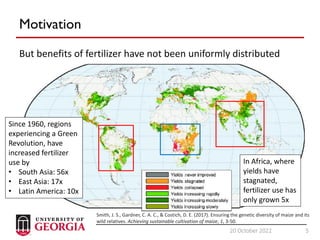

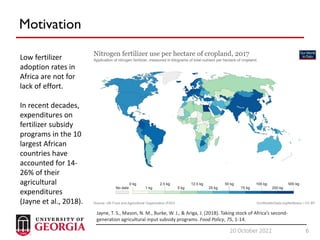

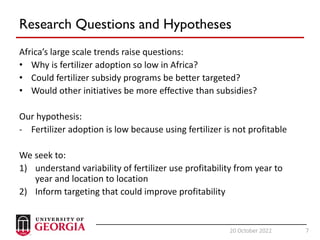

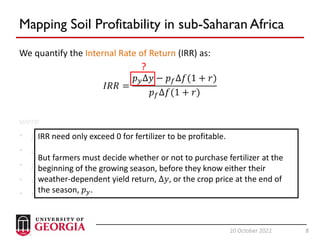

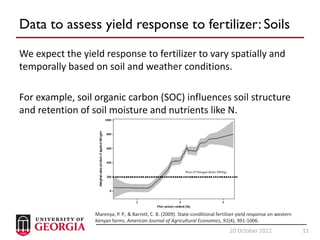

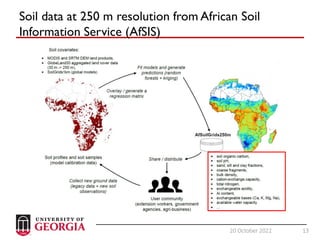

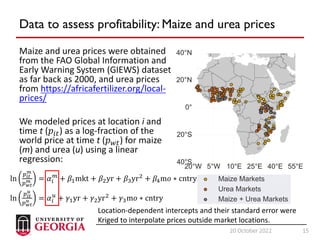

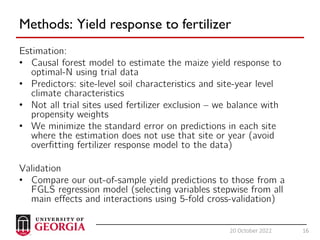

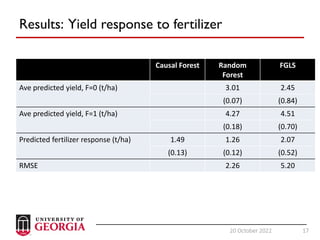

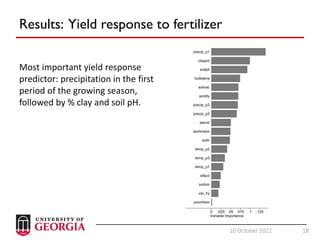

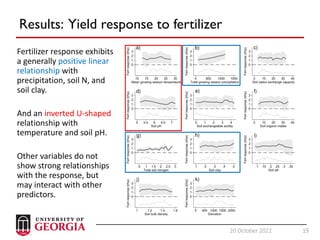

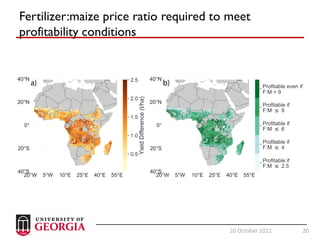

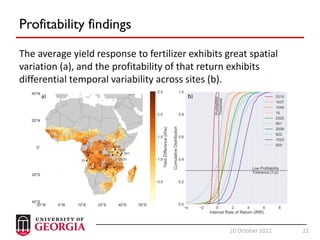

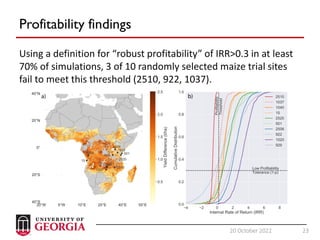

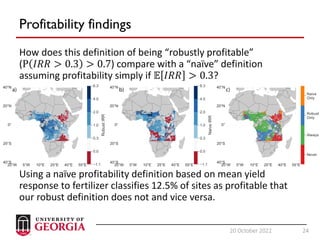

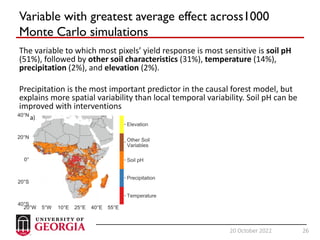

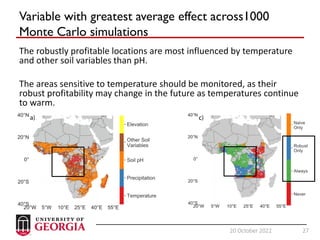

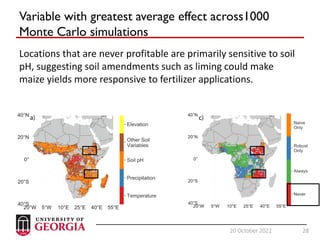

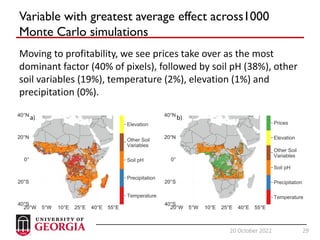

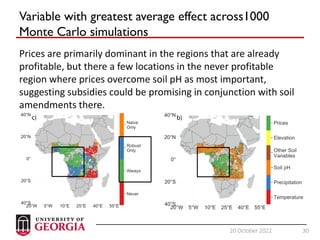

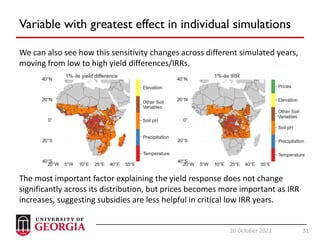

This paper models the profitability of fertilizer use for maize farmers in sub-Saharan Africa. It uses yield trial and soil data to estimate yield responses to fertilizer across different soil and climate conditions. It then simulates profitability over 1,000 years using historical weather and price data to identify areas where fertilizer use is robustly profitable in at least 70% of years. The analysis finds great spatial variation in yield responses and profitability. Soil pH has the largest effect on both, suggesting soil amendments could improve fertilizer adoption more than subsidies which are most effective in already profitable areas.