 04021067 D ow nl oa de d fr om a sc el ib ra ry .o rg b

- 37. ri gh ts r es er ve d. effective in its interactions with nonteam members (Bryde 2008; Khang and Moe 2008; Mir and Pinnington 2014; Pinto and Pinto 1990), and a composite measure of a multidimensional construct of project success (cost, client use, effectiveness, satisfaction, perfor- mance, and time management) with 14 items (Aga et al. 2016) was created. A five-point Likert scale was used to record responses, where 1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree. A sample item is: “The last project was completed in compliance with the budget allocated,” α ¼ 0.92. Common-Method Bias The author employed a rigorous approach to reduce common- method bias. For example, temporal separation was performed dur- ing data collection, with respondent anonymity, and no wrong and right answers were communicated to participants (Podsakoff et

- 38. al. 2012, p. 888). However, because the data were collected from the same source, the chances of common-method bias may still exist. Thus, a recommended post hoc latent factor approach was used to detect the presence of common-method bias (Chang et al. 2010, p. 181; Conway and Lance 2010, p. 331; Williams and Anderson 1994). The results of the unconstrained model (X2 ¼ 2,692.68, df ¼ 1,120; p ¼ not significant, and ΔX2 and Δdf remained zero) demonstrated the nonexistence of bias affecting the hypothesized model (Gaskin and Lim 2017). Therefore, there is no threat of common-method bias. Results of Correlations and Discriminant Validity Table 1 shows descriptive statistics and zero-order correlation where shared leadership was positive and significantly related to autonomy (r ¼ 0.63, p < 0.01), knowledge sharing (r ¼ 0.68, p < 0.01), and project success (r ¼ 0.60, p < 0.01). Likewise, autonomy and KS are positively linked with project success. A confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to analyze the fit be- tween the hypothesized model and the data. Table 2 indicates that a four-factor hypothesized model was a better fit [X2 ¼ 646.57, df ¼ 392, RMSEA ¼ 0.05, root mean square residual ðRMRÞ ¼ 0.05, TLI ¼ 0.93, CFI ¼ 0.93] than all three rival models and achieved sufficient discriminant validity. Analytical Strategy and Hypothesis Testing

- 39. The PROCESS Macro developed by Hayes was used to test the direct, indirect, and moderation for two reasons: first, researchers suggested that the PROCESS Macro algorithm produ- ces similar results to structural equation modeling (Hayes et al. 2017); second, it requires limited skill to do complex analysis — even with two (or more) mediators and moderators in one model at the same time (Hayes 2017). Regardless of the number of equa- tions in a model, PROCESS Macro estimates each equation sepa- rately and “estimation of the regression parameters in one of the equations has no effect on the estimation of the parameters in any other equations defining the model” (Hayes et al. 2017, p. 77). PROCESS Model 7 was used to test the direct, indirect, and first stage moderating hypotheses. Table 3 shows direct path results that shared leadership was positively related to project success [β ¼ 0.35, standard error ðSEÞ ¼ 0.07, t ¼ 5.40, 95% confidence interval (CI), lower limit confidence interval ðLLCIÞ ¼ 0.22, upper limit confidence interval ðULCIÞ ¼ 0.48], supporting Hypothesis 1. The second hypothesis states that autonomy mediates the rela- tionship between shared leadership and project success (effect ¼ 0.22, SE ¼ 0.05, 95% CI, LLCI ¼ 0.12; ULCL ¼ 0.33), support- ing Hypothesis 2. Table 4 shows that the complete results of condi- tional indirect effects remained significant on all three levels. The

- 40. third hypothesis states that KS moderates the relationship between shared leadership and autonomy. The results of the interaction effect in Table 5 revealed that members felt more autonomy fos - tered by a shared leader when knowledge sharing is high, and vice versa (effectsize ¼ 0.29, t ¼ 4.04, 95% CI, LLCI ¼ 0.15, ULCI ¼ 0.44), supporting hypothesis 3. Further, a slope test was performed to visually inspect the trend of interaction (shared leadership × knowledge sharing → autonomy) (Aiken et al. 1991). The dotted line in Fig. 2 shows a clear interaction effect, that the project team member experienced a higher degree of autonomy when shared leadership and knowledge sharing were high, in contrast to the plain line, where Table 1. Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations S. No. Variable Mean SD 1 2 3 4 1 Shared leadership 4.05 0.64 (0.91) — — — 2 Autonomy 4.08 0.79 0.63a (0.76) — — 3 Knowledge sharing 4.16 0.64 0.68a 0.57a (0.80) — 4 Project success 4.17 0.64 0.60a 0.61a 0.58a (0.92) Note: N ¼ 216. ap < 0.01, alpha value in parentheses. SD = standard deviation. Table 2. Discriminant validity (model fit) Model CMIN df RMSEA RMR TLI CFI Four-factor (hypothesized) 646.57 392 0.05 0.05 0.93 0.93

- 41. Rival model 1 (combined KS and Autonomy) 789.32 395 0.07 0.06 0.89 0.90 Rival Model 2 (combined KS, autonomy, and PS) 870.97 397 0.07 0.06 0.86 0.88 Rival Model 3 (combined all) 985.3 398 0.08 0.06 0.83 0.85 Note: N ¼ 216; KS = knowledge sharing; PS = project success; RMR = root mean square residual; and CMIN = chi-square minimum. Table 3. Direct and indirect effect Direct effect (shared leadership → project success) Effect SE p-value 95% confidence interval LLCI ULCI 0.35 0.07 0.000 0.22 0.48 Note: LLCI = lower limit confidence interval; ULCI = upper limit confidence interval; and SE = standard error. © ASCE 04021067-5 J. Constr. Eng. Manage. J. Constr. Eng. Manage., 2021, 147(7): 04021067 D ow nl oa

- 44. or p er so na l us e on ly ; al l ri gh ts r es er ve d. the team member experienced low autonomy due to low

- 45. knowledge sharing. Discussion and Implications This study examined the role of shared leadership in a construction project and how shared leadership leverages members’ autonomy to amplify the success of construction projects. The primary objec- tive was to take the construction industry as an example because it is directly linked with social and economic development to achieve resource efficiency and meet sustainable development goals (Ahmad et al. 2020). From a project standpoint, this study highlighted that shared leadership leverages autonomy, which in- creases team members’ power to cope with project challenges (Hoegl and Muethel 2016), and that members willfully accomplish tasks (Huang 2013). This study used the theoretical lens of self-determination theory and highlighted that shared leadership is not merely a style but po- tentially an emergent property of construction teams, because in such a scenario leaders fulfill members’ psychological needs by promoting autonomy and knowledge sharing (Clarke 2012). Con- struction projects—particularly small- to medium-sized projects— usually have an appointed project manager to communicate project goals, objectives, and deliverables, and the appointed manager must get work done through members because they hold diverse skill sets (e.g., design understanding, roofing, and sheet metal

- 46. work). In situations where dependence on team members is high, a shared leadership approach with empowered members creates a synergy for achieving overall project goals. This study highlighted that, in construction projects, when members perceive equal roles and responsibilities for delivering project outcomes, they are mo- tivated to obtain collective guidance from one another with every possible alternative (Fausing et al. 2015). Therefore, to achieve satisfactory results from members, construction project managers should grant equal importance to the human aspects of projects, along with their technical aspects. Owing to budgetary constraints in small- and medium-sized projects, it is difficult to offer monetary rewards to all project workers and keep them motivated. Therefore, this study highlighted that self-motivation is a suitable alternative to monetary rewards that can be achieved through shared leadership (Deci and Ryan 2000; Odusami et al. 2003). Based on US data, McKinsey & Company (2015, p. 5) high- lighted that the construction industry is highly labor-intensive, with the lowest usage of digitization and communication technologies compared to other industries (e.g., information and communication technology, media, or professional services). In the absence (or

- 47. low level) of digitization in a project, shared leadership better serves the purpose of managing distributed functions and heterogeneous teams (Clarke 2012), because any change in design, material, or project scope should be discussed in a shared manner among mem- bers, increasing their confidence and improving team functioning (Bourgault et al. 2008). Likewise, this study further indicated that shared leadership on projects provides a culture of information sharing to expand workers’ skills (Scarbrough et al. 2004) and to better communicate an organization’s vision (Plakhotnik et al. 2011). By enhancing members’ existing knowledge, skills, and abilities, members remain self-motivated and able to respond to un- certain situations that are crucial to attaining project goals (Ryan and Deci 2000). In recent years, the construction industry in Pakistan has at- tracted foreign direct investment, and this study has provided a way for construction organizations to recognize that leadership is an important factor in reducing project failure and meeting the ex- pectations of stakeholders through project teams (Gazder and Khan 2018). National culture was not the main focus of this study, but the application of a particular leadership style in different cultures is crucial in achieving positive outcomes. For example, a

- 48. leadership style that is applied in Western culture may not produce the same results that it would in Asian culture (Liden 2012; Suen et al. 2007). Pakistan has a culture with a high sense of collectivism and power distance, in which leaders maintain social distance from subordi- nates, and subordinates also obey a strict hierarchy (Hofstede 2001). This study highlighted that applying shared leadership in construction projects may bring positive results; however, this can- not be generalized in megaprojects since this study used a sample from medium-sized construction projects, but it suggests a potential avenue for future research with samples taken from megaprojects. This study also highlighted that a leadership style introduced in Western countries is equally (or more) beneficial in non- Western countries (Lee et al. 2020). However, future researchers can take Table 4. Conditional indirect effect Shared leadership → autonomy → project success Knowledge sharing Boot indirect effect Boot SE LLCI ULCI −1 SD (−0.65) 0.14 0.06 0.06 0.27 Mean (0) 0.22 0.05 0.12 0.33 þ1 SD (0.68) 0.26 0.06 0.14 0.39 Note: A second analysis was performed while controlling for gender.

- 49. The results of the direct and moderating effects remained the same, but the conditional indirect effect was improved on all three levels: SD (−1) = 0.46, mean (0) = 0.69, and SD ðþ1Þ ¼ 0.83. In a third analysis, experience and gender were used as controls and all the results were similar, as reported in the main text. LLCI = lower limit confidence interval; ULCI = upper limit confidence interval; and SE = standard error. Table 5. Moderating effect of knowledge sharing Antecedent Autonomy Coefficient value SE p-value Shared leadership 0.65 0.09 0.00 Knowledge sharing 0.37 0.08 0.00 Shared leadership × knowledge sharing 0.29 0.07 0.00 Note: N ¼ 216; and SE = standard error. 1 1.5 2 2.5

- 50. 3 3.5 4 4.5 5 Low Shared Leadership High Shared Leadership A ut on om y Low Knowledge sharing High Knowledge sharing Slope analysis Fig. 2. Slope analysis. © ASCE 04021067-6 J. Constr. Eng. Manage. J. Constr. Eng. Manage., 2021, 147(7): 04021067 D ow nl oa

- 53. or p er so na l us e on ly ; al l ri gh ts r es er ve d. cultural aspects into consideration in order to provide greater in-

- 54. sight into shared leadership and project functioning, and propose more localized project solutions. This study contributed to the literature in several ways. First, concepts such as leadership, commitment, and identification are well studied in the organizational psychology literature but are hardly studied in the project context (Byrne and Barling 2015; Tremblay et al. 2015). Research on contemporary leadership styles may provide benefits in terms of gaining better control over projects, and this study highlighted the role of shared leadershi p in construction projects in response to the recent call for research on project leadership (Scott-Young et al. 2019). The present work also discussed a KS environment as a boundary condition that expands project workers’ skills (Nicolaides et al. 2014) and reduces asym- metry in existing (yet mixed) findings in which the interaction of shared leadership and autonomy lowers team performance (Fausing et al. 2013) and individual satisfaction (Robert and You 2018). The present study’s framework deepens the understanding of medium-sized construction projects with self-determination theory, that shared leadership fulfills workers’ psychological needs (competence, relatedness, and autonomy) and helps in achieving project deliverables (Deci and Ryan 2000). This study applied a multifaceted project success approach and highlighted that shared leadership is not limited to one dimension of project success but positively impacts project cost, client use, effectiveness,

- 55. satisfac- tion, performance, and covering time (Aga et al. 2016). In addition, this study confirms that a single individual may not perform all the leadership functions effectively, but “within a project, there may be a set of individuals who collectively perform this activity” (Clarke 2012, p. 198). Limitation and Future Research Directions The results of this study should be taken with caution. Several precautions were put in place to minimize common-method bias during data collection, and then statistical remedies (i.e., latent method factor and confirmatory factor analysis) were used, as suggested by Podsakoff et al. (2003): first, the data were collected on two time points to reduce the consistency motifs and demand characteristics; second, confidentiality of respondents (along with no right and wrong answers to survey questions) was communi- cated to reduce the social desirability; third, items of each scale were placed in random order to decrease any priming effect; and lastly, the questionnaire was pretested to check its validity and reliability—but that still does not justify claims of a causal relation. Therefore, a longitudinal and multilevel study (with client re- sponse about the project delivered) would bring about a better understanding of the nexus of shared leadership and project success (Scott-Young et al. 2019). This study took the perspective of perceived autonomy and knowledge sharing to expand individual skill sets of

- 56. construction workers; however, perceived competence is also necessary for in- trinsic motivation, and it would be interesting for future researchers to see how perceived autonomy leveraged by shared leadership strengthened the perceived competence, along with how it adds to the team functioning (Deci and Ryan 2000). This could be done through parallel mediation, where one can assess the stronger mediator between autonomy and competence through contrast analysis. Another possibility exists: testing the former through serial mediation, where autonomy leads to competence. This study did not address the well-being perspective, which is also im- portant in construction projects to obtain optimal output from workers. A recent study in construction highlighted that autonomy is negatively affected when workers have work-family conflict, and this impacts not only individual family life but also work outcomes (Bowen and Zhang 2020). Thus, investigating workers’ psycho- logical well-being in the context of a construction project would be an interesting line of future research. The present study was descriptive in nature and aimed to understand the role of shared leadership in construction project success via autonomy and knowl- edge sharing as a boundary condition. However, a comparative study—particularly from the perspective of workers’ psychological needs—will help project managers better understand the extent to which shared leadership adds to the technical aspects of construc-

- 57. tion projects (i.e., budgeting, planning, risk management, schedul- ing, safety, and so on) and team property compared to other styles of leadership, such as authoritarian, authentic, or transformational (Imam et al. 2020). Team size is another important factor in project leadership (particularly in mega construction projects, where team size is typically large). It would be interesting to investigate how team size impacts the effectiveness of shared leadership in project outcomes. Conclusion Leadership is one of the most mature fields in organizational studies, and yet the role of project leadership remains an under - developed area of study. Project functions require a cooperative approach to carry out tasks efficiently, and shared leadership may be a suitable alternative to vertical leadership. The present study was limited to construction projects but provides evidence for how project leadership effects occur in a systemic manner. Management should, however, assign the project manager’s responsibilities to someone who has a personality to share the leadership role when required. A positive leadership role always motivates construction workers to devote their best effort to as- signed tasks. Overall, this study concludes that the human side of projects is equally significant for studying and contributing to project success. Data Availability Statement

- 58. Some or all data, models, or code that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Acknowledgments I would like to thank Mr. Kashif Zaheer, Lab Technologist at Punjab Tianjin University of Technology, Lahore, for his continu- ous support and assistance with data collection. References Aga, D. A., N. Noorderhaven, and B. Vallejo. 2016. “Transformational leadership and project success: The mediating role of team- building.” Int. J. Project Manage. 34 (5): 806–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j .ijproman.2016.02.012. Ahmad, S. B. S., M. U. Mazhar, A. Bruland, B. S. Andersen, J. A. Langlo, and O. Torp. 2020. “Labour productivity statistics: A reality check for the Norwegian construction industry.” Int. J. Constr. Manage. 20 (1): 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 15623599.2018.1462443. Aiken, L. S., S. G. West, and R. R. Reno. 1991. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. New York: SAGE.

- 59. © ASCE 04021067-7 J. Constr. Eng. Manage. J. Constr. Eng. Manage., 2021, 147(7): 04021067 D ow nl oa de d fr om a sc el ib ra ry .o rg b y A ra b A

- 62. er ve d. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2016.02.012 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2016.02.012 https://doi.org/10.1080/15623599.2018.1462443 Al-Bahar, J. F., and K. C. Crandall. 1990. “Systematic risk management approach for construction projects.” J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 116 (3): 533–546. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733- 9364(1990) 116:3(533). Ashley, S. 1992. “US quality improves but Japan still leads.” Mech. Eng.-CIME 114 (12): 24–26. Bock, G.-W., R. W. Zmud, Y.-G. Kim, and J.-N. Lee. 2005. “Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate.” MIS Q. 29 (1): 87–111. https://doi.org/10.2307/25148669. Bourgault, M., N. Drouin, and É. Hamel. 2008. “Decision making within distributed project teams: An exploration of formalization and autonomy as determinants of success.” Supplement, Project Manage.

- 63. J. 39 (S1): S97–S110. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmj.20063. Bowen, P., and R. P. Zhang. 2020. “Cross-boundary contact, work-family conflict, antecedents, and consequences: Testing an integrated model for construction professionals.” J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 146 (3): 04020005. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)CO.1943- 7862.0001784. Breaugh, J. A. 1985. “The measurement of work autonomy.” Hum. Relat. 38 (6): 551–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872678503800604. Brislin, R. W. 1970. “Back-translation for cross-cultural research.” J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 1 (3): 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177 /135910457000100301. Bryde, D. 2008. “Perceptions of the impact of project sponsorship practices on project success.” Int. J. Project Manage. 26 (8): 800–809. https://doi .org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2007.12.001. Burke, C. S., S. M. Fiore, and E. Salas. 2003. “The role of shared cognition in enabling shared leadership and team adaptability.” In Shared lead- ership: Reframing the hows and whys of leadership, edited by C. L. Pearce and J. A. Conger, 103–122. New York: SAGE. Byrne, A., and J. Barling. 2015. “Leadership and project teams.” In The

- 64. psychology and management of project teams, edited by F. C. Kelloway and B. Hobbs, 137–163. New York: Oxford University Press. Byrne, J. 1999. “Project management: How much is enough?” PM Network 13 (2): 49–54. Carson, J. B., P. E. Tesluk, and J. A. Marrone. 2007. “Shared leadership in teams: An investigation of antecedent conditions and performance.” Acad. Manage. J. 50 (5): 1217–1234. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj .2007.20159921. Chan, A. T., and E. H. Chan. 2005. “Impact of perceived leadership styles on work outcomes: Case of building professionals.” J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 131 (4): 413–422. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364 (2005)131:4(413). Chang, S.-J., A. Van Witteloostuijn, and L. Eden. 2010. “From the editors: Common method variance in international business research.” J. Int. Bus. Stud. 41 (2): 178–184. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.88. Chiniara, M., and K. Bentein. 2016. “Linking servant leadership to indi- vidual performance: Differentiating the mediating role of autonomy, competence and relatedness need satisfaction.” Leadersh. Q. 27

- 65. (1): 124–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.08.004. Choi, S. Y., H. Lee, and Y. Yoo. 2010. “The impact of information technology and transactive memory systems on knowledge sharing, application, and team performance: A field study.” MIS Q. 34 (4): 855–870. https://doi.org/10.2307/25750708. Christensen, P. H. 2007. “Knowledge sharing: Moving away from the obsession with best practices.” J. Knowl. Manage. 11 (1): 36– 47. https://doi.org/10.1108/13673270710728222. Clarke, N. 2012. “Shared leadership in projects: A matter of substance over style.” Team Perform. Manage. Int. J. 18 (3/4): 196–209. https://doi.org /10.1108/13527591211241024. Conger, J. A., and C. L. Pearce. 2003. “A landscape of opportunities: Future research on shared leadership.” In Shared leadership: Reframing the hows and whys of leadership, edited by C. L. Pearce and J. A. Conger, 285–304. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Conway, J. M., and C. E. Lance. 2010. “What reviewers should expect from authors regarding common method bias in organizational research.” J. Bus. Psychol. 25 (3): 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-010

- 66. -9181-6. Coun, M. M., P. C. Peters, and R. R. Blomme. 2019. “‘Let’s share!’ The mediating role of employees’ self-determination in the relationship between transformational and shared leadership and perceived knowl- edge sharing among peers.” Eur. Manage. J. 37 (4): 481–491. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2018.12.001. Crevani, L., M. Lindgren, and J. Packendorff. 2007. “Shared leadership: A post-heroic perspective on leadership as a collective construction.” Int. J. Leadersh. Stud. 3 (1): 40–67. Dainty, A. R., A. Bryman, and A. D. Price. 2002. “Empowerment within the UK construction sector.” Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 23 (6): 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730210441292. Deci, E. L., and R. M. Ryan. 2000. “The ‘what’ and ‘why’ of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior.” Psychol. Inq. 11 (4): 227–268. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_01. De Cooman, R., D. Stynen, A. Van den Broeck, L. Sels, and H. De Witte. 2013. “How job characteristics relate to need satisfaction and autono-

- 67. mous motivation: Implications for work effort.” J. Appl. Social Psychol. 43 (6): 1342–1352. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12143. De Vaus, D. 2013. Surveys in social research. 6th ed. London: Routledge. Drescher, M. A., M. A. Korsgaard, I. M. Welpe, A. Picot, and R. T. Wigand. 2014. “The dynamics of shared leadership: Building trust and enhanc- ing performance.” J. Appl. Psychol. 99 (5): 771. https://doi.org/10.1037 /a0036474. Ellerman, D. 2004. “Autonomy-respecting assistance: Toward an alterna- tive theory of development assistance.” Rev. Social Econ. 62 (2): 149–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346760410001684424. Ellerman, D. 2009. Helping people help themselves: From the World Bank to an alternative philosophy of development assistance. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. Ensley, M. D., K. M. Hmieleski, and C. L. Pearce. 2006. “The importance of vertical and shared leadership within new venture top management teams: Implications for the performance of startups.” Leadersh. Q. 17 (3): 217–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.02.002. Fausing, M. S., H. J. Jeppesen, T. S. Jønsson, J. Lewandowski,

- 68. and M. C. Bligh. 2013. “Moderators of shared leadership: Work function and team autonomy.” Team Perform. Manage. Int. J. 19 (5/6): 244–262. https:// doi.org/10.1108/TPM-11-2012-0038. Fausing, M. S., T. S. Joensson, J. Lewandowski, and M. Bligh. 2015. “Antecedents of shared leadership: Empowering leadership and inter- dependence.” Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 36 (3): 271–291. https://doi .org/10.1108/LODJ-06-2013-0075. Fernet, C., M. Gagné, and S. Austin. 2010. “When does quality of relation- ships with coworkers predict burnout over time? The moderating role of work motivation.” J. Organ. Behav. 31 (8): 1163–1180. https://doi.org /10.1002/job.673. Fletcher, J. K., and K. Kaufer. 2003. “Shared leadership: Paradox and pos- sibility.” In Shared leadership: Reframing the hows and whys of lead- ership, edited by C. L. Pearce, J. A. Conger, 21–47. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. https://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781452229539.n2. Fong, P. S., and B. W. Lung. 2007. “Interorganizational teamwork in the construction industry.” J. Constr. Eng. Manage. 133 (2): 157– 168. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(2007)133:2(157).

- 69. Fulford, R., and C. Standing. 2014. “Construction industry productivity and the potential for collaborative practice.” Int. J. Project Manage. 32 (2): 315–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2013.05.007. Gagné, M. 2003. “The role of autonomy support and autonomy orientation in prosocial behavior engagement.” Motivation Emotion 27 (3): 199–223. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025007614869. Gaskin, J., and J. Lim. 2017. “CFA tool, AMOS plugin: Retrieved from Gaskination’s StatWiki.” Accessed January 25, 2020. http://statwiki .kolobkreations.com. Gazder, U., and R. Khan. 2018. “Effect of organizational structures and types of construction on perceptions of factors contributing to project failure in Pakistan.” Mehran Univ. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 37 (1): 127–138. https://doi.org/10.22581/muet1982.1801.11. Gemünden, H. G., S. Salomo, and A. Krieger. 2005. “The influence of project autonomy on project success.” Int. J. Project Manage. 23 (5): 366–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2005.03.004. Giritli, H., and G. T. Oraz. 2004. “Leadership styles: Some evidence from the Turkish construction industry.” Constr. Manage. Econ. 22 (3): 253–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446190310001630993.

- 70. © ASCE 04021067-8 J. Constr. Eng. Manage. J. Constr. Eng. Manage., 2021, 147(7): 04021067 D ow nl oa de d fr om a sc el ib ra ry .o rg b y A ra b

- 74. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346760410001684424 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.02.002 https://doi.org/10.1108/TPM-11-2012-0038 https://doi.org/10.1108/TPM-11-2012-0038 https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-06-2013-0075 https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-06-2013-0075 https://doi.org/10.1002/job.673 https://doi.org/10.1002/job.673 http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781452229539.n2 https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9364(2007)133:2(157) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2013.05.007 https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025007614869 http://statwiki.kolobkreations.com http://statwiki.kolobkreations.com https://doi.org/10.22581/muet1982.1801.11 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2005.03.004 https://doi.org/10.1080/01446190310001630993 Gupta, V. K., R. Huang, and S. Niranjan. 2010. “A longitudinal examina- tion of the relationship between team leadership and performance.” J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 17 (4): 335–350. https://doi.org/10.1177 /1548051809359184. Hauschildt, J., and E. Kirchmann. 2001. “Teamwork for innovation–the ‘troika’of promoters.” R&D Manage. 31 (1): 41–49. https://doi.org/10 .1111/1467-9310.00195. Hayes, A. F. 2017. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York:

- 75. Guilford Publications. Hayes, A. F., A. K. Montoya, and N. J. Rockwood. 2017. “The analysis of mechanisms and their contingencies: PROCESS versus structural equa- tion modeling.” Australas. Marketing J. 25 (1): 76–81. https://doi.org /10.1016/j.ausmj.2017.02.001. Hoch, J., J. Dulebohn, and C. Pearce. 2010. “Shared leadership question- naire (SLQ): Developing a short scale to measure shared and vertical leadership in teams.” In Proc., SIOP Conf. (Visual Presentation). Bowling Green, OH: Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Hoegl, M., and M. Muethel. 2016. “Enabling shared leadership in virtual project teams: A practitioners’ guide.” Project Manage. J. 47 (1): 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmj.21564. Hoegl, M., and A. Schulze. 2005. “How to support knowledge creation in new product development: An investigation of knowledge management methods.” Eur. Manage. J. 23 (3): 263–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j .emj.2005.04.004. Hofstede, G. 2001. Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors,

- 76. institutions and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Hollenbeck, J. R., B. Beersma, and M. E. Schouten. 2012. “Beyond team types and taxonomies: A dimensional scaling conceptualization for team description.” Acad. Manage. Rev. 37 (1): 82–106. https://doi .org/10.5465/amr.2010.0181. Holt, G. D., P. E. Love, and L. J. Nesan. 2000. “Employee empowerment in construction: An implementation model for process improvement.” Team Perform. Manage. Int. J. 6 (3–4): 47–51. https://doi.org/10 .1108/13527590010343007. Houghton, J. D., C. P. Neck, and C. C. Manz. 2003. “Self- leadership and superleadership: The heart and art of creating shared leadership in teams.” In Shared leadership: Reframing the hows and whys of lead- ership, edited by C. L. Pearce and J. A. Conger, 123–140. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Huang, C.-H. 2013. “Shared leadership and team learning: Roles of knowledge sharing and team characteristics.” J. Int. Manage. Stud. 8 (1): 124–133.

- 77. Ika, L. A. 2009. “Project success as a topic in project management journals.” Project Manage. J. 40 (4): 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmj .20137. Imam, H., M. B. Naqvi, S. A. Naqvi, and M. J. Chambel. 2020. “Authentic leadership: Unleashing employee creativity through empowerment and commitment to the supervisor.” Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 41 (6): 847–864. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-05-2019-0203. Imam, H., and M. K. Zaheer. 2021. “Shared leadership and project success: The roles of knowledge sharing, cohesion and trust in the team.” Int. J. Project Manage. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2021.02.006. Judge, W. Q., and J. A. Ryman. 2001. “The shared leadership challenge in strategic alliances: Lessons from the US healthcare industry.” Acad. Manage. Perspect. 15 (2): 71–79. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2001 .4614907. Khang, D. B., and T. L. Moe. 2008. “Success criteria and factors for international development projects: A life-cycle-based framework.” Project Manage. J. 39 (1): 72–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmj.20034. Kozlowski, S. W., S. M. Gully, E. Salas, and J. A. Cannon-

- 78. Bowers. 1996. “Team leadership and development: Theory, principles, and guidelines for training leaders and teams.” In Vol. 3 of Advances in interdiscipli- nary studies of work teams: Team leadership, edited by M. M. Beyerlein, D. A. Johnson, and S. T. Beyerlein, 253–291. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier. Kuenzel, R., J. Teizer, M. Mueller, and A. Blickle. 2016. “SmartSite: Intelligent and autonomous environments, machinery, and processes to realize smart road construction projects.” Autom. Constr. 71 (Nov): 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autcon.2016.03.012. Lee, A., J. Lyubovnikova, A. W. Tian, and C. Knight. 2020. “Servant leadership: A meta-analytic examination of incremental contribution, moderation, and mediation.” J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 93 (1): 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12265. Lee, G., and W. Xia. 2010. “Toward agile: An integrated analysis of quantitative and qualitative field data on software development agility.” MIS Q. 34 (1): 87–114. https://doi.org/10.2307/20721416. LePine, J. A., R. F. Piccolo, C. L. Jackson, J. E. Mathieu, and J. R. Saul. 2008. “A meta-analysis of teamwork processes: Tests of a

- 79. multidimen- sional model and relationships with team effectiveness criteria.” Person- nel Psychol. 61 (2): 273–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744- 6570.2008 .00114.x. Liden, R. C. 2012. “Leadership research in Asia: A brief assessment and suggestions for the future.” Asia Pac. J. Manage. 29 (2): 205– 212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-011-9276-2. Lord, R. G., D. V. Day, S. J. Zaccaro, B. J. Avolio, and A. H. Eagly. 2017. “Leadership in applied psychology: Three waves of theory and re- search.” J. Appl. Psychol. 102 (3): 434–451. https://doi.org/10.1037 /apl0000089. McKinsey & Company. 2015. “Digital America: A tale of the haves and haves-mores.” Accessed December 18, 2019. https://www.mckinsey .com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Technology%20Media%20a nd%20 Telecommunications/High%20Tech/Our%20Insights/Digital%20 America %20A%20tale%20of%20the%20haves%20and%20have%20more s/MGI %20Digital%20America_Executive%20Summary_December%20 2015 .ashx. Millette, V., and M. Gagné. 2008. “Designing volunteers’ tasks

- 80. to maximize motivation, satisfaction and performance: The impact of job characteristics on volunteer engagement.” Motivation Emotion 32 (1): 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-007-9079-4. Mir, F. A., and A. H. Pinnington. 2014. “Exploring the value of project management: Linking project management performance and project success.” Int. J. Project Manage. 32 (2): 202–217. https://doi.org/10 .1016/j.ijproman.2013.05.012. Müller, R., and R. Turner. 2007. “The influence of project managers on project success criteria and project success by type of project.” Eur. Manage. J. 25 (4): 298–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2007 .06.003. Muñiz Castillo, M. R., and D. Gasper. 2012. “Human autonomy effective- ness and development projects.” Oxford Dev. Stud. 40 (1): 49– 67. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2011.646975. Nicolaides, V. C., K. A. LaPort, T. R. Chen, A. J. Tomassetti, E. J. Weis, S. J. Zaccaro, and J. M. Cortina. 2014. “The shared leadership of teams: A meta-analysis of proximal, distal, and moderating relationships.” Leadersh. Q. 25 (5): 923–942.

- 81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2014 .06.006. Nixon, P., M. Harrington, and D. Parker. 2012. “Leadership performance is significant to project success or failure: A critical analysis.” Int. J. Pro- ductivity Perform. Manage. 61 (2): 204–216. https://doi.org/10.1108 /17410401211194699. Odusami, K., R. Iyagba, and M. Omirin. 2003. “The relationship between project leadership, team composition and construction project perfor- mance in Nigeria.” Int. J. Project Manage. 21 (7): 519–527. https://doi .org/10.1016/S0263-7863(02)00059-5. Park, J. G., and J. Lee. 2014. “Knowledge sharing in information systems development projects: Explicating the role of dependence and trust.” Int. J. Project Manage. 32 (1): 153–165. Pearce, C. L., and J. A. Conger. 2003. “All those years ago: The historical underpinnings of shared leadership.” In Shared leadership: Reframing the hows and whys of leadership, edited by C. L. Pearce and J. A. Conger, 1–18. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. Pearce, C. L., and P. A. Herbik. 2004. “Citizenship behavior at the team level of analysis: The effects of team leadership, team

- 82. commitment, perceived team support, and team size.” J. Social Psychol. 144 (3): 293–310. https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.144.3.293-310. Pearce, C. L., and C. C. Manz. 2005. “The new silver bullets of leadership: The importance of self-and shared leadership in knowledge work.” © ASCE 04021067-9 J. Constr. Eng. Manage. J. Constr. Eng. Manage., 2021, 147(7): 04021067 D ow nl oa de d fr om a sc el ib ra ry .o

- 87. %20haves%20and%20have%20mores/MGI%20Digital%20Ameri ca_Executive%20Summary_December%202015.as hx https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-007-9079-4 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2013.05.012 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2013.05.012 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2007.06.003 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2007.06.003 https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2011.646975 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.06.006 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2014.06.006 https://doi.org/10.1108/17410401211194699 https://doi.org/10.1108/17410401211194699 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0263-7863(02)00059-5 https://doi.org/10.1016/S0263-7863(02)00059-5 https://doi.org/10.3200/SOCP.144.3.293-310 Organ. Dyn. 34 (2): 130–140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2005.03 .003. Pearce, C. L., and H. P. Sims, Jr. 2002. “Vertical versus shared leadership as predictors of the effectiveness of change management teams: An examination of aversive, directive, transactional, transformational, and empowering leader behaviors.” Group Dyn. Theory Res. Pract. 6 (2): 172–197. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.6.2.172. Phua, F. T. 2012. “Do national cultural differences affect the nature and characteristics of HRM practices? Evidence from Australian and Hong Kong construction firms on remuneration and job autonomy.”

- 88. Constr. Manage. Econ. 30 (7): 545–556. https://doi.org/10.1080 /01446193.2012.682074. Phua, F. T. 2013. “Construction management research at the individual level of analysis: Current status, gaps and future directions.” Constr. Manage. Econ. 31 (2): 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/01446193 .2012.707325. Pinto, J. K. 2000. “Understanding the role of politics in successful project management.” Int. J. Project Manage. 18 (2): 85–91. https://doi.org/10 .1016/S0263-7863(98)00073-8. Pinto, M. B., and J. K. Pinto. 1990. “Project team communication and cross-functional cooperation in new program development.” J. Product Innovation Manage. Int. Publ. Prod. Dev. Manage. Assoc. 7 (3): 200–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5885.730200. Plakhotnik, M. S., T. S. Rocco, and N. A. Roberts. 2011. “Development review integrative literature review: Increasing retention and success of first-time managers: A model of three integral processes for the transition to management.” Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 10 (1): 26– 45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484310386752. Podsakoff, P. M., S. B. MacKenzie, J.-Y. Lee, and N. P. Podsakoff. 2003.

- 89. “Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies.” J. Appl. Psychol. 88 (5): 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. Podsakoff, P. M., S. B. MacKenzie, and N. P. Podsakoff. 2012. “Sources of method bias in social science research and recommendations on how to control it.” Ann. Rev. Psychol. 63: 539–569. https://doi.org/10.1146 /annurev-psych-120710-100452. Printy, S. M., and H. M. Marks. 2006. “Shared leadership for teacher and student learning.” Theory Pract. 45 (2): 125–132. https://doi.org/10 .1207/s15430421tip4502_4. Robert, L. P. 2013. “A multi-level analysis of the impact of shared leadership in diverse virtual teams.” In Proc., 2013 Conf. on Computer Supported Cooperative Work. New York: Association for Computer Machinery. https://doi.org/10.1145/2441776.2441818. Robert, L. P., Jr., and S. You. 2018. “Are you satisfied yet? Shared lead- ership, individual trust, autonomy, and satisfaction in virtual teams.” J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 69 (4): 503–513. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi .23983.

- 90. Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2000. “Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being.” Am. Psychol. 55 (1): 68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003- 066X.55.1.68. Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2017. Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: Guilford Publications. Scarbrough, H., J. Swan, S. Laurent, M. Bresnen, L. Edelman, and S. Newell. 2004. “Project-based learning and the role of learning boundaries.” Organ. Stud. 25 (9): 1579–1600. https://doi.org/10.1177 /0170840604048001. Scott-Young, C. M., M. Georgy, and A. Grisinger. 2019. “Shared leadership in project teams: An integrative multi-level conceptual model and re- search agenda.” Int. J. Project Manage. 37 (4): 565–581. https://doi .org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2019.02.002. Silver, M. L. 1990. “Rethinking craft administration: Managerial position, work autonomy, and employment security in the building trades.” Sociological Forum 5 (2): 241–260. https://doi.org/10.1007 /BF01112594. Spatz, D. M. 1999. “Leadership in the construction industry.”

- 91. Pract. Period. Struct. Des. Constr. 4 (2): 64–68. https://doi.org/10.1061 /(ASCE)1084-0680(1999)4:2(64). Suen, H., S.-O. Cheung, and R. Mondejar. 2007. “Managing ethical behaviour in construction organizations in Asia: How do the teachings of Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism and Globalization influence ethics management?” Int. J. Project Manage. 25 (3): 257–265. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2006.08.001. Sun, M., and X. Meng. 2009. “Taxonomy for change causes and effects in construction projects.” Int. J. Project Manage. 27 (6): 560–572. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2008.10.005. Swart, J., and N. Kinnie. 2003. “Sharing knowledge in knowledge- intensive firms.” Hum. Resour. Manage. J. 13 (2): 60–75. https://doi .org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2003.tb00091.x. Todorović, M. L., D. Č. Petrović, M. M. Mihić, V. L. Obradović, and S. D. Bushuyev. 2015. “Project success analysis framework: A knowledge- based approach in project management.” Int. J. Project Manage. 33 (4): 772–783. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2014.10.009. Toor, S.-U.-R., and G. Ofori. 2008a. “Developing construction

- 92. professio- nals of the 21st century: Renewed vision for leadership.” J. Civ. Eng. Educ. 134 (3): 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1052- 3928 (2008)134:3(279). Toor, S.-U.-R., and G. Ofori. 2008b. “Leadership for future construction industry: Agenda for authentic leadership.” Int. J. Project Manage. 26 (6): 620–630. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijproman.2007.09.010. Tremblay, I., H. Lee, F. Chiocchio, and J. P. Meyer. 2015. “Identification and commitment in project teams.” In The psychology and management of project teams, edited by F. C. Kelloway and B. Hobbs, 189– 212. New York: Oxford University Press. Turner, J. R., and R. A. Cochrane. 1993. “Goals-and-methods matrix: Coping with projects with ill defined goals and/or methods of achieving them.” Int. J. Project Manage. 11 (2): 93–102. https://doi.org/10.1016 /0263-7863(93)90017-H. Turner, J. R., and R. Müller. 2005. “The project manager’s leadership style as a success factor on projects: A literature review.” Project Manage. J. 36 (2): 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/875697280503600206.

- 93. van Zijl, A. L., B. Vermeeren, F. Koster, and B. Steijn. 2019. “Towards sustainable local welfare systems: The effects of functional hetero- geneity and team autonomy on team processes in Dutch neighbourhood teams.” Health Social Care Community 27 (1): 82–92. https://doi.org /10.1111/hsc.12604. Vrijhoef, R., and L. Koskela. 2005. “Structural and contextual comparison of construction to other project-based industries.” In Vol. 2 of Proc., IPRC, 537–548. Salford, UK: Univ. of Salford. Walker, A. 2011. Organizational behaviour in construction. New York: Wiley. Wang, D., D. A. Waldman, and Z. Zhang. 2014. “A meta- analysis of shared leadership and team effectiveness.” J. Appl. Psychol. 99 (2): 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034531. Wang, S., and R. A. Noe. 2010. “Knowledge sharing: A review and direc- tions for future research.” Hum. Resour. Manage. Rev. 20 (2): 115–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2009.10.001. Williams, L. J., and S. E. Anderson. 1994. “An alternative approach to method effects by using latent-variable models: Applications in organi-

- 94. zational behavior research.” J. Appl. Psychol. 79 (3): 323–331. https:// doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.79.3.323. Worley, C. G., and E. E. Lawler, III. 2006. “Designing organizations that are built to change.” MIT Sloan Manage. Rev. 48 (1): 19–23. Yang, J.-B., and P.-R. Wei. 2010. “Causes of delay in the planning and design phases for construction projects.” J. Archit. Eng. 16 (2): 80–83. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1076-0431(2010)16:2(80). Zmud, R. W. 1982. “Diffusion of modern software practices: Influence of centralization and formalization.” Manage. Sci. 28 (12): 1421– 1431. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.28.12.1421. © ASCE 04021067-10 J. Constr. Eng. Manage. J. Constr. Eng. Manage., 2021, 147(7): 04021067 D ow nl oa de d fr om

- 99. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.79.3.323 https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1076-0431(2010)16:2(80) https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.28.12.1421 Summary of Roles of Shared Leadership, Autonomy, andKnowledge Sharing in Construction Project Success ABSTRACT RESULTS INTRODUCTION Hassan Imam, Ph.D. METHODS SUMMARY CONCLUSIONS REFERENCES Click to Add text 1