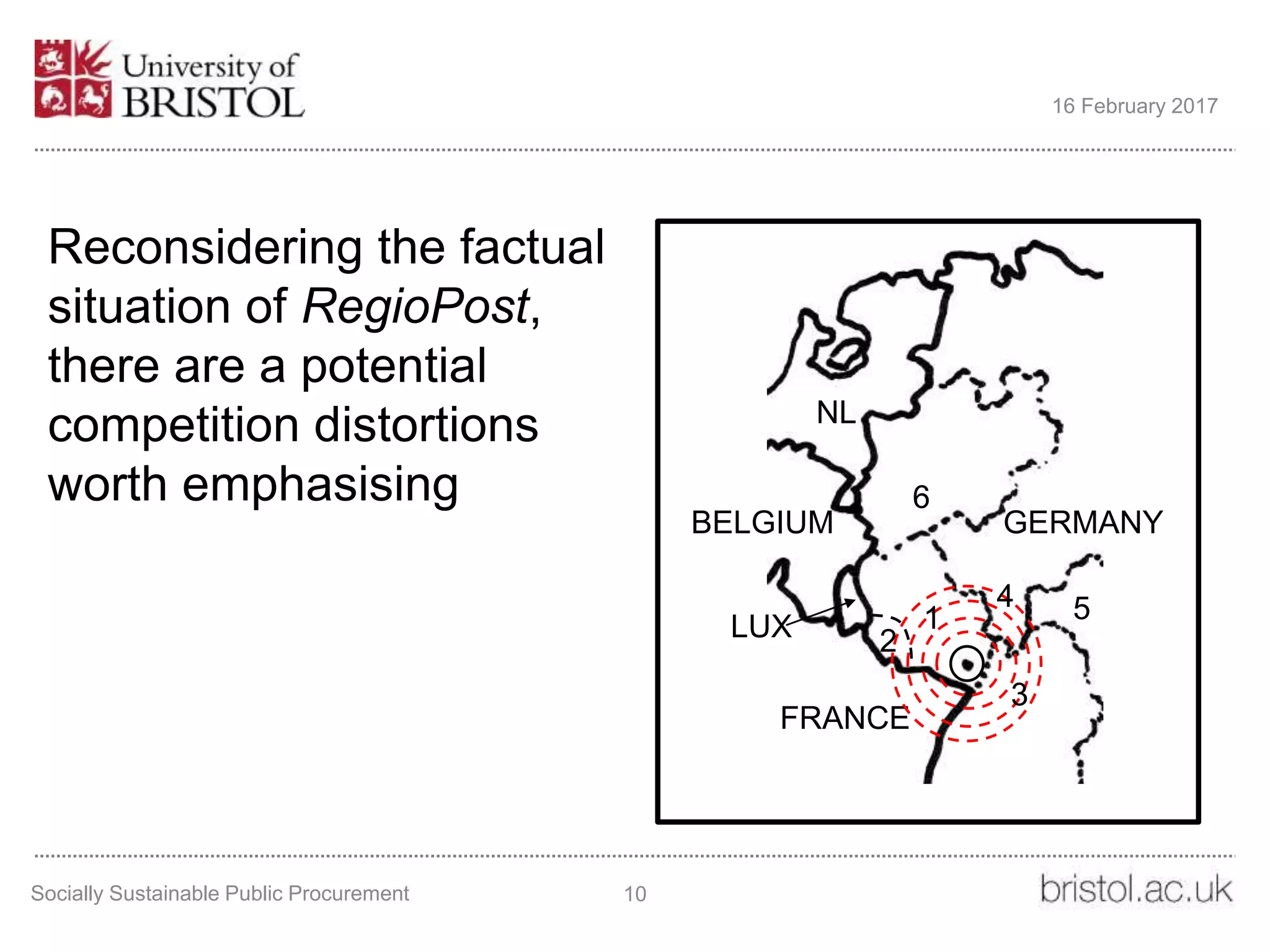

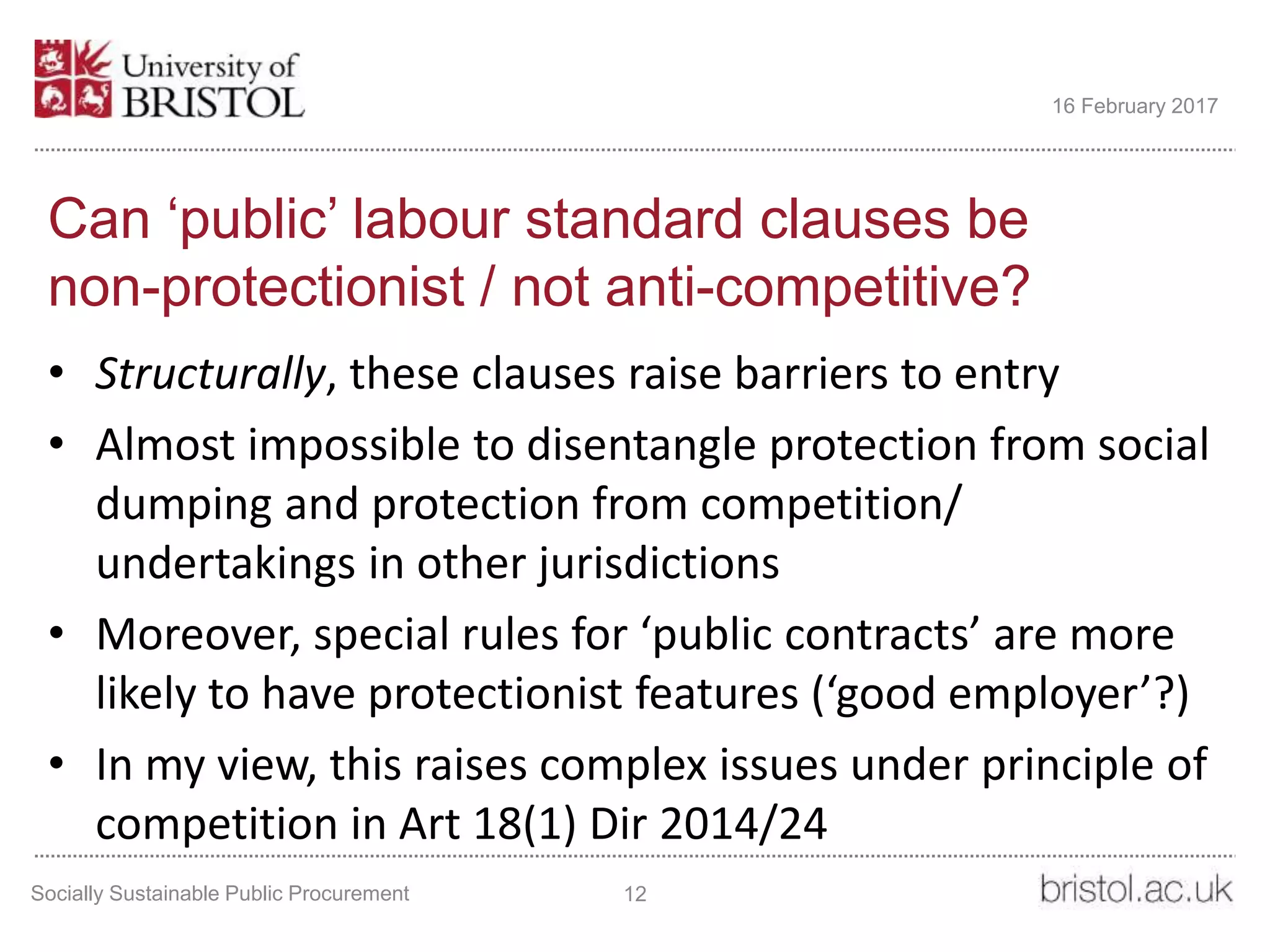

The document discusses the implications of socially sustainable public procurement on labor standards and competition law within the EU context. It highlights the limitations of enforcing minimum wages at the EU level and the challenges posed by varying regulations across member states for cross-border procurement. Additionally, it emphasizes the need for a strict proportionality test when applying labor standard clauses in public contracts to avoid structural competition restrictions.

![Limits to labour standards’ setting and

enforcement in EU economic law

• In simple terms, wages cannot be regulated at

EU level [Art 153(5) TFEU], but there has been

EU intervention as a result of the financial crisis

[see eg Schulten and Müller (2015)]

• Development of EU-wide minimum wage (policy)

faces significant constraints and limitations

Socially Sustainable Public Procurement 3

16 February 2017](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/procurementandlabourobjectivesleicsfeb2017-170213174333/75/Procurement-and-labour-objectives-some-thoughts-on-regulatory-substitution-and-competition-implications-3-2048.jpg)

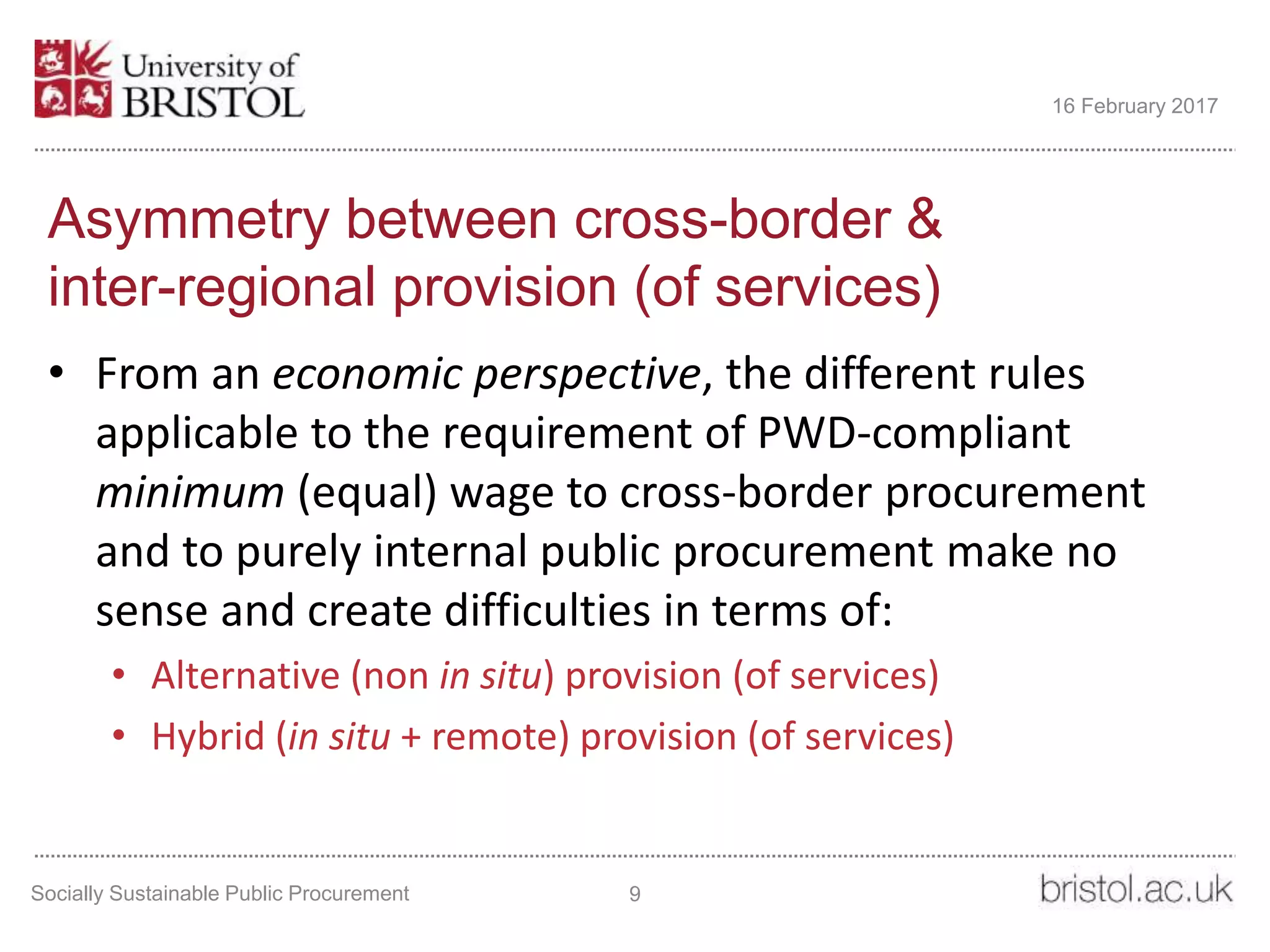

![Asymmetry between cross-border &

inter-regional provision (of services)

• Ultimately, this creates reverse discrimination of

domestic undertakings vis-à-vis intra-EU suppliers

• [and foreign ie non-EU suppliers, as a result of GPA?

—Art 25 Dir 2014/24; issue whether Bundesdruckerei and

RegioPost are considered part of Directive or not]

• This makes very poor economic sense [this

protectionism has severe potential impacts on public

sector efficiency] and is likely to trigger further litigation

Socially Sustainable Public Procurement 11

16 February 2017](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/procurementandlabourobjectivesleicsfeb2017-170213174333/75/Procurement-and-labour-objectives-some-thoughts-on-regulatory-substitution-and-competition-implications-11-2048.jpg)

![Labour standard [minimum wage or not]

clauses and Art 18(1) Dir 2014/24

• Art 18(1) Dir 2014/24 prevents any artificial narrowing

of competition

• Creation of ‘procurement specific’ labour standards / other

requirements seems to fit this analytical framework

• Difficulty of applying Art 18(1) in a RegioPost scenario

-> issue of mis-transposition of Dir 2014/24?

• Strict proportionality test to be applied to inclusion of

labour standard clauses [under Art 70 Dir 2014/24]

Socially Sustainable Public Procurement 13

16 February 2017](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/procurementandlabourobjectivesleicsfeb2017-170213174333/75/Procurement-and-labour-objectives-some-thoughts-on-regulatory-substitution-and-competition-implications-13-2048.jpg)