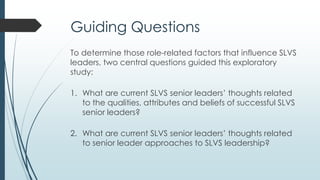

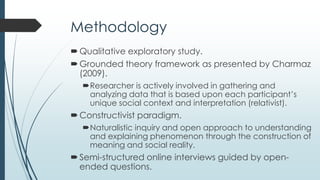

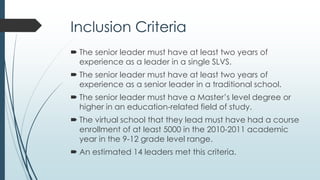

The exploratory study investigates the role of state-led virtual school (SLVS) leaders, highlighting the need for further research on their characteristics, leadership approaches, and the challenges they face. Findings indicate a reliance on prior experiences and informal knowledge, with an emphasis on student success and transformational leadership practices. The study suggests the development of comprehensive leadership training and certification programs to better prepare future SLVS leaders.