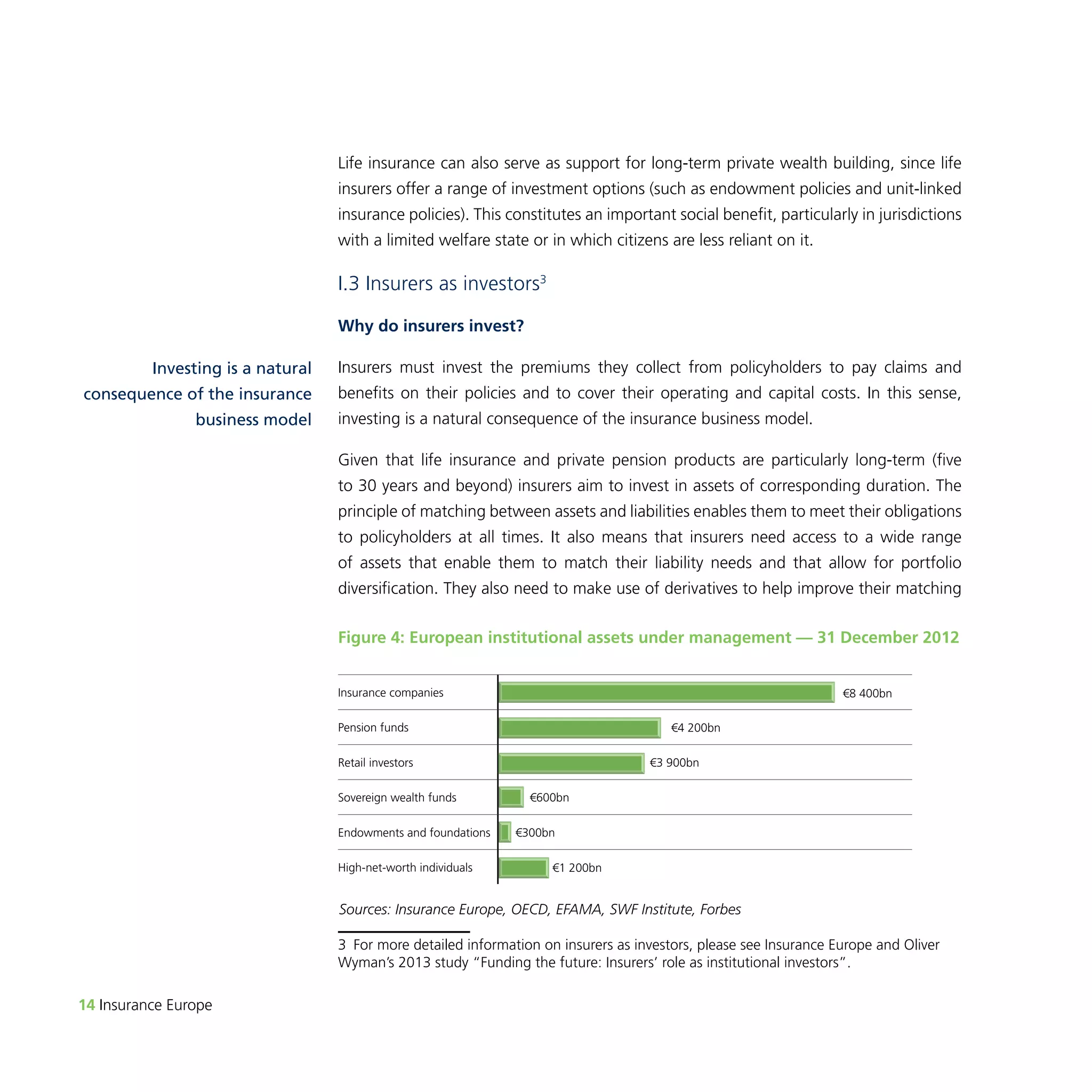

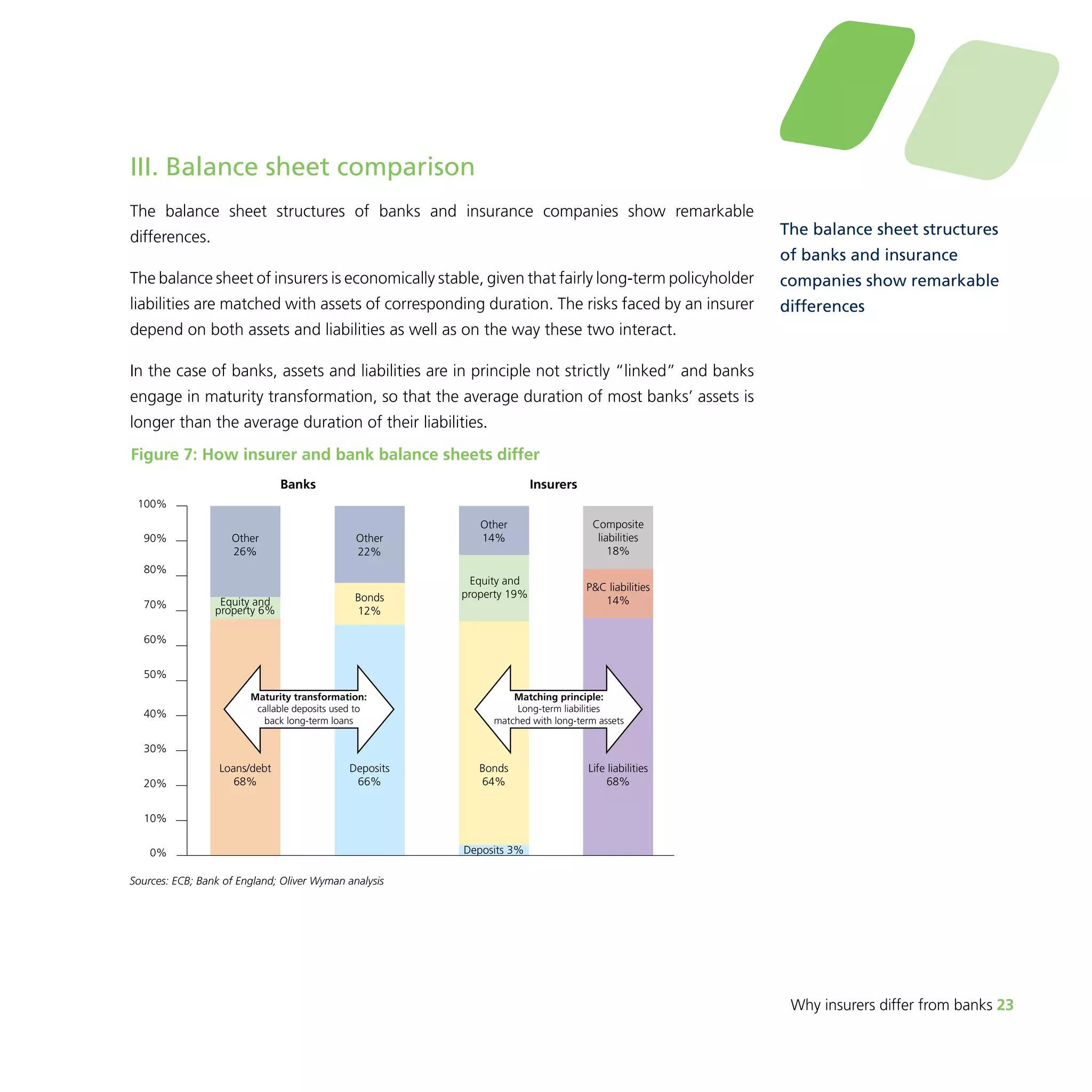

The document discusses the key differences between insurers and banks. It notes that insurers exist to take on risks from policyholders and pool them, while banks engage in deposit-taking and lending. The core activities, risk profiles, and balance sheets of insurers and banks differ significantly. Specifically, insurers face underwriting, market, and asset-liability mismatch risks, while banks primarily face credit, liquidity, and market risks. Applying banking regulations to insurers would fail to account for these fundamental differences and could negatively impact the insurance sector and economy.