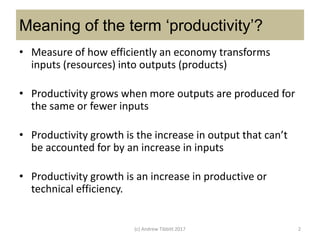

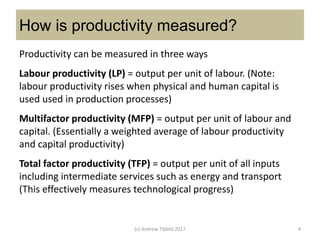

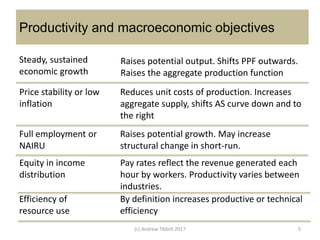

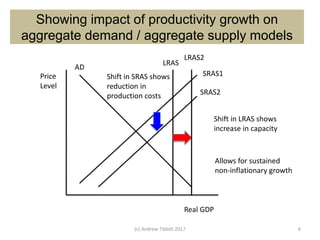

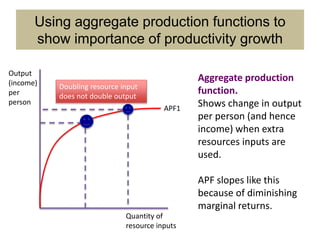

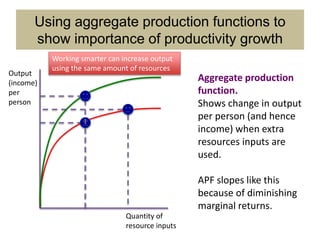

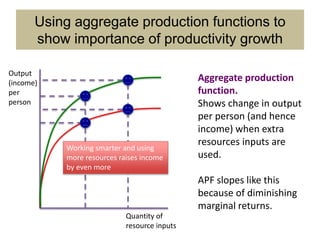

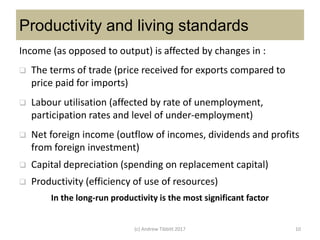

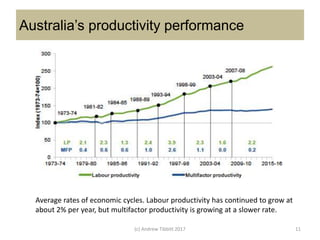

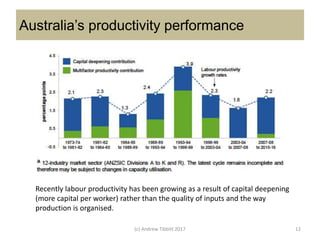

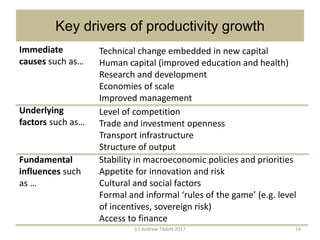

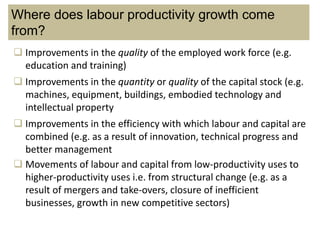

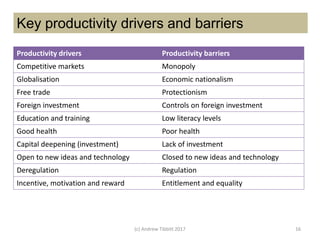

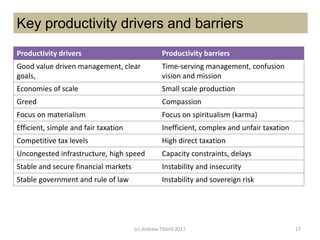

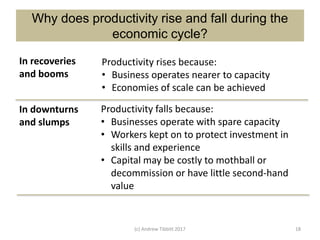

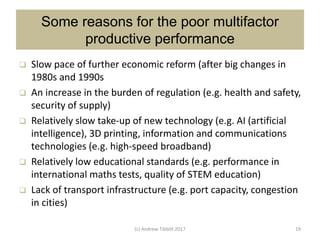

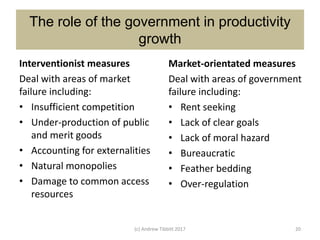

Productivity is measured as output per unit of input. It can be measured for individual businesses but is harder to measure for the whole economy. Productivity growth leads to economic growth, price stability, full employment, and more efficient use of resources. It allows countries to produce more goods and services from the same inputs. Sustained productivity growth depends on competitive markets, investment in infrastructure and education, innovation, and effective economic policies. Barriers include lack of reforms, over-regulation, and inadequate infrastructure.